Road Network Operations

& Intelligent Transport Systems

A guide for practitioners!

Road Network Operations

& Intelligent Transport Systems

A guide for practitioners!

In the modern world, many processes are automated by machines. Whereas people would previously have been responsible for completing each individual process, the role of the person is typically now limited more to monitoring the machines that undertake those processes. The idea is that machines are employed to do the simple, repetitive tasks at great speed – and a person is on hand to sort out any problems that might occur. In theory this plays to the strengths of both machines and people. The (so called) “irony of automation” is that the human takes on the role of system monitor – and that this role is far from suitable for human attributes.

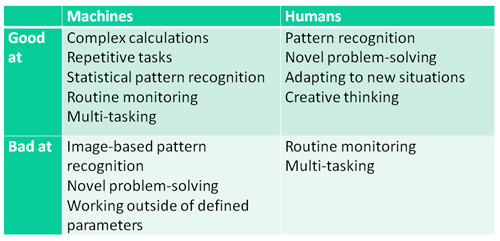

People and machines are good and bad at different tasks and roles. The figure below highlights some of the key distinctions:

In ITS the role of automation is often to remove from the user responsibility for tasks that people generally find difficult or mundane – so they can concentrate better on tasks which either cannot be automated or cannot be automated efficiently and effectively.

It may not always be easy to make a clear distinction in the appropriate division of labour. It may be that a system can only automate parts of a task, or that there is an output from an automated task that must be fed back to the user at some point. Issues can arise if the division of labour is such that a user is required to perform a function for which they are not suited, as a direct result of that division.

Even if people are given roles suited to their skillsets, and tasks are suitably reallocated for automation so that the user is able to only consider the critical tasks – performance may be compromised if the user is so far removed from the task (“out of the loop”) that they are unable to intervene effectively when required.

People perform poorly when overloaded, but performance also drops off when under-loaded as it can cause the user to switch off mentally. It may be that any corresponding loss of attention means an operator fails to spot an important development within the system. Even if operators are alerted to an important development by an alarm – their understanding of what needs doing to rectify the issue may be impaired if they have not been kept sufficiently in-the-loop to maintain their situational awareness. This awareness is essentially the user’s understanding of: what is happening within the system, what will happen next and what the implications are. Loss of situational awareness could arise through poor task allocation within the system, as a result of cognitive under-load or through the user placing too much trust in the system to perform as expected.

If a situation requiring action by the driver arises, automation may mean that the system warns that an intervention is necessary – even if the user is sufficiently alert and knows what to do. If the alert is not given early enough, the operator may be unable to act, despite knowing what to do in principle.

Automation can have negative consequences and designers will need to consider the possible implications of automation before introducing it into any design. Correct use of automation can prove extremely useful to the operator and to overall system performance. Transport systems and networks are often highly complex and ITS offers the potential to use technology to simplify aspects of these systems from the perspective of the user. Automation can be a useful means of reducing the overall complexity of the system so that individuals are able to focus more clearly on the most important processes. The key requirements in order to be able to do this effectively and safely are effective task allocation and the avoidance of overload or under-load.

Ideally, designers should seek to obey the following principles:

To avoid overload/underload, designers should also take account of the following principles: