The term "ITS architecture" literally means, "System Architecture for Intelligent Transport Systems". As a system architecture it provides a view of how an Intelligent Transport System (ITS) implementation will look from a system design perspective. ITS architectures are primarily about data exchange and the control instructions that pass between the different ITS components and the external interfaces (operators, stakeholders and other systems). It needs to reflect the real-world constraints that operate on transport agencies and the requirements these impose on the ITS implementation. Examples are interoperability between the participating agencies and the retention of information control by the respective agencies.

An ITS architecture may show where existing organisational structures need to be modified and changed – perhaps quite radically – in order to deliver the desired ITS services. An example is a traffic control centre (TCC) that may need to exchange data with another TCC or a traveller information centre (TIC), possibly across national or language boundaries. Defining the content and minimum performance specification for this transaction matters a great deal. The ITS architecture enables the performance specification to be defined to achieve the required level of interconnection and interoperability. The choice of which specific technologies are best to use in response is a matter for the system designer.

It is not possible to present a complex system in a way that can convey all the information about the system in an understandable manner. This is reflected in an ITS architecture, where multiple viewpoints, depicting different levels of detail and different types of information are used. These viewpoints might include:

Along with development of an architecture for ITS there are other analysis requirements to consider – among them:

ITS architectures can be divided into two levels: high-level architectures and low-level architectures. This is not something that is peculiar to ITS – the distinction applies to the use of system architectures in general.

In the context of Intelligent Transport Systems, a high level architecture is the conceptual design that defines the structure and/or behaviour of the system. It specifies the functionality needed to provide ITS user services – the specifications are technology independent and the selection of individual components and communications are open. This technology independence means that suppliers have freedom to choose a technical solution that is most appropriate for the client, whilst still complying with the overall architecture.

Low-level (or component) architectures, by contrast, contain the actual designs for hardware, software, data exchange and communications. They define more narrowly the technologies required including the use of ITS standards. (See ITS Standards) A low-level architecture could be developed by the commissioning body, if they have the expertise, but it is more common for design specifications to be developed from a high-level architecture by the systems integrator or system supplier. (See Systems Engineering)

High level ITS architectures are developed to ensure that component systems can be successfully integrated and that the ITS deployment satisfies certain objectives – namely it:

They have the following characteristics:

The creation of a high level ITS architecture with optimal system configuration requires the analysis of a number of different – but crucial – aspects of the proposed deployment, as follows:

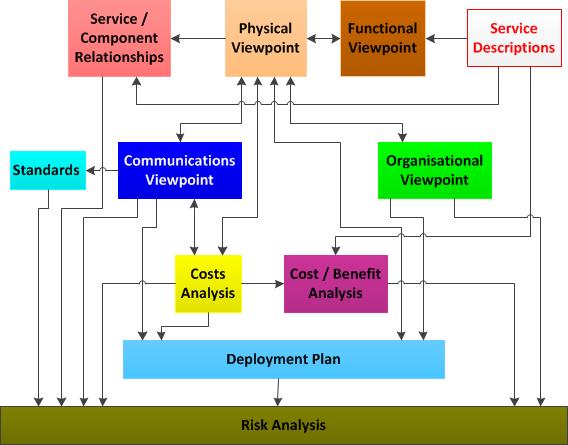

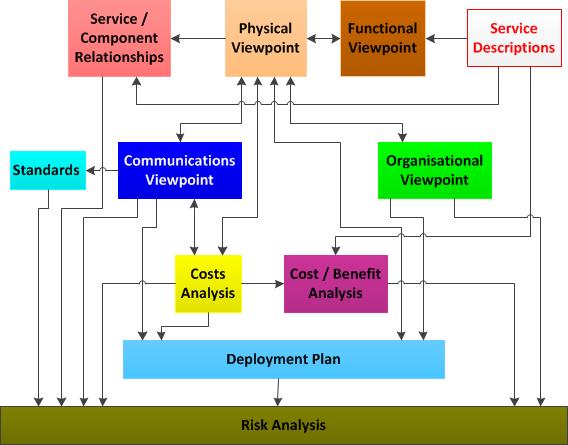

The relationship between different system viewpoints and other important aspects of ITS deployment is illustrated by the diagram below.

Relationships between different ITS architecture viewpoints and other aspects of ITS deployment

The relationships shown in the diagram are bi-directional to illustrate how results from one one aspect may influence another. For example, as a result of creating the communications and/or organisational viewpoints it can sometime be necessary to modify the physical viewpoint.

To gain maximum benefit from a high-level architecture it should be developed before any work is done to procure the components and communications needed for the ITS deployment.

Low-level (or component) ITS architectures contain the actual designs and specifications for hardware, software, data exchange and communications. They define more narrowly the technologies required including the use of and the ITS related standards that are to be used particularly for interfaces and communications. (See ITS Standards) A low-level architecture could be developed by the commissioning body, if it has the expertise, but it is more common for design specifications to be developed from a high-level architecture by the systems integrator or system supplier (See Systems Engineering) and may not always be in the public domain.

There is an analogy between the different levels of ITS architecture and the architecture for a house. In both cases the architecture may have to be expressed in various forms to suit different audiences. For the house buyer, the architecture is initially used to show how the completed house will appear and the floor plan, for example room sizes and where the toilets are located. Once the homeowner is satisfied, more detail is added so that the construction workers are provided with drawings of walls, beams and columns including their precise dimensions. Similarly, the system architecture for an ITS deployment may be expressed in various forms that are mutually consistent. High-level ITS architecture provides stakeholders with views of how the ITS implementation will appear to them. Low-level ITS architectures expand this to include the technical details that enable equipment suppliers and system integrators to implement the services. The selection of a particular architectural form depends on how far the ITS concept has ben developed and the needs of the audience at hand. The idea of multiple architectural forms is consistent with the multiple viewpoints in the IEEE standard 1471-2000, “Recommended Practice for Architectural Description of Software-Intensive Systems.”

There are two types of high level ITS architecture in common use around the world – which offer two basic but different approaches – a framework architecture and a ‘model’ architecture – both of which provide a basis for the development of ITS architectures that can be adapted to suit particular ITS implementations. Some of these ITS architectures can be specific to a class of ITS applications. This is because they support implementation of a specific service, such as traffic control centres, car park management, or public transport fleet management.

A framework ITS architecture will use a set of user-led service specifications for different ITS applications that provide a flexible basis for further refinement and development. A framework approach is particularly suited to circumstances where a ‘top-down’ universal approach is not feasible. A framework ITS architecture provides the basis for stand-alone ITS master plans to be developed at the appropriate level (national, regional or local). It can also facilitate cross-border integration and an open market for interoperable ITS services and equipment. The best known example of a framework ITS architecture is the European ITS Framework Architecture (the FRAME Architecture - See http://www.frame-online.net/). A number of countries are using the FRAME Architecture as the starting point for their own national ITS architecture developments – these include Australia, Austria, Czech Republic, France, Hungary, Italy and Poland.

Framework ITS architectures have the following advantages:

Many regions of the world have developed ‘model’ ITS architectures that are adapted to the needs and requirements of their region and institutional arrangements. They are generally more prescriptive in how ITS deployments must be rolled out when compared with a framework ITS architecture. They often contain a physical viewpoint that will define the components used to deliver the services the architecture is able to support. For example the USA’s National ITS Architecture (www.iteris.com/itsarch/) is fixed and its use is obligatory if federal financial support for ITS deployment is sought. It defines:

Other regions which have, or are, considering developing ‘model’ national architectures include Canada, Chile, Japan, Korea and Mexico. Further information is available in the review of current ITS architecture in use and/or planned from around the world available from the "Library/Other Architecture Reports" page of the FRAME web site at: http://ww.frame-online.net.

A framework ITS architecture and a ‘model’ ITS architecture both provide a structure (or template) from which ITS architectures adapted for particular ITS deployment can be generated. This allows the user the flexibility to tailor the architecture for specific deployments without losing the benefit of its common features - such as the interfaces for system components and communications. Standard interfaces are very important for consistent systems integration and will have greater importance in the future with the advent of cooperative systems ("C-ITS" for short, and known as "connected vehicles" in the USA). This is because of the need for services to be delivered in the same way, everywhere within a region, for example the USA, Europe, Australia and Japan. They make the exchange of information possible at an affordable and effective level.

ITS architectures that are adapted and customised from a framework ITS architecture have the following characteristics:

The FRAME architecture (see http://www.frame-online.net) is the best known examples of a framework ITS architecture being used as the 'master" for regional and urban ITS deployments across Europe and other countries, as well as European research projects.

ITS architectures that are customised from a 'model' ITS architecture have the following characteristics:

The US National ITS Architecture (http://www.iteris.com/itsarch/) is probably the best known examples of a 'model' ITS architecture, being used as the ‘master’ for regional and urban ITS deployments in the USA, Canada, Chile, Israel and other countries.

The choice of which particular ITS architecture development approach to use is dependent on the ultimate objective of the responsible authority or organisation – and will depend on how the ITS architecture is to be used and what is to be the starting point for its creation. In some cases the use of a 'model' ITS architecture is mandatory. For example in the USA, federal financing for ITS deployments is conditional on using of the National Architecture.

A framework ITS Architecture is generally more flexible than a 'model' ITS architecture – though both can be expanded to include extra and/or alternative services. Since framework ITS architectures are not prescriptive they can facilitate the search for an optimum component/communications solution to an ITS implementation. Using a framework ITS architecture requires some training from experts since its users need to understand the ITS architecture creation process and how to use it. (See Resources) A 'model' ITS Architecture is the least flexible since it contains restricted component configuration and communications specifications. But if no changes to the supported services are needed, they are often easier to use and do not require its users to be expert in the creation of an ITS architecture.

For economies in transition it is important to go back to basics to understand the scope for ITS to improve local transport problems and respond to user needs. These must be fully reflected in the ITS architecture’s design and specifications. This is necessary so that ITS deployments are planned and well suited to the local context. (See Deployment Strategies) It should be noted that a 'model' ITS architecture from one region may require considerable modification to adapt it so that it can be suitable for use elsewhere in other implementations of ITS.

ITS Architecture practitioners use many terms - a few are used more frequently than others. These include "component", "data", "information", and "communications" and it is necessary to make sure that everyone has the same understanding of how they are used. In addition, practitioners need to understand the difference between “logical” or “functional architecture” and “physical architecture”.

When considering an ITS Architecture, a "component" is a generalised term used for any constituent part of any ITS implementation that can be provided as an individual item. It can be considered to be a "building block" from which ITS implementations are assembled. It can be created from one or more "bits" of hardware or a combination of hardware and software. Sometimes a combined set of components will be called a "sub-system" of which there may be several in one ITS implementation.

Data about what is happening in the world outside that is relevant to the ITS implementation, arrives from many sources. (See: Basic Info-structure and Data and Information) It can represent the presence of a vehicle, data about a trip that a traveller wants to make, or details of goods and the origin and destination of their movements. The data can also be provided by other systems - such as data about the weather or details of services provided by non-road transport modes.

Information is the result of data that has been processed by one or more components within the ITS application. It can be traffic flow rates, traffic conditions, a trip plan, or details about a goods movement. It can also be the content of a variable message display and the "red/amber/green" indications at traffic signals.

The term "data communications" or sometimes "data communications link" is the term given to the mechanism through which data or information is transferred from one component to another - or between a component and something outside the ITS implementation. It can consist of one or more transmission media such as physical cable, wireless, microwave or infra-red - although their specific use may not be defined in the ITS architecture. Communications between people are enabled through an interface provided by a specialist component. For example an operator interface may provide access to several ITS services or traveller information may be provided by a variable message display.

The logical architecture or functional viewpoint depicts the functions of the ITS deployment and the associated data flows that take place between the internal components and those that link externally to people, data sources and other systems. This is defined in the formal descriptions of the services. Its development is used to identify common areas of functionality - so that the data can be shared across as many services as possible. The principle of "collect data once, share and use it many times" applies. The logical architecture is independent of any hardware or software approach.

Whilst all ITS Architectures have a logical architecture, the need to make it visible depends on the type of ITS architecture that is being created and how it is to be used. Generally speaking framework ITS Architectures need them, but customised ITS Architectures do not. How the logical architecture - or functional viewpoint - appears and is accessed will depend on which type of ITS architecture is used as the starting point for its creation.

In the context of systems engineering, the physical architecture or viewpoint shows how the functionality defined by the logical architecture (or functional viewpoint) is to be distributed amongst the system components in different organisations and locations. It is not a detailed design, nor does it include details on specific numbers of systems or equipment at particular geographic locations. Responsibility for the ownership, operation and maintenance of the system components may also be divided between different organisations.

One of the advantages of using a framework ITS architecture (such as the European FRAME architecture) is the option of exploring alternative physical architectures whilst maintaining the same logical architecture. This makes it possible to arrive at an optimal distribution of functionality in response to local requirements.

The communications architecture or viewpoint is created from the physical architecture and provides a more detailed specification of the data flows. It is at this point that the data flow characteristics are defined, such as how long the data transfer can take, how often, what security will be needed and how much data there is likely to be. The need for inter-operability can be assessed - for example enabling the same form of electronic payment to be used for all services. These detailed specifications enable a search to be made for suitable local, national or international communications standards. Existing standards should always be used wherever possible as this avoids the (sometimes lengthy) standards creation process and may make it possible to use existing telecommunications infrastructures. This means ITS deployments can take advantage of the rapid changes taking place in the telecommunications industry. Choice of communications will depend on what is available locally and the tariffs that can be negotiated with service providers. These issues need to be explored with the communications providers.

The organisational architecture or viewpoint is also created from the physical architecture and shows who will be responsible for the operation, maintenance and management of the components and communications links. It will also highlight the organisational structure that will be needed to support the ITS implementation so that it can be compared with what currently exists. This enables any changes that will be needed in organisational structure, roles and responsibilities to be described and then agreed by the stakeholders before the ITS implementation has begun.

This is an important but sometimes overlooked concept that defines the external boundaries of the ITS implementation - and where and in what form, interfaces are needed between the subsystems and the end users. As well as describing the interfaces it is also necessary to describe how the subsystems expect what is outside the ITS implementation to behave. An example of such an interface is the connection to a vehicle registration database held by the police or licensing authority which an ITS subsystem may need to access for the purposes of collecting electronic toll payments. For the ITS architecture the description of the database need only say what it is expected to do, e.g. provide contact information for a specific vehicle identity.

One important point to note is that end users that are human beings, e.g. travellers, system operators, transport planners and fleet managers, are always outside the system boundary. It is the input and output interfaces that are provided for their use that are inside the system boundary.

Copies of the European ITS Framework (or FRAME) Architecture plus its documentation and tools can be obtained at http://www.frame-online.net/. The FRAME Architecture includes support for Cooperative Systems/Connected Vehicles.

Copies of the US National ITS Architecture plus its documentation and tools can be obtained at http://www.iteris.com/itsarch/. Copies of the US Connected Vehicle Reference Implementation Architecture (CVRIA – for Cooperative Systems/Connected Vehicles) plus its documentation and tools can be obtained at http://www.iteris.com/cvria/.

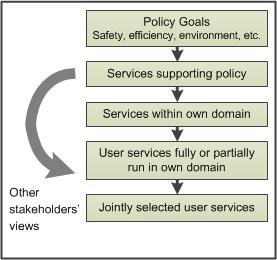

Within any single country or region, there are likely to be large differences between the set of ITS services useful for big cities and for rural areas. Many ITS applications (such as navigation and location based services) are market driven. In road network operations there are always key stakeholder groups, public authorities and private sector organisations with a part to play (for example - in motorway network management, traffic control and toll road operations). Each has different organisational areas of competence or responsibility (such as road safety, public transport, fleet logistics, policing and public security). Each has its own policy goals. Alongside there are the wider community objectives of improving road safety, transport efficiency and environmental quality. The process of stakeholder consultation is intended to take account of the bigger picture – to identify what ITS services are viable and how they should be implemented. This is outlined in the diagram below, which shows that the first step is to define the policy goals, and then identify the services that will support these goals. Stakeholders nominate the ITS services that will run either fully or partially within their own domains. These are then amalgamated to provide a set of services that have been jointly selected by all stakeholders.

Figure 21: Expression of Policy Goals in ITS Service Selection

The process of getting stakeholders involved should start by asking them to describe in their own words the services that they want the ITS deployment to include. In discussion these descriptions can then be modified so that they will support the policy goals. (See later more detailed section on "Describing the Services")(See How to Create One?) It can be very beneficial if this is done through a "stakeholder conference" so that the various groups can meet each other, discuss the options and understand each other's requirements. Often this will lead to the realisation that some of the services can be enhanced by exchanging data or information between different stakeholders.

For example, the highway network operators may be planning to deploy ITS for electronic tolling and automatic incident detection. This functionality can be adapted to give high-quality traffic and traveller information, with point-to-point journey times. An alliance between the network operators, toll road companies and the information service providers is needed to make this happen. The consortium will need to agree joint use of the ITS infrastructure, protocols for information exchange, and the data and information that they will use. All can be included in a common ITS architecture which serves the needs of all the partners.

Another example might involve the motorway network operators considering the use of ramp metering to maintain smooth traffic flow. An undesirable side effect can be long queues of vehicles that spill out onto the surrounding roads causing gridlock. Measures are needed to ensure that this does not happen. There may also be pressure to prioritise buses and coaches and other high-occupancy vehicles waiting on the ramp. The two network operators - for the motorways and the surrounding roads – need to design their traffic management policies and ITS deployments to minimise the conflict. This might involve some form of demand management with measures to encourage modal shift.

These examples emphasise the value of taking a broad view of the ITS deployment rather than each agency or organisation working in isolation. Collaborative working early on - to define the full scope of ITS deployment - means that changes can be made at relatively low cost before systems are designed and equipment has been purchased.

The benefits of creating and using ITS architectures depend on the different perspectives that stakeholders have: road network operators, transport service providers, suppliers.

The beneficiaries of ITS may be road authorities, road operating companies – who can benefit from ITS architectures in various ways:

Organisations that are concerned with the mobility of people and the movement of freight include national and local authorities and fleet operators concerned with intermodal transport – for whom ITS architectures provide the following benefits:

Suppliers may be component suppliers, communications providers or system integrators - for whom ITS architecture provides the following benefits:

An architecture approach can help all stakeholders to:

The risks of not carrying out the process of developing an ITS architecture may include:

If any of the risks are realised in practice, the costs involved in mitigating or correcting them will be significant. In some instances the only way forward is to "start again", and this time use an ITS architecture.

Despite all the benefits just described for developing an ITS Architecture, convincing the people that creating and using ITS architectures is of benefit to ITS implementation is not always easy. There are several reasons for this, the most prominent of which is that ITS architectures are seen as a constraint on commercial suppliers and system integrators. In fact they may be more liberating than a constraint because they enable stakeholders to appreciate how the ITS implementation will appear to them and what it will do for them. ITS architectures also enable stakeholders to consider all the options for the ITS implementation, including choosing to use technologies that are a best match, or if they don't exist, incentivise some research to find them.

The process of creating and using ITS architectures enables stakeholders to be much clearer about the services they want from the proposed ITS deployment – what it will do and what it will look like. As a result there will be fewer "surprises" when the ITS implementation starts up. It will help to avoid negative comments such as "I didn't know it would do that", or "I wish it didn't do that", or "I wish it could ….".

The benefits of creating and using ITS architectures need to be "sold" to the people, who are often referred to as "decision makers", meaning the people who decide that ITS will be implemented and that the finances will be made available to do it. In some instances a few of the stakeholders may also need to be convinced. So it is necessary to have a good "selling" pitch that can be tailored to suit each type of audience.

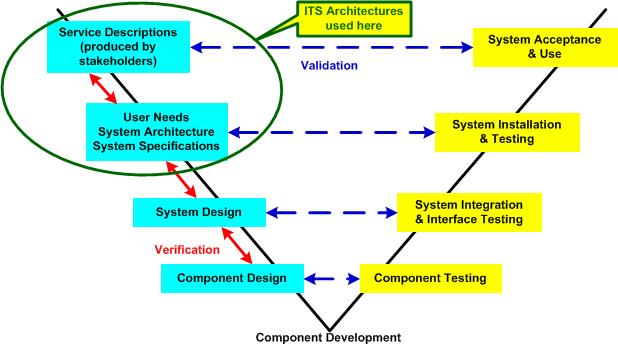

The use of ITS architectures in the ITS implementation process comes before any of the components or communications have been purchased or designed. This is because they do not contain any reference to technologies. In fact the component specifications and communications requirements produced from ITS architectures can be used as input to the procurement process. This is illustrated by the diagram below.

![[Figure 1] The use of ITS architectures in the ITS implementation process [Figure 1] The use of ITS architectures in the ITS implementation process](/sites/rno/files/public/wysiwyg/import/systems-and-standards/1439900578html_html_m30bb4bb7.jpg)

[Figure 1] The use of ITS architectures in the ITS implementation process

Organisations use various terms for the procurement process – such as "Requests for Proposals", "Call for Tenders" or "Request for Solicitations". What is important is that the architecture is included in the contract documents and is used by suppliers, communications providers and system integrators when developing their proposals. This ensures that the specification for components and communications will deliver the ITS services described by the stakeholders.

As part of their bid responses - suppliers, communications providers and system integrators can be asked to illustrate their proposals with their own system, software, hardware, data and communications architectures, all of which are low-level or component architectures. Each one can be compared with the ITS architecture to make sure that they conform to requirements and show a good understanding of what the stakeholders want.

ITS architectures are also included in the systems engineering "V" model, as illustrated by the diagram below. (See Systems Engineering)

Figure 2: ITS architecture in the Systems Engineering

There are a few other architecture methodologies that are in use around the world, which are mentioned here for completeness. Probably the most common of these are Enterprise Architectures, the Open Group Architecture Framework (TOGAF) and Object Orientated/UML Architectures. All three approaches cover more than just the architecture and go into system implementation and maintenance.

An Enterprise Architecture is a well-defined practice that can be used by organisations to guide the development of their businesses. It considers the business to be an "enterprise" and is perhaps the successor to "business architectures" that use business process modelling techniques. The concept of an Enterprise Architecture is attributed to John Zachmann when he worked for IBM in the 1980's and was responsible for the "Zachmann Diagram". It has been developed and updated several times since by organisations such as the Enterprise Architecture Centre of Excellence (EACOE at http://www.eacoe.org). As far as is known, Enterprise Architectures have never been used for ITS implementations. The creation and use of ITS architectures does fit well with the Zachmann Diagram and is part "Business Model" and "System Model", with the preparation of the service descriptions being part of its "Scope" phase.

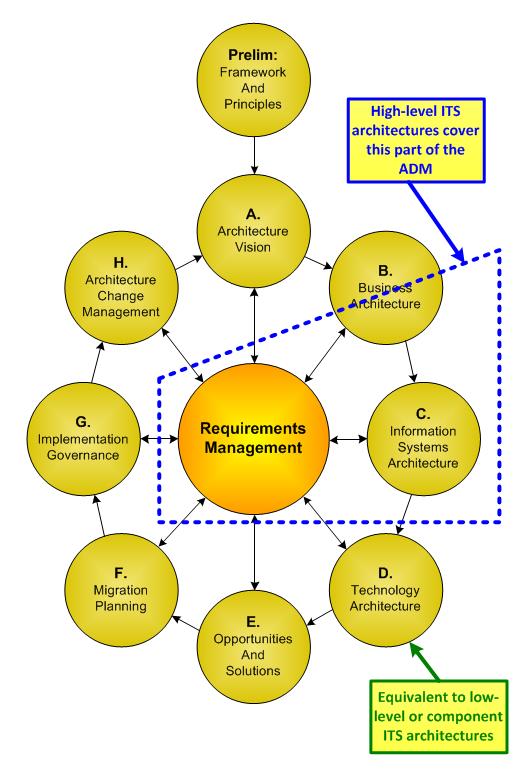

Another methodology that can be used for ITS implementation is TOGAF (The Open Group Architecture Framework – see http://www.togaf.org/). It is robust and used in many parts of the world, backed by a strong user community that offers professional certification for those that use it (TOGAF practitioners). TOGAF Architecture Development Methodology (ADM) divides architecture creation and use into several phases as shown in the figure below. The phases are similar to the steps shown in the figure on ITS architecture in the Systems Engineering "V" Model. (See Systems Engineering)

Figure 20: Relationship between the TOGAF Architecture Development Methodology (ADM) and typical ITS Architectures

Some phases of TOGAF are not covered either by high-level ITS architectures or by low-level ITS component architectures. These additional phases can cover subsequent steps in the ITS implementation process, such as procurement, installation, and operation. Including these steps within the architecture has the advantage of delivering both the actual solution, as well as closing the loop and updating the ITS architecture.

More information about the use of TOGAF in the Australian National ITS Architecture project can be found at: http://www.austroads.com.au/road-operations/network-operations/national-its-architecture#

Object orientated methodology has been long established for software and system design and is almost always illustrated using the Unified Modelling Language (UML). So far as is known only two ITS architectures have adopted it: the ITS architecture developed by ISO TC204 in 1998 and the Australian ITS Architecture, which was developed a few years later. based on ISO.

The ISO ITS architecture has largely remained untouched since it was produced and may now be lacking in support for many of the ITS services used today. The Australian ITS Architecture was also little used. In the last few years, Australia has begun development of a new Australian National ITS Architecture. It is following the route taken by most High-Level ITS Architectures (See What is ITS Architectures?) that have been developed around the world and using the methodology described in this module.

It is probably true to say that the object orientated methodology is inappropriate for use by people outside of the IT industry since it requires practice to become familiar with it. This methodology is more appropriate for low level (or component level) ITS architectures that are used by system and software developers.

Many developing economies will have little or no experience of ITS. This means that there will be very few existing ITS deployments and where they do exist, they will often be standalone having no links with any other systems. Thus any new ITS implementation will be starting from what is virtually a "greenfield site". In this situation, creating and using ITS architectures is virtually a "must" since it provides the greatest opportunity for assessing all of the options for component and communications configurations. This should be done without the influences of suppliers and providers, who will inevitably be keen to sell their own products, but should take account of what standards are available, particularly for communications.

Creating and using ITS architectures will provide the opportunity to specify components and communications that will produce an ITS implementation that is "open" – one that uses open, or publicly available, standards to which anyone can conform. This will in turn widen the potential supplier and provider base, in other words make it easier for a broader range of companies to tender for the supply of components and the provision of communications. This will apply not only to the initial ITS implementation but also to future expansions and upgrades, thus avoiding the trap of being "locked into" a particular source of components and communications.

There are two ways to create ITS architectures, either starting from nothing or by modifying an existing ITS architecture. Both approaches are directly related to the type of architecture from which they will be created (which could be either a “model” architecture such as the US National ITS Architecture or a framework architecture such as the European FRAME Architecture).

There has been much experience with ITS research, development and deployment - which is captured in two widely used architectures that exist today. The US and FRAME architectures have evolved with ITS over the past 20 years. Both have been refined to keep pace with ITS development and deployment in the two regions – and domestic and international standards have been developed, based on them. It would be very expensive to approach a new architecture development starting "from nothing". Adapting or adopting ITS functional definition from existing architectures offers a cost effective approach for a new architecture definition provided that the local user needs, institutional set-up and transport context (such as the package of user services, modal choices and traffic mix) are addressed. These may vary considerably from the assumptions inherent in either the US or FRAME Architectures.

The two ways of creating an architecture (start from nothing or adapt an existing architecture) share a common starting point. This is the description of the services that the ITS deployment is to provide - which has to be reflected in the ITS architecture. The process can be summarised as follows:

Service Descriptions -> User Needs -> Functional Definition -> Physical Partitioning -> Communications -> Linkages to Standards.

In the process shown above, any detailed concepts about how the services are to be delivered will be part of the “User Needs”. They are often referred to as “operational concepts” and “operational requirements” and are constraints that need to be applied in the ITS implementation process following the creation of the ITS architecture. Examples are a service “must be available all day every day (i.e. 24/7)”, or a service “must be available in the same way everywhere”. To highlight their importance these concepts are best captured in a Concept of Operations (ConOps) document that contains descriptions of how the services will actually work. To do this, the document requires inputs from some of the architecture viewpoints created later on in the ITS architecture creation process. So whilst creation of the ConOps document may be started early on in this process, it cannot be completed until nearer its end. (See Next Steps)

Describing the services that the ITS implementation is to provide is the first and most important step in the creation of ITS architectures. It is the foundation for all subsequent architecture development activities. (See Resources)

Generating the description of each service is best started by having a dialogue between the architecture team and those who want the service provided – usually referred to as stakeholders and who may be any of the following:

The process of engaging with stakeholders involves a sequence of activities:

The development team will need to meet key stakeholders, either individually, or as a group such as "road users", or a "quality circle." (See Planning and Reporting)

Another group to be consulted with be policy makers so that the services the ITS architecture provides will support national and regional policies. (See Why create an ITS architecture?) If a "vision" statement for the ITS implementation has been produced – those who developed it will need to be consulted. Another alternative is to select stakeholders by what they do (their function) – such as:

At these meetings just asking the attendees what ITS services they would like to see may not produce any real detail on the services the stakeholders want, from which the stakeholder aspirations can be produced. Often more will be achieved by discussing what each stakeholder does, any problems they currently have (for example delivering policy outcomes or developing user services) and how they see their activities will develop in the future. A useful question to ask is “what will be the organisation's main activities in 3-5 years' time?” This type of question will focus discussion on what ITS features or facilities are desirable in the future.

The architecture team will need to be represented by at least 2 people - one to lead the discussion and the other to take notes. Each meeting should be planned to last long enough to explore the issues in depth (often between half a day and a whole day depending on the number of attendees). How many meetings will be needed depends on the number of stakeholders and whether the team meets them individually or in groups. The advantages of either option are:

When all the meetings have been completed the architecture team will need to produce a report that describes each of the services the stakeholders want (Service Descriptions) included in the ITS implementation. The end result must be an agreed set of service descriptions that the stakeholders are prepared to endorse through their commitment to supporting the ITS implementation.

This approach creates the ITS architecture as something new, starting only from the service descriptions produced in conjunction with the stakeholders. This approach is not recommended for the following reasons:

There are a few specialist software tools available for ITS architecture creation. The two most widely used are probably System Architect from IBM and the Mega Process business modelling tool from Mega International.

Starting from an existing ITS architecture is normally the best way to create a new ITS architectures It builds on the experience gained from the creation of the existing ITS architecture – with the benefit of assistance being available from one or more sources if needed. There are two widely used options for creating ITS architectures in this way:

An ITS architecture that has been developed for one set of circumstances can be adapted and used as a starting point for other ITS architectures elsewhere if the circumstances are similar. For example an ITS Architecture created for one region might be successfully adapted to another region with suitable modifications. In general the ITS architecture development process follows the sequence:

Service Descriptions -> User Needs -> Functional Definition -> Physical Partitioning -> Communications -> Linkages to Standards.

The “operational concepts” and “operational requirements” explained above should be included in the user needs and will be important in the later steps in the ITS implementation process. They should also be covered by the Operations document. (See Next Steps)

The above process applies to any the creation of any ITS architecture. FRAME and the US Architecture both provide inputs to each of these process steps in different ways. Where the starting point is the:

Before a choice can be made between the two starting points, it is important to have discussed and answered the following questions:

The answers to these questions will help to decide which method is to be used to create the ITS architecture. Whatever the answers, use caution if the "Start From Nothing" approach is used because it will require a heavy commitment of resources over a long period of time without the benefit provided by an existing ITS community.

Choosing between the two options to “Adapt an existing ITS architecture” is a balance between the following issues:

If the services described by the stakeholders have a "US flavour" then the US National ITS Architecture is the obvious starting point – particularly if it is used for a single ITS implementation. In this case it is only the content of the services that is the deciding factor.

If there is not a good match between the services selected by the stakeholders and the US User Services or Service Packages, then the FRAME Architecture is a better starting point as it will be easier to adapt.

Developing economies may have little or no existing ITS components or communications. This means that the ITS architecture will be describing what can be viewed as a "greenfield" ITS implementation. It is tempting to think that the best way forward is to adopt the "From Nothing" approach. This is not necessarily true for reasons of cost, complexity and the lack of support from an existing ITS architecture user community.

A case study is available on the design of the Abu Dhabi Integrated Transportation Information and Navigation System “i-TINS".(See Case study)

Before starting work on creating the ITS architecture it is very important to estimate the resources that will be needed. The best way to do this is to split the work of creating the ITS architecture into three phases:

The numbers of people needed for each phase will depend on the number of stakeholders and the expected scope of the services that the ITS implementation is to provide.

Experience has shown that it is impractical to have only one person at the meetings with stakeholders to enable the Stakeholder Aspirations to be captured (See How to Create One?). This is because it is virtually impossible to direct the course of a meeting and take meaningful notes of what is said at the same time. Stakeholders can be encouraged to submit written descriptions of the ITS services they need or aspire to (“Stakeholder Aspirations”), but holding stakeholder meetings, either individually or in groups is a better way to gather this type of information. An accurate record of what is said at these meetings will be an invaluable aid to developing the detailed Service Descriptions. Discussions with stakeholders before the architecture is developed are likely to produce “Stakeholder Aspirations” rather than strict, specific Service Descriptions which need to be refined by the Architecture Team before starting work on creating the ITS architecture.

At least two people will be needed for each stakeholder meeting – one to lead the discussion and the other to take notes. If a large number of stakeholder meetings are needed, it may be necessary to deploy teams of two people each, so that meetings between non-related groups of stakeholders can be held in parallel. For most ITS implementations, the time taken to produce the service descriptions to the level of detail required, will be about 6 months, since it is usually necessary to talk to stakeholder representatives whose diaries are often very full.

Previous experience suggests that having more than one person working on the actual creation of the ITS architecture does not save time or effort and may produce inconsistencies within it. The best solution is to have one person creating the architecture and at least one person to review it.

If the ITS architecture is be created from either the US National ITS Architecture or the European FRAME Architecture, then the time required should be relatively short - about one month should be sufficient and includes the creation of the physical viewpoint. If the "Start from Nothing" approach is taken, then the time taken will be considerably longer – probably about 9 months for a small scale ITS project and up to 2 years for a more extensive architecture.

Creating the different viewpoints for an ITS architecture (physical, communications, organisational) and analysing other aspects of the ITS implementation (deployment, cost-benefit, risk analysis) (See What is an ITS Architecture) can be undertaken by several people – if necessary working in parallel. The possibilities for parallel working can best be seen from the diagram below.

Relationships between different ITS architecture viewpoints and other aspects of ITS implementation

Many of the links are bi-directional because work on one view or viewpoint can affect the contents of a previously created view or viewpoint. So for example, physical and communications constraints identified by work on their viewpoints can require changes to the way that the functionality is partitioned in the functional viewpoint.

It is tempting to think that some ITS architectures will not need all of these viewpoints or an analysis of the other aspects, for example when the ITS architecture for a research and development project. In practice this is not true. What will vary is the level of detail that is needed, so that for example, an ITS architecture for a single service may require less detail in its organisational viewpoint, plus a much simpler treatment of deployment, cost/benefit and risk.

To create all of these viewpoints and other outputs three people will be needed and they should be able to complete the work in three months. Obviously if less detail is required then the amount of effort reduces, which can be expressed either as a reduction in people or in the time taken.

Overall estimate of resources required to create an ITS architecture

The following table summarises the three phases of ITS architecture creation.

|

|

Phase |

Number of people |

Duration (months) |

|

|

Number |

Title |

Minimum |

Ideal |

|

|

1 |

Creating the service descriptions |

2 |

up to 4 |

up to 6 |

|

2 |

Creating the ITS architecture |

1 |

up to 3 |

1 |

|

3 |

Carrying out the follow-on activities |

2 |

up to 3 |

up to 3 |

The conclusion from the table is that between 2 and 4 people will be needed for a period of up to 10 months. It is advisable for each team member to work on the three phases of architecture development rather than focusing just on one.

Once the ITS architecture has been created, it needs to be maintained and kept relevant if it is to continue to serve a useful purpose. The resources required to do this should be small, with two people needed for a period of about 6 months every 12-18 months – but this will depend on the size of the project. The need to update the ITS architecture will depend on the speed of the evolution of ITS and the stakeholders’ need for implementing new ITS applications.

When allocating resources, it is helpful to keep in mind the long term situation and the need to keep the ITS architecture consistent with the continual evolution of ITS. For large ITS architectures, such as those with several different types of service (for example, traffic management, public transport and tolling) it will be cost effective to employ the same person to create and maintain the architecture. The dividends will be reduced staff resource time because of retained knowledge, which in turn can be translated into reduced costs. Stakeholders will be dealing with someone who knows about the ITS architecture, which will inspire them with confidence.

It is possible that there will be no suitable local expertise to create the architecture but dependency on the use of consultants will be expensive. A better plan may be to train at least two locally-based people to create the ITS architecture and carry out the maintenance work – drawing on a mentor for help and advice. The locally based people do not have to be software or hardware engineers - in fact it is probably better if they are not. Computer literacy, willingness to learn and enthusiasm are the prime requirements, with some knowledge of ITS being a great help. Local staff will be better placed to appreciate what the stakeholders want from ITS.

One of the two main starting points for creating a new ITS architecture from an existing ITS architecture is the US National ITS Architecture.

US National ITS Architecture Turbo Architecture tool provides facilities that enable users to tailor and expand the architecture content to meet the needs of their particular ITS implementation. The adaption process is described in parts of the “Help” facility for the Turbo Architecture tool, but users may find it helpful to obtain specialist assistance and advice before starting.

Using the US National ITS Architecture to create the ITS architecture that will support the services agreed with the stakeholders means taking the following steps.

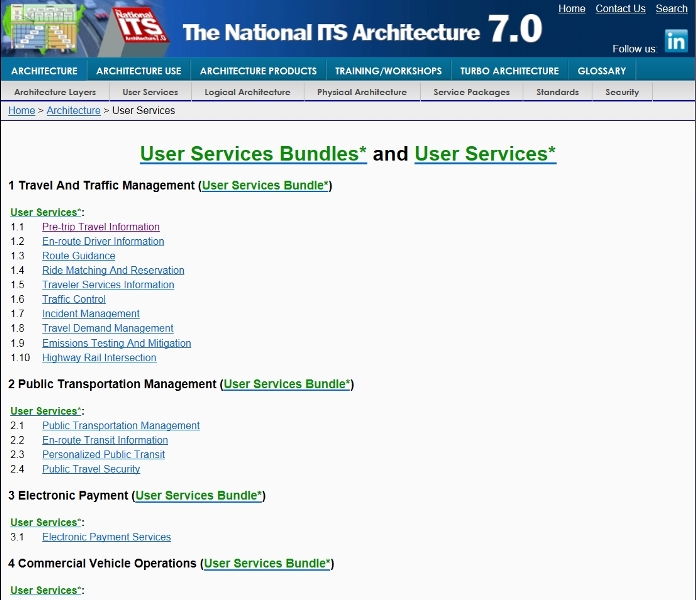

Step 1. On the US Architecture website (http://www.iteris.com/itsarch/) select the "User Services" tab. This will open a new window that displays a list of User Service Bundles and User Services, as shown below. User Service Bundles, are groups of User Services for similar ITS supported activities, such as Travel and Traffic Management shown below.(Click + to show)

Figure 6: US ITS Architecture website opening screen shot

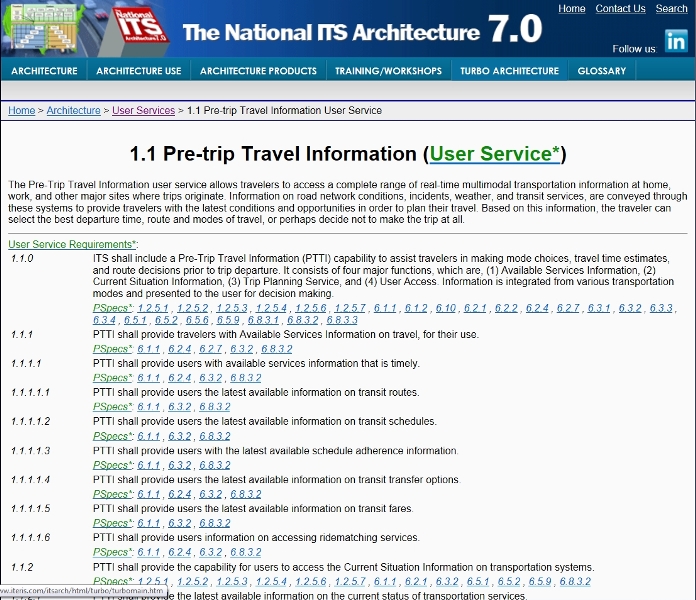

Step 2. Clicking on a User Service will open another window containing the overall description of the User Service and descriptions of each of its constituent services, plus where they are used as shown below. The last piece of information can be ignored as it will be taken care of by the Turbo Architecture tool, illustrated below. (Click + to show)

Figure 7: US ITS Architecture website user services page

Step 3. Create a spread sheet, then copy and number the service descriptions approved by the stakeholders (See How to Create One) into the two hand columns. Mark the columns to the with headings for the User Services numbers and descriptions that match each service description, plus (optionally) an extra column for assumptions, cross references to other matches, or comments.

Step 4. Go through the service descriptions and find the matching User Services. Copy into the spread sheet the number and text of the User Service(s) into the appropriate row(s) opposite the Stakeholder Service description that they match, duplicating rows if more than one User Service is needed to completely match a Stakeholder Service description. The table that is produced should look something like this:

|

Stakeholder Services |

Matching User Service |

Comment |

||

|

Number |

Description |

Number |

Description |

|

|

2.1 |

The expected town expansion of 10-15k new homes and extra shopping facilities must be supported with suitable traffic management and public transport services. |

2.1.0 |

ITS shall include a Public Transportation Management (PTM) function. |

|

|

2.1 |

The expected town expansion of 10-15k new homes and extra shopping facilities must be supported with suitable traffic management and public transport services. |

1.6.0 |

ITS shall include a Traffic Control (TC) function. Traffic Control provides the capability to efficiently manage the movement of traffic on streets and highways. Four functions are provided, which are, (1) Traffic Flow Optimization, (2) Traffic Surveillance, (3) Control, and (4) Provide Information. This will also include control of network signal systems with eventual integration of freeway control. |

|

|

2.2 |

There is an overall need to optimise the use of the existing road infrastructure, improve Public Transport services, and improve the facilities for cyclists and pedestrians. |

1.6.1 |

TC shall include a Traffic Flow Optimization function to provide the capability to optimize traffic flow. |

|

Step 5. From experience it is a good idea for the Architecture Team to carry out this work individually and then compare their results at the end. The points of agreement can be accepted and the points of disagreement debated. At the end a table will have been produced showing the agreed matches between the Stakeholder Service descriptions and the User Service Descriptions.

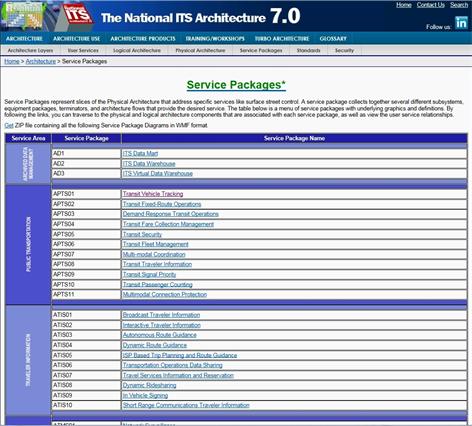

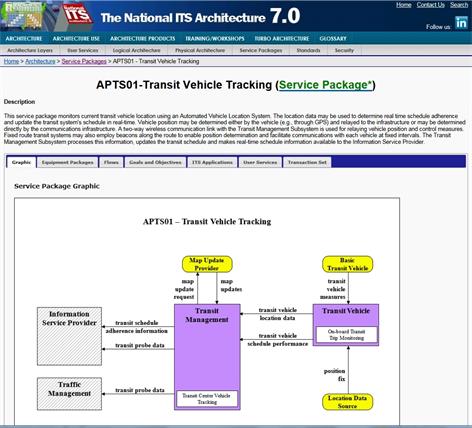

Step 6. An alternative method for Steps 1-4 is in Step 1, to select the "Service Packages" tab which will open a new window that displays a list of the ITS service packages that the US Architecture supports. (Click + to show)

Figure 7.1: US ITS Architecture website Service Packages page

Step 7. Clicking on a Service Package will open another window containing its description and a diagram of its constituent parts. There are separate tabs that give access to a variety of other information about the selected package. (Click + to show)

Figure 7.2: US ITS Architecture website Service Package description page

The spreadsheet created in Steps 3 and 4 will should have "Matching Service Package" as the title of columns 3 and 4, which should contain the identities of the selected Packages.

Step 8. Do not be afraid of deciding that not all parts of one or more Stakeholder Service descriptions can be matched to one or more User Services or Service Packages. Both of these are based on the way that ITS is expected to be implemented in the USA.

Step 9. If you are unhappy with the way that the Stakeholder Service descriptions have been matched to the User Service descriptions or Service Packages, then the US National ITS Architecture needs to be modified to accommodate the service(s) you want to provide. If you need to do this then you should continue with Step 9 and use the Turbo Architecture tool help facility to find the guidance that will show you how to modify the architecture to include extra service packages and their associated elements.

Step 10. The next step is to download the Turbo Architecture tool from its page on the US ITS Architecture website. A link to this is provided by the "TURBO ARCHITECTURE" tab at the top of every webpage and it is recommended that you read this page before commencing to download the Tool. Downloading the Tool will also include a copy of the database it uses that contains the details of the US National ITS Architecture.

Step 11. Although the Turbo Architecture Tool is fairly easy to use, before doing so it is very wise to complete one of its training courses, some of which are available on line. The details of what they contain and how to participate are also available through the US ITS Architecture website with other training resources at the top of every webpage under the "TRAINING/WORKSHOPS" tab.

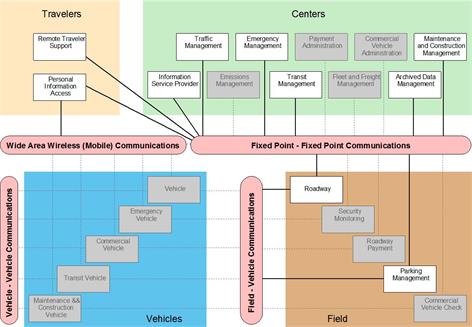

The Turbo Architecture Tool provides a step by step development of stakeholder needs in terms of the services that they want ITS to deliver. These are traced to physical subsystems and functional requirements. It is also possible to tailor the information flows to suit particular user requirements, provide linkages to standards, and identify stakeholders. This is all contained in a single tool and the products are interrelated, producing diagrams, tables and – for final production – webpages and documentation that make the architecture available to all stakeholders. An example of a diagram showing the subsystems and their interconnections for a typical ITS implementation is provided below (Click + to show).

Figure 8: Example of an interconnect diagram produced by the Turbo Architecture tool

In the diagram above the items in "grey" are subsystems in the full US National ITS Architecture that are not being used in this example.

The Turbo Architecture tool can be used to produce further details. These include:

All of the above are provided using pre-prepared templates, which will contain the selected information. Each table and report can be edited to change the layout or format to suit individual organisation requirements. Examples of these outputs can be seen by opening the "marinara" example, which is included in the Turbo Architecture program files.

A case study on the development of a national ITS Architecture for Chile is available. (See Case Study)

Further information about US National Architecture and details of training courses can be found from the US National ITS Architecture website at: http://www.iteris.com/itsarch/. This also provides a "Contact Us" link at the top of each web page for those with specific questions.

A fully comprehensive guide to creating ITS architectures from the US National ITS Architecture can be found in the US DoT publication, "Regional ITS Architecture Guidance , Developing, Using and Maintaining an ITS Architecture for your region", available for downloaded as a PDF file free of charge from the US Department of Transport website at: http://www.ops.fhwa.dot.gov/publications/regitsarchguide/raguide.pdf

One of the two main starting points for creating a new ITS architecture from an existing ITS architecture is the European ITS Framework Architecture, commonly known as the FRAME Architecture. This example is based on the work done to create an ITS architecture for a local road authority in the UK (the County of Kent) who has given permission for its use in this web resource.

To use the FRAME Architecture to create an ITS architecture that will support the services agreed with the stakeholders will involve taking the following steps.

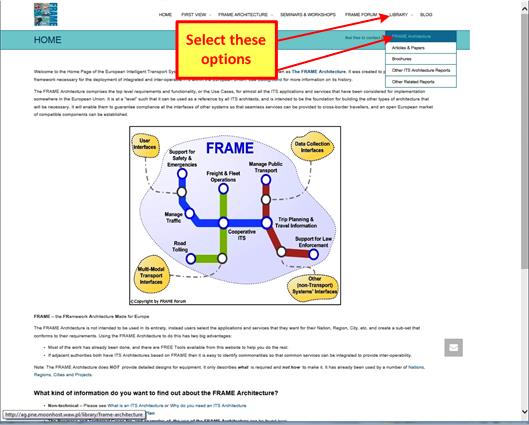

Step 1. Visit the FRAME Architecture website (http://www.frame-online.net/) and select the "Library" tab and click on "FRAME Architecture" as shown below. (Click + to show)

Figure 9: FRAME website opening screen shot

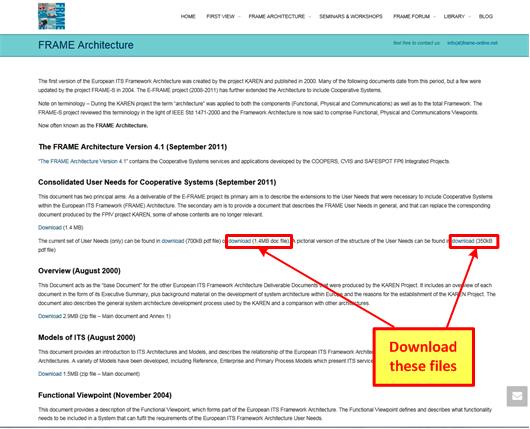

Step 2. On the next web page that is displayed, download the User Needs (1.4M doc file) plus the pictorial version of the structure of the User Needs (350kB pdf file), as shown below, and save both files. (Click + to show)

Figure 10: Selecting FRAME User Needs files to download

Step3. Create a spread sheet, then copy and number the Service Descriptions generated by the architecture team (and approved by the stakeholders (See How to Create One?),into the two hand columns. Label the columns to the with headings for the FRAME User Needs Numbers and User Needs Descriptions that elaborate each Service Aspiration, plus (optionally) an extra column for Assumptions, Cross References to Other Matches, or Comments.

Step 4. Go through the Service Descriptions and find the relevant FRAME User Need Descriptions in the "1.4M doc file" downloaded in Step 2. Studying the table of FRAME User Needs will help to identify the Groups of User Needs to consider. For the moment at least, ignore the Group 1 User Need Descriptions as these are "general" and can be used later, in the procurement process. These relate to issues such as adaptability, continuity, data quality, privacy, robustness, safety, security and user friendliness - all of which will need to be addressed in one way of another by various parts of the ITS implementation.

Copy into the spread sheet the Number and Text of the FRAME User Need Descriptions into the appropriate row(s) opposite the Service Aspiration to which they are relevant, duplicating rows if more than one User Need Description is needed to completely match a Service Aspiration. The table that is produced should look like this:

|

Stakeholder Services |

Matching User Need (FRAME) |

Comment | ||

|

Service Number |

Service Description |

FRAME Number |

User Need Description |

|

|

2.1 |

The expected town expansion with 10-15k new homes and extra shopping facilities must be supported with suitable traffic management and public transport services. |

10.1.0.1 |

The system shall provide effective and attractive PT. |

|

|

2.1 |

The expected town expansion with 10-15k new homes and extra shopping facilities must be supported with suitable traffic management and public transport services. |

10.1.0.3 |

The system shall be able to assist PT operators in planning for the optimum use of existing resources to meet the demand. |

This User Need also called up by service 2.2. |

|

2.2 |

There is an overall need to optimise the use of the existing road infrastructure, improve Public Transport services, and improve the facilities for cyclists and pedestrians. |

10.1.0.3 |

The system shall be able to assist PT operators in planning for the optimum use of existing resources to meet the demand. |

This User Need also called up by service 2.1. |

Step 5. From experience it is a good idea for the Architecture Team to carry out this work individually and then compare their results when all the Service Aspirations have been processed. The end result will be consensus on a table showing the agreed list of User Need Descriptions that match the stakeholders’ Service Aspirations.

Step 6. Do not be afraid of deciding that not all parts of one or more the Service Descriptions can be matched to one or more User Need Descriptions. If this happens, the FRAME Architecture can be extended so that it provides the support for these services. How to do this is described in Part 3 of the FRAME Selection Tool Reference Manual, which is available from the same web page as the tool itself – see Step 10 and also Step 7 which follows.

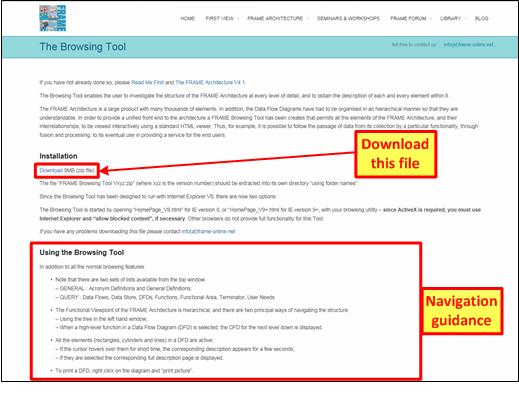

Step 7. If as a result of your work in Steps 5 and 6 you decide that you do need to extend the FRAME Architecture, it is essential to see what is in it. To do this on the FRAME website click on the "FRAME Architecture" tab and select "The Browsing Tool" option, which will show the web page from which the Tool can be downloaded. (Click + to show)

Figure 11: FRAME Browsing Tool download page

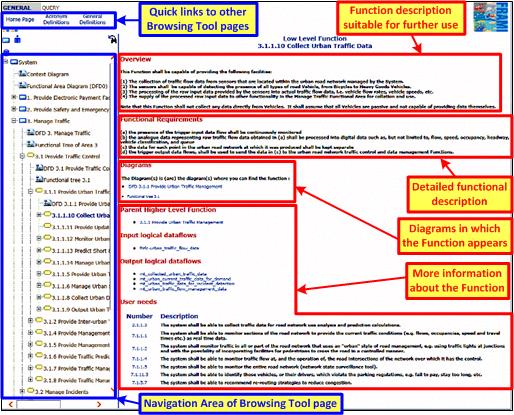

Step 8. The Browsing Tool will need to be set-up by following the instructions on the web page, which also explains how to run the Tool. When run, the Tool will initially display its home page, from which the contents of the FRAME Architecture can be viewed. A sample of its display for part of the functionality is shown below (Click + to show) Browsing Tool pages for the data flows and data stores will be similar in appearance, and it is also possible to display data flow diagrams (DFD's).

Step 9. Navigating through the Architecture can be done using the Navigation Area on the or through the links provided by the "blue" coloured text in the main part of a page. Guidance about how to navigate through the FRAME Architecture using the Browsing Tool is also provided on the home page and in the FRAME web page referred to in Step 7.

Figure 12: Screen shot of FRAME Browsing Tool page

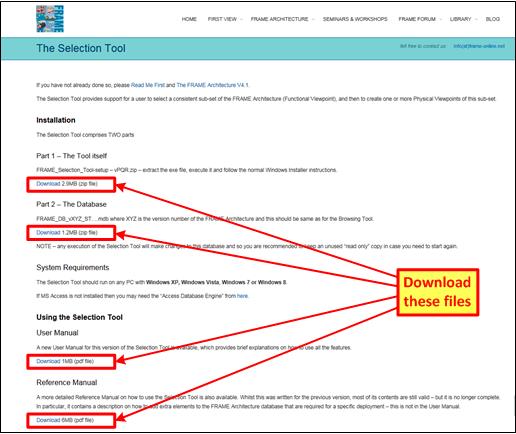

Step 10. Once you are happy with the way that all the service descriptions have been matched to the User Needs, download the FRAME Selection Tool. To do this, click on the "FRAME Architecture" tab at the top of the page and on "The Selection Tool" in the drop down list that appears. The web page that appears is shown in the diagram below and it provides instructions for downloading the Tool, the database it uses, its User Manual (needed for Steps 1-13) and the Reference Manual (needed for Step 6). (Click + to show)

Figure 13: FRAME Selection Tool download page

Step 11. Once the Selection Tool has been set up, the User Manual will provide guidance about its use to create ITS architectures. This involves selecting the FRAME User Need Descriptions identified in Steps 4 and 5 and using the Tool to include the functionality needed to support them (functional viewpoint), the physical viewpoint and - if needed - the organisational viewpoint.

The Selection Tool will perform checks on the logical consistency of the functionality that is included from the User Needs you have identified in Steps 4 and 5. It will expect you to resolve any inconsistencies by adding/deleting functions, data flows, data stores and terminators. If you haven't already downloaded the Browsing Tool in Steps 7 and 8, follow the instructions above. It is essential to use this Tool to study the FRAME Architecture to see what is causing the logical inconsistencies.

Step 12. The Selection Tool allows several physical and organisational viewpoints to be created for one functional viewpoint, which is part of the process of finding the optimum configuration (See Next Steps).

Step 13. To create a sub-set ITS architecture, a new physical viewpoint is created that includes as much of the functional viewpoint as is required by the sub-set. Several sub-set ITS architectures can be created from one functional viewpoint using the FRAME Selection Tool. It is possible to experiment by selecting different parts of the functional viewpoint - or to create different physical viewpoints for the same selection.

The FRAME Selection Tool produces a set of files that contain tables providing details of the contents of the functional, physical and organisational viewpoints. It is also possible to export the contents of the viewpoints as a separate database for use with tools such as ACCESS.

Due to the flexible nature of the FRAME Architecture, because it is intended to be easily adapted to suit individual ITS implementations, it has not been possible to create an automatic diagram creation feature. But these can be easily created using the tables and a drawing tool such as VISIO.

The following figures illustrate some of the materials that can be produced as a result of creating an ITS architecture from the FRAME Architecture, using the output from the FRAME Selection Tool. They relate to the ITS architecture developed for Kent County Council in the UK and are reproduced by kind permission of that Council.

The diagrams and tables shown below have been created from the tables produced by the FRAME Selection Tool. Using these tables, other diagrams and tables can be created that are important to specifying and visualising the architecture.

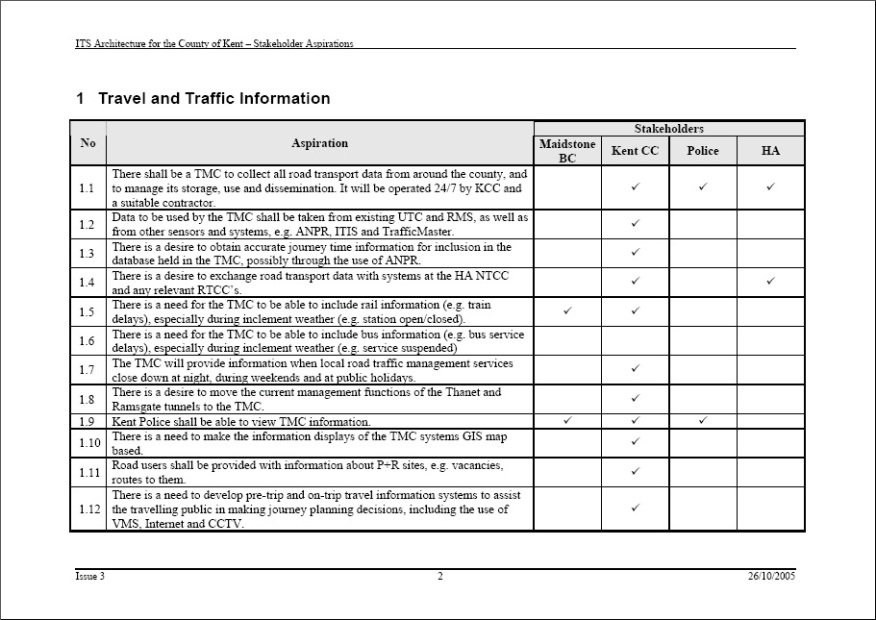

This diagram shows a sample page from the list of service descriptions that were produced from the "stakeholder aspirations" resulting from the stakeholder consultation exercises carried out by Kent County Council (KCC) before the ITS architecture was created.

Figure : Example of service descriptions for the Kent CC ITS Architecture

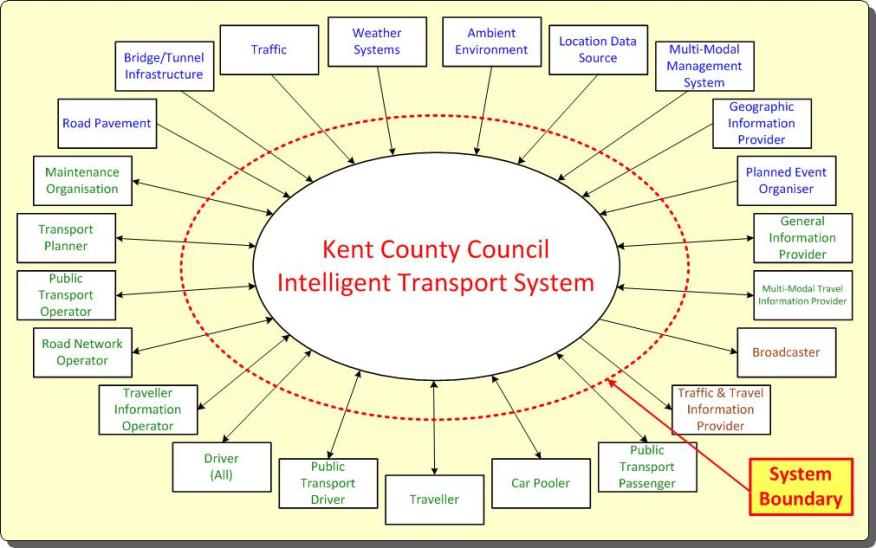

The "context diagram" shows the communications links to all the entities outside the Kent ITS Architecture. The system boundary is shown by the red dashed line. Some of the communications links that cross the system boundary will be electronic, such as link to the Maintenance Organisation, whilst others will be through human machine interfaces (HMI), such as links to "Operators" and Travellers. In the example shown, the term "operator" means a person responsible for managing a computer system. Other communications links will be different again. For example, links to “Traffic” will be through a variety of mechanisms.

Figure : The Kent CC ITS Architecture Context Diagram with the system boundary

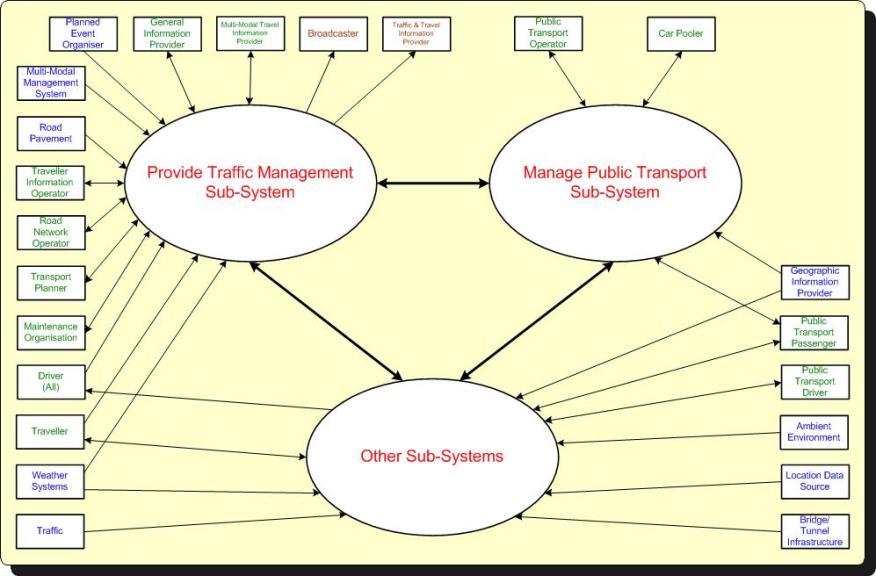

In the example from the Kent ITS Architecture below, all the components have been grouped into three "sub-systems". Other ITS architectures could have more or less of these sub-systems.

Figure : The Kent CC ITS Architecture top level physical viewpoint diagram

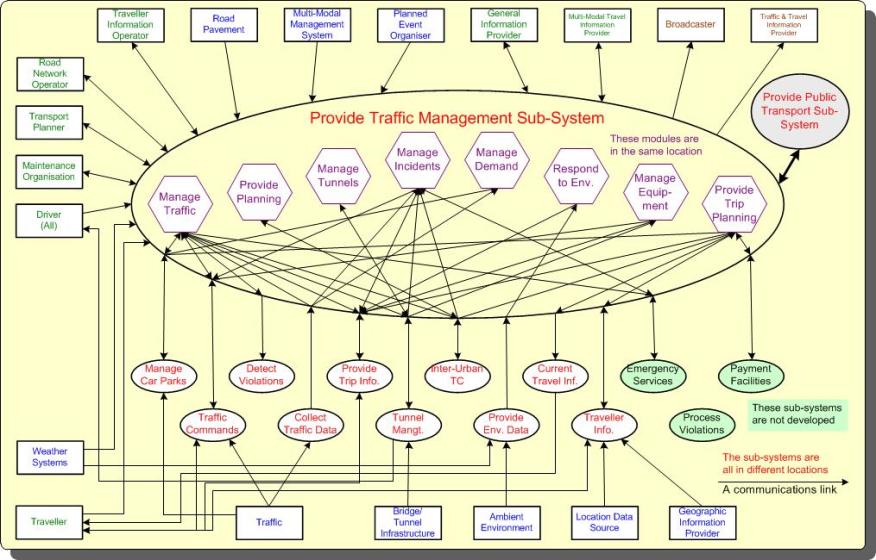

The components within this sub-system have been grouped together to form several "modules", each of which delivers all or part of a service. For each "module" its communications links to the world outside the Kent ITS Architecture are shown and are the same as the links shown in the context diagram. Similar diagrams to this were produced to show the modules in the other two sub-systems.

Figure : A Kent CC ITS Architecture subsystem diagram

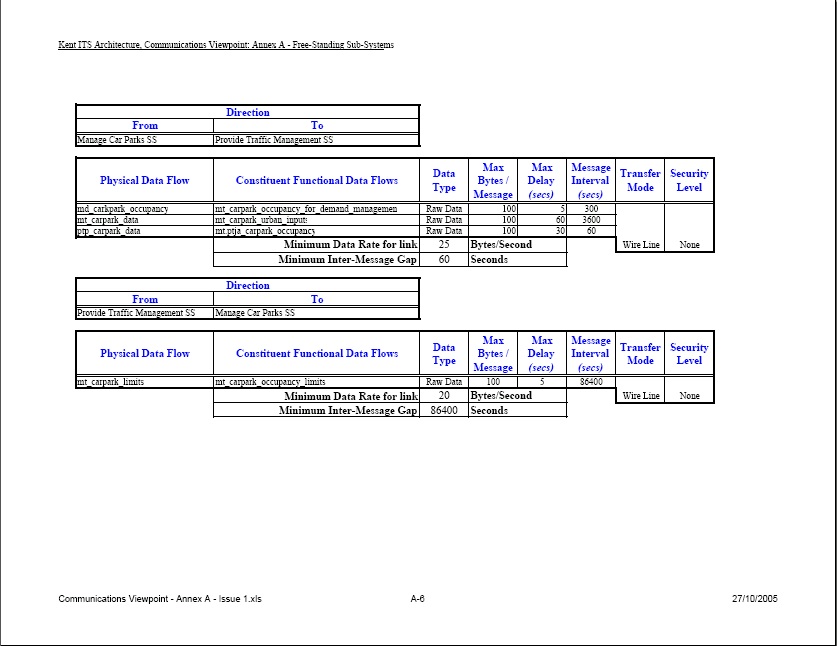

This is part of the table in the communications viewpoint which shows the requirements for some of the communications links identified in the physical viewpoint. In this particular instance, the link is between two modules in different sub-systems. Other similar tables were produced for other electronic links between modules, sub-systems and for the exchange of data with the outside world. The information in these tables would be used to define the types of links required and help specify the standards with which they must conform.

Figure : A page of the Kent CC ITS Architecture communications viewpoint

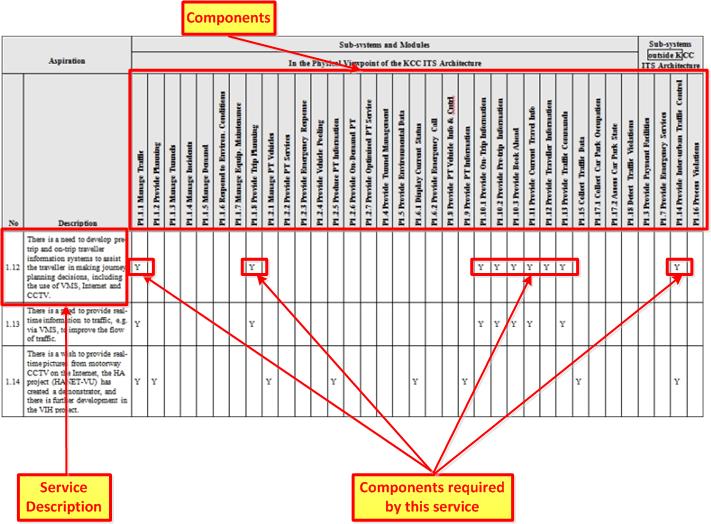

This is part of the table that shows the links between the "aspirations" created by the stakeholders and the "modules" in the physical viewpoint. This table is most useful if the services are to be implemented over a period of time, as it shows which "modules" will be needed by each service. In some instances additional services can be provided "for free" because the components specified in the physical viewpoint have the capability to be shared.

Figure : A page from the Kent CC ITS Architecture table of components required by services

Additional diagrams and tables can be created for other viewpoints that will provide more detailed insights into an ITS architecture (See What is ITS Architecture?). Examples could include:

Free information about using the FRAME Architecture - including extending it - is available from the FRAME Architecture website at: http://www.frame-online.net/. To find some of this information, scroll down the home page to find links for specific topics. The web site’s “FAQ” facility (in the "FRAME ARCHITECTURE" drop down menu) and its pages in the "LIBRARY" drop down menu, for example "Articles and Papers", provide further information. Any questions (and comments) that are not answered by any of these resources can be sent to info@frame-online.net.