Road Network Operations

& Intelligent Transport Systems

A guide for practitioners!

Road Network Operations

& Intelligent Transport Systems

A guide for practitioners!

Designing an ITS product, system or service for the people who will use it is not simply a case of designing to a required specification for a ‘standard’ person, as there is no such thing as a standard person – everyone is different. Whilst people possess certain qualities and limitations that apply, at least in part, to everyone, they are by no means universal. For example, it is possible to quantify reasonable upper limits for human visual performance – but some people cannot see anything at all, others may have blurred vision, and for those who see in sharp detail there may still be issues such as colour blindness affecting their vision. Some differences between people are innate and last a lifetime, some may come and go, whereas some may develop slowly over time. Whatever the reason, differences between individuals must be accounted for in any design, and this includes ITS.

Whilst human variability is vast in scale, there are certain key areas that are likely to influence ITS practitioners in their work.

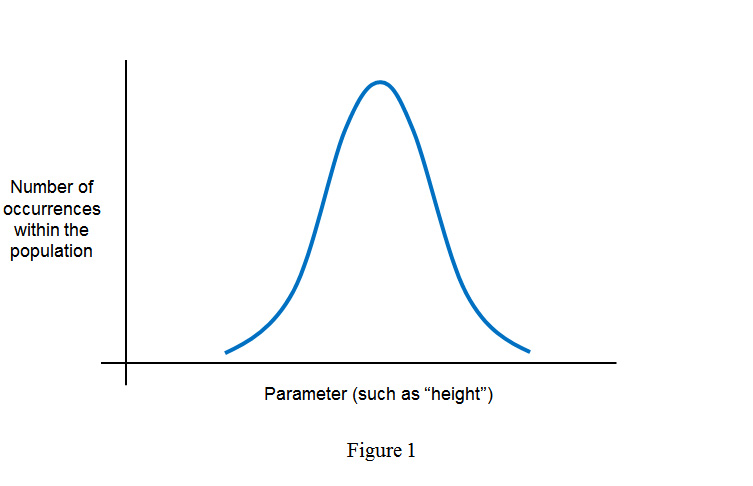

The vast majority of quantifiable human attributes (especially physical characteristics) follow what is known as the ‘normal’ distribution. This is a distribution seen throughout nature and is represented in the figure below. It shows that the average value within a population (for a criteria such as height) will be the most common, with more extreme (large or small) values being progressively less common. There is no such thing as an average person as there is almost certainly nobody alive that is exactly average in every conceivable parameter. Instead the population is comprised of individuals who may be higher up the distribution on some parameters and lower down the distribution on others.

It is unavoidable that as people age their senses and faculties start to deteriorate. Eyesight and hearing are amongst the most prominent in terms of the senses, but mobility will also usually be affected – and at some point most people will begin to experience a slowdown in their speed of mental processing. The ability to learn new skills quickly will also reduce over time. The converse of this is that the faculties of younger road users may still be developing. Basic senses in younger people may be well functioning, but cognitive abilities may not yet be at adult levels, which can impair decision-making. Younger users will also typically be smaller and less physically developed than adults.

Differences based on social and cultural background can sometimes be pronounced – and although generally harder to quantify than age-related decline, their impacts can be predicted at some level. Key considerations in ITS will relate to factors such as attitudes towards different road users, acceptance of technology and driving conventions. For example, cyclists and car drivers often experience confrontation based on different perceptions of each other. General attitudes of different user groups can often be determined by engaging with relevant users, to understand and help predict and take account of potential conflicts – whether they be within user groups, between user groups, or between users and technology.

Four high-level principles help guide those working with ITS:

If someone was to design a door it would clearly be foolish to use an average person’s height to determine the door height – since it would not be usable by at least half of potential users. Instead the door should be designed to accommodate the tallest users as there are no detrimental effects for shorter users. In the same way, when designing an overhead gantry-mounted variable message (VMS) information screen, the text should not be at a font readable only by those with 20:20 (average) vision. By making the text larger, a greater proportion of road users are taken into account and the text is easier to read by all.

There may be times when it is not possible to accommodate everyone at the same time. In such cases, the principle of designing for the 5th-95th percentiles of the population is generally adopted. If, for example, someone was designing a forward/back seat adjustment mechanism for a car – a key parameter will be the leg-length of users. If all users were ranked according to leg length:

Adopting the 5th– 95th percentile principle means that the seat is made adjustable so as to be used comfortably by the middle 90% of users in terms of leg-length. If it is possible to design a seat that is practical and can accommodate the 1st– 99th percentiles, this would be even better.

Given the importance of creating an open and useable road transport system for all, traffic planners, engineers and designers should seek to accommodate the full range of users wherever possible. If not, consideration must be given to how those whose needs have not been taken into account will be affected – and whether these consequential effects are acceptable. An entirely different solution may be needed.

If the principles outlined above are applied and an effective design is established for one application, it may not be the case that this can simply be transferred to other applications. An example could be a system that has been implemented successfully in one country and is being considered for use in another country. Cultural differences between users or technical differences in the transport infrastructure may mean that users interact with the system in a different way – and that there are unintended effects that had not previously been identified in the original application. Variability may also be an issue where a system is already established. Changes in user populations can happen over time and changing external factors may alter the overall operation of the system. Whenever updating or introducing a new system, it is useful to conduct user testing.

The following universal aspects of human variability should always be taken into account in the design and operation of any facility or service that will affect road transport systems: