Traffic Management refers to the combination of measures that serve to preserve traffic capacity and improve the security, safety and reliability of the overall road transport system. These measures make use of ITS systems, services and projects in day-to-day operations that impact on road network performance.

Central to this approach is the development and integration of a set of traffic management measures appropriate to the local and regional requirements – and to achieve this through a planning process that makes use of systems engineering, standardisation and documentation, and performance management.

The emergence of ITS in the field of traffic control has enabled a number of new concepts to be applied in the framework of innovative operational systems. Examples include bus and tram priority, and pollution monitoring. These features are starting to be deployed amongst established traffic management systems.

When traffic control systems have been found to reach their limits and where adding capacity or new building of road infrastructure is not feasible, further measures may become necessary. These may include restrictions on the free use of individual vehicles through Electronic Road Pricing (ERP) or a Congestion Charge. (See Congestion Charge)

Some examples of traffic management measures that may feature as part of a network operating strategy are:

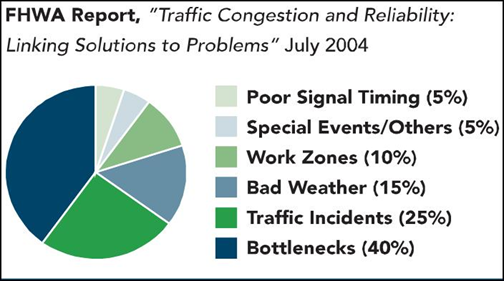

Some years ago, a study in the USA set out to quantify the leading causes of traffic congestion. The results, averaged for all roadways, are shown in the Figure below. A large proportion is attributable to road bottlenecks and poor signal timing (40% and 5% of all congestion in this example). This congestion is repeated on a daily or weekly basis and is referred to as recurring congestion.

Although the data shown in the figure below is particular to the USA, the high incidence of bottlenecks points to issues of network management and infrastructure inadequacies. This is the case particularly at road intersections and junctions, and can be seen across the world. Extensive traffic management measures are deployed to address these problems. The proportions in the figure are composite estimates derived from many past and ongoing congestion research studies. They can be considered as enduring proportions as they continue to feature in the current equivalent (2015) FHWA publication

Sources of Congestion (USA 2005)

As the figure shows, the leading cause of non-recurring congestion is traffic incidents. Nearly all of non-recurring congestion can be mitigated by better operational strategies. Even with bad weather, ITS can help with mitigation. Dealing with more severe emergencies usually presents orders of magnitude in challenges – but again, better operational planning, preparation and response can help mitigate many of their impacts.

Programmes that seek to minimise non-recurring congestion include the coordination of regional road network operations, traffic incident and emergency management, work zone management, road weather management and roadway ITS maintenance operations. Other approaches to congestion mitigation include traffic control and demand management. (See Traffic Control and Demand Management)

Specific guidance on a number of traffic management services have been developed by European road authorities and operators as part of the European “EasyWay” project. The EasyWay ITS deployment guidelines are available for download at http://dg.easyway-its.eu/DGs2012

The Chartered Institution of Highways & Transportation (UK) Network Management Notes cover a number of traffic management topics and are available for download at http://www.ciht.org.uk/en/knowledge/standards-advice/network-management-notes/index.cfm

The publication "Green and ITS" has a useful chapter on Traffic Management. (See Green and ITS)

ITS and other measures can be applied to control traffic to deal with recurring congestion across urban areas and on regional networks of motorways, freeways, expressways and other arterial roads. The general objective of these measures is to make better use of available capacity through traffic flow improvement strategies, or in many cases by adding extra traffic capacity.

Systems to manage traffic are diverse and can be considered at two levels:

Traffic Control Centres (TCCs) responsible for regional networks have the job of coordinating traffic management on the most heavily trafficked routes. (See Traffic Control Centres) Traffic management at this tactical level involves the implementation of localised schemes, such as ramp metering, automatic incident detection and use of CCTV, supported by the widespread use of VMS. The control systems themselves can be grouped into four categories:

Aside from budgetary considerations, the choice of measures depends largely on the local operating context which covers a spectrum of different operating environments – from high-speed multiple-lane motorways that experience recurring congestion to all-purpose rural 2-lane roads with only seasonal traffic problems.

For a particular section of road the operating environment is determined by a combination of three factors:

The European EasyWay project has developed a classification system for operating environments on the Trans-European Road Network that reflects the level of service expected by road-users, the frequency of recurring congestion and traffic incidents and the feasibility of possible ITS solutions to deal with these problems. It can be used to select the parts of the road network where improvement using traffic management would be beneficial – and for prioritising where to implement different measures. For core (network-wide) ITS services the operating environment classification can be used to prioritise implementation if this has to be done in phases.

Further Information

EasyWay ITS Deployment Guideline ICT-DG01 EasyWay Operating Environments Available for download at: http://dg.easyway-its.eu/DGs2012

Traffic signal control on all-purpose single and dual carriageway arterial roads is frequently used at isolated intersections, often using a demand-responsive control strategy. The installation of traffic signals on any high-speed road demands great attention to traffic safety. Adopting motorway style control and signalling on all-purpose arterial roads is primarily an investment issue: when the need is perceived to be significant the investment budget will be found and the supply base will respond.

As traffic volumes continue to increase, the need to consider areas of the regional network that require special treatment in terms of traffic management will also increase. Sometimes the only tactic during a traffic incident is to keep traffic queuing on the highway to avoid causing much wider disruption. One example is where regional inter-urban routes enter a conurbation, requiring the motorway control systems to be closely integrated with the urban traffic control system. (See Integrated Strategies)

Strategic traffic management is concerned with advising drivers of major incidents and problems so they can adapt journey plans accordingly. Strategic measures are of particular benefit to long-distance traffic and make full use of traveller services – in particular dynamic (traffic responsive) journey planning and en-route information. (See Traveller Services) The network controller’s objective is to balance the flows of traffic on the different routes to the same destination area. A more even distribution of traffic helps reduce congestion and, in the event of a major incident, the ability to respond quickly by diverting traffic away from the affected area. Even a small reduction in demand resulting from advance information can have a dramatic effect on recovery times if it can prevent saturation and flow breakdown.

Advances in technology have made the concept of regional and strategic traffic control more realistic. Strategic traffic management systems are installed to monitor traffic across a regional network of strategic roads where alternative routes exist. These measures provide warnings of serious disruption to traffic with advice and directions on the recommended routes for long-distance traffic.

Network traffic assignment models (such as Motorway CONTRAM in the UK) are sometimes used to decide when to initiate a strategic diversion route. Traffic and travel information systems (VMS, advisory systems and other en-route driver information) are used to advise drivers when there is congestion and delays. (See En-Route Information)

These regional control systems require the interchange of information between local tactical control centres and the strategic regional centres. In Europe several system suppliers offer modular systems that combine urban traffic control and highway traffic functionality to enable local and regional network control.

The trend towards more integrated traffic management will drive greater functional integration of traffic monitoring, traffic information systems and traffic control. Provided there is sufficient spare capacity on the regional network to allow effective strategic re-routeing, network control should significantly reduce delays, increase safety and reduce pollution.

Traffic control covers all measures aimed at distributing and controlling road traffic flows in time and space in order to avoid the onset of incidents or to reduce their impacts. Traffic control is carried out by network operators and controllers with reference to predetermined traffic management policies and plans. In most countries it is an activity done in coordination with the authorities in charge of traffic policing, often under their direct control. (See Traffic Management Plans)

It is possible to distinguish between:

Indirect control measures can be characterised as either preventive action or actions that are remedial or corrective. Indirect control methods are supported by travel information systems. (See Traveller Services)

Preventative action aims to warn drivers of current and forecast problems so they can make adjustments to their travel plans. It may include warning drivers of anticipated problems so that they can change their travel times, choose different routes or abandon their trip. This requires:

Data being generated by ITS field devices and floating vehicles (probes) are valuable resources that provide a foundation for the use of simulation models that can predict congestion and/or journey times. This enables logistics system managers and TCC operators to take action to avoid the onset of congestion—either by diversion or with advice on trip changes.

Remedial or corrective action is designed to limit the extent or impact of delays and congestion that occurs regularly on strategic routes, using measures to limit access and –at a regional level – to divert traffic onto less congested routes. Diversionary routes need to be planned in cooperation with the road authorities and operators of the alternative routes. Often, an alternative high-capacity route will not be available and other options would only be suitable for light traffic – not trucks and heavy goods vehicles. Some road authorities operate seasonal “holiday routes”. Others will only divert traffic when there is a road closure or an emergency (except at ramp meters, where the diversion is indirect).

Remedial action requires:

Closed-Circuit Television (CCTV) coverage of regular “hot spots” for accidents or congestion on the network are an essential part of modern Road Network Operations. Operators in the Traffic Control Centres (TCCs) will scan the CCTV images looking for signs of traffic disruption, such as a smoking vehicle that might break down, debris on the roadway, dangerous or excessive vehicular manoeuvres, or anything that might lead to a traffic incident and congestion. Ongoing developments using image recognition technique are enabling a degree of automation of incident detection. (See CCTV)

Many TCCs do not have sufficient operators to focus on camera scans, even using “camera tours” or “video tours” to monitor a sequence of cameras. More commonly they use system performance measures to alert operators to an incident.

The image below shows an innovative approach used by Florida DOT’s District 4’s TCC in Broward County (USA), in which the entire section of Interstates 95 and 75 can be monitored in its control area on wall projections. It displays the speed profile (average speed) of the traffic on the two interstates, so that operators can quickly identify hot spots. Taking proactive action before a suspected incident occurs is much like preventive maintenance – namely, “Fix the problem before it gets worse.”

System Status Wall Display (Photo courtesy of Florida DOT District 4, used with permission.)

Variable Message Signs are also referred to as Dynamic Message Signs and Changeable Message Signs. A Dynamic Message Sign (DMS) refers to any sign or graphics board where the message (text or pictogram) conveyed to the viewer can change. A DMS may be either a Variable Message Sign (VMS) or Changeable Message Signs (CMS) where:

A Portable Dynamic Message Sign is referred to as a PDMS

Roadside Dynamic Message Signs are the most common way of implementing network control strategies and communicating instructions to drivers. Those that are used on fast arterial roads, motorways and expressways are large constructions, mounted on gantries and positioned over the road. Some are mounted on masts at the side of the road. VMS/CMSs require a power supply and reliable communications between the control centre and the VMS installation.

VMSs provide the means of informing drivers of the need to be aware of approaching conditions. VMSs also have a key role in traffic management at the strategic level as part of a regional control tool. This is the case although VMSs are limited to the display of short messages which – even with pictogram enhancement – cannot convey the same amount of information as is possible via radio and other in-vehicle driver information systems. (See Use of VMS)

Categories of road and traffic situations for which messages can be displayed include:

Many VMSs are placed at strategic locations – for instance shortly before important motorway exits or motorway junctions. This is because at those points a traffic diversion is possible (depending on the message displayed). Sometimes these VMSs are also used at regular intervals along urban arterial roads and motorways, to provide a basic traffic management system – especially on roads that have no lane control systems.

The use of VMSs is, in most cases, coordinated from a Traffic Control Centre (TCC) where a control system will be used to control the display and to monitor the traffic. Where many VMSs are used, it is very important that the operator is able to have a clear overview of all messages displayed. The user interface should also help the operator in setting up, changing and cancelling the messages. (See Human Tasks and Errors)

Some messages will be automatically displayed, without intervention of an operator - for instance travel time indications based on automatically obtained traffic data. Other messages can be planned beforehand – for instance where there are road works or pre-announcements. In these cases the messages can be pre-programmed “off-line”, long before they are used. Some messages, such as those related to sudden incidents or weather circumstances, will need a quick reaction from a traffic operator.

In order to be ready for unpredictable situations, such as road closures in the case of accidents – it is advisable to have pre-prepared (or partly prepared) messages ready to display for all sorts of situations, supported by a control system that can handle these scenarios. In the case of foreseen events, the use of prepared messages can save a lot of operator time and possible confusion. (See Planning and Reporting).

A high level of sophistication is needed for maintaining modern, ITS-based traffic control systems. For example, control systems that require roadside information from detection equipment and/or camera images depend on the ability of the road network operator to install and maintain the systems. (See Vehicles and Roadways) Investment in the ITS infrastructure has to be matched with proper arrangements for equipment installation, communications and maintenance – and an appropriate budget. It may also be necessary to put in place essential administrative systems – for example a fully maintained, up-to-date database of vehicle registration plate numbers and the owner’s details, to be able to make full use of enforcement systems.

A problem experienced in some countries is theft of roadside equipment and related communication cables. Electrical wiring and electronic equipment has value and theft of equipment causes higher operating costs and unreliable incident information. The physical road condition can also impact on the detection systems that can be used. Inductive loops for instance, cannot be installed in pavements that are in a poor condition (potholes and substandard pavement materials). To some extent the move towards ‘non-wired’ systems will open the way for more secure infrastructure deployment.

The potential benefits of a traffic control system must be weighed against the potential cost of installing and maintaining those systems. Countries with economies in transition need to create (or procure under contract) the necessary organisational capability to carry out ITS equipment and software maintenance, to reap the benefits. Rather than rely on advanced systems which may be difficult to maintain and operate, the effective use of less sophisticated methods that use existing facilities may prove more effective. (See Developing ITS Capability and Priority Projects)

Over the years, a wide variety of traffic management systems have been developed for urban traffic control. Some of the more common methods are shown in the display box below. Among them, computerised traffic signal control, also known as Urban Traffic Control (UTC), has become the norm for large towns and cities. In dense urban networks there are clear benefits from using computers to harmonise traffic control to balance demands and flow. Other methods involve the planned management of roadspace through lane assignment, parking controls, turning bans, one-way street systems and tidal flow schemes. The needs of pedestrians, cyclists, the elderly require special attention. (See Safety of Vulnerable Road Users)

The design and management of urban road networks is a vast subject. ITS-related measures have an important part to play.

Computerised UTC systems allow signal plan changing in response to varying traffic conditions. Dynamic control systems have brought substantial benefits, mainly through improvements in mean speeds and reductions in travel time in the range 10% to 20%. They include SCOOT (UK), SCATS (Australia), MOTION (Germany), PRODYN (France), UTOPIA (Italy), and STREAM (Japan). All too often these benefits are quickly eroded by traffic growth with the result that the public may be unaware of the scale of benefit until there is a serious system failure resulting in widespread congestion. (See Urban Traffic Control)

Urban Traffic Control systems have been getting “smarter” by adopting ITS in various ways – for example traffic delay and congestion monitoring, Automatic Incident Detection (AID), knowledge-based control systems and dynamic origin-destination estimation. Improved traffic detection and network monitoring with CCTV, supported in some cases by real-time monitoring of link and network journey times using vehicle tracking and reports from probe vehicles (floating cars). (See Probe Vehicle Monitoring)

A number of other advanced features are also available:

Traffic control strategies are no longer solely about maximising vehicle throughput. They can be designed to achieve deliberate traffic restraint – for example through very high levels of bus priority at the expense of other traffic or by introducing queue management policies and deliberate area access control. These developments, give traffic engineers and network controllers the means to implement a very adaptable form of urban traffic management – that respond to transport policies and management priorities and their acceptability to the public and local politicians.

This involves the use of a lane for different functions at different times of the day- for moving traffic or loading, unloading and parking. For example, Barcelona uses the lane of a busy five-lane artery alternately for moving traffic, parking and delivery of materials during different times of the day.

Permitted use is shown by VMS at the start of the restricted lane and LED Changeable Message Signs (CMS) at intervals along the way to indicate when loading and unloading is active.

Contraflow lanes on urban streets are generally restricted to bicycles, buses and taxis. On high speed arterial roads a contraflow lane may be reserved only for buses or Bus Rapid Transit (BRT).

This strategy applies to traffic that is turning across the opposing traffic stream at a signalised intersection. In the case of countries that drive on the -hand side of the road this mean banning a turn at the intersection. When traffic drives on the , the restrictions apply to -turning traffic. The measure involves taking turning-traffic through the intersection and diverting it in a loop so it can approach the intersection from a different direction. In this way cross-movement is eliminated. Turn restrictions are sometimes supported with VMS if they apply only at certain times of the day.

The restriction of specific movements may bring a shift in traffic patterns and changes to individual movements that are a source annoyance to local residents or businesses. While inconvenient for some – because U-turns, rerouting or other actions are needed – the overall operation of the intersection is greatly enhanced. The inconvenience may be lessened by properly selecting places for U-turns along the corridor or by using a “ground loop” or “jug handle” loop - although this requires turning vehicles to transit the junction twice.

Traffic signal optimisation has been applied to urban networks for many years. The practice of coordinating traffic signals at successive intersections to accommodate the progression of vehicle platoons in a “green wave” is a highly cost-effective method of increasing traffic throughput – reducing delay, stops and fuel consumption. But many traffic control systems run sub-optimally since in most cities signal timings need to be regularly checked to ensure that specific junction timings are optimised to accommodate changing demand patterns.

The purpose of the measure is to adapt the operation of traffic signals to match traffic flows or to impose a specific regulating policy such as bus priority. This may be used at an intersection located:

The procedure consists of:

The use of microscopic simulation models allows quick testing for various strategies at the same time as visualisation of their impact – while verifying quantitatively that various criteria are satisfied. These may include total vehicle time spent on the network or delay time for different categories of users.

Signal plans can be activated in various ways:

Traffic signal control in urban areas should take into consideration the needs of all road users, including pedestrians, two-wheeled vehicles and public transport. This requires:

Adaptive Traffic Signal Control can eliminate the retiming issue and can often achieve greater efficiency, since the systems adjust the traffic signal phase timings cycle by cycle in near real-time – at least for some of the day. Traditional control strategies are still needed for times when the adaptive system fails or becomes untenable. Fixed plans can be useful for traffic gyratories where unexpected demand patterns can cause the gyratory to “lock” in a way that requires a “clearance plan” to return the junction to free flow.

Often when trains, swing-bridges or other modes have priority at traffic signals and block traffic, signal timings at nearby intersections continue as if the blockage had not occurred. Signal timings should be adjusted to accommodate re-routing and VMS be deployed to warn drivers of the delays. Adaptive Traffic Signal Control strategies may be able to react to this situation automatically.

Adaptive Traffic Signal Control is concerned with computerised systems that adapt themselves to actual traffic measurements and situations. They may do so either through the on-line choice of predetermined control plans or through on-line calculation of tailor-made control plans in real-time. Combinations of the two are possible. Adaptive systems measure current traffic conditions and dynamically adjust how much time is allocated to the different traffic streams according to the measured traffic volumes and queue lengths. They:

In saturated conditions, shorter cycle lengths will generally achieve more traffic throughput, because the signals are processing queues at the maximum service rate (called the saturation flow rate) for all movements.

Since adaptive control systems are to some extent “self-optimising,” there is less need to coordinate signal timings in the traditional sense. This is because the signal control algorithms adapt automatically to changes in demand (for example traffic diverted from a motorway incident), eliminating the need for explicit proactive adjustments in the signal timing plans. Developments in recent years allow the use of “gating” strategies that emphasise queue management by controlling the total volume of traffic entering a heavily congested area. These strategies depend on expert systems and dynamic modelling.

As the traffic flow regime changes, the operational objectives and priorities may change as well. For example, as traffic demand increases the level of service drops until saturation flows are reached and congestion sets in. During this transition, the control objective may change from free flow, to maximising vehicular throughput and finally to queue management.

For urban arterial networks, “gating” strategies can be applied to store queues of vehicles where they do the least damage. These strategies provide a way for determining where queuing traffic should be held to cause least disruption, so that traffic flows freely within the gated area. It is also necessary to minimise the impact that queuing traffic may have through “blocking back” which affects upstream intersections.

More sophisticated urban traffic control systems will take account of traffic parameters such as queue lengths at junctions, point-to-point travel times and traffic delays. These can be measured using ITS-based techniques such as automatic video queue length measurements, automatic video license plate readings and probe vehicle data.

It is important to understand that even fully adaptive systems are generally not completely autonomous. Competent control room staff with experience of traffic management are still needed to deal with complex situations whenever they arise. Sometimes better progression can be achieved using traditional offline optimisation routines than the automated systems offer. Furthermore, no traffic signal system is able to deal successfully with oversaturated traffic conditions.

As traffic control efficiency reaches its practical limit, further benefits in urban travel management will come mostly from the development of demand management policies inducing modal and time shifts (such as controlled access to urban areas, teleworking and car sharing). (See Demand Management)

Modern UTC systems generally include priority management of public transport and emergency vehicles – and increasingly, traveller information systems such as park-and-ride directions, parking occupancy, arrival time of the next bus. (See Information Dissemination)

This concept of traffic signal pre-emption uses sensors and/or transponders to detect public transport vehicles (trams or buses) approaching an intersection and special control software to either:

This is also a demand management strategy – to encourage the use of public transport – and has been shown not to interfere with other traffic unreasonably, so improving overall throughput. (See Transport Demand Management)

The centre lanes on urban arterial roads are sometimes used for moving traffic in one direction in the morning and the opposite direction in the afternoon. For example Barcelona in Spain, uses reversible lanes, referred to as “tidal flow,” on three of seven lanes of a major artery – which are controlled by VMSs on overhead gantries. Birmingham (UK) has a similar arrangement on the Aston Expressway. In other cities the centre lanes have been reserved for express public transport during peak periods. Cross-traffic turns are usually prohibited when this use is active but permitted off-peak – again controlled by overhead lane control signals.

These systems are put into operation on a daily basis during peak periods where there is recurrent congestion with available capacity in the opposite direction (one lane minimum) . Sometimes this involves the use of special equipment to move the central safety barrier. Many tidal flow schemes simply use signing systems such as variable lane assignment signs placed on gantries. For practical reasons, the lane direction changing is generally made on a fixed-time basis (each day at predetermined hours), although several cities in the United States have implemented a concept that allows more dynamic reversal of lane directions.

A number of different control methods are applied on regional networks of motorways, freeways, expressways and other arterial roads. Their aim is to enhance or increase capacity and/or stabilise the traffic flow and prevent the onset of stop/start conditions. Flow stability also has a beneficial effect on traffic throughput. The methods include:

Regional traffic control and management systems most commonly communicate with drivers via VMS. These usually comprise two or three rows of characters to form a message. Often, these are augmented with lane control signs and in some countries, with pictograms.

At the tactical level VMS provides the means of informing drivers of the need to be aware of approaching conditions. VMS also has a key role at the strategic level as part of a regional control tool. VMSs are limited to the display of short messages – and even with pictogram enhancement cannot convey the amount of information that is possible using radio, social media and in-vehicle driver information systems.

EasyWay ITS Deployment Guideline VMS-DG01 Principles of VMS Design available for download at: http://dg.easyway-its.eu/DGs2012

Ramp metering is a form of tactical management widely used in North America. It is used to a lesser extent in Europe and the rest of the world due to the practical problems of comparatively short motorway on-ramps with limited queuing capacity. Detection is needed on the freeway or motorway both upstream and downstream of the merge point. Merging traffic is held on the ramp to be released at a rate typically controlled by the volume of through traffic on the main carriageway.

Ramp meters reduce the likelihood of flow breakdown by preventing traffic levels on the main carriageway reaching unstable levels. Once flows become unstable and stop-start conditions set in, there is a significant loss of capacity and queues develop on the motorway due to the volume of traffic. The aim of ramp metering is to prevent or delay the onset of flow breakdown, to maximise throughput. One goal of metering is to encourage diversion of short-distance trips off the motorway. This is achieved by:

Ramp metering is implemented by installing traffic signals on the on-ramps to regulate the flow of traffic joining the motorway during peak or congested periods. The signals control the discharge of vehicles from the on-ramp, holding back the merging traffic and breaking up platoons of vehicles as required. It is important to have sufficient capacity for queuing vehicles so that the adjacent motorways and access roads are not disrupted by queuing traffic waiting to merge.

Timing of on-ramp traffic signals is generally dependent on the prevailing traffic conditions on both the main carriageway and the on-ramp. Access can be regulated in isolation (each ramp regulated independently) or centralised, with the flows admitted at consecutive ramps being computed by a comprehensive traffic management system. The system requires:

In practice, ramp metering systems are located upstream of recurrent bottleneck congestion points – and have a safety role in addition to relieving main-line congestion. Ramp meters may be deployed individually or in combination as a dynamic system.

Most of the ramp metering systems that have been deployed are based on demand/capacity or occupancy rate algorithms and are not coordinated on an area-wide basis. More sophisticated systems account for conditions over a long section of the motorway, not just at the individual interchanges. One co-ordinated solution (ALINEA in France, for the Paris ring road and Île-de-France motorways) consists of imposing target downstream occupancy rates on the motorway for each of the local metering systems. The set of occupancy rates are optimised at the area-wide level.

Ramp metering systems have proved to be a very effective way of maintaining good levels of service for traffic on the motorway, at the expense of those vehicles waiting to enter. This can be regarded as paying a small “time toll” in order to enjoy the benefits of a relatively free-flowing motorway. By spacing out the merging traffic, there is less queuing in the acceleration lane and smoother merges, which permits more stable flow and increases overall throughput. Motorway mainline speeds may be increased by as much as 50%. There is a disbenefit to traffic queuing on the ramp but the delay incurred at the signal is offset by the benefits to mainline traffic, both upstream and downstream where the merging traffic is included. More advanced ramp metering algorithms are even more effective.

Ramp metering is not deployed to directly deter drivers making short trips but can have the added benefit that it may discourage drivers who do make short trips – from using the motorway network when suitable alternatives exist.

EasyWay ITS Deployment Guideline TMS-DG03 Ramp Metering Available for download at: http://dg.easyway-its.eu/DGs2012

The purpose here is to adapt the use of available running lanes to traffic circumstances. This most often involves handling recurring gridlock on a section of road linked to insufficient capacity of the section, or gridlock when one or more lanes are unavailable. This measure covers the following areas of use:

Examples of specific uses include:

The introduction of lane control requires resources such as automated controls to verify the consistency of instructions provided by various lane assignment signals, a modular barrier, or temporary marking (cones or beacons).

Regardless of the method used, the operation may be cumbersome and complex. All control systems must be maintained in fail-safe condition. For example:

Managed lanes are either newly-built lanes or existing High-Occupancy Vehicle (HOV) lanes that are converted to High-Occupancy Toll (HOT) lanes. These operate as toll lanes using Electronic Toll Collection (ETC) or Open Road Tolling (ORT). The toll is applied to Single-Occupant Vehicles (SOVs) and in some cases low-occupant vehicles. Carpools (car-sharing by two or more occupants) generally can use the HOT lanes without charge to encourage greater use of HOVs. Single-occupancy vehicles are charged a variable toll that is dependent on the time of day, level of congestion on general-use lanes and the occupancy of the HOT lanes. Shifting demand from the general-use lanes to the HOT lanes makes better use of the available capacity in the HOT lanes while improving flow for all.

Narrow lanes, hard shoulder running and contra-flow systems often operate during construction, maintenance, widening and reconstruction of motorways. They have become commonplace on the motorway network and often create serious bottlenecks which require tactical measures to warn of delays ahead. Mobile generator-powered VMSs are often used to give warning of disruption and display average journey times. Speed controls, often with camera enforcement, are used to minimise accident risk and smooth flows.

An HGV Overtaking ban is a means to channel trucks and HGVs onto a single lane (the slow lane). Implementation of a HGV overtaking ban is one of the measures allowing traffic managers and road operators to improve smooth running of traffic during peak periods. This traffic control measure can improve the co-existence of heavy goods vehicles, light vans and private cars on networks with high levels of traffic.

Its objectives are to:

EasyWay ITS Deployment Guideline TMS-DG06 HGV Overtaking Ban available for download at: http://dg.easyway-its.eu/DGs2012

Dynamic lane management enables the flexible allocation of traffic lanes, which can be modified by means of Variable Message Signs, traffic guidance panels, permanent light signals, multiple-faced signs, LED road markers, and closing and directing installations. Fundamental applications of this service are: tidal flow systems, lane allocation at intersections, lane allocation at tunnels.

Dynamic reversal of lane direction can be made with systems using gantries but should always be subject to the operator’s validation. The implementation of the tidal flow remotely by the operator, can be eased by the use of video cameras (close the lane, wait until no car remains in it, then open it in the opposite direction).

Having reversible, tidal flow or contraflow lanes on a motorway – or having an entirely separate, reversible roadway – permits otherwise unused capacity in the off-peak direction to be used in the peak direction of flow. ITS can facilitate its operation through use of VMS, lane control signals, remote-controlled gates, CCTV and sensors. Reversible roadways in a number of US cities and in Barcelona in Spain have proved very effective. A motorway “tidal flow” system leading in to Birmingham in the UK has been in operation for over 30 years.

To add capacity during peak periods, moveable barriers can be deployed. Functionally, this is similar to contraflow, but instead of shifting traffic to the other side of a median, the median itself is moved. This effectively adds a lane to the peak direction. Lane control signals and Portable Dynamic Message Signs (PDMSs) can help with this technique, although the added lanes are usually separated by normal pavement lane lines and the movable barrier.

EasyWay ITS Deployment Guideline TMS-DG01 Dynamic Lane Management available for download at: http://dg.easyway-its.eu/DGs2012

Hard-shoulder running enables temporary use of a motorway hard shoulder with the aim to increase road capacity when necessary. The name comes from motorway shoulder lanes used in emergencies - which originally had a relatively weak pavement but are upgraded and “hardened” to take running traffic. The goal of hard-shoulder running is to increase traffic flow to minimise or prevent heavy congestion and reduce the probability of congestion-related incidents.

Hard-shoulder running is similar to the creation of an extra lane, but have specific safety issues when vehicles stop when a breakdown occurs. It adds capacity whilst safety is maintained by ITS devices such as CCTV with image processing to detect a stationary vehicle, lane control signals and VMS. Safe refuge areas are normally provided for vehicles needing to stop when the hard shoulder is open to traffic.

Hard Shoulder Running can be at fixed times, or triggered automatically by traffic demand, or initiated by manual request from the control room operator. The measure can be applied to bottlenecks, locations with poor safety records (black spots) and recurring lack of capacity during peak periods. Some authorities allow buses and, in some cases, general (mixed) traffic to use the shoulder lane during peak periods.

The illustrations below shows the hard-running shoulder on I-66 in Fairfax County, Virginia, USA – and a close-up of the sign and lane control signal.

Hard-Running Shoulder on I-66 USA

Hard-Running Shoulder on I-66

EasyWay ITS Deployment Guideline TMS-DG04 Hard Shoulder Running available for download at: http://dg.easyway-its.eu/DGs2012

Although different from other highway control methods, the control of commercial vehicles, especially freight vehicles, can be an important part of traffic control. A freight control system will typically use GPS and mobile phones to manage the exact location of a vehicle and its freight at any given time. By extending this system, it can help to control the traffic by routeing the freight to a less congested route.

Driving difficulties for trucks and HGVs during snow for example, may lead to traffic congestion on the whole network. A possible solution may be to organise HGVs in convoys. This type of action requires:

EasyWay ITS Deployment Guideline TMS-DG06 HGV Overtaking Ban available for download at: http://dg.easyway-its.eu/DGs2012

The common objective of speed controls is to encourage drivers to travel at a safe speed or to improve traffic flow. They are a means to help drivers to travel at an appropriate, consistent speed taking account of the prevailing traffic or weather conditions. Persuading drivers to adopt more realistic speeds can have a calming effect and reduce erratic lane changing. The smoother traffic flow permits more throughput. In some cases these systems are also used to mitigate environmental effects, such as pollution or noise.

The measures are usually applied to sections of motorway that experience recurring congestion with gridlock and stop-start traffic conditions, including sudden stops that can be a source of accidents. It works:

Apart from handling recurring periods of congestion, speed regulation is a tool that can be used in all traffic conditions to gradually slow vehicles approaching a traffic incident or accident area.

Speed control systems are more common in Europe than in the USA or Japan. The major benefits relate to traffic smoothing, with improved throughput and a reduced rate of accidents. Displayed speeds are generally mandatory, rather than advisory - and enforced by speed cameras. They are aimed at reducing the range of individual speeds in non-congested situations and protecting the end of queues when congestion appears. In some systems the variable speed limit display is coupled with an automated enforcement system involving video cameras recording licence plate numbers, which issues citations to motorists who exceed the speed limit by a predetermined threshold. (See Enforcement)

The major benefits of speed control are improved safety and better journey times. Smoother traffic flow yields a slight increase in capacity, and a reduction in the number of accidents, especially rear-end accidents. Capacity effects are small and unable to solve bottleneck congestion – but in sections where demand approaches capacity, speed control is likely to delay the onset of stop-start conditions. In some cases, depending on highway conditions and capacity limitations, traffic flow breakdown may be prevented. These benefits are obtained by reducing the speed differential between vehicles and engaging driver attention.

This measure requires:

Traffic monitoring is indispensable: the operation can be fully automated but an operator must be able to recover control at any time if an unexpected event occurs – such as an accident or sudden deterioration in weather conditions. This measure is particularly suited to urban and suburban motorways, where the high proportion of routine drivers facilitates user compliance. The short length of controlled roadway (typically about 10 kilometres) also promotes adherence to speed limits.

EasyWay ITS Deployment Guideline TIS-DG04 Speed Limit Information available for download at: http://dg.easyway-its.eu/DGs2012

US Federal Highways Administration Engineering Speed Limits available for download at: http://safety.fhwa.dot.gov/speedmgt/eng_spd_lmts/

Speed limits that are legally enforceable may require the use of special VMS that closely resembles the official speed-limit sign mounted on overhead gantries. They can be supported by speed enforcement systems that use camera images to identify speeding vehicles and drivers. For some legal jurisdictions the approved VMS may need to be authorised in legislation in order to be enforceable.

Speed control is often associated with lane control because both measures generally use the same display equipment (gantries and signs). It can also be used for incident management or traffic control through work zones.

A similar effect may be achieved through variable speed advisory signs, which do not have to be legislatively enabled or enforced, although such signs may have lower levels of compliance. Motorists may claim confusion over the mixture of regulatory (fixed) and advisory (VMS) speeds.

The success of VSL requires that drivers understand, and comply with, the reasons behind changing the speed limit and the associated benefits. In most cases, the displayed speed limit should match the conditions that drivers encounter. There will be some cases when circumstances call for a reduced speed limit for which the reason is not obvious – for example environmental reasons, or problems downstream such as incidents or work zones. A study in the UK showed that when a reason is displayed on VMS alongside the speed restriction, there was a 20% increase in driver compliance with the restriction.

EasyWay ITS Deployment Guideline TMS-DG02 Variable Speed Limits available for download at: http://dg.easyway-its.eu/DGs2012

US Federal Highways Administration Variable Speed Limits available for download at: http://safety.fhwa.dot.gov/speedmgt/vslimits/

Controlled Motorways involve the application of several Automated Traffic Management techniques in combination – such as mandatory Variable Speed Limits (VSL), measures to reduce the frequency of lane switching through messages such as “Stay in lane”, speed controls and other traffic calming measures. In some systems (for example, in UK on the motorway around London and Birmingham), the variable speed limit display is coupled with an automated enforcement system (involving video cameras recording licence plate numbers), which issues citations to motorists exceeding the speed limit by a predetermined threshold.

Dowling R.G and Elias A. Active Traffic Management for Arterials - A Synthesis of Highway Practice NCHRP Synthesis 447 Transportation Research Board , Washington D.C. USA, 2013 download at http://onlinepubs.trb.org/onlinepubs/nchrp/nchrp_syn_447.pdf

Federal Highways Administration Active Traffic Management available for download at: http://ops.fhwa.dot.gov/atdm/approaches/atm.htm

EasyWay ITS Deployment Guideline TMS-DG04 Hard Shoulder Running available for download at: http://dg.easyway-its.eu/DGs2012

UK Government gateway to information on Managed Motorways / Smart Motorways available for download at: https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/smart-motorways

Although the situation may vary between different jurisdictions, the enforcement of traffic regulations often becomes relevant to the operations of the network. To ensure a smooth network flow, road users are expected to comply with regulations. Unless those regulations are self-enforcing (for example speed control through traffic calming measures) there needs to be a way to enforce the regulations.

Enforcement is not new – but recent technological advances have enabled new methods of automatic enforcement. The use of digital imaging and image processing, such as automatic licence plate recognition has had a dramatic impact.

Enforcement methods using new technology involve some kind of automatic detection. Sensors and digital cameras make it possible to better detect offences in speeding, red light violations and other evasions. The role of applying penalties is generally undertaken by an organisation responsible for enforcement (usually the police). The biggest benefit of these monitoring systems is said to be their deterrent effect. Enforcement systems are unpopular but will generally cause most users to become more cautious – increasing safety and improving the general throughput of the network. (See Policing / Enforcement and Law Enforcement)

One of the most frequent uses of automatic enforcement is the enforcement of speed limits using speed cameras. This requires a specialised speed camera that will measure the speed of each vehicle. In many cases, the system simply displays the speed to bring it to the driver’s attention, which is often enough to encourage them to reduce speed. In other situations, the system will take a picture of the offending vehicle for follow-up action. This would usually include capturing the number-plate of the car – but in some cases, it is necessary to include the picture of the driver, since in many countries, the vehicle owner may not be liable for actions by someone else using the vehicle.

The speed enforcement system can be permanent or a mobile unit. The information acquired by it will be used by the enforcement agency to apply penalties or (if necessary) prosecute the offender. Point-to-point journey times can be monitored by installing two cameras that are linked. Average speed monitoring is now commonplace, especially to regulate traffic speeds over extended sections, such as work zones. (See Speed Management)

Red light evasion ("red light running") at traffic signals can lead to serious accidents and it is extremely important that the traffic lights are observed. If non-compliance is high police presence or automated camera enforcement are two options. Automatic systems use a speed sensor (inductive loop) embedded in the road and a camera installed under the traffic signals. The red light and the vehicle sensor together will activate the camera and a picture taken of the offending vehicle. More advanced systems use the camera both to detect violations and to photograph the offence.

Where a railway (railroad) crosses a road or highway at a level crossing (“at-grade" crossing) there is always a potential safety issue. The level of protection varies considerably between different countries and regions. Where they are protected by gates, flashing lights or barriers – there is often in addition enforcement systems aimed at improving safety. For example, rather like red light traffic signal evasion, if a road vehicle enters a rail intersection during a warning period, it will be photographed.

ITS technologies are being explored to develop systems which can detect potential road/rail vehicle conflicts and help prevent collisions. For example, an Australian team is trialling an in-vehicle collision alert system which uses GPS and Dedicated Short Range Communications (DSRC) to warn vehicles if a train is approaching a crossing.

Heavy vehicles (trucks in particular) are often driven continuously by a single driver, accidents often result from fatigue. In many countries, there are regulations that specify the maximum amount of continuous driving time that is permitted. In order to enforce this, a black-box or electronic tachograph that detects the axle movement and possibly the location of the vehicle along time is often used. (See Driver Safety)

Since the road can only take a certain amount of weight per axle, it is important to ensure that all vehicles are not overloaded and are within legal limits. Otherwise, there will be significant deterioration of the road structure. Weigh-in-Motion (WiM) systems use a sensor on the road to measure each vehicle’s axle weight. When an overloaded vehicle passes, it will be notified to the enforcement agency which will take appropriate measures. (See Weight Screening)

Since most of violations may be contested in court, the systems must be adapted to meet the legal requirements of each country. In some cases, only the vehicle number-plate (licence plate) is necessary to catch the offending vehicle, while in others, the actual driver must be identified. For these systems to be effective and have the desired deterrent effect, they need to collect information that can stand up in court. Equipment must be type approved to certify that it operates to the required standard of accuracy and reliability. Type approval is important to avoid a legal challenge based on inadequate equipment and procedures. (See Equipment Certification)

Privacy is another important issue. It is extremely important to keep records confidential. In the case of identifying and notifying offenders, it may be necessary to capture photographs of offenders, which may lead to privacy concerns. (See Privacy)

One of the most difficult issues in implementation is proper coordination between the enforcement agency and the road network operator. In many countries, the road operators do not have the power to enforce regulations (this is usually police work). It is important to establish good working relations with the traffic police, to ensure that enforcement activities will facilitate better operation of the network.

Until a decade ago urban and motorway traffic control systems were considered separately – both from a technical and institutional perspective. As traffic demand increases the need for a seamless transition between systems becomes more important. The need for integration is particularly acute in situations where there are heavily trafficked motorways, expressways and parallel arterial road routes. The demand for reliable real-time driver information systems continues to grow. Increasingly the control of traffic on urban streets can no longer be treated separately from highway traffic control.

The Integrated Corridor Management (ICM) concept is one of the most significant developments in integrating ITS functions and resources between different organisations. Motorway and all-purpose arterial roads operations are closely coordinated from a single Traffic Control Centre (TCC) – or a highly integrated (linked) set of two or more TCCs. The objective is to achieve an overall balance of traffic between routes that serve a common set of destinations. This involves balancing demand through signal control and pro-active use of driver information, coupled with traffic diversions in some cases.

Integrated Corridor Management is designed to operate the motorways and the arterial road network and to optimise the use of both. It applies especially to a corridor with similar travel routes, that are broadly in parallel, serving similar destinations. Ideally, a single TCC would manage traffic on both motorways and the arterial roads, so that operators can shift resources – and demand – from one roadway to the other as conditions require.

An alternative to a single TCC, is to integrate several local TCCs by sharing data, images, information and decision making. Their managers will need Traffic Management Plans and Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) that address balancing traffic along the corridor and managing traffic when an incident occurs. (See TCC Administration and Traffic Management Plans) Closely integrated operations are particularly beneficial in managing planned special events where the road traffic uses both the all-purpose arterial roads and motorways.

Public transport (transit) management is often an important element of network control – where for instance one or more bus and/or multimodal rapid transit stations are located within the managed corridor. In general though, purely transport operations (such as vehicle dispatch) are managed from a separate public transport operations centre. (See Operations & Fleet Management)

Freight customs clearance demonstrates the use of ITS in selected corridors. This could be a road freight or heavy goods corridor or a trans-continental or country-to-country corridor such as Mexico to Canada (via the USA) or Nicaragua to Panama (via Costa Rica). (See Freight Enforcement)

Planned events have a significant impact on Road Network Operations. They include sporting events, concerts, festivals and conventions taking place in permanent multi-use venues (for example – arenas, stadiums, racetracks, fairgrounds, amphitheatres and convention centres). There also include less frequent public events such as parades, fireworks displays, bicycle races, sporting games, motorcycle rallies, seasonal festivals and milestone celebrations at temporary venues.

Five categories of special events can be identified based on their characteristics:

These are all different forms of traffic incident and often require major planning for traffic management, preparation and response. They are distinct from other incident types in a number of important respects – one being that they involve a new set of stakeholders that do not play a part in most other types of incidents and emergencies. They include:

Planned Special Events can have a significant impact on travel safety, mobility and journey time reliability across all the transport modes and roadway facilities. Managing travel for these events involves:

Events such as the London Olympic Games require considerable planning. Traffic lanes dedicated to vehicles carrying competitors to their events were introduced, a command and control centre was established and additional roadside hardware was deployed (mainly VMS and vehicle detection equipment) – (See Case Study: London 2012 Olympics)

The practice of managing travel for Planned Special Events should target the following objectives:

The goals of managing traffic and travel for these events are as follows:

Traffic Incident Management (TIM) is the response to traffic accidents, incidents and other unplanned events that occur on the road network, often in potentially dangerous situations. The objective is to handle incidents safely and quickly, to prevent further accidents and restore traffic conditions back to normal as quickly as possible. It requires the deployment of a systematic, planned and coordinated set of response actions and resources.

Traffic Incident Management proceeds through a cycle of phases starting with immediate notice of possible dangers or problems ahead – as soon as an incident occurs – in order to forewarn drivers and prevent accidents.

Incident warning and management have two main goals – to:

Incident management requires planning, a response that is proportionate, safety at the scene of the incident and recovery. It requires attention to three main aspects – in order of priority – safety, mobility of traffic flow and control and repair of damage.

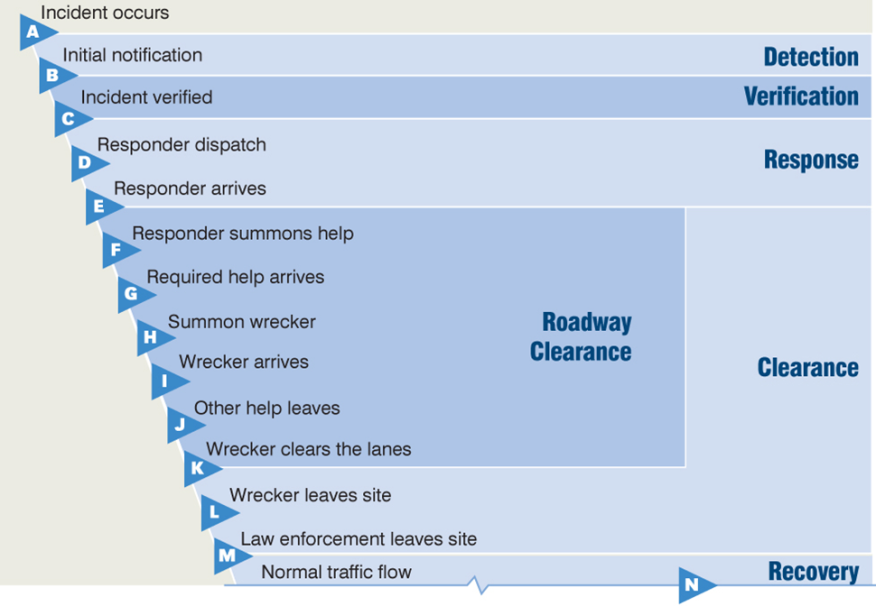

To understand how control strategies and network operations can reduce the negative impact of incidents, it is important to understand the timeline and different stages of incidents, as shown in the diagram below.

Timeline for a Typical Traffic Incident - Source: Wallace, et al., 2007/2009 - Note: “wrecker” is an American term used to refer to “recovery vehicle or team” or “breakdown truck or tow-truck provider”.

The diagram might represent a collision on a motorway, a spill of materials or a disabled vehicle - resulting in the need to close one or more of the running lanes. All steps will not occur in every incident - and there may be other interwoven relationships – but the diagram represents the typical sequence for most moderate-to-serious incidents. The steps are shown in a staggered fashion simply to illustrate that the incident timeline is not uniform (the time increments are relative – and not to any scale).

The duration of particular stages in the incident are represented by the letter pairs in the diagram and are listed below. For example, the duration of the incident itself would be from point A on the timeline to point M, while the total time the incident is having an effect on traffic is from A to N – with the time elapsed to point N often proportionately much longer than shown.

Common phases of an incident are:

Although not evident in the diagram, the recovery period is frequently longer than the duration of the incident itself. Incident recovery can be four-to-five times longer. This means that for every minute that can be trimmed off incident detection, verification and/or clearance, up to 5 minutes of recovery time can be saved for traffic to get back to normal.

Avoiding secondary incidents is of paramount importance because they start the incident response cycle all over again. The aerial photograph below illustrates this point. The original incident that caused the multiple vehicle pile-up was a car that was stationary due to its engine overheating – which blocked a traffic lane in the direction going “downstream”. The stationary vehicle was the cause of one or two collisions but many more collisions on both sides of the highway occurred because a vehicle responding to the incident attempted to bypass the traffic queue and reach the incident by travelling the wrong way on the opposite side. The example shows that secondary incidents can in fact be more serious than the original incident.

Secondary crashes resulting from a "wrong-way" (contra-flow) response - Source: Wallace, et al., 2007/2009, originally from the collection of John O’Laughlin.

All agencies must work closely together to quickly detect an incident, and to verify, respond and clear it in as timely and efficient a manner as possible. ITS in general and the Traffic Control Centres (TCCs) in particular will play a part at each stage. (See Urban Operations and Highway Operations) The emphasis must be on the rigorous application of the 4-Cs of incident management (Communication, Cooperation, Coordination and Consensus) and close inter-agency working, through Traffic Incident Management (TIM) teams. Traffic Incident Management Teams and Safety Service Patrols are vital elements of a good traffic incident management programme. (See Incident Response Plans)

Clarity in assigning roles and responsibilities to the Traffic Incident Management (TIM) Team, the Mobile Safety Service Patrols and tow-truck providers during traffic incidents cannot be understated. Even though the TIM team may not be an active participant in the response to a particular incident, it has a key role to play in formulating the policies, practices and training that go into it. TIM members will include the first-line responders or organisations that provide direct support. Mobile Safety Service patrols and tow providers are also active participants. (See Mobile Patrols)

Typical use of ITS devices and the roles and responsibilities of the TCC and Mobile Safety Service Patrols are summarised in the two tables below for different stages of an incident. In these tables there is no implied sequence of actions within cells – instead they are typical actions that might be taken.

|

|

Roles and Responsibilities |

||

|

Incident Stage |

Use of ITS |

Traffic Control Centre |

Mobile Safety Service Patrol |

|

Detection |

|

|

|

|

Verification |

|

|

|

|

Response |

|

|

|

|

|

Roles and Responsibilities |

||

|

Incident Stage |

Use of ITS |

Traffic Control Centre |

Mobile Safety Service Patrol |

|

Roadway Clearance |

|

|

|

|

Incident Scene Clearance |

|

|

|

|

Recovery |

|

|

|

|

After Action |

|

|

|

Protection of personnel and field equipment from vehicle impact is of primary importance during any traffic incident or on-road emergency. Use of high-visibility vests or uniforms by incident response teams and maintenance workers should be mandatory. High-visibility markings on response vehicles and maintenance trucks helps to avoid collisions. Buffer zones around incidents or maintenance work create a safety zone – although care needs to be taken to balance safety with keeping roadway capacity available for traffic flow. Standard practice differs considerably from country to country and local practices should be followed where they exist.

All means of travel and traffic information can be used to provide timely and accurate information to travellers about the nature and location of incidents and maintenance activities (See Travel Information Systems). Automatic Incident Detection can support queue protection warnings to the approaching vehicles up-stream (See Automatic Incident Detection).

Several innovative initiatives have been used in Europe and South America, as follows:

The responders’ first priority must be the safety of themselves and the people involved in an incident. Incident scene management, particularly on high-speed roadways, often involves closures of lanes and discussions about when to re-open lanes to allow traffic to pass an active incident scene.

Creation of a Safe Zone around the incident. Courtesy Georgia DOT.

These decisions will be made by the incident controller (commander), who has powers to control and direct traffic (usually the police, highway or traffic patrol). ITS can assist with the decision making process. CCTV camera images – or the transfer of information from them – can be delivered to the commander either verbally or visually via tablet computer or a wireless mobile device – giving a “higher-level” view of surrounding conditions than available from the ground. Traffic and Travel Information is provided to inform drivers about lane closure status – enabling them to make more informed choices about making diversions or delaying or rerouting a trip. Less traffic helps ensure the safety of responders. (See Travel Information Systems)

Mobile Safety Service patrols play a vital role in safety. They help to manage the scene and alerting drivers who are approaching the back of the queue, help avoid secondary incidents as well as alerting passing drivers – improving the safety of the responders at the scene. VMS, Portable Dynamic Message Signs (in particular those mounted on Safety Service patrols) and other driver information delivery systems can help in providing a safe incident scene and protecting responders engaged directly in incident recovery. (See Use of VMS)

Many of the urban high-speed toll roads in South America have near total coverage by CCTV. This allows the TCC staff to monitor and record the entire response effort. These videos can later be used as a valuable training tool. CCTV also enables TCC staff to monitor upstream traffic to warn of any developing situations or to inform about secondary situations as they develop. (See CCTV)

It is sometimes difficult to determine whether a situation on the road will deteriorate into a major traffic incident or even a full-blown emergency. Some operational tasks for incident management described here may appear disproportionate to the number of incidents that occur. The crisis management checklists developed by the planning teams will help to optimise service, time and efficiency when an emergency occurs. If the impact of the incident is widespread several control centres may become involved in responding – and coordinated action will be needed. (See Incident Response Plans and Emergency Plans)

Work zones - due to road, bridge and tunnel construction and maintenance work have a negative impact on Road Network Operations. ITS and other techniques are used to minimise the negative impacts and keep traffic moving through affected zones as efficiently and safely as possible, for both for travellers and workers. This is especially important for night-time work, which is becoming increasingly common on the highways.

A number of measures are used to minimise worker exposure to motorised traffic and to safeguard road users from the construction and maintenance work. They include:

Safety cannot be achieved by preventive measures alone. It is important to constantly monitor the traffic situation, weather conditions and the specific construction or maintenance activities taking place – and respond as necessary. This can be achieved through the establishment of an integrated traffic management and construction operations centre. Often a dedicated operations centre with tow-trucks for incident response is set up.

In safe and stable traffic flow, traffic lanes must be observed so that proper segregation between vehicles of different speed is maintained. This can be done through the use of road studs, "cats eyes" or some other physical markers in the lane separation – which the driver will sense if the vehicle strays into a neighbouring lane. This may either trigger a warning or – in vehicles with advanced equipment – a warning could automatically lead to corrective action by the vehicle itself. Cameras or lasers, can be used to sense vehicle intrusion into closed lanes, which could otherwise endanger workers. (See Warning and Control)

ITS technologies provide many opportunities for monitoring and managing work zone operations – but are not a way of saving on fixed signing and traffic cones. ITS has benefits when signing and coning in preparation for roadworks – and when the roadworks are live and an incident occurs. A reliable source of power will be required, such as a portable generator.

ITS applications have been used to measure spot speeds in work zones. More recently APNR cameras are widely used to support average speed enforcement – with good compliance. Other ITS technologies are used to collect data that accurately reflects travel conditions through work zones – and, more recently, real-time monitoring of traffic conditions.

Use of ITS in work zones is not limited to urban areas. Temporary ITS devices, such as Portable Dynamic Message Signs (PDMS), Highway Advisory Radio (HAR), trailer-mounted cameras and sensors – can easily be deployed in a rural work zone where permanent ITS does not exist. Several commercial companies provide services that may include these devices, which communicate their data and images to a remote location where they are monitored (along with images from other locations). If issues arise, those monitoring the cameras can contact local law enforcement and transport officials who are able to respond.

In summary, ITS technology can be applied in work zones for the purposes of:

Many applications serve a combination of these purposes to:

Some regions have automated enforcement in work zones. The data and information necessary to support enforcement action can be collected from the use of Bluetooth, CCTV cameras, buying third party data and coordination with the TCC.

Most work zones are relatively short-term in nature, but some maintenance and construction work is long-term. Early deployment of ITS can be effective in supporting diversions, managing incidents and mitigating capacity reductions.

So-called “smart” work zones employ a combination of data sources to measure journey times through the work zones and are becoming commonplace in many countries. Real-time ITS supports a wide array of innovative applications that include active management of work zones based on observed traffic conditions. These capabilities are used to extend work hours and maintain acceptable journey times. Work is curtailed when journey times exceed certain thresholds. Work zone managers can be warned when travel speeds are dangerously high and a police presence may be needed.

In the UK work zone contractors have to limit their possession of the roadway for maintenance work during peak times. One innovative solution to this involves the use of Portable Dynamic Message Signs (PDMS) - with built-in traffic detection to monitor traffic demand. The ITS equipment allows the contractor to maintain lane restrictions longer – until the volume of traffic requires them to be removed. The increased time for site occupation allows longer work periods, improving productivity so that the works finished sooner. Motorists benefit from a reduction in the overall period of disruption.

Most emergencies are characterised as “short” or “no-warning” incidents or events, such as sudden major storms or other severe weather events, airline or train crashes, earthquakes, flash floods or terrorist threats. The less frequent, but usually more devastating events are “with-warning” emergencies, such as a hurricane, tsunami, tidal wave, flash flood, major river flood or spreading wild fire. The response to these different levels of emergency can be very different.

Having days to prepare for something like a hurricane or flood allows agencies to alert the public in a timely way, to stockpile or reposition resources, to muster additional resources and ultimately, prepare for evacuation. Emergency managers and responders can be more proactive in their responses.

When the warning is short, or non-existent, the response is almost entirely reactive. This is why Emergency Management protocols require extensive planning, preparation and training. Transport agencies are advised to be more involved in development of Emergency Operations Plans. (See Emergency Plans)

There are two aspects of primary concern:

When the transport system itself in not materially impacted – by a pandemic for example – the transport network becomes the focus of responding agencies. Roadways, public transport, trains, boats, ships and airplanes become the means of avoiding or evacuating from the emergency.

For traffic operations, transport managers can take the following actions to assist emergency managers:

When the transport network is directly impacted by the emergency it will be less effective in serving the emergency and its managers. This is where emergency pre-planning and preparation within the transport agency are so important.

In the USA, the Florida DOT and several coastal urban areas in this hurricane-prone state, stockpile traffic signals and generators in order to be able to replace damaged signals and to control restored signals in the absence of commercial power. Portable Dynamic Message Signs (PDMS) can temporarily replace damaged VMSs. Temporary Highway Advisory Radio units can be used for a similar purpose – but need to be supplemented by fixed signage that informs travellers of the HAR station frequency.

Effective communications is essential between Traffic Control Centres, Emergency Operations Centres and other centres where data and information about the emergency is collated (“Fusion Centres”) but not always fully achieved. Often it is because of differences in the jurisdictions of different transport agencies, emergency mangers and security people. Law Enforcement Dispatch Centres and Emergency Call Centres (999) can be included in the mix. In some regions this problem is exacerbated by the lack of open, non-proprietary communications protocols.

All can be connected by telephone and the Internet but co-location or direct electronic linkages for data, camera images and information sharing is more effective.

Extreme emergencies might require evacuation of residents and visitors, sometimes from large areas. Because of their extreme nature, a region can never be fully prepared to meet all of the challenges – both physical and institutional – that arise. From a traffic perspective, any evacuation is going to severely threaten the capacity of the transport network to handle it. Most of the actions that agencies can take to mitigate the negative impact of an evacuation and help keep traffic flowing require changes in the physical infrastructure or the use of mass-passenger modes.

Public transport (transit), school buses and trains can be used to transport evacuees, particularly those that are mobility-challenged – such as patients in hospitals and other health-care facilities, students, the homeless and prisoners. These arrangements take time to organise and carry out, and require good inter-agency cooperation. ITS can assist to a some extent – for instance by giving bus drivers the same traveller information that other vehicle occupants receive.

In urban areas, entire city streets can be shifted to one-way operation to accommodate large numbers of vehicles escaping harm’s way. These require large numbers of police or military officials to control traffic. ITS does not have a significant role here, other than to minimise the conflicting guidance that traffic signals might indicate (such as green displays in the “wrong" direction).

These can be deployed effectively to use the inbound capacity for outbound evacuating traffic. Emergency contra-flow lanes are often in rural areas. ITS can contribute through VMSs to reinforce contra-flow guidance, CCTV to monitor the traffic - and the provision of travel information to inform travellers. Most public information will be generated by the incident command centre. The increasing use of probe vehicles can give transport and emergency managers data on journey times.

In a few instances, devices such as motorway ramp-closure gates can be deployed for use in contra-flow operations. Normally motorway entrance ramps have to be closed to traffic.

The photograph shows a contraflow operation in Houston, Texas before Hurricane Rita in 2005. Contraflow requires a great deal of advanced planning, physical preparation (such as the cross-over lanes), large teams of officials for implementation, and time to deploy and later restore to normal. A number of USA states on the Gulf and Southeast Atlantic coasts - as far north as Baltimore – have Contraflow Plans, but most regard the measure as a last resort.

Courtesy Texas DOT.

Security threats are not very different to natural emergencies – except that they can have a broader range of impacts, such as cyber/Information Technology (IT) attacks, Chemical, Biological, Radiological, Nuclear and Explosive (CBRNE) threats and other terrorist actions. (See Network Security)