Porto, Portugal – Traffic operations centre

Ground transport is essential to every country’s economic and social well-being. Many existing road networks have reached the limits of their capacity; so to ensure continued or improved efficiency, effectiveness and safety, better use of the existing infrastructure is essential.

Traditionally, road authorities and other organisations responsible for roads and highways, such as toll road operators, have focused primarily on building and maintaining the infrastructure: roads, highways, bridges and related facilities. Over the years, as traffic volumes have increased, this focus has shifted to place greater emphasis on effectively operating and managing the road networks to minimise disturbances and gain maximum usage. This transition is not easy because it involves re-thinking how the organisations carry out their mission and how the agencies themselves are structured.

Operating the network covers all field operations designed to maintain a satisfactory level of service for road users or, in the event of a disturbance, restore conditions as close as possible to the normal situation.

In the past, road authorities and other organisations responsible for roads and highways, such as toll road operators, focused primarily on building and maintaining the infrastructure: the roads, highways, bridges and related facilities. Over the years, as traffic volumes have increased, this focus has shifted to place greater emphasis on operating and managing the road networks to minimise disturbances and maximise usage. This transition has not been easy because it involves re-thinking how organisations carry out their mission and how agencies are structured.

Road Network Operations (RNO) include all services focused on maintaining the safe and efficient use of highway infrastructure, and associated Intelligent Transport Systems (ITS). Dedicated road network management services have evolved that are designed to keep the road network available for safe use by road-users. Five groups of services can be identified:

1. Traffic management services that are designed to make best use of the available roadway and highway capacity day-by-day in real time – for very heavily trafficked routes and road networks this can be a 24 hours a day, 7 days a week activity.

Traffic management services principally involve responding to “events” as they occur, contingency planning in anticipation of those events, and planning the operational capability to respond appropriately. The events themselves may be:

2. Network control services that seek to control and influence road users over a wide area in order to spread the traffic load and optimise demand on the road network. Examples are balancing demand between alternative routes and integrating network management between different authorities. (See Urban Networks and Regional Networks)

3. Information services that have the capability to:

4. Planning and reporting services that enable response planning for both planned and unplanned events, reports on operational and business services and performance monitoring of the highway network (See Planning and Reporting).

5. Support services that indirectly enable and allow other operational functions to be delivered: for example human resource and shift planning for mobile patrols and traffic control centre operatives, business plans, service development and telecommunications networks across the various functions (See TCC Administration).

Adopting a customer focus for Road Network Operations has many implications. First is the need to keep roads and highways open and available for safe passage wherever and whenever possible: 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. Network Operations are designed to achieve just that.

For road authorities and other organisations closely involved a customer focus means working across administrative boundaries to achieve transport operations that are coordinated and integrated. The operational reach of any single road authority or operating organisation is no longer self-contained. Operational objectives have to be defined according to the road users’ needs. This means that to a great extent Road Network Operations must be integrated:

The Institutional issues in network operations are significant because of the number of stakeholders involved. Network operations can:

How Road Network Operations (RNO) are organised varies significantly from place to place. The missions, responsibilities and needs of the organisations involved can be quite different. In many countries, the national ministries/departments of transportation have primary responsibility for strategic roads; whereas provincial and even local agencies are responsible for other types of roadways. In many countries there is a significant role for the private sector.

Close coordination is critical between all the relevant agencies, operating partners, task forces dedicated to incident management or security, external news media and information service providers. This sometimes takes the form of a regional transport operations coalition with parties that include the road network operators, law enforcement, emergency vehicle operators, public transport operators, port operators and public and private providers of information – such as weather and various commercial activities. The degree of coordination involved differs depending on local priorities the need for coordination and the characteristics of the road network. (See Inter-Agency Working)

In order to ensure smooth implementation, roles and responsibilities must be clearly defined, including identification of technological requirements and who takes responsibility in emergencies and other critical situations.

The division of roles between different organisations can be set out within a legal framework where public institutions are involved, or in a more contractual arrangement such as PPP (Public Private Partnerships) when the private sector is involved. Close coordination between all stakeholders will ensure seamless operations that will benefit the road user. (See Public Private Partnerships)

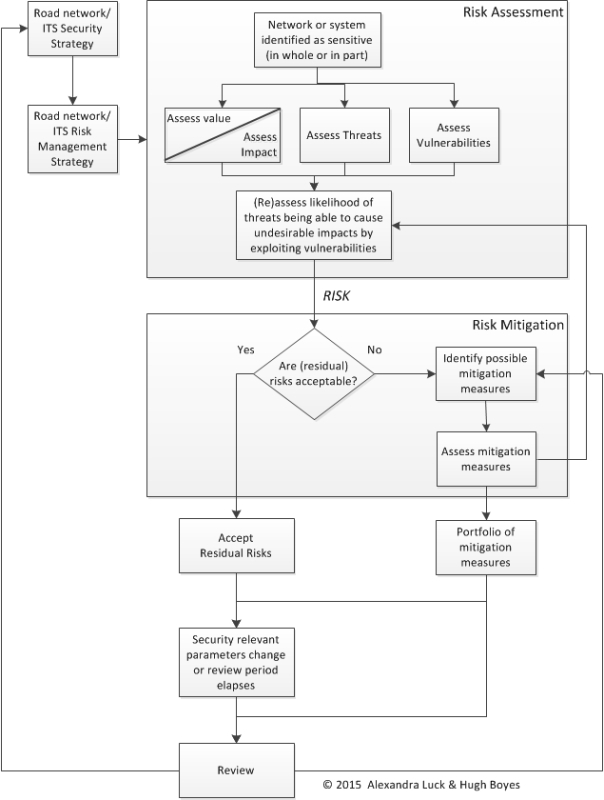

Sharing of information and responsibilities between and across organisational boundaries can be a challenge. Nevertheless, significant progress has been made in gaining acceptance and support for ITS applications that enable effective information sharing and collaboration - while addressing concerns associated with differing priorities and requirements among the stakeholders.

A “region” may be anything from a greater metropolitan area, such as Greater London, to a geographic sector of a nation or state, and can be extended to a cross-border international operating organisation, such as the Niagara International Transportation Technology Coalition (NITTEC) covering parts of western New York State in the USA and portions of Ontario, Canada.

At the local (city, county or toll road) levels, operations have a prominent role, because of the need to manage conflicting flows of traffic and share capacity evenly – or equitably – at junctions and for junction to junction coordination.

A regional operating partnership is a means of fostering relationships and building cooperation among entities that may otherwise have few, if any, opportunities to interact. These collaborations are a means of sharing information, experience, successes, problems and mutual needs with stakeholders in the broader region. A key output of such collaboration is often the development of a regional ITS architecture. (See ITS Architecture)

In the UK legislation requires local road and highway authorities to nominate “traffic managers” and coordinate traffic management with neighbouring authorities. The national operator of the strategic road network has also entered into local operating agreements with operators of local roads.

The ITS infrastructure for regional operations is made up of a number of different features. For the systems to work properly, ITS services need all the basic components in place and these must be fully and reliably operational. For example a lack of basic infrastructure affecting any part of the information supply chain will lead to poor-quality information services and ineffective and inefficient network management. (See Data and Information)

Designers and installers of ITS for road network operations should consider the probability of roadside equipment being struck by passing vehicles and locate the equipment accordingly. Structures and poles holding ITS devices on high-speed highways should be shielded by collision-tested barriers, both to protect the equipment and to make any crash less severe. Similarly, potential threats of weather should be taken into account.

The technical requirements for regional ITS operations include:

Working across jurisdictions is essential: the technologies, procedures, planning and preparations to support management of recurring and non-recurring congestion have to be integrated. Experience clearly illustrates that providing the means for representatives of partner entities and task forces to meet and discuss common concerns and needs helps improve effective coordination and the building of relationships that significantly enhance common policies and practices, when, for example, incidents or emergencies occur.

Traffic Control Centres (TCCs) are directly or indirectly involved in most RNO operating strategies to some extent. For example TCC managers and operators can use Advanced Travel Information Systems (ATIS) to help mitigate the impact of non-recurring congestion in various ways. The objective is to deliver an as near as possible congestion-free network through the use of direct control measures and maximising the dissemination of traveller information using all available channels, particularly VMS, telephone information services (511 in USA), Highway Advisory Radio, internet web sites and social media. (See Traveller Services)

Traffic Control Centres (TCCs) are known by different names in different regions of the world. Even in Europe, where the term TCC is common, some cities also have multi-modal Travel Information Centres (TICs). Some of the core activities for a TCC are to issue traffic information, which makes the term confusing.

In North America and Australia the term Transportation (or Traffic) Management Centre (TMC) is commonly used. Some USA centres and most in South America are called Traffic Operations Centres (TOCs). In the USA, “traffic control centre” is often used for (usually local) centralised traffic signal system control centres.

To avoid confusion, this website uses TCC to cover all such centres, unless otherwise stated.

TCC managers and operators can use ITS components to manage traffic and respond to incidents and emergencies. Typically ITS functionally in TCCs includes:

The primary focus of many TCCs tends to be on supporting traffic management activities on major roadways, including incident response. While this may remain their primary function, a growing number of centres are finding ways to interact, share information and collaborate with partners in the overall management of the road system. Snowplough and ice mitigation operations are examples.

One of the key elements in planning for Road Network Operations is to ensure the successful design, implementation, operation and maintenance of the Traffic Control Centres (TCCs). This planning should be based on completed ITS studies and initiatives for the region such as a regional ITS architecture, strategic deployment plan, a “Concept of Operations” for the TCC – and operations and management plans. (See How to Create an Architecture)

The Concept of Operations for a TCC is a high-level description of system capabilities that are based on a vision, goals, identified needs and high-level requirements that are mutually agreed between the leading stakeholders. This forms the basis for defining the detailed requirements and for producing a high-level design. The Concept of Operations will also identify other major stakeholders, planned network coverage and operating hours and required resources (for example, hardware, software, facilities and personnel).

Guidance on how to develop the Concept of Operations for a TCC has been prepared by the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) in the USA (see below). A Concept of Operations document will form a solid basis for establishing TCC operations and maintenance procedures, acquiring and utilising resources and interfacing with TCC stakeholders. The stakeholders include other public entities, private-sector companies, the general public and the media.

A video depicting various scenarios in a futuristic TCC, the TMC of the Future, can be accessed in ITS America's Knowledge Centre under "Featured Videos" at http://itsa.org/knowledgecenter/knowledge-center-20.

The video runs for about 45 minutes. It was produced by the Intelligent Transportation Society of America (ITSA) for the 2008 ITS World Congress in New York City. Using actors, various traffic and incident scenarios were “performed” to live audiences. The TCC featured the more advanced features of a modern TCC and stressed the interagency activities in response to the “incidents” occurring. This video captures one performance.

It features the future use of what in 2008 was called "Vehicle-Infrastructure Integration (VII)" – but is now referred to as "connected vehicles" in the USA and “Cooperative Vehicle Highway Systems (CVHS)” elsewhere. The CVHS programme globally is still largely in the Research and Development (R&D) stage, so its use in the TCC is largely futuristic, although one of the key elements is the use of Floating Vehicle Data for traffic flow characteristics, which is becoming commonplace (See Probe Vehicle Monitoring and Probe Data).

The video shows this TCC also operates traffic signals on the arterial network and Integrated Corridor Management - which are increasingly being implemented across the world. It also addresses integration with other transport modes and services, such as public transport and parking and congestion pricing.

A Traffic Control Centre’s functions vary according to which agency operates it. The functional “separations” between motorway and urban network control are not rigid distinctions; and, ideally, the two would merge to enable fully integrated Management and Operations. Some countries, states or regions have moved in this direction, but it can involve considerable effort and expense.

The organisational and operational responsibilities of TCCs for different types of network varies:

There are no clear technology differences between these three groups and they often overlap in function, but the institutional differences are more distinct. Advanced ITS applications provide the means for regional and local TCCs to work together, coordinate activities and share information when the need arises. (See Integrated Operations)

In many countries a growing number of local agencies have, or plan to develop, local fully functional TCCs, which are organised and operated to support the responsibilities of local agencies. On a daily basis this allows each TCC to effectively carry out its core mission.

The various services provided by a TCC can be grouped according to high-level functions, such as those shown in the diagram and described below:

![Figure 1: Example of Traffic Control Centre Activities and Services (Source: UK Highways Agency) [Copy permission needed] Example of Traffic Control Centre Activities and Services (Source: Highways England UK)](/sites/rno/files/public/wysiwyg/import/network-operations/1430317452html_html_a9c9bf5.png)

Example of Traffic Control Centre Activities and Services (Source: Highways England UK)

The TCC needs decision support information on the network including a database of road network characteristics, information about incidents and other events (roadworks, accidents), traffic flow and journey times, and weather conditions.

This requires the TCC to adopt systems for:

1. the network description and location referencing (See Basic Info-structure)

2. obtaining information about:

3. continuous monitoring of:

(See Data and Information, Traffic & Status Monitoring and Weather Monitoring)

The TCC needs to develop traffic management response plans that support its control strategies and the choice of information to be provided during incidents that affect traffic on the network. When incidents occur the TCC will implement these plans and analyse and update those plans on the basis of experience.

This requires:

(See Integrated Strategies)

These are the means by which a TCC provides information to media organisations, road users and the travelling public . They may include providing VMS at key locations on the road network, providing an internet site for public information – and use of social media and an interactive telephone service.

Specifically the TCC core services will be:

(See Travel Information Systems and Traveller Services)

These are activities that enable the TCC to provide information and take action that will improve the ability of other organisations (operating partners) to perform their duties in managing the traffic and operations on their networks. The TCC needs to establish links with the traffic controllers for site that generate traffic or are major destinations. Examples might be a ferry port or airport, shipping container terminal, mineral extraction sites, major sports or entertainment centres, retail parks and shopping malls

They include:

(See Planning and Reporting, Public Transport Operations & Fleet Management and Operations & Fleet Management)

Management services relate to the day-to-day operation of the Traffic Control Centre and any additional operations that are required, specifically:

For a TCC that covers toll road operations the ITS traffic systems and the electronic tolling systems are usually completely separate. They are not permitted to integrate, at least electronically, to protect the integrity of toll revenues. Toll-road TCCs generally manage incidents in the same way as their non-tolling counterparts. The fact that they operate facilities whose users are paying in real-time increases the pressure to clear incidents quickly. In some locations, such as Santiago, Chile, various toll roads use the same transponders to identify all vehicles passing through the toll gantries.

(See Toll Collection)

Urban Traffic Control Centres (TCCs) have operated traffic signal systems for years using a wide range of software packages. Their main purpose is to keep traffic moving in the urban network of arterial roads. As more ITS devices are being deployed in the arterial networks, the use of ITS for Arterial Traffic Management Systems (ATMS) is becoming commonplace. European practice is to refer to Urban Traffic Control (UTC), or Urban Traffic Management and Control (UTMC).

A summary of operations for a TCC that controls an urban arterial road network is given in the tables below. (See also TCC Functions)

|

Operational Function |

Operational Method |

Resources Used |

Desired Result |

| Surveillance |

Visual monitoring |

CCTV, video wall, work-stations, video “tours” |

Maximum visual coverage of network |

|

Sensor monitoring |

Electronic detectors |

Maximum sensor coverage of network, capture traffic characteristics |

|

|

Vehicle probes |

Mobile safety patrols, crowd sourcing, floating vehicles |

Detect and verify incidents in timely fashion |

|

| Traffic control/ influence |

Signal operation |

Traffic signal controllers |

Regulate traffic flow through intersections, along corridors and in networks |

|

Traveller information |

Inform public and logistics managers of conditions for self-decisions |

|

Operational Function |

Operational Method |

Resources Used |

Desired Result |

|

Traffic control/ influence |

Signal operation |

Traffic signal controllers and traffic control software |

Regulate traffic flow particularly along corridors and through networks |

|

Contra-flow or other special lane use |

Lane signals, VMS |

Increase roadway capacity |

|

Operational Function |

Operational Method |

Resources Used |

Desired Result |

|

Surveillance |

Sensor monitoring |

RWMS (although rare on arteries) |

Detect adverse weather |

|

Visual monitoring |

CCTV, video wall, workstations, video “tours” |

Detect and verify adverse weather |

|

Operational Function |

Operational Method |

Resources Used |

Desired Result |

|

Surveillance |

Visual monitoring |

CCTV, video wall, workstations, video “tours” |

Detect and verify incident, dispatch response, notify other responders |

|

Incident notification |

Police, Emergency Control Centres |

Initiate response |

|

|

Vehicle probes |

Safety service patrol (if used) |

Detect incidents, SSP respond and assist |

|

|

Signal operation |

Adaptive signal controllers |

Regulate traffic flow around incident |

Improve throughput |

|

Traveller information |

Encourage diversions and journey time changes |

|

Operational Function |

Operational Method |

Resources Used |

Desired Result |

|

Traffic control/ influence |

Traveller information |

Safe, free flow past maintenance and other road work or diversion of route |

|

Resource |

Technology |

Further information |

|

511 (USA) |

Telephone travel information system |

|

|

Closed-circuit Television |

||

|

eCall |

Automated vehicle collision reporting system |

|

|

Electronic detectors |

Vehicle and pedestrian sensors |

|

|

Highway Advisory Radio |

||

|

Lane signals |

Overhead VMS showing lane availability |

|

|

Media feed |

Automatic feed of information to websites, radio and TV stations |

|

|

PDMS |

Portable Dynamic Message Sign |

|

|

Queue detectors |

Electronic sensors to detect queues / queue length |

|

|

Ramp signals |

Traffic signals to control traffic volumes entering a motorway / freeway |

|

|

RWMS |

Road Weather Management Systems |

|

|

Social media |

Facebook, Twitter, etc |

|

|

Speed advisory VMS |

Advisory Variable Message Signs |

|

|

Speed limit VMS |

Mandatory Variable Message Signs |

|

|

Video “tours” |

Successive display of CCTV images from different cameras |

|

|

Video wall |

Wall-mounted screens to display CCTV images |

|

|

Variable Message Signs |

The tables below summarise the typical activities that a Traffic Control Centre will perform for different types of traffic conditions on motorways, freeways, expressways and other regional arterial roads. The desired results (operational outcomes) are indicative of the specific situations. (See also TCC Functions)

Not all of the resources mentioned below will be present in every control centre. Field network telecommunications, device controller infrastructure and control room systems and software, are common to all and are not mentioned in the tables.

|

Operational Function |

Operational Method |

Resources Used |

Desired Result |

|

Traffic Monitoring and Surveillance |

Visual monitoring |

CCTV, video wall, workstations, video “tours” |

Maximum visual coverage of network |

|

Sensor monitoring |

Electronic vehicle detectors |

Maximum sensor coverage of network to capture traffic characteristics |

|

|

Vehicle probes |

Mobile safety patrols, crowd sourcing, floating vehicles |

Detect and verify incidents in timely fashion |

|

|

Traffic control/ influence |

Travel & Traffic information |

Inform public and logistics managers of conditions for self-decisions |

|

Operational Function |

Operational Method |

Resources Used |

Desired Result |

|

Traffic control/ influence |

Ramp metering |

Ramp signals, queue detectors |

Smooth merging, effect minor diversion |

|

Contra-flow, High Occupancy Toll, shoulder running or other special lane use |

Lane signals, VMS, PDMS |

Increase roadway capacity |

|

|

Variable speed limits |

Speed limit VMS |

Stabilise flow |

|

Operational Function |

Operational Method |

Resources Used |

Desired Result |

|

Surveillance |

Sensor monitoring |

Road Weather Management Systems |

Detect adverse weather |

|

Visual monitoring |

CCTV, video wall, workstations, video “tours” |

Detect and verify adverse weather |

|

Operational Function |

Operational Method |

Resources Used |

Desired Result |

|

Surveillance |

Road-user reports |

Cell-phones, emergency telephones, social media |

Operators alert to possible incident |

|

Visual monitoring |

CCTV, video wall, workstations, video “tours” |

Detect and verify incident, dispatch response, notify other responders |

|

|

Sensor monitoring |

Electronic detectors |

Incident detection algorithms: automatic alert for potential incident |

|

|

Incident notification |

Police, Emergency Control Centres |

Initiate response from rescue and ambulance services, vehicle recovery, emergency repair operators |

|

|

Patrol vehicles |

Safety service patrol, road watchers |

Detect incidents, Mobile patrols respond and assist |

|

|

Traffic control/ influence |

Travel & Traffic information |

VMS and signals, PDMS, HAR, 511, website, media feed, social media |

Encourage diversions and journey time changes |

|

Ramp metering |

Ramp signals, queue detectors |

Smooth merging, effect increased diversion |

|

|

Speed advisory |

Speed advisory VMS |

Calming of speeds and reduced lane changing |

|

|

Variable speed limits |

Speed limit VMS |

Reduce limit to safe speed |

|

|

Lane use control |

Lane signals |

Open/close lanes as appropriate |

|

|

Maintenance of traffic |

VMS, PDMS |

Safe, free flow past maintenance and other road work |

|

|

Queue warning |

VMS, PDMS |

Reduced secondary incidents; Safe, free flow past maintenance, other road works and incidents |

|

Operational Function |

Operational Method |

Resources Used |

Desired Result |

|

Traffic control/ influence |

Traveller information |

VMS, PDMS, HAR, eCall (511), website, media feed, social media |

Safe, free flow past maintenance and other road work or diversion of route |

|

Resource |

Technology |

Further information |

|

511[USA] |

Telephone travel information system |

|

|

Closed-circuit Television |

||

|

eCall |

Automated vehicle collision reporting system (Europe) |

|

|

Electronic detectors |

Vehicle and pedestrian sensors |

|

|

Highway Advisory Radio |

||

|

Lane signals |

Overhead VMS showing lane availability |

|

|

Media feed |

Automatic feed of information to websites, radio and TV stations & via social media |

|

|

PDMS |

Portable Dynamic Message Sign |

|

|

Queue detectors |

Electronic sensors to detect queues / queue length |

|

|

Ramp signals |

Traffic signals to control traffic volumes entering a motorway / freeway |

|

|

RWMS |

Road Weather Management Systems |

|

|

Social media |

Facebook, Twitter, etc |

|

|

Speed advisory VMS |

Advisory Variable Message Signs |

|

|

Speed limit VMS |

Mandatory Variable Message Signs |

|

|

Video “tours” |

Successive display of CCTV images from different cameras |

|

|

Video wall |

Wall-mounted screens to display CCTV images |

|

|

Variable Message Signs |

Successful Traffic Control Centre operations require effective administration. A basic requirement is easily accessible and well-organised reference documentation for control centre staff. A set of policies, plans, guides and instructions is needed to guide TCC managers and operators in their duties and collaboration with others (operating partners and other stakeholders).

A minimum set of documents, available in hard copy and/or on-line electronically, will be:

The establishment of a business plan is recommended to provide a roadmap for agencies to establish the TCC goals and objectives and to achieve them. A properly implemented TCC business plan will provide justification for sustained operations by means of on-going performance measurement and reporting of outcomes. The business plan also helps to identify the present and desired future state of the TCC’s operational effectiveness and key gaps that need to be addressed. The plan will include:

TCCs require significant and committed funding for their deployment, operation and maintenance. A lack of continuing funding will affect and limit the desired results. Adequate staffing and operations planning are also necessary. The majority of transport agencies run TCCs with public-sector staff but some outsource the TCC operations to private-sector companies – sometimes because it has been a challenge to staff and train personnel to effectively operate the TCC.

Key to successful road network operations is the inter-agency, multidisciplinary integration of the TCC with the operational activities of other organisations that have a part to play or who manage adjacent highway networks. This is referred to by some as the “4-Cs": Communication, Cooperation, Coordination, Consensus.

Managing routine traffic, traffic incidents and even transport emergencies is greatly enhanced by organisations collectively applying the 4-Cs. This is best done when centres like the TCC, Emergency Control Centre (ECC) and/or Emergency Operations Centre (EOC) are co-located – or at least have close two-way communication for data and information exchange and sharing of CCTV camera images. For example, information seen on camera can be actively provided to those responding to a traffic incident (police, fire, other emergency services, towing companies and maintenance) so responders can request the resources they need.

The vast majority of ITS technology is deployed in urban areas and alongside motorways, although some ITS devices are deployed in remote rural areas. Given the distances involved, this poses an economic challenge to the responsible organisation. Wireless communications overcome some of the challenges – but full coverage for surveillance and traveller information is still difficult. The increasing use of Floating (or Probe) Vehicle Data (FVD) provides TCCs with the ability to access data that can indicate rural incidents and trigger both response and information dissemination to travellers and responders. (See Probe Vehicle Monitoring)

ITS asset management includes not just hardware, but also software and key personnel, in order to support the long-term goals of the organisation and maintain its ITS capability. General guidelines include:

For information on Traffic Control Centre staffing See http://ops.fhwa.dot.gov/freewaymgmt/publications/frwy_mgmt_handbook/chapter14_04.htm

It is essential that managers provide comprehensive training in every aspect of traffic management and related topics to the staff who have a role in TCC operations.

Training comes in many forms, among them:

Field exercises are generally more appropriate for those who respond to incidents on the road or highway. In-house exercises can be designed for TCC operators – the challenge is the ability to simulate actual operations and procedures including the use of equipment and devices. Some centres have demonstration equipment that can be used for this purpose.

One-on-one training and small group on-job training is most likely to be recalled by those who experience it but it takes time to encounter a wide variety of situations. The more interactive the training can be, the more effective it will be in producing lasting success.

A useful report on “Impacts of Technology Enhancements on Transport Management Centre Operations,” produced by the Transport Management Centre Pooled Fund Study (TMC PFS) in the USA, provides guidance to TMC/TCC managers on how to better position themselves operationally in anticipation of future technology changes and advancements. (See http://www.ops.fhwa.dot.gov/publications/fhwahop13008/index.htm)

Effective Road Network Operations (RNO) require that the network monitoring and traffic control systems are fully functional. This is accomplished most effectively by monitoring the system components. There are two aspects to this:

Traffic Control Centre (TCC) software will monitor the incoming data, images and other media from the field devices that are used for routine traffic management and incident detection, verification, notification and dispatch.

Within the TCC, the software automatically monitors the status of its key processors, servers, video displays, communications and all the other assorted equipment – and the software itself – to ensure a high level of operational efficiency. Equally important, these form the core of data and information used for performance management. (See Planning Procedures)

Monitoring system performance is essential in evaluating its success in achieving its objectives. Typically, the TCC software will have modules that automatically monitor the various components to detect and report failures or other anomalies that need to be brought to the operators’ attention. Depending on the device type, in legacy systems this is generally achieved through: periodic polling of the devices to sense expected responses, monitoring of data streams for continuity – and other diagnostic techniques.

As device sophistication improves the trend is to incorporate more self-diagnostics, pushing data on equipment status and performance to the central system. The results of the monitoring are used for instant failure reporting, as well as providing system performance measures over time.

From a traffic operations perspective, system monitoring and automatic fault reporting is essential. It enables the TCC operators and managers, along with the maintenance team, to keep the system healthy to perform its tasks in managing traffic and providing situational awareness to the travelling public. System monitoring helps to ensure that managers can be confident that the investment in ITS is being nurtured and protected through proper operation, or that problems are identified and can be addressed promptly.

In the USA, Florida’s Turnpike Enterprise operates a unique tolling and revenue monitoring system. The SunWatch Centre monitors all equipment in the system, alerts operators to malfunctions and failures, and takes action to mitigate the problem.

Given the nature of its operations, the SunWatch Centre is not widely advertised, but some information is available from the International Bridge, Tunnel and Turnpike Association’s website at http://ibtta.org/awards/sunwatch-operations-center

ITS asset management includes not just hardware, but also software and key personnel, in order to support the long-term goals of the organisation and maintain its ITS capability.

Maintenance activities on ITS devices and traffic signal systems can impact on Road Network Operations. When ITS is first deployed, the equipment is new and does not require extensive maintenance resources. As systems expand and age, there is a continuing need for – and complexity of – maintenance operations.Two aspects of maintenance have a direct impact on operations:

There are two types of routine maintenance: preventive and responsive.

Preventive Maintenance is generally regularly scheduled maintenance designed to pre-empt device failure that would render the device unserviceable. Preventive maintenance will extend the active life of devices and subsystems. It can use past experience to anticipate when devices should receive attention. Automated maintenance management systems base the scheduling on a number of factors that are analysed by the software to produce a schedule.

Preventive maintenance can be as simple as cleaning cabinets and cable runs/conduits, securing wiring and printed circuit board connections, to scheduled pre-emptive repair. Alternatively it can entail replacement of components or entire devices.

Responsive maintenance (or reactive maintenance) concerns the repair or replacement of a component or system following failure or damage caused by a collision or other incident. Failed ITS equipment and non-functioning network monitoring devices will not provide the images, data or information needed to help maintain stable traffic flow.

When failures occur the devices cannot perform their functions, which will often be detrimental to RNO. Responsive maintenance should be the highest priority, since restoring equipment function is the key objective. It is advisable for TCC operators to prioritise conflicting maintenance needs, rather than leaving maintenance staff to determine this themselves.

The key to successful maintenance is to have a complete, manageable inventory of all devices. Automated support software can be an ideal way to maintain the inventory – and can also assist in preventive and responsive maintenance operations. (See Data Management and Archiving)

Florida Department of Transportation provides an example of a combined ITS Maintenance Management Systems (MMS) and Fibre Management Systems (FMS), known as the ITS Facility Management System (ITSFM). (See http://www.dot.state.fl.us/trafficoperations/ITS/Projects_Telecom/ITSFM/ITSFM.shtm)

Factors that lead to the adoption of an automated maintenance system include:

Most Traffic Control Centres (TCCs) have “up-time” targets for system availability that challenge the maintenance team to keep devices operational at least a certain percentage of time, for example, 98% or 99% availability. Only automated systems can both organise the maintenance activities and keep track of them. An ITS maintenance management system and a communications management system are part of the ITS operation, just like the TCC software. If the RNO organisation operates its own comprehensive telecommunications networks, this will justify a telecommunications “network manager”, which is common place in the telecommunications sector.

Systems maintenance can be performed either by in-house staff or outsourced to others—usually original equipment suppliers but also third party maintenance companies. In some regions the trend is towards outsourcing systems maintenance to private contractors. The substantial differences in the nature of ITS and roadway maintenance, generally leads to ITS maintenance being outsourced to a specialised electrical contractor.

Some large consulting firms are increasingly expanding their involvement in this business, sometimes called asset management.

The purpose here is to maintain ITS equipment or restore it to a condition that can effectively handle the assigned functions, at the lowest possible cost. To achieve this objective, the operator must:

Organisational arrangements will depend on the size of the maintenance operation, the volume, nature and location of equipment, and the resources and skills available. Organisations will need to determine the scope of maintenance activities to be undertaken internally by the operating organisation and those that will be sub-contracted.

Effective maintenance is based primarily on detailed wording of supply contracts, follow-up and effective handover. This is to ensure a precise definition of the work to be performed, conditions of delivery, contract deadlines for restoring service and penalties for non-compliance. It also relies on:

Motorway Maintenance Management Systems (MMMS) generally operate on limited-access roadways, which carry high volumes of traffic at relatively high speeds. Disruption to traffic adversely impacts traffic operations. Fortunately, many ITS devices are located off the roadway, but within the s of way, so maintenance activities can be conducted without directly interfering with traffic. Even in these cases temporary traffic control devices may be required for the protection of the maintenance crew. Efficiency of maintenance operations is essential.

The mere presence of maintenance vehicles causes driver distraction (“rubbernecking”), in the same way as roadside incidents. This is a particular concern in restricted situations, for example part of a tunnel or long bridge. Working on, or adjacent to, live carriageways is hazardous and some simple precautions are needed – for example, high visibility clothing, hazard lights and deployment of temporary traffic management to close lanes.

There is greater traffic disruption when the maintenance crew must work over an active lane or median shoulder, such as on the exterior of a VMS. When this happens, the crew is generally required to close the lane(s) over which they work and deploy temporary measures to maintain traffic flow. This work should, whenever possible, be done during off peak times to minimise the adverse effect on traffic. The work is often contracted out to specialist firms to provide temporary traffic management. The TCC will need to be vigilant in ensuring that measures to maintain traffic flow are in place and are operating effectively at all times.

These considerations apply equally to maintenance of routine traffic control and information devices, such as fixed signage – so general maintenance should follow the same practices as the ITS maintenance agency. The TCC should be notified whenever there are activities on the motorway, particularly if lanes are to be closed. Some countries use Lane Closure Management Systems to schedule and manage closure requests and contractor roadwork.

Particularly dangerous work sites – for example on one of the traffic lanes – should be protected by a crash barrier (crash-attenuator or crash cushion) such as a vehicle or trailer positioned upstream of the lane closure. In Santiago, Chile, one of the urban toll road operators requires all providers of maintenance to equip work crews with such equipment.

The primary difference between motorway and urban arterial road networks is that in the urban situation considerably more maintenance has to be done on, or immediately above, the roadway itself. Traffic signal heads, supporting span arms, signs, wires and overhead vehicle detectors are all located over the roadway. Devices off the roadway, such as signal cabinets and other ITS equipment, will also generally be located in less open spaces. If a hard shoulder is not available it is likely they must be accessed from a traffic lane. Lane closures are far more likely on urban arterials roads and city streets.

Many high-capacity urban arterial roads experience traffic speeds that are not significantly slower than a motorway. Other roads have lower traffic volumes, particularly off peak, and traffic speeds may be lower too. Temporary traffic management is important and without it, conditions may be unsafe. The number of movements possible (such as driveways and turning movements) also greatly increase hazards. The paramount objective must be the safety of the maintenance crew.

Traditional planning processes in roads and highways authorities have focused on capital improvements to roadways. In many countries there were few mechanisms to effectively support ways of improving road network operations or to support thinking beyond the physical construction of facilities and infrastructure. This is changing to allow consideration of how road and highway facilities can operate most effectively.

Planning for operations is inevitably part of the long-term planning effort, but the planning process needs to be more than simply planning for, and funding of, the installation of additional infrastructure. Specifically, planning for operations should ensure a long-term, adequate and reliable source of funds for day-to-day traffic operations and maintenance of the ITS infrastructure.

Planning for Road Network Operations (RNO) now normally includes three important aspects:

Linking together planning and operations will encourage an improvement in transport decision-making and the overall effectiveness of transport systems. Coordination between the planners and operating units helps ensure that regional transport investment decisions take account of the available operational strategies that can support regional goals and objectives.

In summary, the success of RNO is closely related to the strategic role and objectives of the transport agencies responsible for RNO – such as:

These “high-level” concepts should guide agencies in their formulation of policy and operational practices. (See Traffic Management and Demand Management)

Planning for Road Network Operations involves consideration of the organisational requirements for the operational activities including preventive actions. Practical constraints (such as inter-agency demarcations) and on-going local factors must be defined together with the supporting information systems and decision-making or control systems that are needed. The success of a plan depends on the distribution of activities between partners and on their full knowledge and understanding of their assigned tasks.

Generally, design procedures require the following:

The lead organisation for traffic management on the network will need a reliable database for preparing, organising, implementing, managing and assessing operations more effectively. This will enable the organisation to become a valuable resource for addressing ad hoc issues concerning the network, the need for studies and for providing statistical material for publications. (See Data Management and Archiving)

Data includes:

This data will be supplemented with:

The tools needed to establish the database are:

The network management database is not static: there will be a continual, on-going requirement for up-dates.

Maintenance of the data files is a meticulous, time-consuming process that demands specific training to achieve the results required. Theoretical knowledge of the network and its environment must be supplemented with hands-on experience and local knowledge. For example, to determine whether a planned detour is realistic, it is necessary to know as accurately as possible the level of traffic on each road segment. Lessons learnt from the analysis and response of actual situations must be factored into establishing response procedures for future events.

The purpose of an events database is to forecast periods when the probability of traffic disruption is high. The task consists of studying the calendar (dates of public holidays, school holidays and major planned sporting, cultural and entertainment events) and comparing it with previous years, comparable past situations and/or weather forecasts.

Implementation involves specific stages:

The task requires painstaking attention to detail in collecting and analysing data, particularly keeping logs. It is vital work and helps improve the management of the road network – thereby decreasing the number of unplanned incident and emergency response situations.

The purpose of a procedures manual is to define the operating actions of all roadway partners and guide their implementation. A procedure manual consists of listing all tasks to be performed and all resources required to carry out the task specified for each event or incident scenario. Procedure manuals can be produced for roadworks, mobile traffic patrols, traffic monitoring and traffic management plans. The production of procedure manuals is a good subject for initiating and fostering cooperation with partners.

The events to be handled and their consequences will sometimes differ slightly from the scenarios studied. Although procedure manuals need to be detailed, they can and should leave room for some initiative by those at whom they are aimed.

Since procedures manuals are tools common to many partners, it is important to ensure that the reference framework and vocabulary are understood by all. The design of manuals that link to various plans – must be consistent and support cross-referencing. They must be periodically updated and the updates to all documents must be distributed. The provision of procedure manuals on-line may be the best way of keeping them current and available.

There is a twofold objective in tracking the performance of the operating measures:

Monitoring methods must be developed to quantify the impact of the measures implemented and detect dysfunctions or serious variance from anticipated results.

This approach relies on information gathering that must be a systematic and a planned part of routine documenting procedure (logs, fact sheets and other reports).

A small number of basic performance indicators must be defined case-by-case and changes tracked over time. To define these indicators without overlooking key points, the following factors can serve as a guide:

The purpose of updating the operating procedures is to plan for, and justify, the resources appropriate to the context. Resources can include hardware, software and documents as well as personnel organisation and training. The context will cover the traffic situation, incident response infrastructure, organisation of other services, user needs and available technologies.

Updating procedures and operating methods extend to physical assets as well as documentation and service organisation. It specifically requires:

This work requires effort that is rarely spontaneous – and ultimately may highlight needs for specific resources (studies and production of documents). The outcome may be elimination of unnecessary or out-dated working methods. It is also fairly common for objectives and strategies that are initially defined – to be revised in light of experience gained.

A Traffic Management Plan (TMP) provides for the allocation of traffic control and information measures in response to a specific, pre-defined traffic scenario – such as the management of peak holiday traffic or the closure of strategic route because of bad weather, maintenance or a serious road accident. The objective is to anticipate the arrangements for controlling and guiding traffic flows in real-time and for informing road-users about the traffic situation in a consistent and timely way.

The plans, which will differ in detail according to local circumstances, apply in the following cases:

TMPs do not solve all traffic problems but lessen the consequences. They improve coordination and cooperation between partners and facilitate the establishment of mutual agreements on the operational requirements.

A TMP will optimise the use of existing traffic infrastructure capacity in response to a given situation and provide a platform for a cross-regional and cross-border seamless service that provides consistent information for the road user. The situations covered can be unforeseeable (incidents, accidents) or predictable (recurrent or non-recurrent events). The measures are always applied on a temporary basis – although “temporary” may be lengthy, such as a construction or long-term maintenance activity.

TMPs define and formalise:

The purpose of this approach is to limit the effects of events that can lead to serious deterioration of traffic conditions and to enhance road safety. The objective is coordinated action by the various authorities and services that participate in the operation of the roadway.

TMPs can be developed for corridors and networks with the aim of delivering effective traffic control, route guidance and information measures to the road user. An improvement in overall performance is possible by securing effective collaboration and coordination between the organisations directly involved. By strengthening cooperation and mutual understanding a more integrated approach will be achieved to the development, deployment and quality control of traffic management measures. (See TCC Functions, Urban Operations and Highway Operations )

Four geographic levels can be considered for the elaboration of Traffic Management Plans:

Multiple level TMPs, if properly developed, will provide for various traffic situations in a timely and effective manner.

The implementation of TMPs eases roadway disruptions even if the initial event and its consequences are slightly different from the scenarios adopted for the TMP. When a TMP is put into practice the introduction of measures not included in the plan can be initiated by the operator – provided that the new measures are consistent with the spirit of the plan, after agreement with the coordinating authority. Common terminology and an agreed referencing system for key locations are essential for all stakeholders to understand each other clearly. It is essential that everyone has access to the most up-to-date version of the TMP, making version control very important. The wide distribution of TMP documents can lead to different parties working to different versions but this can be avoided if the current versions are held on-line in a virtual library.

TMPs are produced from historic analysis and a consideration of potential operating measures and agreements between all future partners and stakeholders. After a TMP has been activated and the situation returns to normal, feedback from the experience will help improve the effectiveness or performance of future activations.

The objective of systematic feedback – often called “after-action” analysis – is to enhance the effectiveness of an operating plan or action and optimise use of resources. Past situations are used to review organisational factors, event planning procedures and detailed incident response plans.

To secure feedback to the required level the following measures are recommended:

Organising and using feedback is especially important where the operational plan or measure implemented has not previously been applied in a wide-scale exercise or test.

A survey of all planned roadworks will provide important data for the Traffic Control Centre to assess the duration and the time-line of forecast obstructions and develop the least disruptive master plan. This task requires control centre operator awareness and proficient scheduling.

There are some drawbacks and constraints - such as:

The objective will be to schedule roadworks to minimise their impact and reduce disruption to road users, for example by avoiding:

The goal is to minimise the actual or probable disruption to users caused by major construction works by initiating consideration of:

The optimum plan for roadworks operations can be developed by progressively focusing on the best approach for executing the roadworks, incorporating safety concerns and traffic flows, and integrating these considerations and the results into the plan.

This requires knowledge of:

Sometimes several solutions will be available (local detour, alternative routes, alternating open lanes). The choice will be based on total cost, including the cost of work and cost of delays. While work is in progress it is important to check compliance of signalling and operating methods with the content of the operations plan.

A Traffic Incident Management (TIM) team drawn from the leading organisations involved in responding to traffic incidents is useful in many situations. The team can operate as a unit to create the required contingency plans and the related Concepts of Operations (ConOps) – that identify stakeholders and their respective roles and responsibilities in incident management. (See Traffic Management Plans)

An Incident Management Team can be a continuing mechanism for practicing the essential “4-Cs’ of incident management – Communication, Cooperation, Coordination and Consensus – sharing new techniques, training and conducting post-incident assessments. This is done through regular, on-going meetings, perhaps monthly or bi-monthly.

There should be a core group that participates regularly in the continuing activities of the team. Usually this would include:

If there is a TCC in the region, it will be a core TIM member as well. The TCC may take the lead in forming the TIM Team. Other members would participate as needed. (See Table below)

To start a TIM Team, there needs to be a lead organisation or champion to bring together the various parties to create consensus on goals and objectives. In addition there will be logistics to consider (including meeting facilities), which include:

It is generally best if the TIM team champion comes from a public-safety agency, perhaps law enforcement, to encourage colleagues in other public-safety agencies to participate actively.

Effective strategies include promoting the adoption of an “Open Roads Policy” that sets a goal to clear the roadway and open the lanes to traffic as quickly as possible, for example within 90 minutes of the arrival of the first responder (the first official to respond to the scene and render assistance, such as a the police or a safety service patrol).

Some agencies’ delivery of the Open Roads Policy includes the local police and fire rescue departments and the Coroner/Medical Examiner’s Office. The Coroner’s involvement is helpful since it can grant authority to responders to remove fatalities from the roadway providing certain conditions are met (such as taking digital photographs). This avoids any delays in clearing the roadway, arising from having to wait for the Coroner to arrive and direct the removal.

In the USA members of the TIM Team are drawn from a wide range of stakeholders. Some, such as national agencies, serve more in an advisory role than an active role. Some localities also have a regional TIM Team to provide broad-based, and standardised training, and information sharing. An example is the Traffic Incident Management Enhancement (TIME) Task Force in the greater Atlanta, Georgia, USA.

|

Category |

Stakeholder |

|

National Agencies |

|

|

Regional Agencies |

Regional Department of Transportation (DOT) including as a minimum the following departments:

Sometimes the DOTs for adjacent regions are included:

|

|

Local Agencies

|

|

|

Authorities |

|

|

Private Partners

|

|

|

Associations |

|

|

Other |

|

Traffic incidents occur all the time. Events that are more serious in nature are commonly referred to as “emergency events”. Emergency Management brings together different stakeholders to respond to, and manage, emergency events.

Emergency events include events of which there is little or no advance notice – and known events for which the impacts are largely unpredictable – such as a hurricane/typhoon/cyclone. (See Security Threats)

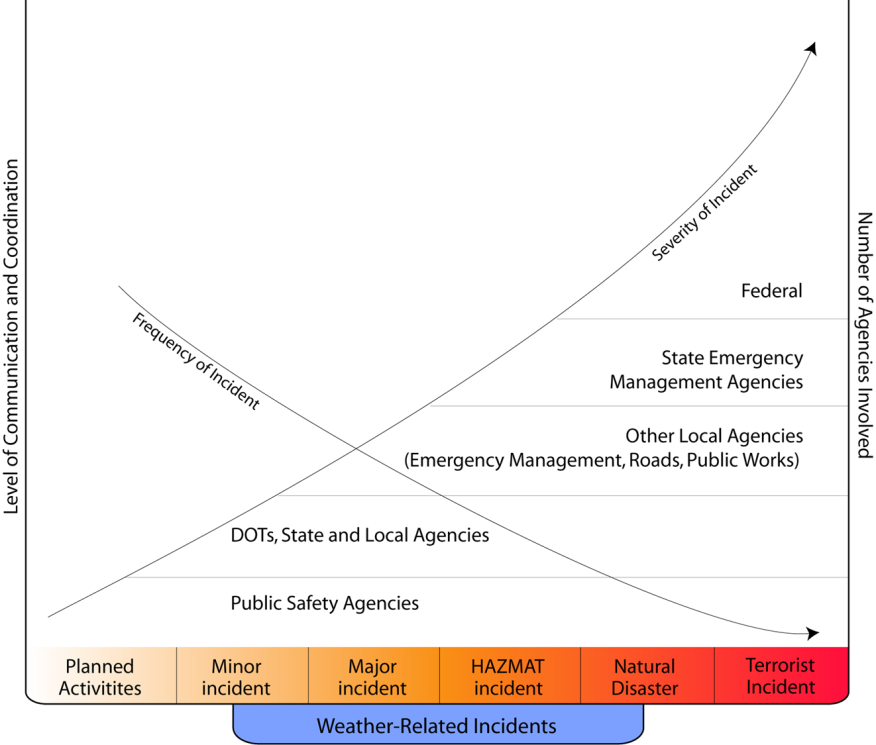

The scope or severity, of incidents is a continuum along which the responders and managers change and the team expands according to the severity of the event. The diagram below illustrates this continuum. Whatever the severity, first-line responders generally include law enforcement, fire rescue, emergency medical services, vehicle breakdown and recovery teams – and in the transport community, the road authority’s maintenance teams and mobile Safety Service Patrols. The TCC will be involved throughout as well. The involvement of agencies providing oversight and support will change as the severity increases – to include other stakeholders such as emergency managers, state and even national agencies. (See Incident Response Planning)

Normal practice is to designate an Emergency Coordination Centre from amongst the first-line responders. Often the Traffic Control Centre is well-placed to take this role. Where possible, the demarcation and allocation of responsibility for public statements, policies on the use of social media and press briefing – for different kinds of emergency, needs to be worked out in advance between those with a close interest.

Complexity of different types of Emergency Operations

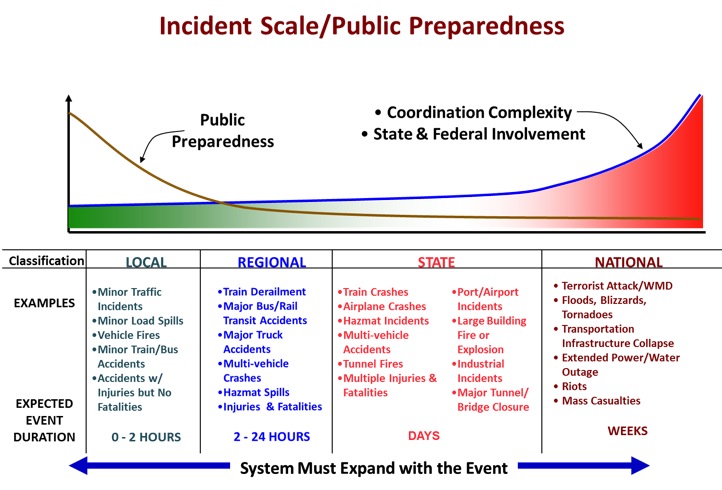

A meaningful way to view this is to consider the degree of public preparedness for the levels of incidents compared with state and national preparedness. Typical types of incident for different levels of severity are shown in the Figure below. The term “incident” applies to all levels of severity but the agencies involved and extent of their response varies and increases from the side to the .

Classification of Incidents based on Coodination Complexity and Level of Public Preparedness

The task of planning for major emergencies - the Regional/ State/National events shown in the diagram above – can be broken down into different stages:

During an emergency situation the Coordination Centre or other lead organisation has various important tasks to perform:

After the emergency has passed it is important to obtain feedback on the experience and information on any operational difficulties in order to update incident response plans:

At the national level in the USA, Federal Highways Agency has brought Emergency Management to the forefront through its Emergency Transport Operations (ETO) Programme. (See http://www.ops.fhwa.dot.gov/eto_tim_pse/index.htm)

All incidents in the USA even minor traffic collisions are subject to National Incident Management System (NIMS) procedures – albeit usually on an informal basis. (See http://www.fema.gov/national-incident-management-system)

The need for Performance Measures in Road Network Operations (RNO) is widely recognised. They have been a topic of discussion for many years but it is only recently that ITS devices provided the data necessary to support performance measures and their importance in RNO. (See Performance Indicators)

ITS can play a major role in performance measurement and will be useful to countries that do not already have strong road network performance management programmes. Performance management is important to ensure that:

Possible categories of performance measures relevant to RNO include:

A USDOT scanning tour of four European nations (England, Germany, Sweden and the Netherlands) in 2005 found a strong interest in performance-based Traffic Incident Management. Performance measures are applied in various ways, to monitor:

The following are being considered for the USA:

Traffic Officers and Mobile Safety Service Patrols (SSPs) are an important element of road network operations programmes in some countries. Transport agencies are using ITS-type systems to help them improve the efficiency of these operations.

In Europe, Asia and South America it is common for the Automobile Clubs or commercial insurance-related services to provide roadside services, such as changing flat tyres, providing a small amount of fuel, and jumping batteries. Many toll roads (also known as Road Concessions) are legally obliged to provide these services and in many cases within very tight time restraints.

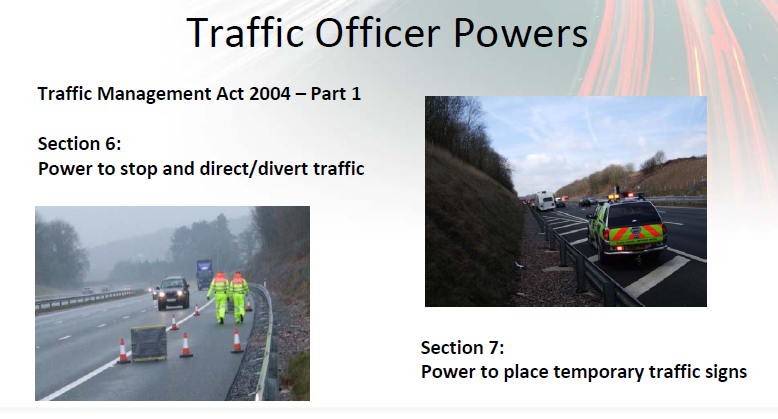

Publically operated Mobile Safety Service Patrols are also deployed. Initially they were usually purely “service patrols,” providing limited roadside assistance to vehicles having difficulty – similar to the automobile club services. Today their responsibilities have expanded. For example Traffic Officers in the United Kingdom have the authority (defined in UK law) to control the traffic flow during traffic incidents and emergencies. Their responsibilities include:

Traffic Officers have also taken on other services on behalf of the Road Authority such as:

Mobile Safety Service Patrols can now push or pull vehicles from the roadway (if permitted by law), secure and clean up minor vehicle fluid spills, set up temporary traffic controls (such as, traffic cones and flares), perform minor repairs to stalled vehicles, provide information to travellers via truck-mounted Portable Dynamic Message Signs, provide “protection” for the back of the queue and assist injured passengers. Some mobile patrols use sophisticated mobile Personal Digital Assistants (PDAs) to log the “stops” they make for both efficiency of documentation and for immediate transmission of incident data to a TCC.

Whatever their mission and capabilities, the operators’ top priorities are ensuring the safety of themselves and impacted motorists before clearing the roadway. Mobile Safety Patrols are first responders and complement the role of the law enforcement agencies. The first priority of first responders and others who work on the roadway is again, the safety of themselves and road users –above all other activities. The greatest challenge for managing risk is that with time, road workers tend to accept greater risks. This requires constant re-training.

In UK “Traffic Officers” are mobile patrols whose job it is to keep traffic moving at all times. Their role on behalf of the road authority is complementary to the Traffic Police but without replace the police responisibity for law enforcement. In UK they have specific powers to direct traffic but not to enforce the traffic law. Associated with these functions are a set of key operational capabilities and performance indicators. For example:

Traffic Officers deal with the road user as a customer. They work alongside the traffic police and other emergency services (ambulance, fire brigade and vehicle breakdown). The police retain full responsibility for dealing with public security, law enforcement and criminality.

Legal Powers of Mobile Safety Service Patrols (UK England & Wales)

Uncertainty over journey and arrival times is a major problem for travellers and companies delivering goods. ‘Smart’ travellers and fleet managers increasingly expect reliable information to help them make well-informed decisions.

Accurate, integrated and comprehensive travel and traffic information helps all road users in their journey planning decisions and how to respond to disturbances that occur on the way. In this respect it supports the task of the road network operators as well.

Travel information – and by extension route advice – is considered to be a basic service. It constitutes the lowest level of traffic management. Road users are free to decide for themselves if and how to react to the information or advice.

Investment in travel information systems by the road operator is a way of improving customer service. Information systems can also promote intermodal travel, for example by encouraging drivers to leave their cars at a Park and Ride site (typically because of localised congestion or high pollution levels ahead) and continue by public transport. Parking information systems also contribute significantly to reducing city-centre congestion and pollution by alerting approaching drivers to available spaces.

Traffic information concerns the conditions of road network use and can include predictive and current (real-time) information on traffic conditions. Stronger forms of direction include hazard messages or incident warning, and eventually control measures such as notice of road obstructions, lane control, or speed control.

Traveller aid covers all measures to disseminate predictive or current information on traffic conditions and to improve general conditions of network use. Its general aim is safety and user comfort.

Travel aid tasks are not specifically aimed at modifying traffic flows. However, when used for information purposes they must be closely coordinated with traffic management measures as they may induce users to change their travel time, route or mode of transport. In this context, they may be integrated in broader strategies related to demand management.

Generation of travel information by the network operator is a broad concept that cuts across the entire field of operations and entails several areas:

To be able to inform partners and drivers effectively, operators must first define information paths that should be coherent with the operation and management plans.

To fulfil the needs and expectations of everyone involved, the information should be timely and disseminated via all available channels and communication modes. They can be channels operated directly by the control centres (variable message signs, travel information website, RDS-TMC, traffic news broadcast etc.) or by added-value service providers who transform the information into the required data formats for smart phones and satellite navigation, and/or operate additional dissemination channels themselves. (See Traveller Services)

Provision of client-specific, personalised (enriched) information is often let to independent, value-added service providers, who extend and build on the information stream made available by the road operator. However, there should be an agreed framework for safety-related advice and direction in the absence of specific instructions from the traffic centre, in order to avoid confusion or the undermining of the set traffic policy.

The purpose of this approach for the road operator is to achieve widespread, timely information dissemination to operating partners or road users, as required. This action involves listing all components of the information system, identifying blockage points and organising or reorganising the information chain to ensure the system functions effectively. (See Systems Approach)

Successful dissemination of information is the end result of a system in which each link is crucial to success, so the operator must ensure that each link functions effectively:

Computers can be used to automate all or part of the actions described above. (See ITS & Network Monitoring)

When information for users is relayed by an intermediary – especially the media – operators must listen to and/or read the messages actually sent by the intermediary, noting the date and time sent, to assess the quality of communication.

An information system is more effective when all players involved have a good overview and a clear understanding of their role. The quality of information received by users is very closely linked to the actual systems and can actually enhance the department’s image.

The common objective of all traveller information services is to provide high quality, real-time, detailed information on transport operating conditions, including weather, so that individual travellers can make informed decisions regarding whether to make a trip, when to make it, what mode to take, and what route to take. Traveller information should be available both before a traveller begins a trip, as well as while the trips are under way, so that adjustments can be made to reflect changing operational conditions.

Traveller information can be provided in a number of ways. A summary is provided here. (See also Traveller Services and Driver Support)

In recent years the Internet has become ubiquitous as method of conveying pre-trip traveller information. Some systems offer subscribers the option of receiving alerts by mobile phone, e-mail, or other electronic methods regarding major incidents or conditions on specific routes. Telephone dial-up services remain a popular means of pre-trip and en-route information dissemination. Commercial broadcast media, including radio, cable television, commercial television, and teletext services are other commonly used methods of dissemination of travel information.

Telephone: In the United States, a nationwide three digit telephone number, 511, has been designated for traveller information services. The success of this initiative lies in issues such as the perceived accuracy, timeliness and permanent operation of the 511 service. Also, because of the variety of organisations involved (geographically, public/private, different travel modes), the issue of co-operation is the other challenge. The success of this initiative shows that appropriate institutional agreements, when designed early enough in the development process, can be a powerful lever to deploy effective ITS operations services. (See Journey Planning)

Driver information systems: by means of roadside VMS or in-vehicle units, contribute generally to a better performance of the traffic system by raising the level of awareness of drivers about the current status of the network and its likely evolution. Users of traveller information services generally agree that availability of high quality, real-time traveller information saves time, helps them to avoid congested locations and incidents, and reduces uncertainty and stress associated with travel. (See En-Route Information)

Variable Message Signs (VMS) are used to disseminate en-route traveller information in virtually all locations where electronic traffic monitoring also exists. These signs are typically placed in advance of key bottlenecks or decision points and can display fairly detailed information on location and extent of congestion, travel times, alternate routes, and downstream weather conditions (for example wind, precipitation, snow). (See Use of VMS) Highway Advisory Radio is also used, although its use appears to be declining with the growing popularity of traffic-responsive satellite navigation units and smart phone applications, which are now widespread. (See Radio)

In-vehicle navigation: En route information provided through in-vehicle navigation systems and smart phones is spreading. The VICS system in Japan, which enjoys a high market penetration of in-vehicle navigation systems, is one of the most extensive applications. Dissemination of detailed en-route information is accomplished through transmission from beacons or FM sub carrier broadcasts to the in-vehicle device. Other countries have followed Japan in deploying this kind of system. (See Advisory Systems)

Subscription services: Pre-trip and en-route information alerts provided through social media, messaging subscription services (Internet and Smartphone) is growing in popularity.

Information terminals and kiosks: Pre-trip traveller information in kiosks located in employment centres and other public places (e.g. freeway rest areas and shopping malls) are becoming commonplace, although the experience with kiosks this dissemination method has limited utility for real-time road information. Use of kiosks for public transportation information appears to be more successful. Real-time public transportation information is also successfully disseminated at transit stops in many locations using electronic signs. (see Kiosks)

Information requirements are set by network operations stakeholders, transport operators, emergency services or assistance providers and road users themselves – the latter possibly clustered in Motoring Clubs and Road User Organisations. As might be expected, there can be some variety in the geographical extent and the level of detail of the information these players need in support of their activities, or to really fulfil their travel needs.

Predictive information: This information may be on a weekly, daily or even hourly basis and concerns general traffic condition forecasts and the main anticipated disturbances. Its implementation requires:

Real-time information: This information concerns the currently-experienced traffic conditions and disturbances affecting motorists on a given route. It requires:

Real-time information also includes information to operators of customised services or navigation and guidance systems.

High quality traveller information services must be driven by high quality data on transportation system conditions and performance. Effectively fusing data into useful information from various input sources is a significant challenge that is critical to overcome if traveller information services are to be effective.

For systems that automatically post or otherwise provide traveller information based on input from traffic monitoring systems, data reliability is a critical issue. Effective automatic means of checking or filtering raw data must be in place to ensure that erroneous or misleading information is not posted.

In order to be useful to travellers, traveller information needs to be multi-modal (road and transit), and regional (crossing jurisdictional boundaries) in scope and include information about motorways and urban streets, as well as location and availability of parking.

Travellers are interested in receiving end-to-end trip information in a single query. The objective for end-to-end travel planning involves links to intercity travel providers, such as rail and air lines, to provide complete travel and routing information, door-to-door. Future enhancements for end-to-end travel may include linking to intercity travel providers, such as rail and air lines, to provide complete travel and routing information.

Information provided by traveller information services must be immediately beneficial to the user in making travel decisions. Advising travellers through a variable message sign that there is “Congestion Ahead” on the network has little value if not supplemented by information on location, extent, and severity of the congestion and potential alternate actions.