El requisito fundamental de los Sistemas Inteligentes de Transporte son los datos y la información acerca de la red de transporte (rutas y autopistas). Los datos deben ser confiables, actuales, legibles, accesibles y los suficientemente exhaustivos para propósitos de planificación y operación. Ésto es la “info-estructura” de la cual dependen muchas aplicaciones ITS. Los datos básicos están usualmente georreferenciados y mantenidos en formato digital tal como una base de datos de enlaces entre caminos que conectan sitios conocidos o nodos sobre la red - cada uno con una única referencia. (Ver Procedimientos de Planificación)

Como mínimo, la información de la red consistirá en un “nomenclador" (o índice) que mantiene los códigos y breves descripciones de los enlaces viales, nodos y otras sitios, tales como:

Un nomenclador de la red puede proveer una base para la base de datos de navegación si es lo suficientemente detallado. (Ver Navegación y Posicionamiento)

El tipo de inventario requerido para el equipamiento y activos ITS implementados a lo largo de una red será determinado, en gran medida, por los requerimientos operacionales locales y por las aplicaciones ITS a ser mantenidas y soportadas. La información acerca del equipamiento ITS y su localización requerirá alguna forma de sistema de gestión de datos y un método apropiado de localización georrefrencial para asistir a la representación espacial de la información. Los Sistemas de Gestión del Mantenimiento (MMS) y los Sistemas de Gestión de las Comunicaciones (CMS) son bases de datos relacionales que pueden ser utilizadas para mantener un inventario de equipamiento ITS y la infraestructura asociada de comunicaciones. Algunas veces, se incluyen un sistema de monitoreo de la performance y/o un sistema de detección de fallas. Éstos monitorean aspectos críticos de la performance de equipamientos o de sistemas y emiten alertas al contratista de mantenimiento cuando se detectan fallas. Estos equipamientos de supervisión pueden del tipo de Unidades Remotas de Monitoreo (OMUs) o de Sistemas de Monitoreo de Performance (PMS).

Partiendo de la base de la descripción de la red y utilizando cualquier sistema de localización referencial, una multiplicidad de datos contribuirá a la base de inteligencia para las Operaciones de la Red Vial. Ellos incluyen, para cada enlace vial:

La base de inteligencia vial necesita ser mantenida en tiempo real y actualizada, teniendo en cuenta cualquier modificación insignificante a la red vial, la cual puede ser:

Donde las operaciones viales sean bien desarrolladas, una exhaustiva base de datos servirá para prever el impacto sobre la capacidad de la red ante futuros eventos. Ésto requerirá consultas con los grupos clave de interés tales como las autoridades locales y los servicios de emergencias. (Ver Planificación e Informes)

Otras capas de información de la red vial serán generadas por los sistemas de monitoreo del tránsito. Los datos provenientes del monitoreo del tránsito tienen tres funciones principales en las operaciones de la red vial:

Estas funciones básicas serán desempeñadas por la información disponible desde una variedad de fuentes y será necesario un enfoque sistemático del monitoreo del tránsito. Un enfoque planificado y ordenado es esencial, especialmente si los datos serán utilizados para:

Los sistemas automáticos de monitoreo del tránsito proveerán datos en tiempo real de volúmenes y velocidades vehiculares, tiempos de viaje punto a punto y, en algunos casos, clasificación de vehículos. Estos datos necesitan tener una referencia temporal y ser almacenados con una alusión al(los) enlace(s) con los cuales están relacionados, en conjunto con el registro de la fuente de datos. (See Tránsito & Monitoreo de Estado)

Los modelos computarizados de la red vial son utilizados para diagnosticar futuras condiciones del tránsito y predecir tiempos de viaje. La modelización hace uso de datos de las características de los enlaces, capcidades de las intersecciones y si los datos de tránsito y relativos a incidentes están disponibles – los cuales pueden ser dinámicos en tiempo real o históricos. Las estimaciones del modelo pueden ser comparadas con los resultados del monitoreo del tránsito para asistir a su calibración y validación. Un modelo de red puede también ser usado para diagnosticar los efectos de una dada estrategia de gestión del tránsito e identificar los beneficios potenciales de esa estrategia comparada con el escenario de "no hacer nada" o con un plan de respuesta alternativo. La modelización puede también realizar evaluaciones de riesgos o puebas de sensibilidad alrededor de difrenetes planes de respuesta.

La modelización de la red es capaz de entregar una gestión estratégica del tránsito más eficiente mediante la validación de la toma de decisiones y mediante la provisión de mejor información para objetivos de planificación de la gestión de la red vial. También puede ayudar a proveer mejor información de viaje a los usuarios del camino, tales como más precisos tiempos de viaje y diagnósticos de las condiciones del tránsito. (See Modelos de Tránsito)

Diferentes métodos son utilizados para proveer información de la localización dependiente de la tecnología que esté disponible y la precisión requerida. Muchos países han establecido un sistema nacional de referencia en red el cual necesita ser interpretado para dar las coordenadas de latitud y longitud globales. Ejemplos de localización referencial incluyen el posicionamiento global y el Canal de Mensajes de Tránsito del Sistema Radial de Datos (RDS-TMC).

Posicionamiento Global (Latitud/Longitud)

Los Sistemas de Posicionamiento Global (GPS) proveen un medio para la determinación de la localización de un objeto, en términos de latitud y longitud, basados en señales recibidas desde múltiples Sistemas Automáticos de Navegación Satelital (GNSS) – por ejemplo, los satélites GPS a los sitios de los receptores GPS. Además de la localización, el GPS puede ser utilizado para seguir vehículos y puede proveer una gestión económica de flotas y un monitoreo del itinerario de un vehículo a lo largo de su ruta.

Canal de Mensajes de Tránsito del Sistema Radial de Datos (RDS-TMC)

Algunos países – mayoritariamente en Europa – han invertido en la localización referencial vía radio digital, conocido como el Canal de Mensajes de Tránsito (Traffic Message Channel - TMC). Usando la tecnología del RDS-TMC sólo 16 bits datos (la unidad más pequeña de datos en computación) son asignados a una codificación de localización. Ésto significa que las tablas de código de localización RDS-TMC están solamente disponibles para referenciar uniones significativas de autopistas (nodos) y longitudes viales. (enlaces). (Ver http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Traffic_message_channel)

Los sistemas ITS típicamente usan múltiples servidores para las diferentes aplicaciones, estaciones de trabajo y pantallas de video en centros de control de tránsito. El hardware juega un rol principal en cualquier sistema ITS. Es responsable por:

En cuanto al hardware, algunas aplicaciones ITS (tales como los sistemas de gestión de incidentes y de autopistas) típicamente incluyen pantallas gráficas en el centro de control para proveer una descripción visual de las operaciones de los sistemas de transporte, capturadas por las videocámaras en el campo.

Los gráficos pueden verse en los monitores de la estaciones de trabajo de la sala de control o en grandes pantallas en la forma de un video wall. Estas pantallas proveen una ventana principal ( o vista) del sistema de gestión de tránsito – y están usualmente basadas en una representación gráfica o mapa de la red de autopistas. Ellas muestran los activos disponibles para el monitoreo de la red y el control del tránsito, tales como las señales y los VMS´s, y la localización de los Teléfonos Viales de Emergencia (ERTs o Postes SOS) y las videocámaras CCTV.

Software and relational databases are required for ITS technologies to store, manage and archive network data. These are brought together as Archived Data Management Systems (ADMS) or what is sometimes called ITS Data Warehouses. ADMS offers an opportunity to take full advantage of the travel-related data collected by ITS devices in improving transport operations, planning and decision-making at minimal additional cost.

The technologies supporting ADMS are designed to archive, fuse, organise and analyse ITS data and can support a wide range of very useful applications such as:

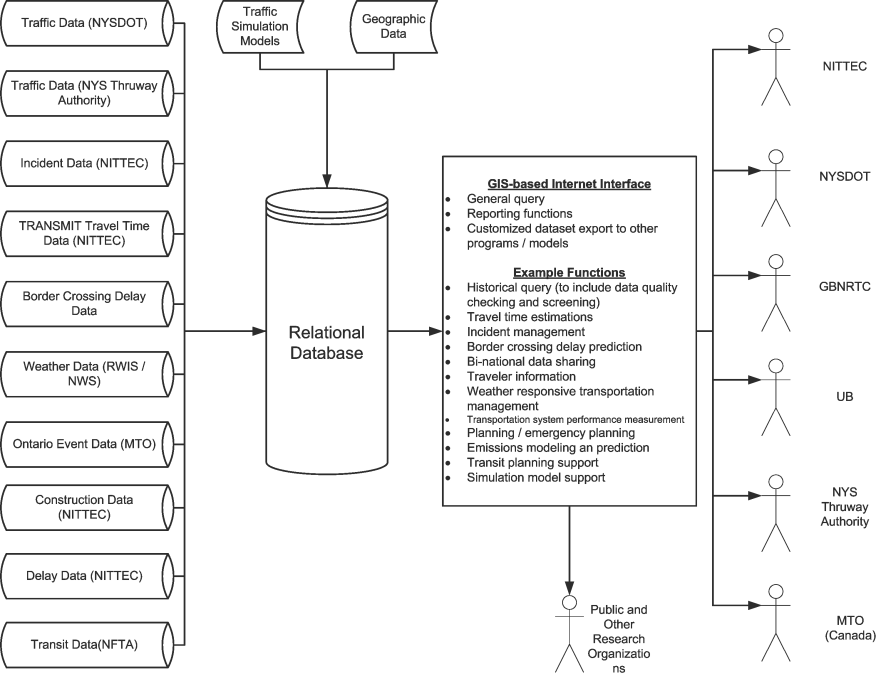

The figure below shows an example of the system architecture designed for a simple ITS Data Warehouse being developed for the Buffalo-Niagara region in New York State USA. At the core of the system is a relational data base (such as Oracle or MySQL) which receives data from a wide range of sources including real-time traffic data (volumes, occupancies and speed), incident information, travel time and delay information, weather data, construction and work-zone information, and transit data (such as automatic vehicle location data). The relational database organises and fuses the data and information together – linking the different data streams through common identifiers – allowing a wide range of applications to be developed and deployed.

System architecture designed for a simple ITS Data Warehouse (Buffalo-Niagara Region New York State USA)

Among the data stored in ADMS are transport system inventory data, which can be used to facilitate the construction of detailed network models and traffic simulation models. Every link and associated junction in the network will need to be classified according to its strategic importance and capacity. Many ADMS are provided with functionalities that can convert the stored data into the required format for running different traffic simulation and analysis software.

A key benefit of having an ADMS is the ability to quantify network conditions in terms of travel times, speeds and traffic volumes. These measures, based on real-time traffic data, can be used to provide dynamic status information of prevailing network conditions and the “level of service” offered to road-users. Historical data of this kind, including information for incident detection and management and for traffic modelling, can also provide the basis for traffic forecasting and predictive information.

Tree-building algorithms:

Almost all ADMS now include a web-based graphical interface to support users’ queries. The interface is commonly based on Geographic Information Systems (GIS) technology. GIS comprise a set of computer software, hardware, data, and personnel – that store, manipulate, analyse, and present geographically referenced (or spatial) data. GIS can link spatial information on maps (such as roadway alignment) with attribute or tabular data. For example, a GIS-digital map of a road network would be linked to an attribute table that stores information about each road section on the network. This information could include items such as the section ID number, length of section, number of lanes, condition of the pavement surface, or average daily traffic volume. By accessing a specific road segment, a complete array of relevant attribute data becomes available.

The Graphical User Interface (GUI) shown in the ADMS architecture diagram above shows that the data archived in the ADMS can be accessed by different stakeholders over the Internet. Custom applications and reporting functions may be designed including performance measurement, predictive traveller information, traffic simulation model development support, and many other applications.

One of the primary functions of a road or highway network is to allow the safe passage of people and goods from their origin to their destination. Traditional sources of information (printed road maps, direction signs, route listings and journey plans) all have their place but satellite navigation systems are now used widely. Generically these are known as Global Navigation and Satellite Systems (GNSS). Specifically, they include the Global Positioning System (GPS) developed by USA, GLONASS, the Russian global satellite navigation system and GALILEO, the civilian global satellite navigation system being developed by the European Union from its precursor, the European Geostationary Navigation Overlay Service (EGNOS) (See Video).

The USA’s GPS consists of 24 satellites that are deployed and maintained by the US Department of Defence (USDoD). Originally, the system was used solely for military purposes, but since 1983 the USA has made GPS available for civilian purposes. For location determination (longitude, latitude, and elevation), a GPS receiver needs to receive signals from at least four satellites (signals from the fourth satellite are needed to correct for errors and improve accuracy).

A GPS on-board a vehicle – or a smart-phone with a GPS – can determine the location of the vehicle. The location can then be communicated via wireless communication to a central location (such as a traffic operations centre) for processing and data fusion. Besides pinpointing the location of a vehicle and communicating that location to a traffic operations centre, GPS receivers are at the core of all navigation-aid devices developed by companies such as Garmin, TomTom, and Magellan. For navigation and turn-by-turn directions, accurate digital maps are needed, in addition to the GPS receiver.

For its operation, the USA’s GPS relies on signals transmitted from the 24 satellites orbiting the earth at an altitude of 20,200 km. GPS receivers determine the location of a specific point by determining the time it takes for electromagnetic signals to travel from the satellites to the GPS receiver. A limitation of GPS is that it cannot transmit underground or underwater and signals can be significantly degraded or unavailable in urban canyons, in road tunnels and during solar storms. This is why there is continuing interest in terrestrial based radio-positioning systems using technologies such as mobile phones, Bluetooth and Wi-Fi.

GALILEO is the first complete civil positioning system to be developed under civilian control, in contrast to the USA’s GPS and the Russian Glonass systems. GALILEO has been designed with commercial and safety-critical applications in mind, such as self-guided automated cars. The first satellite was launched on 21 October 2011 and the system is scheduled to be fully operational before 2020. When fully deployed GALILEO will consist of 30 satellites (27 operational plus 3 back-up), circling the earth at an orbit altitude of 23,222 km. GALILEO will be fully interoperable with GPS and GLONASS and is expected to achieve very high levels of service reliability and real-time positioning accuracy not previously achieved.

![Figure 3: The European Galileo satellite constellation [European Space Agency] Figure 3: The European Galileo satellite constellation [European Space Agency]](/sites/rno/files/public/wysiwyg/import/intelligent-transport-systems/1439558854html_html_m763d5216.jpg)

Figure 3: The European Galileo satellite constellation [European Space Agency]

Digital maps are a pre-requisite for satellite navigation and many other ITS applications, such as automated driving and traveller information systems. Many technologies are currently available for creating and updating digital maps. For example, digital maps can be created by collecting raw network data, digitising paper maps, from aerial photographs and other sources. An initiative called OpenStreetMap (http://www.openstreetmap.org) intends to develop digital mapping for the whole world. The maps are developed from GPS traces collected by ordinary people and uploaded to the website. Aerial imagery and low-tech field maps are often used to verify that the resulting maps are accurate and up to date.

A navigation database is a commercially developed database used in satellite navigation systems. It is often based on a Network Gazetteer (See Infoestructura Básica) and will contain all the elements needed to construct a travel plan or a route from a specific origin to a specific destination. Additional criteria may be added such as the route passes through a specific point, that it avoids tolls, that it is the fastest or shortest available, or that it minimises fuel consumption or emissions.

A navigation database is multi-layered and requires more than the basic coordinates for the road network links and nodes, although that is an important starting point.

Additional features necessary for navigation include:

Navigation databases also contain information on points of interest and landmarks, such as public transport facilities, major office buildings by name, hotels, restaurants and tourist attractions, post offices, government buildings, military bases, hospitals, schools, petrol stations, convenience stores, shopping centres and malls, toll-booths – and in some countries, the location of speed cameras.

Crowd-sourcing and social networking has enabled the creation of navigation databases that are adapted to the needs of specific groups of road-users, such as truck drivers and cyclists. There are also important developments taking place in pedestrian navigation.

Infromation on pedestrian navigation: Financiación and http://www.navipedia.net/index.php/Pedestrian_Navigation

Location-based services are computer applications that use location data to control features or the information displayed to the user. They have several applications in health, entertainment, mobile commerce, and transport. In road transport, for instance, location-based services can be used to provide point of interest information (using data held in a navigation database – such as the closest fuel station or restaurant. Location-based services can also be used to display congestion or weather information according to the location of the user (See Servicios Basados en la Localización).

In co-operative systems, vehicles share data with each other and with the road infrastructure using vehicle to vehicle (V2V) and vehicle to infrastructure (V2I) communications. Vehicles that are connected in this way can make use of real-time information on moving objects (such as other vehicles nearby), and on stationary objects that might be transitory (traffic cones, parked vehicles and warning signs). This highly detailed, constantly changing information is held in a data store known as a Local Dynamic Map (LDM). The LDM supports various ITS applications by maintaining information on objects that influence, or are part of, the traffic. Data can be received from a range of different sources such as vehicles, infrastructure units, traffic centres and on-board sensors. The LDM offers mechanisms to grant safe and secure access to this data by means of V2V and V2I communications.

The data structure for the LDM is made of four layers:

Location referencing and object positioning for the upper layers of the LDM is complex and requires adequate location referencing methods. Since not all ITS applications need location referenced information, the use of this data is not mandatory.

These technologies allow the location of vehicles to be ascertained in real-time as they travel across the network. AVL has many useful applications for vehicle fleet management, such as improving emergency management services by helping to locate and dispatch emergency vehicles. AVL can be used for probe vehicle detection and on buses to locate vehicles in real-time and determine their expected arrival time at bus stops.

A number of technologies are available for AVL systems including dead reckoning, ground-based radio, signpost and odometer, and Global Positioning Systems. GPS is currently the most commonly used technology.

Another system for tracking and locating vehicles uses fixed point transponders which can read and communicate with other equipment – for example, toll tags on-board vehicles. These systems can determine when a vehicle passes by a certain point, and provide useful information on travel times and speeds.

A third method for locating vehicles is through mobile phone triangulation. The location of a mobile phone user is identified by measuring the distance to several cell phone towers within whose range the user is located. Using this technology, the location of the vehicle can be identified within an accuracy of about 120 meters. In rural areas, where few cell towers are located, the tower can measure the angle of transmission, which – along with the distance – can be used to locate the phone user even though the user might only be within the range of single cell phone tower. The estimated location in this case is not very accurate (within about 1.6 km).