Road Network Operations

& Intelligent Transport Systems

A guide for practitioners!

Road Network Operations

& Intelligent Transport Systems

A guide for practitioners!

With the growth in deployment of ITS and the information and communication options available to drivers, the modern car has been described as ‘a SmartPhone on wheels’. Information may be presented both in-vehicle and externally and needs to be relevant, timely, consistent and useful. The challenge for designers – supported by standards and guidelines – is to provide the information and services demanded by drivers that are usable without causing unsafe distraction and overload. In-vehicle human factors have a number of important consequences for Road Network Operations, in particular:

As well as information and entertainment, in-vehicle sensor, communications and processing technology can assist drivers by providing advice and warnings concerning the vehicle’s immediate environment. These warnings have to be perceived, understood as relevant, and acted upon appropriately if they are to be effective. Guidelines in this area are now emerging.

Driver error is consistently identified as a contributory factor in over 90% of vehicle crashes. Better design of the driver interface has the potential to keep the driver “in-the-loop” whilst increasing safety. Additionally, many vehicles now include ITS that provide automation of specific elements of the driving task. Systems can even be designed to intervene in vehicle control to avoid or mitigate an impending collision. Nevertheless, usability issues around how the vehicle ‘feels’ and responds, and how control is partitioned between the vehicle and the driver, are crucial to achieving driver trust, acceptance and adoption. The RESPONSE Code of Practice provides at least some guidelines in this emerging area and further research is underway.

It is good practice for new ITS vehicle applications or in-vehicle information and communication products to be simulated and trialled with users to understand better the interaction between them and any consequences

There are many international regulations on vehicle design and many standards and guidelines relating to information and communication systems (ICT) and warning and assistance systems.

A considerable volume of international regulation exists in relation to design requirements for motor vehicles that aim to ensure that technology within vehicles can be used safely. The United Nations Economic Commission for Europe’s (UNECE) Transport Division provides secretariat services to the World Forum for Harmonization of Vehicle Regulations (WP.29). The World Forum provides the regulatory framework for technological innovations in vehicles to make them safer and to improve their environmental performance. There is also a range of international law that affects drivers’ interaction with their vehicles and ITS. In Europe these take the form of Directives from the European Commission. In the US, there are both national and state laws on ITS human factors issues such as hand-held phone use and texting while driving.

Although not legally binding, international standards provide process, design and performance advice. The following are the main international working groups in areas relevant to vehicle design and usability:

Much of the knowledge from these standards has been incorporated in design guidelines and codes of practice. (See ITS Standards)

The European Commission (EC) has supported the development of a document called the ‘European Statement of Principles on HMI’ (referred to as ESoP) which provides high-level HMI design advice (EC 2008). As an EC Recommendation it has the status of a recommended practice or Code of Practice for use in Europe. It also contains 16 Recommendations for Safe Use (RSU), which build on Health and Safety legislation by emphasising the responsibility of organisations that employ drivers to attend to HMI aspects of their workplace. Adherence to the RSU is likely to promote greater acceptance of technology by drivers.

The design guidelines of the ESoP comprise 34 principles to ensure safe operation whilst driving. These are grouped into the following areas: Overall Design Principles, Installation Principles, Information Principles, Interactions with Controls and Displays Principles, System Behaviour Principles and Information about the System Principles.

The US motor vehicle manufacturers have developed ‘Alliance Guidelines’ that cover similar, high-level, design principles as the ESoP. The Guidelines (Auto Alliance 2006) consist of 24 principles organised into five groups: Installation Principles, Information Presentation Principles, Principles on Interactions with Displays/Controls, System Behaviour Principles, and Principles on Information about the System.

The USA’s National Highway Transportation Safety Administration (NHTSA) has worked with automobile manufacturers and the mobile phone industry to develop a set of guidelines for visual-manual interfaces for in-vehicle technologies. These are based on the ESoP/Alliance guidelines and introduce some specific assessment procedures (NHTSA 2013). The NHTSA also plan to publish guidelines for portable devices and guidelines for voice interfaces.

The Japanese Auto Manufacturers Association’s (JAMA) Guidelines consist of four basic principles and 25 specific requirements that apply to the driver interface of each device to ensure safe operation whilst driving. Specific requirements are grouped into the following areas: Installation of Display Systems, Functions of Display Systems, Display System Operation While Vehicle in Motion, and Presentation of Information to Users. Additionally, there are three annexes: Display Monitor Location, Content and Display of Visual Information While Vehicle in Motion, and Operation of Display Monitors While Vehicle in Motion.

Guidelines on establishing requirements for high-priority warning signals have been under development for more than five years by the UNECE/WP29/ITS Informal Group (Warning Guidelines 2011). There has also been work in standardisation groups to identify how to prioritise warnings when multiple messages need to be presented – and one ‘Technical specification’ (TS) has been produced:

In addition, two Technical Reports are relevant that contain a mixture of general guidance information (where supported by technical consensus) and discussion of areas for further research:

To help promote driver acceptance of Advanced Driver Assistance Systems (ADAS), a key issue is ensuring controllability. This has been addressed through guidelines. Controllability is determined by:

Drivers will expect controllability to exist in all their interactions with assistance systems:

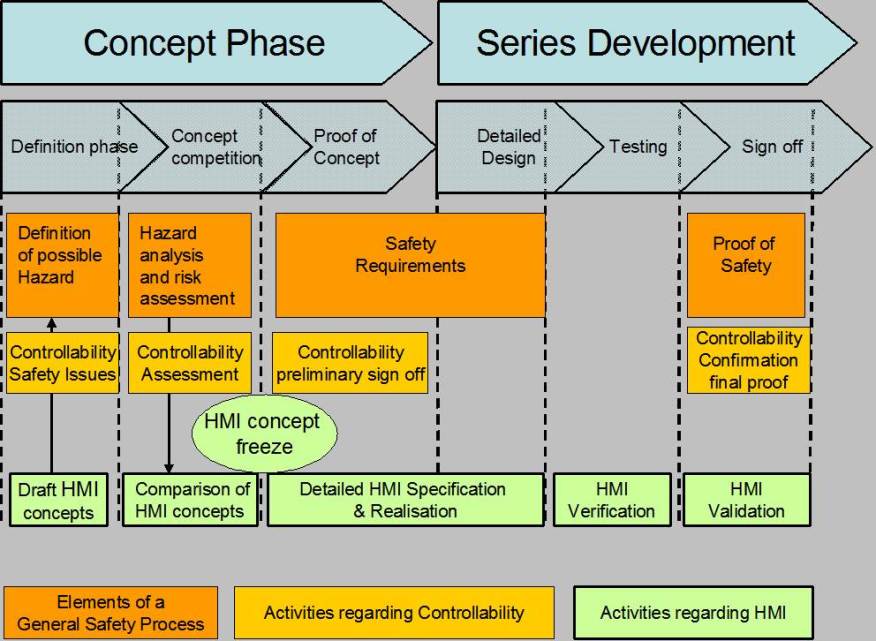

The European project RESPONSE, has developed a Code of Practice for defining, designing and validating ADAS. The Code (outlined in the figure below) describes current procedures used by the vehicle industry to develop safe ADAS with particular emphasis on the human factors requirements for ‘controllability’.

Another European project, ADVISORS has tried to integrate the RESPONSE Code within a wider framework of user-centred design taking account of the usability of information, warning and assistance systems. The Intelligent Transport Systems (IHRA-ITS) Working Group of the International Harmonized Research Activities – is developing a set of high-level principles for the design of driver assistance systems (IHRA-ITS 2012).