The development of ITS in Road Network Operations (RNO) can be traced back to the simple systems used to control road traffic about 50 years ago. The control system collected data about traffic flow, processed it and from the results of this processing – output commands to vehicle drivers, as illustrated by the diagram below. The data were collected from sensors that detected the passing of road vehicles, and the output commands were the "red-amber-green" indications from traffic lights.

Figure 1: A very simple ITS implementation

Since those far off days, ITS has evolved to become much larger (supports a wider selection of services) and very much more complex (they needs more and different components). ITS may now:

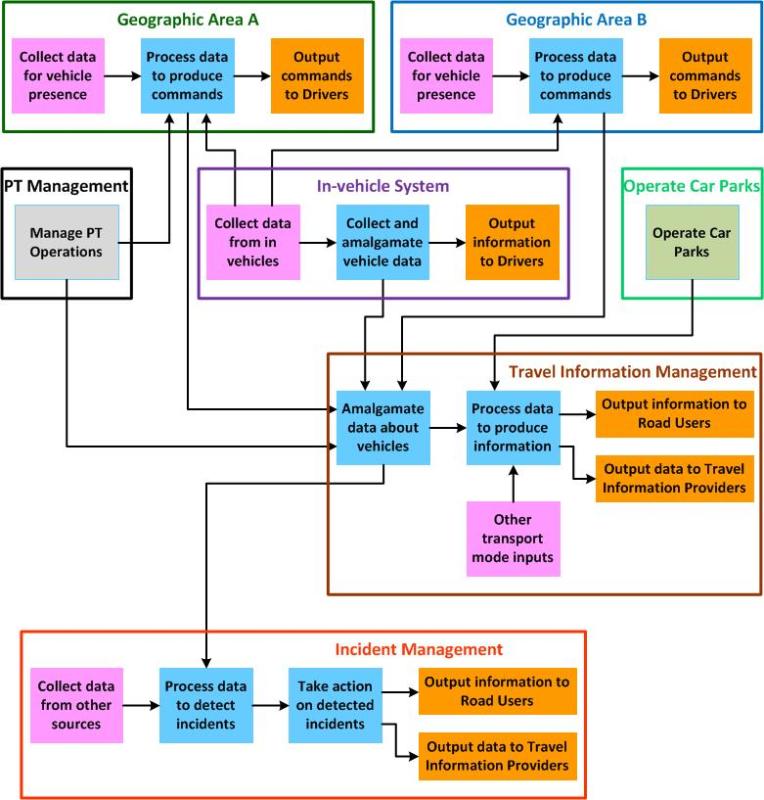

The advent of cooperative systems (usually shorted to Cooperative-ITS (or C-ITS) and called "connected vehicles" in the USA) brings further complexity that involves sharing of both collected data and the results of data processing, in which vehicles play a more active part. The system shown in the diagram above has expanded to become something similar to that shown below.

Figure 2: A complex modern ITS implementation

This example is typical of many of those being deployed in many places around the world. As the demand for ITS grows, the complexity of each implementation will increase – both in the number of services it provides and the geographic areas that it covers.

System engineering provides mechanisms that help to ensure that ITS projects of this complexity can be successfully implemented. This means they will deliver the functions that stakeholders expect and do so within timescale and budget.

One of the principal mechanisms is the ability to manage project programmes. If the programme can be properly managed then it can be completed on time and within budget.

Systems engineering programmes show the technical or engineering steps that have to be taken from the start of work through to when it is completed. In very simple terms the programme will consist of the following four steps:

These four simple steps can be applied to almost every project that implements ITS, no matter how complex, or not, each project happens to be.

Although many terms are used in systems engineering, two are used more frequently than most of the others. They are system "component" and "communications" and it is important to understand how they are used in this context.

A system "component" is the name given to any constituent part of an ITS implementation created from one or more "bits" of hardware – or a combination of hardware and software – that can be provided as an individual item. Usually, an ITS component provides a particular function, so in many ways it is a "building block" from which ITS implementations are assembled. Sometimes a combined set of components will be called a "sub-system", but depending on what it is, this name could also be applied to a single component.

The term "communications" or sometimes "communications link" is the name given to the mechanism by which data and instructions are transferred between system components, or between a component and another system that is outside the ITS implementation. It can be one or more data transmission media such as physical cables, and/or other less tangible forms of links such as wireless, microwave or infrared. In this context “communications” do not include the means of communication with the people who are the system operators and end users (travellers, drivers and freight shipping managers). These will be provided by specialist system components, such as operator interfaces or variable message displays that provide information to travellers and/or drivers. (See Engagement with ITS)

In the modern world, although most projects to implement ITS follow the four steps highlighted above, each step has become more complex. This is an increasing trend as ITS evolves particularly now that new services which are dependent upon data sharing between them (Cooperative-ITS) are moving from the exclusive province of research and development efforts into actual implementation projects. The steps in the programmes for these projects need to be expanded from the four highlighted above. Use is often made of what is called the systems engineering "V" model. Various descriptions of this will be found in resources, such as systems engineering textbooks. Simplifying some of the terminology found in these resources produces the programme illustrated below.

Figure 3: Diagram of the systems engineering

The first two steps – “Service Descriptions” and “ITS Architecture” – shown on the -hand side of the "V" are considered here. (See What is ITS Architecture?)

More information about the remaining two steps on this side and "Component Design" is provided here. (See Technical or Engineering Development)

All the steps on the -hand side of the "V", which are about testing and integration, are discussed here. (See Integration and Testing)

Some versions of the "V" model include a step called a Concept of Operations, or ConOps. It usually appears in or near the Service Description or ITS Architecture Steps at the top of figure above . The work in both these Steps can provide input to the ConOps, and further detail about this work is covered here. (See What is ITS Architecture?)

In addition to the systems engineering "V" model, other methodologies are also available to manage ITS implementations. These include "Enterprise Architecture" and the Open Group Architecture Framework (TOGAF) which are discussed in the context of ITS architecture. (See What is ITS Architecture?)

As well as the logical progression from one step to the next, it is important to include "Verification" and "Validation" as links between some of the steps.

Verification: this is a process to test whether the system component meets all the design requirements and technical specifications at each stage. What is done in one step must be compatible with the results of the previous steps. So for example, the “sub-system design and communications procurement” step may show that some of the choices made in the previous step “component specifications and communications requirements” are difficult or impossible to achieve. In this instance the ITS Architecture would have to be reviewed to see if any changes are needed to solve the problem, which if they are, will lead to a revision of the component specifications or communications requirements and some of the other outputs produced from it. (See Next Steps?)

Validation: this is the process of testing whether what has been produced as the result of each step in the hand side of the "V" model achieves the desired result, and requires that test specifications are produced. Creating a test specification should be a part of each step on the -hand side of the "V" model. If it is impossible to test the result then how will anybody know if what has been produced is doing what it is supposed to do? In this situation it may be better to review the design to see what needs to be altered to make testing possible?

Progress from one step to the next down the -hand side of the "V" should not take place unless verification has been completed and the test specification has been produced and agreed.

Sometimes, and particularly if the ITS implementation will involve several stakeholders or there are several services to be provided, it is very useful to create a statement of the "vision" that the stakeholders have of what they want to achieve. It is produced in close consultation with the stakeholders (perhaps with one taking the lead) and provides an overall picture of the ITS implementation by highlighting the following:

The "vision" should be less than a page in length and designed to be read in not more than 5 minutes. If necessary, bulleted points and diagrams should be used in preference to using lots of text. In many ways it is a "selling" document to be read by senior decision makers such as those who allocate financial budgets. But it can also be used to encourage the participation of other and perhaps as yet undecided stakeholders. The other use it has is as the precursor to the more detailed service descriptions that the stakeholders will have to produce at the start of the steps in the "V" model where the ITS architecture will be created.

(See Formulating a Programme)

Many developing countries may have little or no existing ITS components or communications. Consequently the road users, travellers and those that move goods (end users) and road managers will have limited experience of using many of the services that ITS can provide and those providing the services will have little or no experience of the on-going management of what is required to provide them. This is an important factor in deciding the scope of at least the initial ITS implementation in order to build experience of ITS and manage expectations.

Creating the "vision" statement described in the previous section can and should generate much enthusiasm about the services that ITS can provide and the benefits that they will deliver to both travellers and those that move goods. It will be tempting to include all the possible services in the first ITS implementation. This will be a mistake, a likely consequence of which is that the implementation of at least some of them will fail and/or those that are implemented will not perform as expected and hence not deliver the anticipated benefits. ITS may get a "bad press" and make it difficult to gain support from stakeholders for implementing additional services – or in the worst case – fixing those already implemented that are not performing as expected. It can also result in the development of bad relations with suppliers and/or system integrators, who will probably be blamed for the under performance of the services.

Despite what it may say in the "vision" statement, a realistic scope must be set for the initial ITS implementation. For example:

the service providing a priority system for buses will not work until the road traffic management system it needs to operate has been implemented first and proven to actually manage traffic using the road network in the way that was expected.

a trip planning service will not perform very well unless the service that collects and collates traffic data has been operating for a sufficient length of time for reliable predictions to be available for journey times, something for which several months of operation will almost certainly be required.

The important point is to set a realistic scope for the initial ITS implementation in terms of the number of services it will support. This could be included in the "vision" statement but is perhaps better put into a separate "ITS implementation strategy" document. This document should also include details of a rolling programme for the introduction of further services over a period of time – that perhaps extends to years rather than weeks or months. (See Strategic Planning and Case Studies on Finnish ITS Strategy and Seattle ITS Strategic Plan 2010-2020 )

A "rolling programme" (or "rolling plan") produces a phased implementation of ITS services in stages instead of implementing all the services at once. Each stage starts after the previous one is completed and is operating successfully.. For example, before bus priority measures are developed, the traffic management service on which they depend will be up and running and delivering benefits. A rolling programme can be implemented over months or even years, depending on the number of services and their complexities. Training and management of personnel involved in the ITS implementation can be better managed this way. Using a core team of people who manage the implementation of successive services provides continuity of knowledge and experience.

The rolling plan should not be time dependent, but driven by the proven successful implementation of the previous set of services. Thus ITS will be implemented in a series of logical steps rather than a single "big bang". Another good reason for having a rolling plan is that it will help to create a good level of interest from prospective contractors because there is the prospect of further work when extra services are added in the future.

Media and publicity can be very important for the success of any ITS implementation. Information provided to the media (radio, television, newspapers, social media, the technical journals and other platforms) needs to be handled properly. If the implementation is proceeding according to plan and the services will deliver benefits that the travelling public and freight shippers want – there should be no problem. If either of these is not the case – for example, an ITS scheme that is very costly or unpopular – then the media can become hostile. Negative publicity is more likely when the implementation runs late, is over budget or the services do not perform as expected.

It can be useful to employ a media consultant or publicist who is experienced in ensuring that information about the ITS implementation is timely and correct and is not open to misinterpretation.

The USDOT ITS ePrimer Module 2: Systems Engineering includes a very useful list of reference sources of information to aid further study of this whole subject. The Module is authored by Bruce Eisenhart, Vice President of Operations, Consensus Systems Technologies (ConSysTec), Centreville, VA, USA and is available on-line at:

The case study on the Abu Dhabi Integrated Transportation Information and Navigation System (i-TINS) provides an example of how a systems approach is applied in practice. (See Case Study: System Integration (Abu Dhabi)) There are two different aspects to managing the implementation of an ITS project, both of which are important.

The first is done by the Project Manager (PM) and covers all of the work, but with a heavy emphasis on the financial and contractual aspects. It also involves dealing with the ITS service users and customers, some of whom may not be represented by any of the key stakeholders.

A second aspect is the technical or engineering part of the work and is done by someone often called the "technical" or "engineering programme manager". This person will concentrate on the programme of technical work involved in the ITS implementation.

Project Management includes managing everything that is necessary to complete the ITS implementation to the satisfaction of its stakeholders. At the outset, project management must make sure that there is an agreed project plan in place and that the plan is followed during implementation. The level of detail must be sufficient for all participants to know what they have to do, the timeframe in which it has to be completed, any dependent project-related activities and the availability of any external resources that are required.

As part of the implementation of the project plan, project management will involve:

Acting as a "go between" with stakeholders is a two-way process. It means representing the project to the stakeholders so that they are informed about what is happening and the reasons for it. It also means representing the stakeholders to the project team to make sure that any concerns are addressed – and to deal with any changes that the stakeholders would like to see. These changes can be anything, from planned events to requirements for services – both of which can change as the project progresses during implementation.

Changes to requirements for services are sometimes collectively known as "requirements creep" and can be a natural result of changes in user attitudes towards ITS and developments in technology that make additional and/or revised services possible. (See How to create one?)

The magnitude of the project management activity will depend on the size and scope of the ITS implementation. Aside from the usual factors such as number and scope of services and transport modes, plus geographical coverage, other factors that affect the size of the activity include the numbers of stakeholders, suppliers and communications providers. Some building work may be needed, such as for a control centre, plus other work such as installation of equipment in different locations (for example the roadside) and sometimes the removal and proper disposal of existing components. None of these tasks and activities should be underestimated as some will have their own particular complexities, such as installing a variable message display over a busy part of the road network necessitating temporary traffic restrictions. All of them will need to appear as items in the project plan.

If most activities take place in the ways and at the times shown in the project plan, then the project management activity is not too onerous. It is when there are deviations from the project plan or when contractual difficulties emerge that the demands on project management increase dramatically, in scale, complexity and content. There will be times when (unfortunately) some delicate diplomacy will be needed if all the activities related to the ITS implementation are to be completed with any degree of satisfaction for everyone that is involved.

The project management activities are best carried out by a dedicated Project Manager (PM) who must be appointed before any work actually starts. Who it is will depend on a number of factors. According to the circumstance the PM may come from:

No matter where they come from, the person who is the PM has to manage all the work to implement ITS on behalf of all those involved, whether they stakeholders or suppliers, and must not favour the interests of a single entity or group at the expense of the others.

For the larger ITS implementations which are often complex and have lots of engineering content, it will be beneficial if a separate person is appointed to manage the systems engineering programme. This job can be seen as a "technical project manager" or "engineering manager", because the person doing the job may not get directly involved in the contractual or financial aspects.

The person appointed to be the technical project manager can come from

a dominant supplier, which might be the one that provides all the control and management centre components, or the person, could be from the communications provider.

if a large number of suppliers are involved, a system integrator can be appointed to which the programme manager will belong. The system integrator is often a specialist organisation and should preferably be one with a proven track record of implementing ITS and a knowledge of the particular services that the stakeholders want ITS to provide.

Whatever the origins of the person managing the systems engineering programme, they need to be able to manage all of the steps shown in the system engineering "V" model (See Systems Engineering Programme) according to the project plan.

Obviously it is important to have the numbers of staff involved in the management of the ITS implementation. For the project management part of this work, there is nothing better than an experienced Project Manager (PM), preferably with some recognised professional qualifications in project management. Experience of working in ITS is not necessary, as the PM is primarily concerned with contractual and financial matters, but knowledge of local laws and customs will be advantageous. Ideally the PM should be appointed before the "procurement" stage of the ITS implementation starts. This enables them to be involved in the final contract negotiations and to take ownership of the agreed terms and conditions. It also means that they can produce or validate the project plan at an early stage, which will enable it to have the most beneficial impact on the project. The PM should also participate in the negotiations for any sub-contracts covering specialise activities, such as building works and installation of components at the roadside.

As noted above, the PM may come from a leading supplier, or the system integrator (if one has been employed), or a large and/or dominant stakeholder, or be a complete outsider. Once the ITS implementation has been completed they can move on to other work. But if the ITS implementation needs any upgrade or improvement work, then it will be of benefit to use the same PM again to take advantage of their previous experience and any relationships they have built up with any of those who will be involved.

Similar comments apply to the person managing the systems engineering programme, the "technical project manager" or "engineering manager", except that it will be a definite major advantage if they have some previous experience of working in ITS. They should be appointed as part of the "procurement" stage of the ITS implementation, perhaps as part of the contract with a supplier, communications provider, or system integrator.

The advantage of having a systems engineering programme manager who is employed by one of the main stakeholders is that person could also be retained for work on any upgrade or improvement work that the ITS implementation requires in the future, to take advantage of the knowledge of its complexities that will have been gained from the previous work. The resourcing of staff for individual component and communications development and testing will be a matter for the suppliers and providers involved, but should be expected that the person or people involved will have some relevant experience.

For developing economies, finding the people for the project management and systems engineering programme management roles may be difficult. If expertise in either of these roles is available locally, it is more likely to be that for project management. Employing a person with knowledge of local laws and customs will be a definite advantage.

Finding a suitable person locally for the engineering programme management role will probably be more difficult. This will be particularly true if there is no local expertise in ITS related technologies and communications.

There are several consultancy companies specialising in ITS implementation that will be able to provide engineering programme managers with suitable experience. These companies vary in size from large international organisations with offices in several parts of the world, to small single person organisations. The former are likely to have a broader range of experience of implementing ITS services than single person organisations, but this does not necessarily make them any better. It is best to do some research to find out what actual ITS implementations they are working on currently and have worked on in the past to assess their experience. Also communicating directly with their actual customers will almost always provide a much better idea of how good they are.

Ideally what is needed is an organisation that is prepared to set up a local office and to recruit and train local people in engineering programme management. This will have definite advantages in that the knowledge gained from a particular ITS implementation can be retained locally and be used in any future ITS related work.

Project management is now a discipline in it its own . So it should be possible to find someone, or an organisation with the knowledge and experience to perform all the activities correctly and in the way. There are organisations that actively promote the professionalism of project management and offer access to qualifications for project managers. The largest of these is the Project Management Institute (http://www.pmi.org/) that has branches (called chapters) in most parts of the world. It has published a book called "A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge", which is now in its 5th edition.

This is the sub-system and component design, plus component development parts of the system engineering "V" model. (See Systems Engineering Programme) They are the parts that appeal to most of those involved in developing ITS technology and generate the most "excitement". This is largely because development work is where the systems are invented, developed, tested and implemented – and where people can be hands-on with the hardware and/or are able to create the software. It is also where things can go seriously wrong, which can have a very significant impact on the timescales and/or costs for the ITS implementation as a whole.

The motivation for creating new technology is often that none of the existing technologies will enable a planned service to be implemented. Also creating new technologies to replace what exists can make the implementation of a service easier and/or cheaper, so improving the benefit to cost ratio.

An example of this is the service to detect the numbers of occupants in a vehicle. Until recently, the only way to do this was to have a person located at the roadside so that they could visually check each vehicle as it passed by. Now infrared and video camera technologies have advanced to the point where a camera can do at least some of the checking.

Creating new technology is fraught with risks and must not be undertaken without proper and robust justification. This justification may be difficult to achieve, especially as most ITS implementations are often constrained by time, for instance the stakeholders want the services to be available now, or maybe in a few months, but not in a few years. What stakeholders do not want is an open-ended timescale where nobody really knows how long it will take to develop the required new technology. There are too many real life stories of ITS and other technology-based implementations that have failed because either the new technology could not be created and/or developed, or the resulting product was too difficult or expensive to produce.

Using technology that has already been developed but has never been applied in practice has less risk than using new technology. It still requires careful assessment and a good robust justification as there are many risks in going from the prototype or development phase to the production phase in technological or engineering development.

Using existing technologies that have proven track records of being successfully used in other ITS implementations provides the least amount of risk. They may also be much cheaper and there may well be a bigger choice of suppliers than for new or prototype technologies.

Design and Development starts with the component specifications and communications requirements that were created when the ITS Architecture was produced. (See How to Create One) If any currently available components and communications equipment is to be used (sometimes called "off the shelf"), then there is not much to do, other than integrate them together. (See Integration and Testing)

If something new is required, then how the component suppliers and communications providers go about producing them will be kept hidden, largely for commercial reasons. But there are a few things about which project managers, system integrators and others monitoring the ITS implementation can ask questions. The nature of the questions depends on what is being designed and developed and can be broken down into three areas: hardware, software and communications.

For many ITS implementations, no new hardware will be needed, so it should be possible to see the actual physical components being produced and to ask for evidence of previous testing, especially where this relates to compliance with regulations. If new hardware is needed then it is not unreasonable to be shown prototypes and/or watch them being tested. It may also be necessary to ensure that any local regulatory approvals that may be needed to locate and operate equipment at the roadside have been gained.

Most ITS implementations will need new software to be created, although it may not be entirely new and may involve the customisation or more serious modification of what already exists. The creation of new software is difficult to monitor because there is nothing "physical" to see. It should, though, be possible to examine the high-level software design and then monitor progress being made with the creation of modules within it, even if they are modifications of what already exists. Getting figures about the number of lines of code produced does not always mean very much on its own. It needs to be coupled with the percentage of the total that it represents.

The software supplier should have a robust and reliable code checking process in place, so that what has been produced is checked (sometimes called a "code walkthrough") before being tested. This particularly applies to software created for services that require access to/from the Internet, if the chance of unauthorised access is to be reduced to almost nothing. In this case it should be possible to carry out intrusion tests to prove that data is tamper proof and is not accessible to others not connected with the ITS implementation.

If data about planned and current traveller movements is being processed compliance with local and/or regional privacy statutes and standards must be carefully checked. Again this may require some testing, or proof that testing has been successfully completed.

If new end user interfaces are being produced, then prototypes must be made available for review and testing, preferably by representatives of the users, rather than any other group.

At one time suppliers were usually required to provide a copy of the software that they had developed for the project as part of their contractual obligations. This was either for use by the stakeholders at some point in the future, or to be held in escrow in case the supplier was unable to make any desired changes in the future. Software now is often so complex and spread across a number of suppliers and components, that this is no longer a realistic option. It also requires one or more of the stakeholders to have the necessary expertise available to use the software, which except for very large organisations is not usually the case.

Most ITS implementations will use physical communications links that already exist. In some cases, ITS may have to share these links with other unrelated services. Important questions to be asked are:

Data privacy will be particularly important when data about planned or actual traveller and freight movements is being collected and transmitted across communications links. This will be particularly important if the ITS implementation includes services that are provided by Cooperative ITS (connected vehicles). In either of these cases it is very important to check that all local and/or regional privacy statutes and standards are being followed. (See Data Ownership & Sharing)

In general the communications standards used in ITS implementations should have been produced by standards development organisations such as ISO, IEEE, CEN, ETSI and SAE. (See ITS Standards) Failure to use such standards may have the following impacts:

the communications are expensive to set up because bespoke equipment and/or dedicated physical links are needed

inter-operability with other neighbouring ITS implementations may not be possible

An example of the second point is if a bespoke communications mechanism is used for the link between vehicles and the roadside. This means that all vehicles need to have specific communications units fitted, which may be incompatible with those needed elsewhere, such as in an adjacent geographic area. In some cases this will not matter, for example because vehicles are not taken to the adjacent nation geographic area, but within continents such as Europe, Asia, Africa, plus North, Mid and South America, movement of vehicles across national borders is becoming more common

Design and development activities are probably the most important parts of the ITS implementation process, but are also the most difficult to monitor. Information about progress can sometimes be gained just by asking the questions of the suppliers and communications providers doing the work. But in the end it can be a question of trusting that suppliers and providers will do what they have said in their contracts. A way to start to build that trust is to ask other organisations that have used the same suppliers and communications providers how did their ITS implementations work out, were there any problems that were unsolved, or could have been prevented by better working practices?

Integration is the process by which all the components and communications links needed to provide the services to be delivered by the ITS implementation are brought together and tested with one another. It is often a gradual process, with groups of components being tested first before all of them are tested. When viewed from the "outside", these components appear to work as one – and their individual identities and functions may be hidden. When viewed from the "inside", the components are working together and sharing data.

Before integration can start, each of the components to be integrated must be tested on its own. This will almost always need to be done in a special environment that enables the inputs from and outputs to the world outside the component to be simulated. An advantage of simulation of the inputs is that it enables the full spectrum of possible values and/or conditions to be tested – including ones that are low probability or unexpected. For outputs, the advantage of simulation is those that are unexpected should not cause problems for other components, or for end users. Once the testing of components on their own has been successfully completed, they can be tested together, which is what the process of integration is all about.

A similar way of working must also be applied to communications links, which may pass through several physical locations and/or use several physical mediums to transfer data from one component to another. It is therefore better to test each part of the link in isolation before testing the whole link as a single entity.

The testing of the components and communications that is carried out in order to integrate them will usually go through the following stages:

Steps (1) to (3) are usually carried out at the suppliers' premises. If the stakeholders have employed a system integrator, steps (2) and (3) may instead be carried out at the integrator's premises, or at a place of their choosing. Steps (4) and (5) are usually carried out at the location where some of the components are going to operate, such as a control centre. It may be possible to increase the representation of external interfaces to include some of those for end users such as those for car parking and Public Transport. For both these Steps, in addition to a representative sample of external interfaces, communications links should either be included or simulated.

Step (6) is a trial period of operation for the ITS implementation. During this time all of its components and the communications links must be available and being used to provide all of the services the stakeholders expect to see, based on what they wrote in the service descriptions. The trial period should be sufficiently long that any particular situations for which services must be available actually take place – for example major sporting events, particular types of incidents, holiday periods, plus major festivals or New Year celebrations.

Almost all of the testing steps identified above must be described. The possible exception is Step (6), which is essentially normal operation and may require a different form of description. The descriptions of the testing in the other Steps are provided through test specifications that describe the following in detail:

The specifications for each of the tests must be written at the corresponding stage in the system engineering process. For example, the specification for the final acceptance tests must be written when the service descriptions have been created and agreed by the stakeholders. Ideally the stakeholders should write them, but in practice they are often written jointly by the stakeholders and the main supplier, or system integrator. Similarly the factory and site acceptance tests must be written when the component specifications and communications requirements have been produced. Although the stakeholders should be involved, the main supplier or system integrator will do most of the work.

For Step (6) a much simpler test specification should suffice. It may be necessary for the specification to state how acceptance tests will be conducted if any critical situations, such as sporting events, particular incidents, holidays and festivities, do not occur.

Creating good test specifications is a "must" if the components and communications links are going to work as expected. There are no short cuts to this requirement. The other thing to do is to keep a record of what tests have been done, by whom and with what results. If possible get all the tests witnessed by someone from the either the organisation that is responsible for doing the tests, or the organisation(s) that provided what is being tested. This will be particularly useful when repeats of failed tests are needed.

A necessary pre-requisite for the final acceptance that an ITS implementation has been successfully completed is the formal acceptance of the records of the completed tests. This should show that all of them have been successfully completed and that any required repeat testing has also been successfully carried out.

Where there is little or no local experience of using ITS amongst the stakeholders it is important to take one or both of the following actions:

If possible go for the second action in preference to the first. It will provide lasting benefit once the ITS implementation has finished the final acceptance tests. It will also help with the successful completion of the first few months of ITS service delivery.

It is advisable to get as many as possible – if not all – of the stakeholders involved in the final acceptance testing before the trial period of operation starts. This will help them to become familiar with what the ITS implementation will do and help to prevent the trial period of operation producing too many "surprises". Also because people from the suppliers, communications providers and/or system integrator will be present at the acceptance tests, any questions from the stakeholders can be answered much more quickly and with more authority.

A good way to get the stakeholders involved in the final acceptance testing is to ask them to provide the people to participate in the testing. So for example, if the ITS implementation includes a control centre from which the road network will be managed, then get the actual operators who will be in the centre to test the services it provides. If some of the system interfaces in the control centre are for Public Transport operators or the Emergency Services, then get those organisations to provide people to test the relevant services. For example if the drivers of Emergency Vehicles can witness the operation of "green waves" they will be able to see and understand the benefits that ITS can provide.