Road Network Operations

& Intelligent Transport Systems

A guide for practitioners!

Road Network Operations

& Intelligent Transport Systems

A guide for practitioners!

As with any other branch of information technology, ITS has seen an explosion in the capacity to generate, process and store data over the last decade or two, which will continue using what is nowadays “normal” computing capacity. Large volumes of data can be easily captured, collected, and stored in real-time and processed in a variety of ways. ITS applications draw on a wide range of data sources including details of vehicles, personal details of drivers and public transport users, bank details for electronic payment (tolls, tickets or a congestion charge), origin and destination of journeys, vehicle and personal location.

Data processing and data privacy legislation is constantly evolving to keep a balance between what the national authority and the general public consider desirable and reasonable in handling an individual’s or organisation’s data (the subject’s data). The principles of contract law and privacy legislation apply equally to ITS as they do to any other area of life. Ignoring these principles creates a risk that the ITS application will become a point of friction between authorities and the public. The challenge is to bear this in mind, even where the information appears at first sight to be non-sensitive.

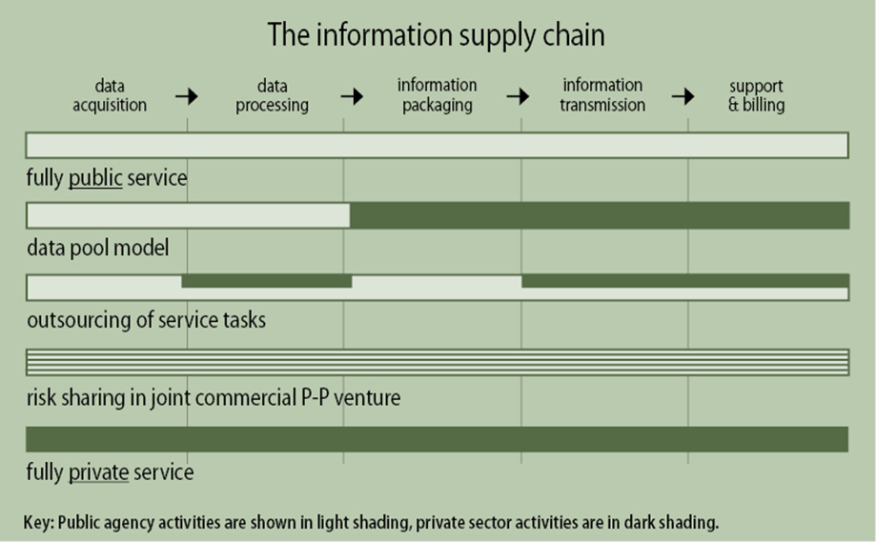

ITS applications cannot function without systematic capture and processing of data. The legal and organisational arrangements involved may be quite complex for even simple applications – such as real-time arrivals at a bus stop. In the case of ITS-based information services the flow of data and content can be organised between the public and private sectors in different ways – as shown in the figure below. The development and delivery of the information service to the end user depends on partnerships and contracts – from data acquisition through to service support and billing. Each of the parties involved will be subject to contract law and enforcement. (See Case Study: Data Sharing, New Zealand)

Data explosion is not an ITS phenomenon. It mirrors what is going on in social media, on the Internet, in marketing and other sectors. As a result, many countries have legislation and regulation governing how to data should be collected and handled. The ITS sector operates within these frameworks. As with all national legislation, they vary from country to country – but some broad and simple principles apply universally and should be taken into account by ITS practitioners even if there is no relevant legislation in place as yet.

The tension in this area is created by the basic question of who controls the data:

There is often anxiety amongst the general public (who are often data subjects) about what exactly is being recorded, how personalised it is, to what use it is being put, and for how long it will be stored. This concern is not always logical. For instance mobile telephone records and electronic banking systems create a comprehensive, maybe intrusive, data picture of individuals – but mobile phones and bank cards do not often receive the same level of criticism as the identification of vehicles through Automatic Number Plate Recognition (ANPR) (See ITS Technologies) for the purposes of:

The creation, use and storage of transport data – as with any other data – is a sensitive area and ITS practitioners should make sure they remain within the laws and regulations governing data processing in the country in which they operate.

It is sound practice to only collect what you need, restrict this to data actually required for the work to be done – and to discard the data once its purpose has been fulfilled. For example, for the purposes of calculating journey times – it is not necessary to record the names and dates of birth of drivers.

The Stockholm Congestion Tax back office permanently deletes all vehicles and journey data once the journey has been paid for or any dispute relating to the journey has been resolved. Since this office generates tax bills monthly, hardly any data is kept for longer than a month. This is an example of good practice. (See Case Study: Stockholm Congestion Tax)

Restricting types of data, encrypting data irreversibly, and having strict rules for data handling and storage, including time limitations, will keep an ITS application within the bounds of good data practice.

Data should only be personalised when it needs to be. Data collected for tolling (See Electronic Payment or Law Enforcement) purposes has to be personalised to be useable – but even with tolling this can be minimised. For example, the collection of personal data (such as exact trip location) for tolling can be minimised by using a “thick client” – where most of the transaction processing is done within the vehicle – reducing the amount of information sent to the back office to generate the toll charge. When collecting data to establish traffic flows (See Network Monitoring) or public transport usage loading (See Passenger Transport), the names and addresses of travellers are of no importance and should not be collected, even though the possibility exists.

It is a generally recognised principle that information should not be recorded just because it exists and can be recorded. It should only be recorded if it is needed for the process being carried out. For example, vehicle speed data collected on motorways to determine traffic flows – the licence or number-plate data would usually be encrypted in an irreversible way – so that all the data processor knows is that the same vehicle passed point A at x time and point B at y time. Even if the operator wished to reverse the encryption process and identify an individual vehicle, this is not possible.

Data should only be stored for as long as needed. “The right to be forgotten” is a phrase sometimes used to express this. Once the process for which data was collected has been carried out – whether this is to generate a toll charge or to authorise a public transport passenger to undertake a journey – it should be discarded. If there is good reason to keep it – for instance, to carry out some kind of statistical analysis or forecasting – it should be irreversibly made anonymous before storage.

Data subjects should be able to check on the personal data held relating to them, and there should be a process for challenging – either the content of the data or the fact it is being stored at all.

Season tickets usually generate detailed personal data about the purchaser, such as their address, date of birth, bank details through their payment, and gender. Ticket use will generate detailed trip data linked to a person if the public transport (See Passenger Transport) system uses gates, readers or scanners such as the one illustrated in the figure below. Individual “paper” tickets, as a rule, would only generate data about the location of the purchase and the trip. It is good practice to offer anonymous ticketing and cash payment options whenever possible.

The movements of trains, buses and other forms of public transport are often controlled and/or monitored by ITS – and so, record data. This can lead to privacy (See Privacy) issues for drivers and other staff – and their representative bodies – such as driver associations or trade unions – voicing concerns. On the other hand, location applications can improve the safety of public transport staff.

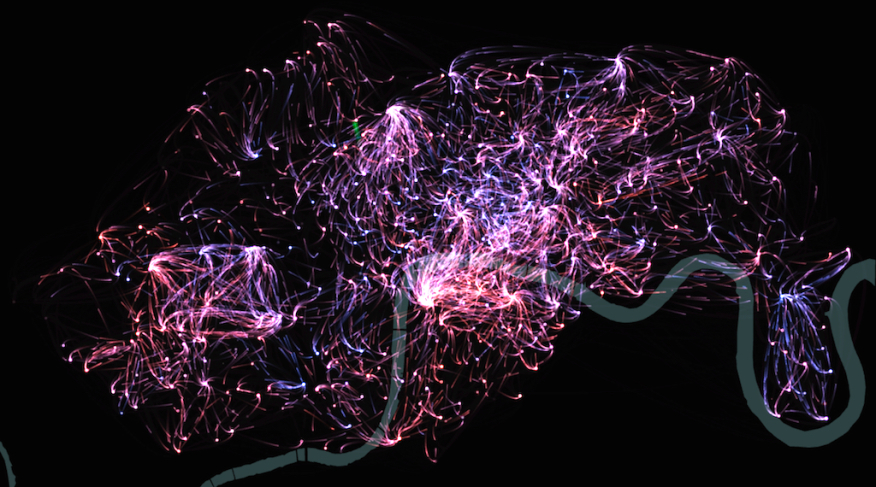

Data are generated through many different ITS traffic management systems in use (See Network Monitoring). Vehicles are identified and their location, direction of travel, and speed is recorded – both to enable optimal traffic management at the time, and for future modelling and forecasting. The figure below shows how data from London’s cycle hire scheme can be used to visualise cycle traffic movements. This type of data collection may be completely impersonal – such as loop detectors which only establish that a vehicle is there and the speed at which it is travelling. It is also capable, though, of detailed personalisation – if the vehicle is identified by ANPR and an image captured enables the identification of driver and passengers. Good practice is to only record the data needed for the job in hand, and to irreversibly encrypt or discard the rest.

If an accurate tolling (See Electronic Payment) charge is to be levied, a lot of personalised data regarding the vehicle, its keeper, its location and possibly its exact trip details, and the customer’s bank details – have to be recorded. Good practice is to discard this after an agreed period – after which the driver no longer has a right of challenge against the charge.

New ITS applications of driver support systems (See Driver Support), autonomous vehicles and cooperative systems need to be considered carefully before establishing good data handling practice. These systems rely on an enormous amount of location and trip data in order to be safe and effective. There is no reason, though, why this data should be kept and stored after completed trips without being made anonymous.

A fairly new area of ITS data is crowd-sourced data. Social media and technology – such as Bluetooth (See ITS Technologies) - offer the opportunity to generate or collect comprehensive and detailed travel data relating to individuals. This can either be with their active or implied consent – or without their knowledge. For instance, a keen user of social media who uses platforms such as Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn and TripIt to broadcast their whereabouts can be considered to be consenting to their travel profile being constructed. By contrast, logging the movements of somebody who has not realised that their phone has Bluetooth and that it is enabled – is at the other end of the scale and can be reasonably considered as an invasion of their privacy. They have not consented to their data being used and are not aware that they are generating data. In many countries, the fact that they are anonymous would still not make it acceptable to use their data.