Santiago, Chile – Real-time network monitoring

Network controllers and operators must have continual access to quantitative and qualitative information to manage and maintain the road network as effectively as possible.

Network monitoring involves keeping track in real-time of traffic conditions and external events likely to affect the use of the roadway, such as adverse weather, traffic incidents and other events. It includes Quick response to incidents based on monitoring of road and traffic conditions enables the operator to take appropriate actions to minimise the negative effects of incidents. The resulting impacts of the operations activities are again monitored and evaluated to take further action. A closed loop of information involving monitoring, decision-making and evaluation of resulting impacts is thus maintained.

The main objectives of road network monitoring can be summarised as follows:

Each objective is realised through various solutions, including the application of ITS technolgies.

Network monitoring is expensive. When considering the provision of monitoring systems it is important to establish the key purpose of collecting specific information and to design systems accordingly. Depending on the local context, information may be needed on a variety of factors – such as traffic and weather conditions, incidents and other road and highway status alerts – in order to provide intelligence for network operations activities, traffic control and information systems. Other examples are:

Managing events on the road network in real-time requires the means to detect and rapidly assess any situation that is potentially problematic as soon as it arises, with reliable procedures for a quick and suitable response.

To carry out these tasks, the desk operators must:

Analysis of the situation must have regard to:

This task demands major efforts to develop systems that capitalise on and disseminate past experience. Crucially it requires good staff coordination to avoid instances where staff work at cross-purposes during an emergency.

All the organisations and agencies that have a part to play in the network operation will have an interest in network monitoring activities. In planning, designing and allocating resources to the network monitoring system the equipment, information systems and operational procedures need to be specified in line with the coordination arrangements. In particular, when multiple partners are involved at the operations centre a flow of command needs to be established in order to ensure smooth implementation. (See Operating Agreements)

Agreement on operational procedures is especially important when the data being monitored are used for enforcement purposes. Usually, network operators do not have the power to actually catch or rectify the offending situation even when it is necessary to do so in order to ensure a smooth operation. Close planning and cooperation with enforcement agencies are critical. (See Enforcement)

The core data used to assess and manage the roadway is collected and collated by manual methods and automatically for use in both real time and non-real time applications. Choice of equipment and methods is dictated by the required services as well as the available human and financial resources. (See Methods & Procedures and Vehicles & Roadways)

Example data includes:

Care must be taken not to overload operators and systems with data and information without sufficient filtering or analysis. The following questions must always be addressed:

Certain constraints must be considered. The organisation will need to

ITS-related monitoring systems are characterised by the use of electronic sensors, data processing by a central computer, and data transmission. The system requirements are heavily dependent on the operational activities that it will support (operating, controlling and providing services) and the road network characteristics under consideration. (See Information & Data Gathering)

When an existing (legacy) system needs to be incorporated in the new monitoring system, it is important to evaluate the system applicability for continued use and whether it can satisfactorily accommodate new requirements.

Privacy is a critical issue when incorporating detection technologies that can identify individual vehicles. Typical technologies for these include CCTV, video image processing, automatic vehicle identification (AVI) and cell-phone tracking. It is therefore important to agree a policy of how to respect privacy at all stages: when information is collected, when it is being used and when it is exchanged and transmitted between relevant organisations, including making it available to the public. (See Privacy)

Automated incident detection is most commonly found in urban areas where traffic congestion during peak hour periods is experienced. However, initiatives such as e-Call (Europe) are developing integrated emergency response infrastructure, which will improve detection and response to incidents in all areas (rural and urban) by means of global positioning, in-vehicle sensors and satellite and cell phone technology. In-vehicle systems where on-board electronics improve the driver’s competence in congested travel conditions, at night or in bad weather, can also reduce the occurrence of incidents. (See Automatic Incident Detection)

In the case of automatic detection, the reliability of the monitoring system needs to be evaluated after installation, with respect to the detection function, the telecommunications function, the data processing function and the overall system function. Typical evaluation points include accuracy of measurement, timeliness of data transmission and processing, ability to provide required data, reliability of software algorithms, system resilience under required environmental conditions and maintenance costs.

In the case of non-automatic detection such as phone calls from users, the reliability and accuracy of the data also becomes an important issue. Another issue is the problem of operators receiving too many calls with redundant information. This often happens in the case of large accidents that many people can clearly observe.

Information from road users can be gathered directly by the traffic or operations centre or through a dedicated call centre. In both cases it is very important to handle the gathered information quickly and to confirm its value through the use of the other information sources (such as loops, cameras, mobile patrols). Information from drivers can also be a complementary input for the traffic centre database and is an important tool where monitoring equipment is limited.

User feedback concerning the efficiency of the roadway and traffic conditions is a useful input for determining the perception of the network monitoring operation. This can be achieved through:

Detection systems can enable information to be given to the network operator regarding the onset (or probability of onset) of difficult weather conditions (fog, black ice, snowfall, cyclones, dust-storms) or other unfavourable natural events (landslides, floods). The network operator's task is to respond by issuing appropriate advice on road use through all available channels. (See Traveller Services)

This requires systems for the collection, processing and centralisation of counts and information, organised relations with the safety and emergency call-out services or the assistance services, automatic or non-automatic warning systems (emergency call network, automatic incident detection), and the organisation of regular patrols on the most sensitive roads. (See Data Aggregation and Analysis)

Real-time data accumulation to serve as historical data is an important task of the monitoring mission. It can be used in such a way as to compare real-time data with historical data and find out the presence of incidents on the network. Before/after study of operations and control functions also depends on comparison of these data. In addition, historical data can provide important information to the ITS-unrelated programs of network improvement such as geometric improvement and pavement rehabilitation. (See Data Management and Archiving and Data Ownership and Sharing)

Information is provided here on a number of methods that are widely used in network monitoring at all levels of operation.

The responsibilities of patrol officers are to:

To carry out this task the patrol officer monitors the assigned network segment, reports and responds to minor incidents where appropriate. Patrols are developed only if an Operations Centre is capable of undertaking actions proposed by the patrol reports.

Patrol operating procedures, schedules and routes will depend on the department’s objectives and operating strategy, and they must be adjusted to meet actual needs (scope and frequency of problems) and resources available.

Patrols may be conducted in various patterns:

Patrol officers must carry, in their vehicle, a procedures manual, automatic response sheets, a logbook, a communications device (radio, telephone), and possibly response equipment.

Patrol officer training must include an introduction to specific reporting procedures and the submission of reports in a standardised format (For example: I am arriving on the site / I am leaving the site, traffic is reduced to one vehicle approximately every five seconds, the traffic jam is at least 600 m long and growing). (See Mobile Service Patrols)

Aerial observation missions provide the opportunity to complement raw data with an analysis and potential solutions together with real-time observations of driver behaviour and the effectiveness of response actions. Nevertheless aerial observations are expensive and are viable only for exceptional events and heavily trafficked areas that routinely experience a high frequency of disruptive incidents.

The duty desk essentially involves:

The specific resources for the duty desk include:

This task requires an intense effort in terms of organisation and communication both internally and externally but it also contributes to improving the department’s efficiency as much from the perspective of users as of partners.

Calls may be recorded in a format that includes:

The decisions made and actions taken must also be noted, including the date and time.

A log must be kept in real time and the information logged must be complete. The usefulness of a log is directly dependent on the experience and qualifications of the officer who writes it. In major events, a person must be assigned exclusively to this task.

Each participant in the operation of the road system must keep a log of their assigned tasks: after-hours duty officers, patrol officers, winter maintenance services, operating control centres, etc. The log may be kept in a notebook or electronically on a computer.

Since records may be used in legal proceedings, the log must be impossible to falsify (non-removable numbered pages or secure electronic copy).

Maintaining comprehensive logs (record everything in real time, as events unfold, with no possibility of changing entries after they are made) ensures:

To do this, the network operations department needs the ability to provide well-informed solutions based on expert analysis of traffic volumes, traffic distribution and the evolution of traffic trends. It must collate and validate data for future operational planning and for the provision of valuable traffic statistics.

The data required for traffic studies differs according to the problem to be addressed, for example:

Interpretation of counts often requires consideration of other factors such as weather data, incidents, accidents, major events. It is therefore necessary to relate the collated traffic data to records and observations summarising the day’s events.

Conducting traffic count studies requires high-performance counting equipment, and computers to process the date including:

The complexity of data management, count evaluation and simulation tools, requires basic training in traffic engineering and in statistics to ensure credible, relevant results.

The programme proceeds as follows:

The programme requires:

There is always the risk of an unexpected event (such as adverse weather, major disruptions on a neighbouring arterial) occurring at the last minute, making established forecasts totally irrelevant. Furthermore, some preventive operating measures may prove inadequate. However, regular attention to near-term and future traffic forecasts will reduce the likelihood and frequency of an emergency response being needed.

ITS technologies perform a key function in gathering prevailing road network information and providing support for other network operation activities. The basis of ITS-based network monitoring is traffic monitoring and detection (such as vehicle detection devices, probe vehicles, sensors and CCTV cameras) and the interpretation and presentation of information on the state of the road network.

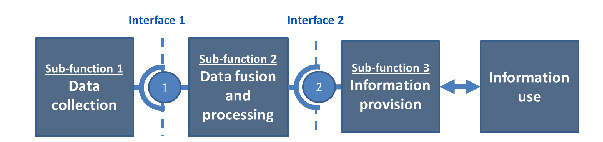

A prerequisite for many ITS services, including traffic and incident management is the collection of timely, accurate and reliable information about traffic flow and road conditions. (See Operational Activities) These ITS services can be thought of as part of an information chain that includes:

Network monitoring systems and ITS technologies play a central role in assessing transport network performance in real-time, predicting the most likely state of the network, validating capacity enhancements and supporting long-term planning. The primary applications that enable road network monitoring are:

Operationally the primary organisational structures and functions – necessary to provide a road network monitoring service – may include:

One of one of the most common road network monitoring technologies is CCTV which has been developed to support Traffic and Control Centre (TCC) operations (also known as Traffic Management Centres - TMC). There is a range of other complementary and additional sources such as fixed detectors and the data collected from mobile devices. (See ITS Technologies) The use of vehicles as measurement ‘probes’ is growing, in addition to traditional use of static roadside detectors. (See Probe Vehicle Measurements and Roadway Sensor) Together, these sources can provide reliable, cost effective and accurate journey-time information for the whole road network.

It is always necessary to be confident that the data is accurate and reliable. For example, a realistic representation of traffic conditions needs to take account of fundamental differences between detector types and other sources - that influence how data from each type of detector should be interpreted. To build a complete picture it is likely that data from different types of detectors will need to be combined before it can be interpreted to provide usable information on network status, a process known as ‘data aggregation and fusion’. Such information is basic to the operations of a Traffic Control Centre (TCC), and is often needed in real-time, especially for a complex or congested road network. (See Operational Activities) None of this would be possible without a variety of communication technologies and technical standards to ensure the timely use of traffic data. (See ITS Standards)

Road network monitoring is a strategic function that enables effective road network operations and incident management. The purpose of network monitoring is to secure accurate, reliable and up-to-date information about road and traffic conditions across the network. A number of activities are required to achieve this:

Traditionally, roads and highways were owned and managed by public bodies as an asset. In the past these bodies were responsible for deploying traffic detectors, filtering and combining their outputs, making them available for traffic management purposes and for displaying messages on Variable Message Signs (VMS). Many road authorities still do this, but in recent years several trends have contributed toward new organisational structures for network monitoring, including:

Private sector service providers have a growing role. Innovations in mobile social networks and mobile phone-based navigation services mean that the users of traffic information may also act as a source of traffic data, otherwise known as ‘crowd-sourced’ data. (See Data and Communications) In future, this may complement conventional point-based vehicle detectors in regions that cross-administrative boundaries, on roads where detectors do not exist, or even on roads where detectors do exist. These new data services (See Future Trends) can assist and complement public highway agencies.

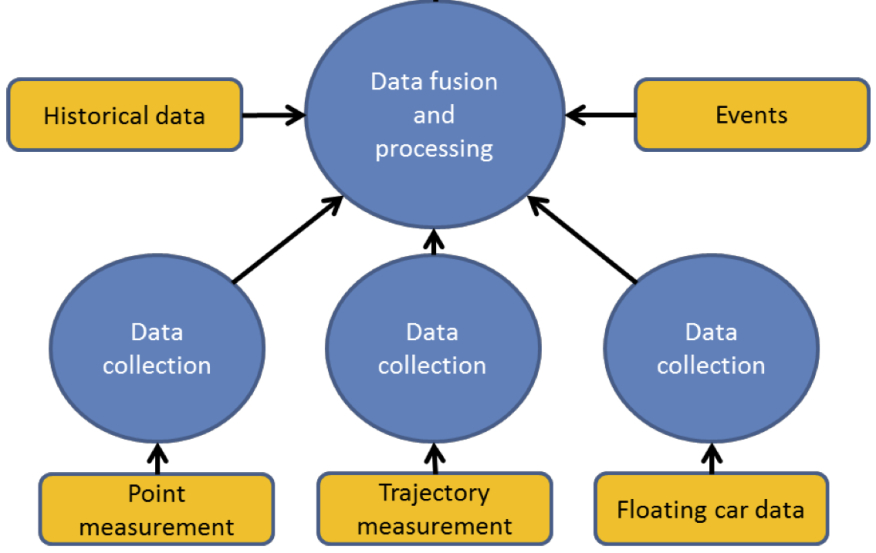

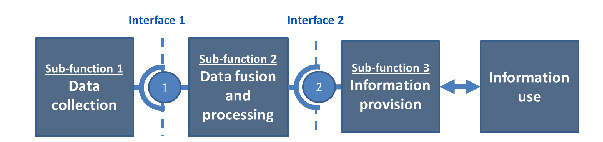

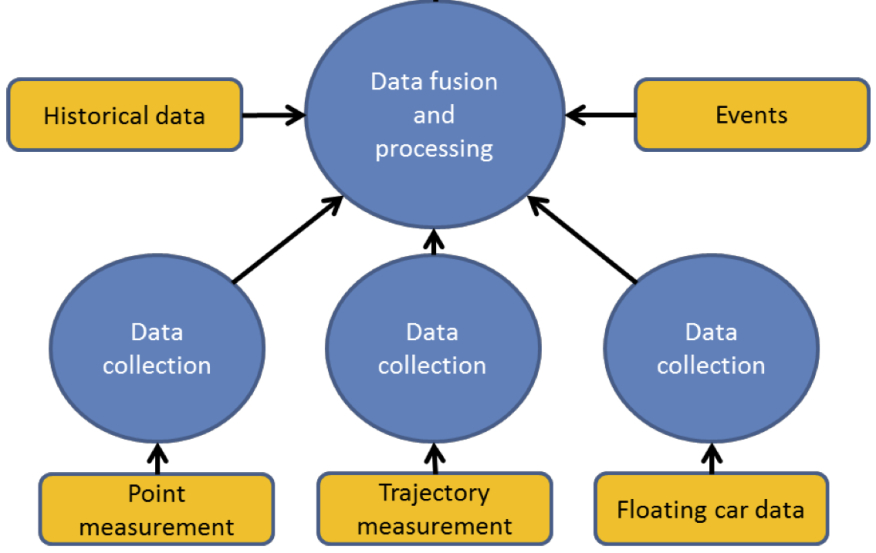

The typical functional architecture of an ITS service that monitors traffic conditions and travel times is shown in ‘The Information Chain’ in the figure below. (See Data and Information)

The Information Chain. Reproduced by permission of the Easyway Consortium (http://www.easyway-its.eu.) a trans-European project co-financed by the European Commission.

The ITS architecture for the information chain comprises three parts:

Sub-function 1 – the devices and applications for the collection of traffic data (in addition to weather and journey-time monitoring) from:

Sub-function 2 – the processing that combines real time data with any traffic prediction and journey time information that may be derived from the sensor data collected. (See Data Aggregation and Analysis)

Sub-function 3 – the selection, organisation and presentation of information (derived from sub-functions 1 and 2) to the Traffic Control Centre (TCC) operator.

The main application area for network monitoring are:

Predictive and real-time information about traffic conditions and travel times contributes strongly to the improvement of traffic efficiency. It enables road operators to understand how well the road network is operating, and enables the timely detection of incidents. For example, a TCC may wish to measure the performance of its road network to provide tangible evidence that the methods to reduce congestion and improve the consistency of journey times are having a positive effect. Visualisation of the state of the road network at the TCC, interpreted from a network of static and mobile detectors, is critical. (See Traffic & Network Status Monitoring)

Traffic and network status monitoring activity involves:

Effective traffic and road network status monitoring depends on a combination of static detectors, Closed Circuit Television Cameras (CCTV) and ad-hoc reports of unplanned incidents. Ad-hoc sources include the police, road authorities, vehicle breakdown organisations and public transport operators. (See Other Monitoring Sources) The TCC will use the data to monitor traffic, manage incidents and monitor weather and road surface conditions. (See Operational Activities and ITS & Road Safety)

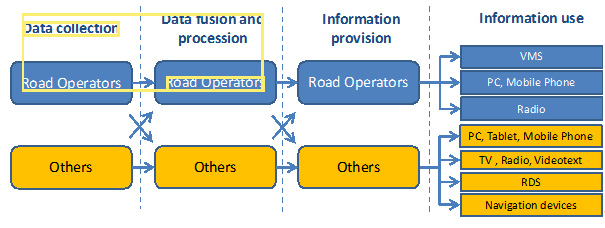

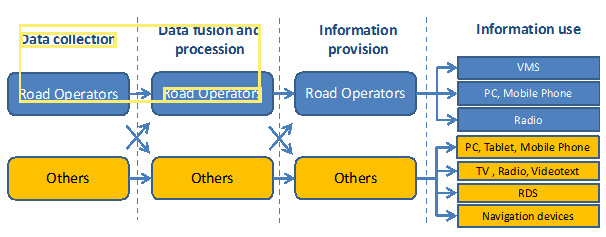

CCTV cameras have traditionally been a source of real-time traffic information and the means for Traffic Control Centre (TCC) operators to validate reported incidents. The operator also needs to be presented with a general view of the road network which draws attention to information relevant to the operator’s task. This could include traffic flow, occupancy, queue length, equipment status and messages that are presented to road users by Highway Advisory Radio (HAR) and Variable Message Signs (VMS). The public sector or third parties are generally responsible for data collection and its aggregation – whilst users of the information will include the TCC operators, other stakeholders and the general public - as shown in the figure below.

Organisational Model and the relationship with other parties. Reproduced by permission of the Easyway Consortium (http://www.easyway-its.eu) a trans-European project co-financed by the European Commission.

The same combination of technologies (hardware, software and computer graphics) will also provide the means to configure and update traffic plans and manage voice communications with the TCC (such as telephone call set-up and recording), reporting, organisational performance management and operator training. (See Operational Activities)

Many technologies provide the basis for systems to monitor traffic levels and determine the real-time performance of a road network. (See Vehicle Detection and Probe Vehicle Measurement) The systems aggregate the data and make them available to the TCC operators and for Automatic Incident Detection (AID) systems. (See Automatic Incident Detection (AID)) Typically the components required for a highly reliable, fault-tolerant and flexible system architecture at the TCC - for the purposes of information collection, storage and presentation - may be split into four categories:

System Status Wall Display and operator workstation, Florida District 4

Wall Display, Costanera Norte, Santiago de Chile

The TCC will also be equipped with telephone (conventional circuit-switched or Voice over Internet Protocol) and a Private Mobile Radio (PMR) system.

The key to successful traffic operations is inter-agency cooperation and coordination – for example between the TCC and other stakeholders such as the emergency services, major vehicle fleet operators, ports, airports and rail stations. (See Interagency Working).The extent of inter-agency cooperation has a major impact on the TCC’s operations and the support systems required. Integration can be facilitated by co-locating stakeholders in the TCC – as happened during the London Olympic Games.

When a new TCC is being planned or an existing TCC is being upgraded – it is important that the TCC system architecture (including the collection of traffic data) is aligned with the requirements of core applications. This is– usually split between highway management and arterial route management. These are often the responsibilities of different agencies but in future more integrated solutions may become available. (See Regional networks)

The system architecture should be designed to enable more efficient TCC operations at lower cost. For example, as the complexity of the network monitoring infrastructure expands, the architecture should provide for greater use of automated system health monitoring. This ensures that the TCC and field equipment are performing their expected functions properly. (See What is ITS Architecture?)

The use of proprietary interfaces for vehicle detection and traffic monitoring systems can increase the cost of expansion and increase the dependency on a small number of technology vendors and system integrators. Requiring standards-compliant interfaces can help retain supplier independence for the road operator – providing the requirement generates a market response. (See ITS Standards)

Any changes to a system needed to accommodate technology innovations is likely to impact on maintenance and operator workflow - requiring training, a revision to documented procedures and potentially – opportunities for innovation. For example, the use of a Knowledge-based Expert System (KBEST) to provide recommendations to TCC operators on traffic plans, is an innovation that can improve the efficiency of staff having to monitor several routes simultaneously. (See Future Trends)

CCTV cameras can help monitor traffic conditions, detect incidents, validate them, monitor the emergency services and help manage incident clearance. In some applications, 80% of incidents are detected with CCTV cameras – although their performance is compromised at night on routes without artificial lighting. CCTV cameras can be subject to vandalism and their communication cables subject to theft, even if optical fibre cables are used. TCC operators may wish to transfer some of the upgrade and operating risks to third parties (see box on Design, Build, Operate and Maintain - below). The involvement of third parties in data collection and data analysis (on an availability payments basis) can replace the need for expensive investment in additional network monitoring infrastructure.

Design, Build, Operate and Maintain

The South African National Roads Agency (SANRAL) awarded a Design Build Operate and Maintain (DBOM) contract to a single contractor who was responsible for the refurbishment and upgrading of regional TMCs. This included the addition of new traffic monitoring infrastructure, its maintenance, operations and coordination with communication service providers and emergency service providers (Case Study - ITS Design & Operating Services, South African National Roads Agency (SANRAL) (South Africa)).

Pressure on TCCs is higher than ever before in the face of:

Traditionally, vehicle detection and traffic monitoring systems lacked the capability to perform data error correction, data analysis, self-diagnostics and reporting. As the capability of these systems has improved, more data needs to be exchanged with the TCC – and health monitoring may be centralised at the TCC.

In practice, each function of a TCC relating to network monitoring can be upgraded separately. This can be facilitated by dividing the TCC into functional modules and developing upgrade requirements for each:

Weather monitoring is focused on the impact of weather on driving conditions and the operational measures needed to minimise travel disruption. The accuracy and timely delivery of weather information and weather warnings contributes to informed road users, an increase in road safety (by reducing the probability of an incident), and reduced operational costs of commercial vehicles, snow and ice clearing.

Weather monitoring is the measurement, communication and interpretation of weather information from multiple sources. The TCC’s weather monitoring function is focused on monitoring the condition of road surfaces, driving visibility and the use of infrastructure-specific information relating to the road network - such as bridges (which can be closed due to high wind conditions) and tunnels (that may be liable to flooding).

Current and predicted weather conditions on a road are critical to users planning a journey or already travelling on the road. The intention of a weather monitoring service is to encourage different user groups to adapt their travel plans (route, mode, timing) or change driver behaviour (speed) - to avoid the negative impacts associated with weather conditions. To make informed choices, travellers need to be aware of the likely weather along their route.

The benefits of timely and accurate delivery of weather information and weather warnings include:

Weather Monitoring and Warning Systems

The Finnish Transport Agency operates a national route monitoring service that reports on driving conditions from mid-September to mid-May. Highways England provides an on-line search tool for the latest traffic reports presented on a road-by-road basis, that allows user to search for weather-related warnings – See http://www.highways.gov.uk/traffic-information/

Regional and route-based weather stations are the most common static measurement systems – although the weather monitoring function must also have the capacity to accept ad-hoc reports from other organisations. This will include the police, other transport service providers, a national meteorological centre and members of the public. Roadside measurement stations are most commonly used for localised weather monitoring – such as the one shown below.

Route-based weather data measurement, Virginia (USA)

Traditionally road users have had to actively request information before undertaking a journey. The recent introduction of improved digital radio broadcasting methods now mean that road users can subscribe to services providing regional or route-based messages and other weather alerts during their journey. Examples are Radio Data System-Traffic Message Channel (RDS-TMC), radio break-in services, instant messaging technologies such as the Short Messaging Service, Twitter and Sina Weibo – and roadside Variable Message Signs (VMS). This trend from users requesting information (‘pull’) to users being informed (‘push’) increases road users’ knowledge of weather conditions along their journey. (See En-route Information) Services providing traffic-related messaging announcements are widely used in Australia, Brazil, Czech Republic, Italy, South Africa, Sweden and other countries.

Advances in computer-based ‘expert systems’ are improving the accuracy of predictions by taking into account historic information and trends. The technology continues to develop quickly - such as the piloting of specialised GPS-based measurement stations in the USA to detect atmospheric variations (such as rainfall) based on the measurement of the travel time of signals from satellites. Complementary technologies include wireless communications (from roadside stations for example) and sophisticated back office computational resources.

The data aggregation processes should provide dynamic weather information for specific roads, road segments, routes or administrative areas - updated at defined intervals such as every 5, 15 or 60 minutes depending on how quickly the weather conditions are changing. The information collected needs to be relevant to the target audience. It can be customised to assist those involved in road maintenance and infrastructure management or to provide travel information to road users.

Weather information that is broadcast to road users may include information on the condition of the road surface, particularly at exposed sections such as bridges that may be more prone to surface ice, high winds or rain. The most common dynamic information that is measured is:

Integrated monitoring stations combine traffic monitoring, emissions monitoring and weather conditions. These monitoring stations can be pre-set to report only if conditions exceed specified levels such as a reduction in temperature, road friction and grip - that may indicate the possibility of localised icing or perhaps a reduction in visibility.

Typically, traffic management staff are not responsible for interpreting the wide variety of data sources. Instead, external experts may be contracted to provide customised reports for the purposes of traffic management. These experts may be part of the national meteorological service or weather bureau.

Weather information may be gathered from data sources owned by others in the public or private sectors. Partnership agreements may be required to allow sharing of data between organisations and its interpretation – for example, in relation to:

The long-term development of a weather monitoring service needs to take into account any potential increase in the size of the geographical coverage, the use of standards and a common approach to reporting. To enable a common understanding by all travellers, a uniform presentation of weather-related signing and messages is recommended, to ensure a ‘common look and feel’.

Interoperability requirements may also apply – to ensure that sensor networks can be expanded without significant modification and to make it easier for other parties to provide customised weather reports to traffic authorities. Data standards may be used to enable the transfer of weather data between back offices - although it is likely that these standards will be needed anyway to improve communication between TCCs or with other government agencies. Examples of these ‘centre-to-centre’ standards include DATEX II (Data Exchange) which is the most common in Europe and NTCIP which is the most common in the USA. The Transport Department of China maintains a comparable library of standards.

The high cost of establishing comprehensive weather monitoring and early warning systems for extreme weather can be a barrier to many countries wishing to protect their national road network. This may have a critical impact on inter-regional trade and urban infrastructure such as roads and drainage systems.

Regional Associations of the World Meteorological Organisation (WMO) provide a valuable resource for sharing best practice of weather monitoring and multi-hazard warning systems between regions. It helps provide access to sources of regional weather reports and promotes methods of risk management and climate change adaptation.

Weather monitoring stations should be compact, easy to install, have low ownership costs (purchase, maintenance and upgrade) and operate on a long-term basis, without interruption, in regions that are most likely to suffer for weather-related conditions. Investments in early warning systems can also reduce the potential cost of a disaster response and ensure faster deployment of emergency services.

Subcontracting parts of the monitoring system to private sector contractors - to provide and maintain a network of weather stations and lightning discharge measurement systems - may provide a pragmatic solution to developing weather measurement networks without the public sector having to be responsible for their ownership.

Keeping track of vehicle journey times involves the measurement, interpretation and communication of vehicle detector data from multiple sources. Monitoring of journey times provides information necessary to determine the operational status of the network and level of service available to road users. (See Measuring Performance)

It is important to build user confidence on the reliability of journey time predictions. In some instances data may not be delivered in a timely manner or may be incomplete or inaccurate. The accurate and timely delivery of journey time information contributes to:

The purpose of journey time monitoring varies and depends on the objectives of the end user. For example:

Whilst journey time information is easy to understand, it is complex to calculate. Typically, a sensor network may include one or more types of detectors – each having different levels of accuracy, reporting rate, availability and reliability. Different methodologies and traffic models exist to aggregate real-time data, predict traffic conditions and calculate travel time information for the benefit of TCC managers and road users.

Trajectory measurement (tracking vehicle paths through a network from one point to another) and probe vehicles may be used to determine the travel time on road sections using various vehicle identification technologies. Examples are, toll tags and cameras that read a Vehicle Registration Mark (VRM).

The growth in the use of satellite navigation systems that can (with the consent of a user) provide speed and location information to third party service providers – adds to the level of detail of traffic information that may be provided to TCC staff and road users.

Complex and dense road networks provide greater challenges to measure and interpret data since each road segment is more closely interrelated with others compared to interurban roads. Combining data from different sources may be used to determine the operating status of a road network. The data collected must be reliable and the calculation algorithms must be accurate since end users will expect consistency between their experience on the journey and the information provided to them during the journey.

Many technologies provide the basis for systems that:

A single static measurement point cannot provide travel time information and a detector network that is intended for simple detection and vehicle counting may not provide a suitable starting point for reliable journey time measurement. Additional information on vehicle speed and progress on the road network is needed:

The most reliable journey time calculations use historical information and spot speed measurements to improve estimates, particularly in dense urban environments with complex road networks, such as Hong Kong.(See Vehicle Detection, Probe Vehicle Measurement and Network Monitoring Application Areas)

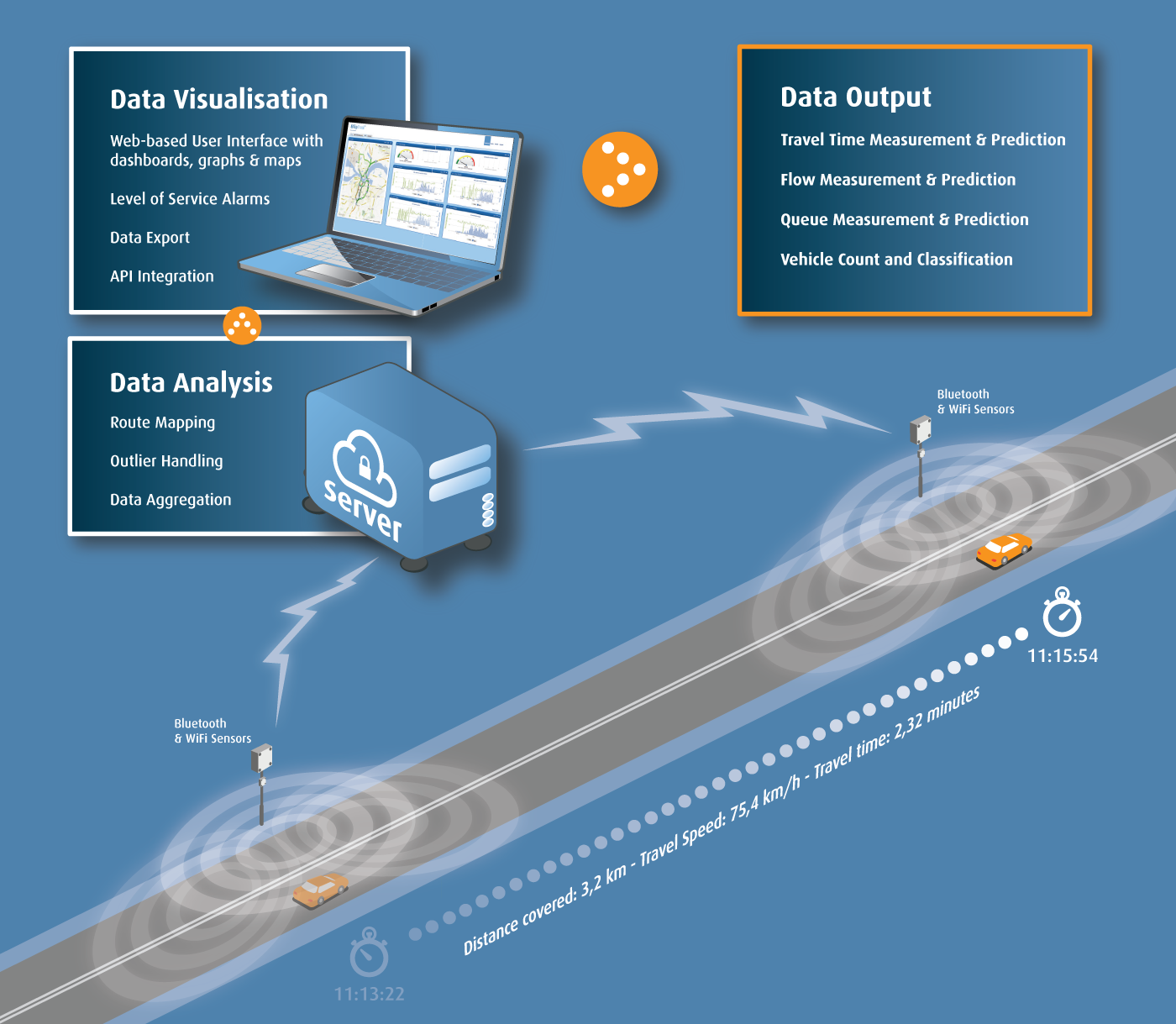

A combination of probe vehicle data and spot speed measurement can be used for journey time measurements. For example, capturing the identification signal from a small proportion of devices equipped with Bluetooth (in mobile phones and in-car audio systems) at different locations on the same link – enables the average speed on the link to be calculated as illustrated in the diagram below. This is done by dividing the distance between the detectors by the travel time measured over this distance. Alternatively Automatic Number Plate Recognition (ANPR) or Radio Frequency Identification (RFID) readers can be used to provide similar data.

Journey time measurement on a road section

Combining real-time measurements of link speed with real-time measurement of spot speed and historical data from related links - enables journey times between measured points to be calculated and presented as reliable predictions to road users in real-time – and can be displayed using colour graphics, as in the photograph below.

Speed Map Panel System (SMPS) on Route 3 at Yuen Long, Hong Kong

Average speed enforcement requires an accurate detection of the presence of identified vehicles at two locations separated by a known, precisely determined separation. This is illustrated below. Increasing the number of measuring points will increase the probability that the same vehicle (or in-vehicle device) will be seen elsewhere on the road network. If the measured speed is higher than a predetermined level (with an allowance for potential errors) the images captured are evidential-quality images and can be used to prosecute vehicle owners.

Average (point-to-point) speed cameras used on motorways

When deciding whether to invest in the infrastructure for journey time monitoring, issues to consider include:

Journey times may help identify incidents by comparing calculated values with historical information to allow prompt action to be taken. When designing the algorithms the effect of roadworks, unplanned incidents or planned events needs to be taken into account. This often requires local expertise on likely traffic behaviour.

Traditionally static roadside detectors have been used for journey time measurement. As the quality and capability of mobile phones develops, there is an opportunity to use their location-based data capabilities to measure link speed without the cost of deploying and maintaining static detectors, drawing on:

Where market penetration by mobile phones is low, or where there are low levels of traffic – static roadside journey time detectors will be needed. Manual monitoring of road links can provide real-time information on road network performance – but this method cannot reliably determine journey times without being supplemented by other measurements or by adopting a small proportion of probe vehicles (such as long-distance coaches).

Road network monitoring technologies are there to enable effective operations, incident detection and traffic management. Without a real-time view of the road network – gathered from sensors or other data sources – road operators would not be able to detect incidents, optimise traffic plans, inform the development of long-term upgrade and new capacity plans, or confirm the effectiveness of investments made.

The most cost effective data gathering strategies use existing detectors, sensors and other trusted sources. Most of the time, routine monitoring of static detectors provides the main source of traffic data but if an incident is detected other sources may become more important. For example, voice reports from a police officer at the scene of an accident can help optimise the most appropriate response. Other data sources that are used in network operations to influence traffic behaviour include weather monitoring stations (temperature, visibility and wind speed), ice alerts on bridges, and notifications of roadworks by utility companies or lane closures for road repairs.

Different vehicle and traffic monitoring applications provide different (but complementary) views of the road network. For example:

By combining different outputs, it becomes possible to automatically alert road operators to unusual patterns that could indicate that an incident has occurred. The figure below summarises the general data collection methods available.

Traffic condition and travel time monitoring. Reproduced by permission of Easyway (http://www.easyway-its.eu.) a trans-European project co-financed by the European Commission.

The key sources of data, the technologies for their collection and methodologies for their analysis include:

Vehicle detection is a critical enabler of traffic management, network monitoring and incident management. Examples are: the operation of signalised junction, variation in speed limits on managed motorway schemes, triggering red light cameras and controlling barriers,. In many cases, road users are unaware of vehicle detection systems but they do experience their effects. Vehicle detection is also an essential tool for incident management and traffic count surveys – and may complement reports from emergency services and other manual reporting sources.

Detectors may also be categorised according to where they are mounted:

Vehicles may be detected in a number of ways:

Vehicle detectors and sensors commonly used for traffic monitoring include:

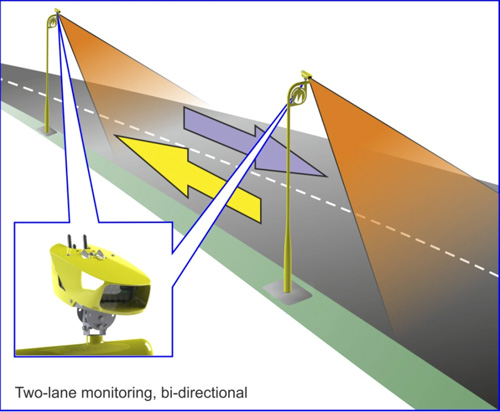

CCTV cameras are often used as a substitute for inductive loops in some applications and when interpreted by computer can provide valuable information to road operators about traffic flows, incidents, local weather conditions and the presence of pedestrians and animals. Images can also be used to derive information on speed, occupancy and traffic volume. It is also one of the main sensor technologies for Automatic Incident Detection (AID). (See Automatic Incident Detection) A typical CCTV-based detection scheme consists of cameras installed on masts, each having a roadside cabinet, located on the edge or the median of the road. The topography of the road network dictates where cameras should be located (and their height) - to ensure some overlap of coverage zones. Camera separation for AID is likely to be denser than for general surveillance.

Point sensors and cameras are used for incident detection and warning as well as for the daily management of the network:

There are advantages and disadvantages to using the different types of detectors:

In the urban environment, buried inductive loops are inexpensive but require on-going maintenance to ensure that a significant proportion remain operational. Above ground detectors may be more appropriate instead.

For remote locations, the cost of providing power and communications for detection equipment and CCTV cameras can be high, particularly if the security of the camera sites and communications cables cannot be ensured. In these circumstances, solar-powered sensors or cameras equipped with cellular radio modules can be used. Limited light (particularly in winter months) and variable radio coverage may mean that these installations are equally unreliable.

Cameras with overlapping coverage can increase the resilience of the camera network. When combined with Automatic Incident Detection (AID) and other sensors, a comprehensive view of the traffic network can be progressively developed. This can be expensive. (See Vehicle Detection and Probe Vehicle Measurement)

The data gathering process can capture information that, when used by itself or when combined with other data, would be regarded as ‘personal information’ in some countries’ legal frameworks, raising issues of data protection and privacy. (See Legal and Regulatory Issues)

The basis for traffic management and incident management is the monitoring of real-time traffic conditions by probe vehicles and other sources. The systems aspect of ITS is increasingly complex, combining hardware, software, and communications to provide transportation services (See Managing ITS Implementation).

Communications networks are critical to the timely gathering of data and its distribution between operational systems, their functional components and road users. The communications layer of a system architecture is concerned with the accurate and timely exchange of information between different system components that support transport solutions. (See What is ITS Architecture) Common to many of the resources and activities of a Traffic Control Centre (TCC) are:

To ensure that a TCC has a comprehensive and continuous view of the road network, the communications services must be reliable. This means that they must be available most of the time and have the capacity to meet the requirements of applications. Ideally each interface should comply with publicly available communication standards that are supported by a competitive network of suppliers - to ensure that the communication architecture can be expanded.

Data communications are needed for the transmission of voice, video camera images and other data from CCTV cameras, traffic detectors, weather stations, emergency phones and tunnel monitoring systems. Communications also play a central part in distributing data for the management of the highway. The most common forms are:

The communication architecture identifies devices, roadside controllers, intermediate communication hubs and equipment needed at TCCs. A well-designed architecture allows expansion - such as the addition of more CCTV cameras (including high definition cameras), detectors located on other roads and voice and other data services.

Careful management of the communication network and its security is needed to maintain the performance of the communication links and to protect investments in communication systems. The communication network will also need to support the distribution of advisory and mandatory instructions to road users, such as Variable Message Signs (fixed and mobile) and Highway Advisory Radio (HAR) or other control signals. The communication network specification must to be designed with this in mind.

An effective traffic management operation relies on effective communication between agencies. This is not always fully achieved due to differences in organisational responsibilities and the lack of open, non-proprietary communications protocols that are in use – often because available standards-based interfaces have not been adopted.

The sensor equipment (such as loops, CCTV cameras) and the applications they serve, will determine the communication requirements and may be restricted by limited bandwidth. Typically, the data is collected and uploaded to a central location. For instance:

Communications using Internet Protocol (IP) television and Voice Over IP (VoIP) systems and components support road network management based on multi-media services, and are becoming more common. Standards are necessary to enable interoperability across interfaces. Ideally, equipment installed on the roadside should comply with standards for ‘field-to-centre’ communications – such as those standards authored by the NTCIP (21xx, 22xx and 23xx), Directorate-General for Mobility and Transport (European Commission) (DATEX), ISO (TC204), CEN (TC278) and the Transport Department of China (JT/T-series standards).

CCTV cameras are a common means of monitoring traffic and keeping track of incidents. Digital CCTV with image processing software can also be used to measure traffic flows, classify vehicles and to detect, verify and manage incidents. For example, in some parts of South Africa they are used to detect 80-85% of all incidents occurring on main roads. As a means of monitoring a road network the value of CCTV is unparalleled because it provides control centre operators with visual confirmation of an incident.

In general, CCTV cameras are distinguished by having either analogue or Internet Protocol (IP) communication interfaces. IP cameras may suffer from image compression (such as MPEG-4) but offer more flexibility when designing and scaling a CCTV system. If high-resolution IP cameras are used, the communication network capacity must match the data output demand of each camera – and this is potentially as high as 4Mb/sec. Otherwise the cameras need to be specified to balance image quality with frame rate. Some cameras have the capability to be configured to reduce their image quality and image reporting frequency.

As the road network expands, so does the need to manage it better. Deployment and use of technologies and equipment that detect vehicles and capture other dynamic data can help. The capture, analysis and interpretation of this data lends itself to computer-based processing enabling the state of the network to be easily understood. The information that is produced by the data aggregation and analysis function is fundamental to managing road networks. (See Operational Activities)

The benefit of data aggregation and analysis increases with coverage of detectors - potentially extending into other regions that are the responsibility of other traffic authorities. Traffic management operations on travel corridors that include national roads, secondary routes and municipal routes, could benefit from traffic operators sharing sensor data, traffic reports and interpreted data.

There are many types of detector technologies which have different levels of accuracy, reliability, update rates and data content. The process of data aggregation and analysis provides filtering, error compensation, normalising and fusion with other data streams – to provide a picture of the status of a road link or the road network, which is useful for road management.

The purpose of data aggregation and analysis, otherwise known as Data Fusion is to estimate or predict traffic characteristics – such as current/future/mean vehicle speeds, vehicle classifications and their volume – as well as environmental information and other topics of interest to travellers.

A distributed network of detectors will provide a more accurate view of the state of the road network than is possible from information captured by a few detectors. Sophisticated analysis can:

Data aggregation and analysis relates to Sub-function 2 of the Functional Architecture of a service – as shown below. There are many different approaches to aggregating real-time data in order to predict traffic conditions and provide journey time information. In general they include data validation and certification. The result is a measure of the Level of Service (LoS) of the monitored route. (See Monitoring and Evaluation)

The Information Chain. Reproduced by permission of the EasyWay Consortium (http://www.easyway-its.eu) a trans-European project co-financed by the European Commission.

The most common traffic variables can be extracted by considering all types of detectors, fixed and mobile – and include:

Additional data may include historical traffic data, details of planned events, road closures and diversions.

Data aggregation and analysis depends on a network of measuring devices (static, mobile or a combination of both) and probe vehicle measurements. The process takes account of the characteristics of each type of detector to estimate the traffic state of the network.

Measured data may need to be pre-processed to correct for known errors, measurement bias and availability, and to update rates (data age) and coverage (small or large area). Typically, the methodologies used are:

It may be necessary to progressively refine the measured data and to include additional sources – in order to improve its accuracy and trust in the data. Generally this process involves:

Traffic condition and travel time monitoring. Reproduced by permission of the EasyWay consortium (http://www.easyway-its.eu.) a trans-European project co-financed by the European Commission.

The analysis of data collected from a distributed network of sensors can be extended beyond simple detection of vehicles to predict congestion, to refine the timings of signals in urban traffic control systems or to detect incidents. For example, a breakdown in the flow of traffic would be indicated by rapidly reduced flow rates and by an imbalance between detectors located before and after an incident.

The quality of traffic information based on a network of different sensor types and their configurations depends significantly on the quality of the data received from each measurement device or system.

Each measurement technology has its own characteristics, including its accuracy (how often its measurements are close to the truth) and its reliability and availability (the proportion of time that the device is working and able to provide data reliably):

the device might have an on-board internal clock – which may:

The data aggregation process may need to fill in missing data, adjust for time offsets, and eliminate the effect of known faulty readings. The objective is to derive an accurate understanding of prevailing traffic conditions. At the same time the process needs to be sensitive to anomalies that might suggest an incident. For example, a CCTV camera can compensate for the failure of another if the cameras are placed so their coverage of the road network overlaps. Similarly, measurements based on probe vehicles can complement static detectors and extend the measurement coverage of static detectors.

In many regions, CCTV has provided the main source of traffic data to operators. As the CCTV coverage increases, the use of Automatic Incident Detection (AID) becomes a valuable tool for traffic officers - as a specialised form of data analysis that extends the capability of manual operators.

The process of data capture may include information that, when used by itself or when combined with other data, would be regarded as ‘personal information’ in some countries’ legal frameworks - raising issues of data protection and privacy. (See Legal and Regulatory Issues)

Traffic patterns become more complex as a road network grows to meet demand or improve access. Higher levels of congestion on some parts of the road network mean that unplanned incidents can have an influence outside the immediate area of the incident. This can result in greater risk to human safety and economic loss. (See Traffic Incidents)

Automatic Incident Detection (AID) use computers to continuously monitor traffic conditions and detect incidents or traffic queues. Road networks equipped with a variety of detectors and CCTV cameras provide the basis for automated continuous monitoring. The detectors are deployed to provide speed, occupancy and flow data to assist with traffic operations. Their output can be used to alert control centre operators to unusual traffic conditions and to detect incidents much more quickly than by manual methods – and so manage them more effectively.

It has been estimated that for every minute saved in detecting incidents, verifying them, and clearing them – another five minutes are saved in recovery time. The use of AID can also improve road safety by enabling a more rapid response to the victims of accidents within the critical first hour, otherwise known by the emergency services as the ‘golden hour’.

Incident management involves the implementation of a systematic, planned and coordinated set of response actions and deployment of resources to prevent accidents in potentially dangerous situations and to handle incidents safely and quickly. They are a critical component of a decision support system for traffic operations on the urban and interurban road network and its infrastructure of bridges and tunnels. (See Incident Response Plans)

At the heart of Automatic Incident Detection (AID) are filters and algorithms programmed to scan and automatically recognise a variety of patterns. The operators can validate the incident using conventional methods such as CCTV cameras and information from other sources, such as reports by the police and emergency services at the scene of the incident.

AID systems use the available detector data and image streams from road sensors and CCTV cameras to continuously monitor traffic conditions for patterns that indicate that an incident may have occurred. When the system detects a potential incident, it can alert traffic operators to commence the Incident Management (IM) process and implement pre-programmed responses to warn drivers and others. AID provides an effective means of improving incident detection. It complements manual monitoring of a road network since it can detect incidents quickly (often within a few seconds) and is able to monitor more video streams than a manual operator.

The most common sources of primary data for AID are in-vehicle inductive loops and CCTV cameras although there are a large range of other technologies that may be used. (See Vehicle Detection) The equipment (sensors and CCTV cameras) is used for both incident detection and the daily management of the network.

AID depends on the interpretation of information (vehicle occupancy, speed and traffic volume) captured from the network of traffic detectors. The Incident Detection Algorithm (IDA), often used in combination with AID, should be responsive and accurate - with a low error rate - to ensure that the AID system is trusted. Typical IDAs that depend on a network of discrete traffic sensors include:

Whatever algorithms are chosen, they will need to be calibrated and matched to the available types of sensors. It can be advantageous to simultaneously use multiple IDAs that have complementary characteristics – or apply different IDAs to different scenarios. To ensure accuracy, the data from individual sensors needs to be filtered before it is used by the IDA. (See Data Aggregation and Analysis) When an incident is detected, operators can draw on additional information from other sources such as CCTV cameras – and apply their own judgement to manually validate the incident.

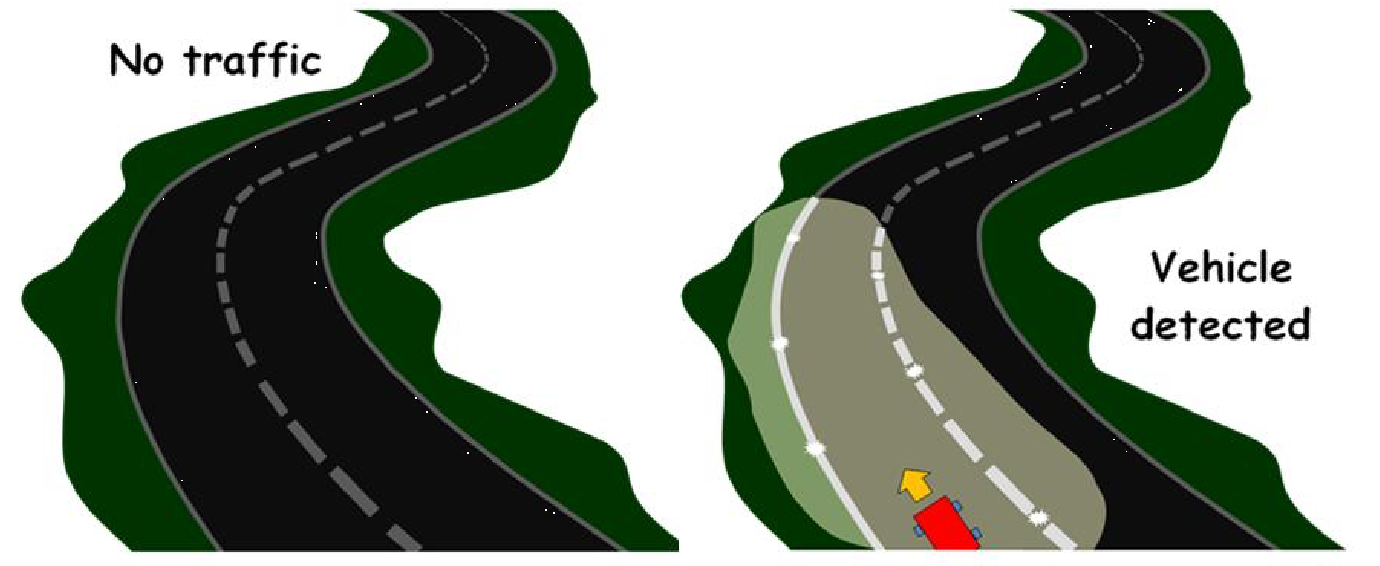

IDAs can be applied to existing video streams. The IDA is either integrated within individual CCTV cameras or applied to a group of cameras to permit discrete events to be detected, such as stopped vehicles – as in the image below, debris, and vehicles driving erratically or in the wrong direction. Video-based AID detects events visually anywhere within an image - not only in the driving lanes but also on hard shoulders and emergency refuge areas regardless of the road surface material (concrete, asphalt, gravel or metal).

Stopped vehicle detection – interurban highway

AID depends on there being comprehensive coverage by sensors and/or CCTV cameras of the road network to be monitored. The accuracy and geographical reach of AID can be improved if additional sensors and cameras are deployed.

Traffic sensors installed for surveying purposes or for general traffic monitoring may not be suitable for AID for various reasons (loop systems may detect traffic presence but not changes in traffic speed, existing CCTV cameras may not have image processing capability). In most cases additional sensors will be needed to ensure the reliable detection of incidents. (See Vehicle Detection)

Images taken from a CCTV camera dedicated to AID can be used to provide reliable information on occupancy, flow and speed - whilst also serving its primary purpose of surveillance - enabling an operator to validate an incident reported by the IDA.

For a CCTV-based AID strategy there are a number of issues to consider:

For night-time conditions or where streetlights are unreliable, thermal cameras are effective at detecting vehicles on verges, or pedestrians and animals on roads. Thermal cameras also perform better in foggy conditions - so are useful for simple traffic monitoring.

Whether existing or new cameras are deployed, pre-recorded video of incidents can be used to test the performance of an AID system under different conditions, typically described by three parameters:

If hard shoulders are designated as normal travel lanes on a part-time basis (“hard shoulder running”) then an AID system, as part of a Decision Support System (DSS), is necessary to ensure the safety of road users. For example, if an incident is detected on the hard shoulder during hard shoulder running, approaching vehicles need to be alerted and the hard shoulder closed automatically or under manual supervision.

Excess traffic demand may cause a breakdown in traffic flow that results in the formation of queues and increases the risk of vehicle collisions and other incidents. An IDA function needs to be able to detect unusual queues, compared with normal traffic flows – adjusted for time of day, the day of the week and holiday periods.

Legacy networks of CCTV cameras can support AID - although a video decoder will be needed to prepare the video for computer analysis. Depending on the manufacturer, many legacy CCTV cameras, including those with a PTZ function, can provide video to support an AID function. It is likely that existing cameras have been positioned for surveillance – and may not be suitable for the image processing required by camera-based AID. They will need to be repositioned to ensure high detection accuracy and to remove the effects of light reflection (from vehicle headlights, wet road surfaces, low-level sunlight).

Inductive loops buried beneath the road surface or passive roadside detectors are able to provide a comprehensive view of traffic flows on the road network - but the impact of traffic conditions on individual vehicles can be difficult to understand. Detecting an identified vehicle as it passes through known locations on the network can serve as a “traffic probe”.

Probe vehicle monitoring is emerging as a critical technology that complements static sensors, CCTV cameras and ad-hoc reports, whilst also providing information on the speed and flow of a road segment. Road network monitoring is traditionally provided by static detectors such as inductive loops and CCTV cameras located on strategic roads with the highest volumes of traffic. (See Vehicle Detection) This is supplemented with ad-hoc reports from the police, emergency services and members of the public, which contributes to the development of a comprehensive view of the roads (including secondary or tertiary roads) – but the cost of monitoring a large area is often prohibitive.

Probe vehicle monitoring is where a vehicle is equipped to track journey time - for example by tracking Bluetooth signatures between successive points or by using in-vehicle navigation (GNSS). Speed and point to point journey time data is stored and communicated back to the management or control centre to:

Probe vehicles can generate more detailed information on the impact of traffic conditions – by providing the data to calculate, for example:

A probe vehicle must be capable of being reliably and uniquely identified at more than one discrete location. For example:

Roadside-based detection technologies make it possible to detect the same vehicle at different locations on the road network so it can be used as a traffic probe. The vehicles must have a specific identifier - such as a readable number plate, a Radio Frequency Identification (RFID) tag, or vehicles carrying a device (such as mobile phone, satellite navigation system, computer or portable media device) with a Bluetooth transceiver that is discoverable. Probe vehicles can also be categorised as “passive” or “active” - although sometimes this is an arbitrary distinction:

The techniques of Probe Vehicle Measurement have developed to ensure that any data collected is combined to create average road link performance and is not personally identifiable.

The most common technologies for probe vehicle monitoring can be split into roadside-based detection and mobile device reporting. Examples include:

Satellite-based in-vehicle systems are often integral to fleet management applications for freight and commercial operations. These vehicles often travel along strategic highways and can be a suitable for a fleet of probe vehicles to cover the network. (See Freight and Commercial Operations) Satellite technology can also be used for road user charging. (See Electronic Payment)

In general, the greater the number of probe vehicles, the better the quality and accuracy of the information that is derived. Small samples of probe vehicle may not deliver high enough accuracy on a specific road or for a specific road network. The behaviour of a single vehicle (such as a bus) may not reflect the general traffic flow – so it is important that the probe vehicles are a high enough proportion of the total to meet the required levels of accuracy.

A study by the Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT) suggested that sample sizes as low as 45 RF-tag-equipped probe vehicles per day – with average 30-minute headways - could yield useful data on the occurrence, duration, severity, and frequency of congestion. Probe vehicle sample sizes varied depending on local road networks, traffic patterns and other factors.

Increasingly, road users are being informed about road network conditions, before and during trips, through social messaging and third party navigation systems. They may receive traffic reports from other sources such as public radio stations, mobile phone alerts (Twitter, Weibo or other social messaging sites) and third party navigation applications. Traffic authorities can monitor messaging services such as Twitter (South Africa) and Weibo (China) for traffic information that may help complement static vehicle detectors.

The provision, collection and use of data from road users raises legal and institutional issues relating to privacy, data collection, ownership and sharing. (See Legal and Regulatory Issues)

Static detectors and probe vehicle measurement provide complementary views of the performance of the road network through roadside observation and by passively monitoring individual vehicles. These techniques are adequate, most of the time, for managing traffic operations. AID can improve their effectiveness in responding to accidents and planned events. Other sources of data that can help better manage a road network include:

During an incident, the mix of traffic data available to road operators is likely to change, with increasing amounts of information arriving from both reliable known sources (“trusted”) and unproven (“untrusted”) sources. Some of the information received may conflict with current knowledge - potentially highlighting a change in circumstances or new and unrelated incidents. The effective use and management of all data sources is critical to effective network operations, particularly during the incident management process.

A well-designed cost-effective traffic management operation needs to recognise the existence of other data sources and to provide the means to include them in its traffic and incident management strategy. Data sources and data owners, other than the highway authority or road operator include:

The figure below shows the role of other parties alongside road operators in the traffic data collection process. By way of illustration:

Whatever the source of the data, it needs to be assigned a level of trust by the road operator to help it prioritise sources and ensure that the reliance placed on a specific source is appropriate. Data sharing agreements between organisations should clearly specify each parties’ respective roles and responsibilities – and be formally documented (perhaps in a Memorandum of Understanding) and agreed by all parties. The road operator will also need to develop a policy and procedure for handling reports by the public – and to record this for its staff in an operations handbook.

Organisational Model and the relationship with other parties. Reproduced by permission of the EasyWay Consortium (http://www.easyway-its.eu.) a trans-European project co-financed by the European Commission.

The variety of other data sources available is matched by the variety of data formats and the trust that may be placed on the sources. The most cost-effective data sources for developed and developing countries are existing sources – but it is important to check that they are reliable and suitable if they were designed for another purpose (such as a weigh-in-motion sensor). A rigid definition of sources may not be relevant – and a traffic operator will need to apply discretion and judgment to the value of the reports received from them. Whatever the source, all data collected needs to include as a minimum - location information and a time stamp.

Where additional information is needed to improve traffic operations or incident management, site observers may be deployed to specific locations to collect survey data, report on traffic behaviour at planned events or to provide real-time information by voice (mobile phone or private mobile radio) or handheld computer at the location of an incident.

Standardisation of data formats, protocols and communications interfaces is desirable to avoid misunderstandings or conflicts between organisations – such as the data provider (a Police Incident Control Centre) and the data receiver (the Traffic Control Centre – TCC).

If a data interface is required, a technical interface standard can help ensure that a TCC can add new sources easily - whether the data is provided from another system (Centre to Centre, C2C) or directly from a device located in the field (Centre to Field, C2F). Examples include:

There are many global trends that are likely to stimulate innovation and the adoption of new technologies, systems, applications and information chains in the monitoring of road networks. Some of the technological, application and organisational elements of the future of road network monitoring are already being implemented, although their use is not widespread. Innovations in wireless communications, the increasing use of smart phones and advances in automotive design are having an impact. For example, consumer “smart phones” are used to informing road users of changing conditions – and vehicle sensors are used to detect incidents. (See ITS Futures)

The deployment of more sensors allows Traffic Control Centres (TCC) to benefit from more up to date and detailed view of traffic conditions - complementing static detectors and CCTV cameras. High availability, high bandwidth, standards-compliant, fixed and wireless communication networks are increasingly used on busy urban and interurban highways to support multiple services.

Traditionally, intelligent transport systems have been biased towards infrastructure-based or vehicle-based applications - often led by government and vehicle manufacturers. Recent innovations in mobile phones - such as navigation, imaging and multiple short-range communication radio modules - are being integrated into lower cost phones. They provide users with technologies that can sense some characteristic of their local environment and interact with it. This is one of the most important elements of road network monitoring applications.

The Vehicle-to-Infrastructure (V2I) initiatives that are active in the US, Europe and Japan provide the potential for all vehicles to perform probe functions for private sector service providers and public traffic management authorities. The challenge will be dealing with all of this information, captured over an ever larger area. Innovations in visualisation tools such as Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Knowledge-Based Expert Systems (KBEST) are already being commercialised and provide increasingly valuable assistance to TCC staff in monitoring the state of the network – whatever the source of the data.

The combination of Vehicle to Vehicle (V2V) and Vehicle to Infrastructure (V2I) means that road users will be able to share their own sensor data (such as speed, grip, surface temperature or queuing) with a centralised computer facility for interpretation or direct transmission to other vehicles. A vehicle without sensors may still be able to transmit road condition status gathered through in-vehicle monitoring – based on simple indicators such as use of fog lamps to indicate fog and extended use of windscreen wipers to indicate heavy rain. Data collated from enough vehicles (with or without sensors) could enable an accurate picture to be produced of flow rates, speed and driving conditions.

Stakeholders in traffic data collection include:

New opportunities for road traffic data capture and consumption between road users emphasise the need for cooperation between organisations on data sharing. (See Other Sources) A structured model for traffic data collection and interpretation - where the interfaces and responsibilities are well-defined - is being supplemented by new sources of data and analysis exchanged between users and third parties, where the TCC has little or no influence on the quality of data or its use.

Social network messaging and navigation service providers already provide real-time traffic data to road users, specific to the user’s location, based on crowd-sourced data. These sources can improve the effectiveness of a traffic and incident management operation, at a lower cost than direct investment in measurement systems. This is particularly useful for a road operator:

Whilst crowd-sourced data can provide real-time traffic information at low cost - the level of detail depends on the density of numbers of mobile sensors. Less information will be provided during off-peak periods and where the proportion of the crowd that provides useful data is low. Road operators also need to be aware that the algorithms developed by third parties to meet commercial objectives may not be consistent with the approaches required for traffic management or for incident detection.

The road operator needs to bear in mind that it has a responsibility to all road users - not only those that have access to advanced mobile phones or vehicles equipped with on-board sensors.

Static roadside sensors are becoming more accurate and are available at lower cost. Improved methods of planning are being developed to make best use of available budgets. They recognise that the purpose of any detection scheme – and the reliability of individual detectors – will influence decisions on where detectors are deployed. For example, the optimal planning strategy for journey time monitoring would require detectors to be distributed widely - whereas flow measurement would demand a greater concentration of detectors to ensure sufficient coverage with some redundancy (to provide resilience in the event of equipment failure).

The investment in deploying new sensor networks is driving the development of combined sensors. For instance:

Transferring information from these types of devices requires some form of low power communications and development of Mobile Ad-hoc Networks (MANETS). This will enable sensors to transfer data between themselves over short distances and to fixed roadside data receivers. In dense urban environments, a network of vehicle or environment sensors can be installed cost effectively.

Extending this further into the future, combining MANETS with miniature sensors and some means of ‘harvesting’ energy from the environment may result, one day, in ‘smart dust’. This is an emerging technology comprising a system of tiny Micro-Electromechanical Systems (MEMS) that can detect light, vibration, temperature, magnetism or chemicals. In the future they be embedded in materials such as the white paint used to indicate traffic lanes.

These types of pervasive sensing and communication (via fixed roadside wireless receivers) can further improve the visibility that the Traffic Control Centre (TCC) has of local traffic conditions.

Multi-sensor roadside system

Intelligent hardwired road stud, including LED signal and external interface

Intelligent road studs - active lane delineation

Intelligent road studs – simulation

The increasing variety and geographic coverage of static and mobile sensors presents TCCs with major challenges in interpreting data and making rapid decisions on the appropriate response. This is particularly the case when traffic conditions change quickly because of an incident. Artificial Intelligence (AI) is already being trialled to optimise traffic signal timings, to make better use of available road capacity and to reduce the environmental impact of traffic. (See Intelligence in Transport)

Knowledge-based Expert Systems are able to maintain reference models of normal traffic conditions anywhere on the road network and can provide immediate recommendations on alternative traffic plans in the event of an incident. These are being trialled in London and are planned to be used in Hong Kong as part of its Traffic & Incident Management (TIM) System (See PDF 3202 Case Study Traffic & Information Management (TIM) System, Transport Department (Hong Kong))

Other trends include: