Road Network Operations

& Intelligent Transport Systems

A guide for practitioners!

Road Network Operations

& Intelligent Transport Systems

A guide for practitioners!

The tasks and functions performed by the private sector have evolved over time from the provision of non complex, well defined, well specified and generally low risk services through to complex, minimally defined, minimally specified, high risk services. In many countries private sector providers are responsible for a range of tasks that previously were undertaken by road authorities. In many of these contractual arrangements the private sector operates and accepts risks that were traditionally borne by the road authorities. For example, the project financing of road infrastructure and services are often transferred to the private sector; also bearing the revenue and asset condition risks of projects.

The role of the private sector in the financing, construction, maintenance and operation of road infrastructure and services has evolved. In parallel, the methods used to procure the required works or services have evolved to take account of these developments. (See Procurement and Competition and Procurement) Contract formats have also evolved to facilitate an increasing the role for the private sector, moving the responsibility for and the management of risk from the road authority to the private sector provider. New forms of contract have been developed to clarify roles and responsibilities of each party in order to minimise the risk of project failures, control development costs and secure effective risk management.

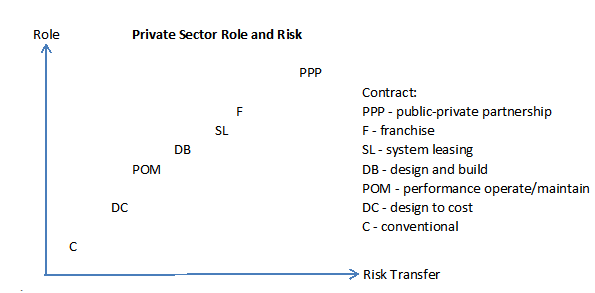

The chart below demonstrates the varying role of and risk transfer to the private sector and contract types.

ITS technology and services are evolving all the time. So too are the road authority and road user needs. (See Business Framework and Road User Needs) Road authorities should be very mindful of possible contract variations during the life of an ITS project, for example in the form of additional service requirements or changes to previously agreed service levels. Invariably, any contract variation - post award - is likely to be costly to the authority. Therefore it is advisable to seek to enter into an ITS contract that has a fair degree of flexibility for contract variation. Very roughly, the degree of flexibility needed for contract variations is inversely proportional to the level of risk that is transferred to the private sector. Road authorities can help themselves by avoiding hasty procurement and spending quality time to define comprehensively the ITS services needed now and during the lifetime of the project, and incorporate the contingent requirements as future options. The contract period should be tailored to no greater than the asset life of the project - this will allow the authority to refresh its needs periodically and take advantage of market competition.

Contract monitoring involves the active recording, assessment and control of all aspects of service delivery during the lifetime of the project. This needs to be specified in the agreement between the road authority and the ITS project contractor. (See Performance Measures) It involves three principal activities:

The methods and procedures for post-award contract monitoring are typically spelt out in the agreement between the authority and the supplier.

The effort required and level of detail involved in contract monitoring will vary at different stages during the lifetime of the contract. There are 3 distinct phases:

The activity of recording the amount, quality and timing of service delivery is increasingly - though not necessarily - carried out by the supplier based on a self-completion quality management system, which will also be specified in the agreement. This is particularly common with contractual arrangements involving a high degree of risk transfer, such as franchising and Public-Private Partnerships (PPP). (See below and link to Public Private Partnerships)

Needless to say, the road authority's contract monitoring team should maintain a good working relationship with the ITS service provider. This hopefully allows the parties to iron out any challenges without involving a third party.

Alternative contract arrangements for road ITS projects are described below.

Conventionally, the contracts used to procure these services have been straight forward, whereby the private contractor is paid an agreed amount to undertake a specified task. The payments will be calculated on the measured amount of works delivered, the period of time the services are being delivered or on the actual costs incurred by the private sector to deliver those services, plus an agreed margin.

Another feature of conventional contractual arrangements is the discreet nature of the works or services, to be provided under separate contracts. For example, ITS system design may be undertaken by personnel employed by the road authority or by consultants engaged by the road authority - under a separate arrangement to that of the construction works. Later operation and maintenance activities when the system is up and running may be the subject of yet another contract.

Under these contractual arrangements, the road authority essentially retains the risks relating to when and how the services are delivered and the levels of service to be provided. It also retains the asset obsolescence risks.

Option 1 is a two-stage approach: the agency issues a request for proposals to a short-list of contractors who have all pre-qualified (in other words, each one has already demonstrated to the agency’s satisfaction that they have the necessary skills and capability to carry out the work.) The total budget available for the project is identified. At Stage 1 each potential contractor is required to submit a detailed proposal covering the methods they will use to meet the contract requirements, the suppliers to be used, and their outline plans for the work. Revisions to this package can be made to reflect common changes that would be required of all suppliers to meet system requirements. Contractors with acceptable proposals then compete at Stage 2 on the basis of costs and other criteria. There is no detailed design work done until after the contract is let.

Option 2 is a one-step selection that is based on the Stage 1 submittals - as above. The contract will require the development of a detailed design document to be agreed by both parties before proceeding with system implementation. Upon approval by both parties, that document becomes the basis for the final contract. If no agreement is reached, the contract is terminated and the payment is based on the agreed expenditure involved in developing the detailed design.

As the complexity of the infrastructure and services being delivered by the private sector increased, many authorities recognised that the supplier of those infrastructure and services may offer better value by undertaking both the design and construction tasks involved. This was seen as a way for the private sector to not "over design" and encourage "fit-for-purpose" designs which may not be onerous to build.

With these contracts, the road authority specifies the general details of the required project. For example, for a road toll system the authority specifies the traffic volumes, number of toll lanes at the toll plaza, the average and maximum transaction times to be incurred by road users. The private sector supplier has the responsibility of designing and constructing the ITS infrastructure to meet those specified details. It is normal for these contract arrangements to require the private sector supplier to warrant the quality and performance of the assets for a significant period, even up to the first maintenance cycle of the asset. In some contracts the same private sector entity that constructed the ITS asset may be retained to also operate and maintain the asset for specified periods of time An example is the accident response system and traffic management centre in Madhya Pradesh, India (See http://mprdc.nic.in/RFQ_for_ARS.pdf ).

A possible downside of employing design and build contracts over a sustained period is that the road authority may lose some of its knowledge on current practice and be less well informed about approaches that may be evolving in the road industry. In contrast, the private sector partner may be more current in its knowledge and be able to increase the benefit of having the designer being in “touch” with the constructor.

Public Centred Operations - in this model, the public agency retains a high degree of control, assumes the major burden of risk and takes on the main financial responsibility for the ITS operation. But even where the responsibility for operations remains firmly in the public sector, there is often a role for private companies in providing specialist support. Out-sourcing of routine ITS support activities, like maintenance of traffic signals and signal controllers, is now well-established in many countries. Other services such as software maintenance and technical support for a traffic control centre may be out-sourced as well. These support contracts can usefully incorporate performance targets, such as minimum response times and performance criteria needed for safe operation (for example traffic signal maintenance at critical intersections). The public sector client will maintain control of the performance targets and carry out performance monitoring in the usual way.

Contracted Operations - a much higher level of delegation is to appoint a private sector company to manage and service the operation, for example, through a facilities management contract. The public agency retains control of operational policy and gives direction but the private company runs the everyday operation and maintains the ITS services. The authority draws up an output specification for the product or service they wish to see developed and invites companies to submit competitive bids to complete this work. Selection is based on the best value for money and quality. The subsequent partnership is pursued on an exclusive basis for the period of the contract. Normally, a “request for partnerships proposal” is used to ensure that the usual public procurement rules of open competition are respected when selecting the preferred partner.

Under the franchise model, management of the entire operation of the ITS service or facility is handed over to the private sector with a very high level of delegation over its development. The public sector agency will specify the terms on which a private company can take on the franchise, but it stands back from day-to-day involvement in the operation. Its role is mainly to see that service standards are maintained and service users are not subjected to unfair pricing. It is normal for the franchise-holder to be appointed after competitive selection. The franchise is usually held on an exclusive basis for a number of years, after which the franchise is usually re-tendered on the basis of an open competition. Franchising opens up the possibility of private capital for the business if there are adequate revenue streams to finance the borrowing. This entrepreneurial approach is seen, for example, in France, Italy, and the USA, where privately operated toll road operators have adopted electronic tolling methods to save on labour costs and reduce the delay for their customers at toll plazas.

Under a franchise arrangement the city or regional transportation authority solicits proposals from potential contractors based on a statement of objectives. Supporting information is requested on the contractor’s capabilities, the resources that are currently available, and the budget that will be required from the public agencies. A franchisee will be selected based on an evaluation of the level of service to be provided, their business plan for future self-support of the operation, the guaranteed levels of information available for free, and the use and timing of public funds. Qualifications and experience will be included in all elements of the evaluation. The maximum time to self-support (typically five years) and maximum franchise period (say, ten years) will be specified. The franchise may confer an entitlement to innovate new revenue-generating services on the back of the basic ITS concession. However, if the business assumptions for the franchise are not sufficiently robust the business will collapse before the franchise has run its full term.

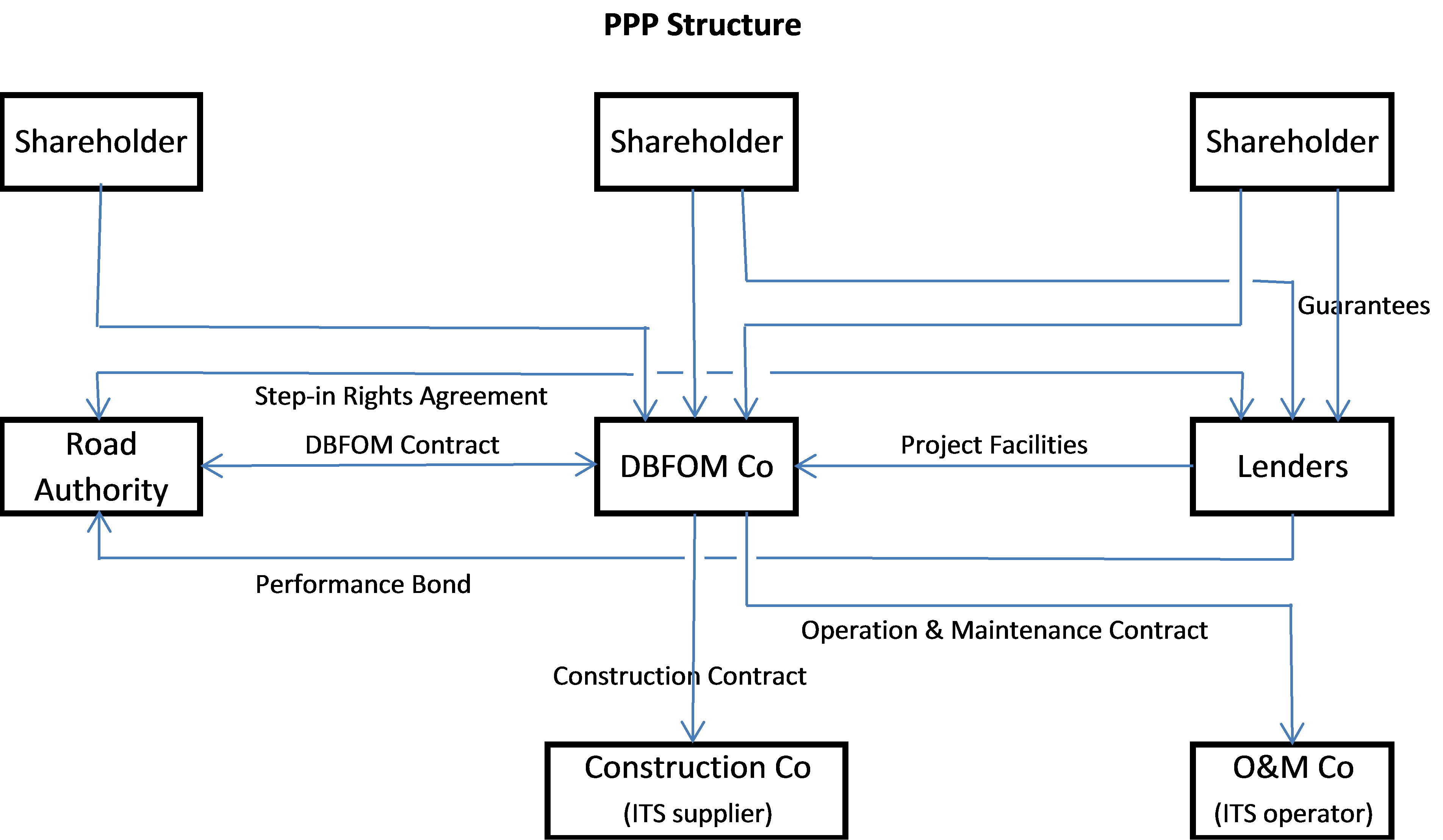

PPP contracts are usually used for large greenfield or significant rebuilding and improvement projects. They typically involve the highest level of private sector participation and risk transfer, including providing the project financing and bearing a level of revenue risk. A typical PPP arrangement will involve tens of contracts and stakeholders because of the numerous responsibilities conferred to the concessionaire. The concessionaire is typically a consortium made up of designers, construction companies and ITS operators and maintenance providers, as well as the equity investors. It can be summarised schematically in the chart below.

Under a typical PPP arrangement, the road authority determines what ITS infrastructure needs to be built or significantly improved to deliver the required ITS services. It defines its needs (for example the roads and highways to be included, the monitoring sites, the VMS locations) and carries out sufficient preliminary design work to be able to obtain environmental permits and estimate the project’s construction costs. Should land be required the road authority usually acquires it for the project. After a competitive procurement process, a single contract is entered into between the road authority and the private sector partner (often called the concessionaire). The concessionaire has the responsibility to design, build and finance the project according to the road authority’s criteria and then to operate and maintain the road and associated structures, including major maintenance, for an agreed period. In addition, the concessionaire must maintain the ITS asset to meet the hand-back requirements at the end of the concession period. This may require the concessionaire to carry out a remedial improvement programme to meet the hand-back requirements during the last few years of the contract period.

In return for its services, the concessionaire receives payments from the road authority and/or the road users. If permitted by the contract, there may be additional revenue from third-party users of information mined from the ITS system. Although some payments may be made during the construction period, most of the ITS capital costs and all of its operating costs are typically re-paid during the operating period. These payments may be conditional on the availability of the ITS services and the outcomes of a set of performance indicators.

In a PPP contract, significant risks are transferred from the road authority to the concessionaire. Risk transfer in any PPP is very case-specific and can include:

More information on the use PPP contracts, including an Austrian and a Mexican case studies is available the PIARC Technical Committee report Financing, Managing and Contracting of Road System Investment available for download at: http://www.piarc.org/en/publications/search/.