Road Network Operations

& Intelligent Transport Systems

A guide for practitioners!

Road Network Operations

& Intelligent Transport Systems

A guide for practitioners!

A Heavy Goods Vehicle (HGV) is more likely to travel longer distances than a light goods vehicle – in some cases crossing borders and travelling through countries to reach distant customers. Tolling of heavy goods vehicles is aimed at regulating their use of roads. It helps ensure that HGVs pay a contribution towards the cost of providing and maintaining the road infrastructure they use – even if vehicles are registered in other countries. Taxes and charges are most commonly levied on the basis of distances travelled and annual permits. Its deployment may be limited to a strategic road network or apply to all roads.

The first use of taxing HGVs for distance travelled, was in New Zealand in 1975. Since then, the practical implementation of regulating HGVs use of roads by means of taxes and charges has evolved significantly and can be based on route and time of travel as well as distance travelled. The requirements for accuracy of charging and the enforceability of schemes have evolved to the point that HGV charging is now a proven ITS application – technically and operationally.

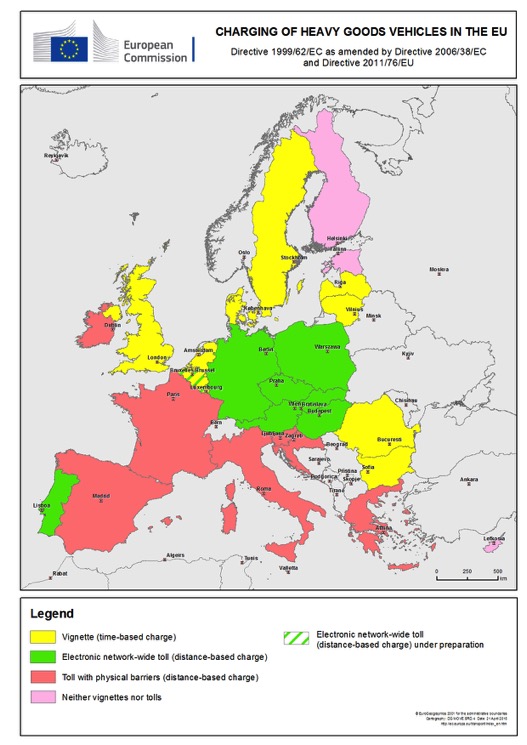

Globally, the densest networks of actively regulated HGVs are in the European Union – as illustrated in the figure below. This includes the UK, where the HGV levy was introduced in April 2014. Elsewhere in Europe, Switzerland and Norway have implemented schemes – and there are other examples in Australia, North America and sub-Saharan Africa. Transit nations such as Austria, Germany, Namibia and Switzerland have developed their own regulations based on some mix of road types, time and distance, with variations of charges depending on emissions class of the vehicle.

HGV tolling does not depend on the existence of a general ETC tolling regime for all vehicles – but can make use of it.

Most commonly, an HGV tolling policy is stand-alone (such as in Austria, Germany, Namibia and Switzerland) – but where part of the road network already imposes tolls on all vehicles, HGV tolling can be integrated into a general tolling policy (such as in the USA). The tolling policy defines the operational strategy and technology requirements. In all cases, there needs to be:

HGV tolling can be achieved by:

The relatively low cost of tags and roadside identification systems suits an HGV scheme that has a very limited number of roads or border crossings (See Methods of Payment). On Board Units (OBUs), able to determine vehicle location via Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS) allow an HGV tolling scheme to be deployed on a much larger road network and enable differentiation of charges according to type of road or other factors.

The vehicle location technologies used in ETC also support other objectives – such as the management of HGVs conveying hazardous materials (‘Hazmat’), fleet management, cross-border pre-clearance, cabotage regulation, and detection and enforcement of overweight vehicles (See Freight and Commercial Services).

Charges may also vary according to a HGV’s emission class or other factors. Examples include:

The starting point of some of the HGV charging schemes (for example, Switzerland, Germany and the Czech Republic) was a paper ‘vignette’ (a time-based permit) that was displayed in the windscreen of vehicles that used the main road network. The labels are designed to be checked manually but some are not very secure since they can be modified or forged. The UK scheme uses the vehicle’s number plate to check whether a vignette has been paid (recorded on a central database) – rather than a paper sticker. Alternatively:

A back office is needed to manage the database of HGVs and enforcement operations (See Back Office/Enforcement). If charges are not related to usage, an annual charge can be levied on all HGVs (for example, the UK’s HGV Levy). Compliant vehicles can be confirmed by comparing vehicle number plates with a centrally held database of vehicles and payments made.

The cost and time to register HGVs for tolling should not be underestimated. It is recommended that sufficient vehicles are registered before HGV tolling commences – to reduce the initial strain on the enforcement operations. Compliance checking may always require some combination of mobile inspectors and unmanned, static roadside systems. Static systems can operate at lower cost with higher accuracy on busy roads compared with manual checks. Occasional users may be able to register manually for every trip (such as in Germany).

HGV tolling exists in many forms – from vignettes to GNSS-based schemes with static enforcement and mobile inspection teams. All European HGV tolling schemes that have migrated from a vignette system to HGV tolling have chosen DSRC, GNSS or some combination of these, supported by fixed and mobile enforcement. The unit cost of a GNSS-based OBU is higher than an RFID or DSRC tag – but the initial cost must be weighed against the cost of operations and the number and type of roads to be tolled.

Migration is feasible:

The adoption of standards or harmonisation of systems provides flexibility for migration – particularly in relation to the format of vehicle number plates and account details from tags and GNSS-based OBUs. Periodic monitoring of new technologies (and standards) to help plan for the long-term, is recommended.

Cross-border HGV movements bring their own challenges:

Various solutions exist:

NZ Transport Agency, 2013. Road User Charges, NZ Transport Agency, New Zealand Government

Swiss Federal Department of Finance (Switzerland): http://www.ezv.admin.ch/zollinfo_firmen/04020/04204/04208/

German LKW Maut scheme operator: http://www.toll-collect.de

Transport for London (UK): www.tfl.gov.uk/lez

Port of Los Angeles: http://www.portoflosangeles.org/ctp/ctp_portcheck.asp

Road Fund Administration (Namibia): http://www.rfanam.com.na

Pickford A. and Blythe P. (2006) Road User Charging and Electronic Toll Collection, Ch2, Artech House, Boston (USA) and London (UK)

New Zealand Government. Road User Charges Act, 1977.