When users of ITS have a choice they choose to engage and adopt new technology based on a number of factors:

Users interact with Intelligent Transport Systems (ITS) using senses such as sight, hearing and touch. For example – for an ITS-based Variable Message Sign, to be effective, it has to be visible and the message readable/recognisable.

User engagement with ITS and the various types of services that ITS provides, is of special importance to the suppliers of ITS to Road Network Operators – and to the road users themselves, either indirectly or directly. These include:

The design of the HMI for ITS technology, in terms of how it affects the dialogue with the user (the software for example) is very important to promote ease of use. For an interactive device, important dialogue issues include: length of “timeouts”, language used and menu structure.

The context of use is an important consideration when designing how users interact with ITS. An ITS device should not be described as “useable” or “ergonomic” without also describing the context in which that use takes place.

Users engage with ITS to obtain different services – such as information, warnings or assistance/automation. The human factors issues associated with these different “levels” of interaction are very different and they may have safety implications. Appreciating the key differences and understanding these issues can help the road network operator to purchase, design and implement appropriate ITS.

Road Operators have a duty of care to the users of their road networks. Whilst people are individuals and will make their own decisions, they can be encouraged and enabled through ITS to adopt safe practices in the use of the roads. In terms of ITS information provision, the Road Operator should ensure that the information provided is as clear and correct as possible – and that the ITS provided is safe, well maintained and fit for purpose so that it can be easily used.

Particular attention should be given to safety-critical tasks. The Road Operator may wish to introduce driving restrictions in some contexts where there is a particular risk. Examples might relate to health and safety considerations such as:

The Road Operator has responsibility for the work and conduct of its staff and this will include responsibility for any ITS they may use as part of their jobs. Choice of HMI is a specialist area, and advice from human factors professionals is recommended

The Road Operator should be mindful of human factors when designing or procuring ITS. How ITS services are implemented determines how easily they can be used. This influences user acceptance and adoption – as well as adaptation of behaviour and overall safety.

The introduction of new technology, such as ITS, tends to allow not only more efficient ways of undertaking tasks – but completely new ways of working. For example, the availability of real-time travel information on a personal hand-held device changes information needs – and relationships between the user and the providers of transport services. Information services may also pose challenges of security and privacy when individual data is stored and processed as part of the ITS. (See Legal and Regulatory Issues)

New HMI may lead to the development of national and international laws and vehicle regulations. New technology that has emerged in recent years includes Bluetooth headsets for mobile phones and head-up displays within vehicles.

Automation, especially of road vehicles, is likely to involve institutional issues. There may be some public distrust of automation, particularly around road safety and potential job losses (for example, automated truck platoons may require fewer drivers). Automated driving may require the development of national and international laws and vehicle regulations. (See Automated Highways)

Humans can interact with the outside world, including ITS, in myriad ways and there is a wide variety of technology available to assist this interaction. The most common HMI components used are described here. HMI elements – good, poor and indifferent – are invariably present in computer systems and ITS. For example:

Public displays may also incorporate important HMI features – such as:

It is a commonly-held ‘truth’ that people have five basic senses:

In fact people have others senses as well, including: vestibular (balance and movement), kinaesthetic (relative position of parts of the body), pain, a sense of temperature and a sense of time passing. All these allow people to interpret the world around them, at different levels.

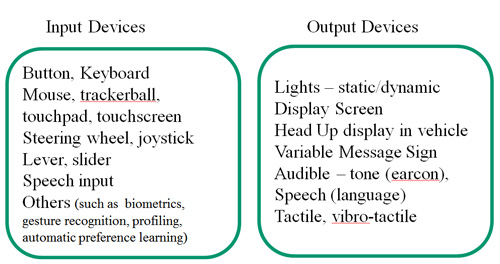

There is a wide range of human machine interface components to support the interaction between road users and ITS.

Engagement with ITS – HMI components

Use of hardware (such as buttons and a display screen) allow road users to interact and to develop a dialogue with the ITS technology. The extent to which the dialogue is efficient and effective (and liked by the user) depends both on the detailed design and performance of the interface hardware and also the design structure of the dialogue.

The designer of the HMI has a very wide range of choices. For example, in hardware design, buttons can be “latching” (they maintain their state after being activated) or “non-latching” (momentary) with different sizes, shapes and clearances to other buttons, different levels of resistance and sensitivity. The hardware design may also take account of implicit associations and knowledge of users (such as a familiar shape or icon and colour – such as red for danger).

The design of the dialogue (its structure and management) is also very important to promote ease of use. Important issues include: length of “timeouts”, language used and menu structure.

Although the design of the HMI of vehicles is the domain of the automotive manufacturer, in-vehicle HMI is often supplemented by drivers with the addition of mobile communications and information systems. These may or may not be designed for use while driving and their use can have a significant effect on drivers.

Choice of HMI is a specialist area, and advice from human factors professionals is recommended. The HMI should be based on:

There may be a trade-off between ease of learning and ease of use.

Try it with new users – what is their experience? (See Piloting, Feedback and Monitoring)

To be effective, all transport signs need to be noticed, understood and followed. Much has been studied and written about the human factors of road signage. Signage should be considered as part of an overall information provision strategy for road users. There will also be human factors considerations in its construction, installation and maintenance.

Variable Message Signs (VMS) are a typical form of ITS, particularly used on interurban roads to convey messages to drivers. Key considerations for VMS include:

Design of vehicles including their HMI is the domain of vehicle manufacturers who consider the “look and feel” of their vehicle’s HMI as part of their brand image.

Information and communication systems may be factory-fitted, fitted as an aftermarket option or (more commonly) brought into the vehicle by the driver. Examples include SatNav guidance systems and fee collection transponders. Some countries have legislation restricting the use of specific devices such as hand-held mobile phones. The HMI of in-vehicle devices may or may not be suitable for use while driving and road operators should be aware that use of such “secondary” interfaces by drivers may contribute to inattention and distraction.

Some Road Operators and other information brokers have sought to use data provided by large numbers of transport users to help road performance. This is called “crowdsourcing” which uses location and communication information from smart devices. The engagement of users may be implicit as a result of their use of other services, or may require more explicit participation. Increased engagement and richer data may be sought by offering interaction and competition (“gamification” – turning it into a game) or by using user-derived content from social media. There are privacy issues to consider, but road users may be willing to engage in services that offer benefits to them, such as ride sharing.

The context of use describes the conditions and environment in which users interact with ITS. Examples include:

The context describes the main issues likely to have a bearing on the interaction such as “who” “when” “where” and the environmental conditions.

The context of use is an important consideration when designing how users interact with ITS. It can affect motivation, performance, attitudes and behaviour of the users and the overall efficiency and effectiveness of the interaction. An ITS device should not be described as “usable” or “ergonomic” without also describing the context in which that use takes place.

Any measurements of usability (user-friendliness) should be carried out in an appropriate context and include a detailed description of that context.

Part of the context of use includes the user(s) themselves – who can be characterised in many ways including their knowledge, skills, experience, education, training, physical attributes, motor and sensory capabilities. The user’s experience is the context of events that have immediately preceded this interaction with ITS. (See Diversity of ITS Users)

The user can also be identified in terms of their current mood, time pressure and their goals in interacting with the ITS.

Tasks are the activities undertaken to achieve a goal and are part of the context. Issues here include the frequency and duration of the tasks to be undertaken. (See Human Tasks and Errors)

The technological environment includes the software and hardware of ITS. For example, interacting on a small mobile screen or a full screen are different contexts. The speed of processing and the characteristics of a keyboard can all affect the usability of ITS. The availability of reference material/user guides and other equipment may also be relevant.

For some interactions with ITS, the organisational context may be relevant such as the attitudes of an organisation’s management and employees towards the ITS, the way task performance is monitored and any internal procedures or practices. The structure of the organisation, reporting and reward arrangements, the availability of assistance, and frequency of interruption – are all relevant factors.

Interaction with ITS can be different depending on whether it is an individual or group activity, and whether it is undertaken in public or private. For example, use of an individual ticket machine may involve some social pressure to complete the interaction quickly if there are others waiting to use the facility. Driving is a kind of social activity where there may be both cooperation and competition.

This includes a number of environmental issues:

Another way of representing the various contextual factors is the 5W+H checklist:

Always investigate and document the context of use when designing how users interact with Intelligent Transport Systems as ITS need to be designed for specific contexts.

The following five steps are recommended in specifying the context of use for an ITS (product or service):

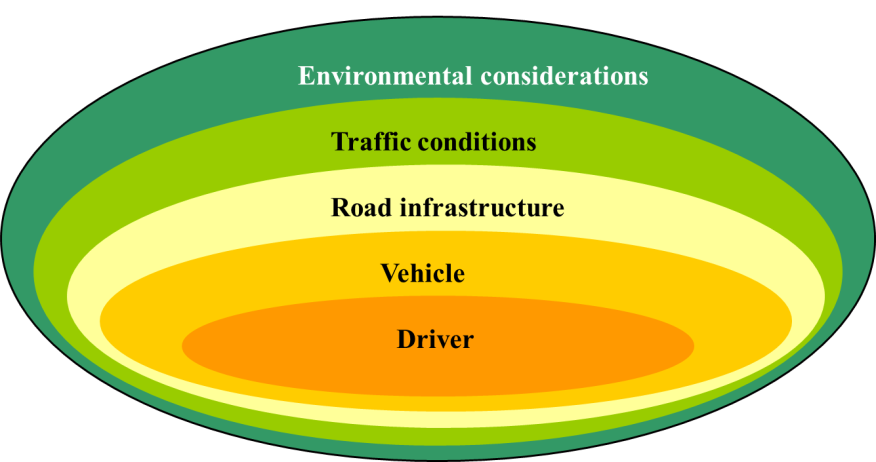

Checklists can be helpful in describing the context of use. Diagrams can also be helpful. The example in the figure below concerns a driver’s use of an in-vehicle ITS.

Context of ITS use within a vehicle by a driver

Develop an evaluation plan for the ITS (system or service) and then undertake trials in realistic contexts. Based on feedback and results, re-design the system or service or modify the context of use to achieve the required level of usability.

In the longer term, the Road Operator should set up mechanisms for monitoring ITS use and receiving feedback from users. (See Measuring Performance and Evaluation)

Particular attention should be given to safety-critical tasks. The Road Operator may wish to consider imposing restrictions on interactions in some contexts of use where there is particular risk. Examples might relate to health and safety considerations such as:

ITS can support users with information and warnings, and can provide various levels of assistance and automation depending on the service.

The human factors issues associated with these different “levels” of interaction are very different and these may have safety implications. Appreciating the key differences and understanding these issues can help the Road Operator to purchase, design and implement appropriate ITS.

The manner in which ITS services are implemented impacts on their ease of use. This greatly affects user acceptance and the degree of behaviour adaptation, as well as overall safety.

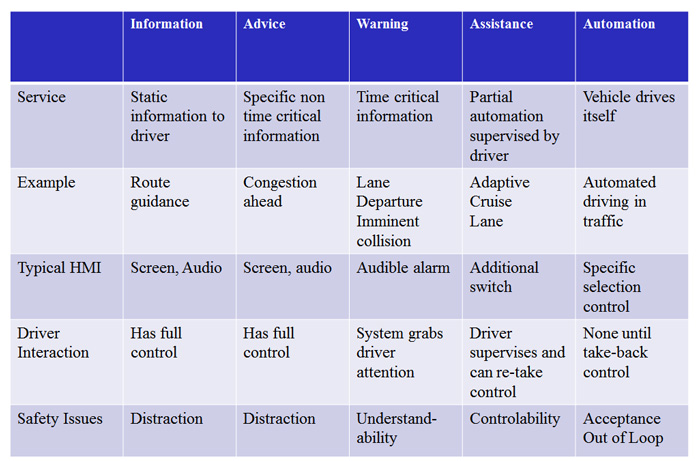

One characteristic of ITS is the level of support provided to the user. Using a five-fold classification, example ITS services are shown here:

There are different levels of automation for road vehicles:

The human factors and safety issues are different for each different level of interaction or level of automation. The design of the HMI must be different for the different levels – in order to best support the user and promote safety in the transport environment.

The figure below provides a summary of the levels of support and HMI implications in the context of vehicles and driving. For further information see Driver Support

Levels of ITS support to the driver

It is important to identify the level of support that ITS is providing to users. Task and error analysis may be useful. (See Human Tasks and Errors)

Secondly, it should be appreciated that the human factors and safety issues are different for each different level of support – so the design of the human machine interaction (HMI) must be different for the different levels, to best support the user and promote safety in the transport environment. (See Road Safety)

Road users can access information in a variety of forms and via different sources. Particular safety issues arise when users, such as drivers and road workers are also involved in safety-critical tasks such as driving or operating machinery. Here, distraction can be a problem so information has to be designed and delivered so that it can be easily used – in the specific context of use. Human factors guidelines are available to assist. Road Operators may wish to restrict access to distracting sources of information to improve safety or design procedures so that information can be accessed safely.

Advice is more specific information that implies or suggests a particular course of action, such as suggesting an alternate route in times of congestion. Understanding and comprehension of the advice is a key issue. The information supplier should provide advice in a clear way which is likely to be easily understood by the intended users. The user response should not be assumed – but should be observed.

Warnings are specific pieces of advice that may require action to be taken in a time-critical way (within a few seconds). Road users have a short period of time in which to understand the warning and take appropriate action. Suppliers of warnings – such as the operations staff at a Traffic Control Centre – should carefully design and test them (to ensure they are well understood and create the intended response) and should consider practice and training so that users become familiar with how to respond. The user response should not be assumed – but should be observed.

Assistance systems automate part of a road user’s task under their own supervision. Driving assistance systems which partly automate the driving task are becoming more common. Specialist machinery used in road construction and maintenance is also becoming more automated. The line between assistance and automation is not completely clear.

Whilst assistance and automation can provide operational and safety benefits, there are several potential safety issues that need to be considered. A key issue is that users over-trust the assistance/automated system and may not appreciate its operational limits. Training and experience should assist here. A related potential problem is poor supervision of the ITS service delivery. (See Automation and Human Factors) It may also be that users become de-skilled as a result of reliance on the assistance – and so are not well prepared to take back control if necessary. Training and practice are good ways to mitigate problems.

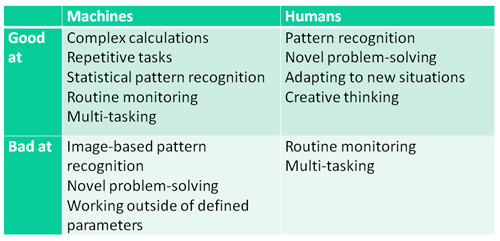

In the modern world, many processes are automated by machines. Whereas people would previously have been responsible for completing each individual process, the role of the person is typically now limited more to monitoring the machines that undertake those processes. The idea is that machines are employed to do the simple, repetitive tasks at great speed – and a person is on hand to sort out any problems that might occur. In theory this plays to the strengths of both machines and people. The (so called) “irony of automation” is that the human takes on the role of system monitor – and that this role is far from suitable for human attributes.

People and machines are good and bad at different tasks and roles. The figure below highlights some of the key distinctions:

Roles Suited to Humans and Machines

In ITS the role of automation is often to remove from the user responsibility for tasks that people generally find difficult or mundane – so they can concentrate better on tasks which either cannot be automated or cannot be automated efficiently and effectively.

It may not always be easy to make a clear distinction in the appropriate division of labour. It may be that a system can only automate parts of a task, or that there is an output from an automated task that must be fed back to the user at some point. Issues can arise if the division of labour is such that a user is required to perform a function for which they are not suited, as a direct result of that division.

Even if people are given roles suited to their skillsets, and tasks are suitably reallocated for automation so that the user is able to only consider the critical tasks – performance may be compromised if the user is so far removed from the task (“out of the loop”) that they are unable to intervene effectively when required.

People perform poorly when overloaded, but performance also drops off when under-loaded as it can cause the user to switch off mentally. It may be that any corresponding loss of attention means an operator fails to spot an important development within the system. Even if operators are alerted to an important development by an alarm – their understanding of what needs doing to rectify the issue may be impaired if they have not been kept sufficiently in-the-loop to maintain their situational awareness. This awareness is essentially the user’s understanding of: what is happening within the system, what will happen next and what the implications are. Loss of situational awareness could arise through poor task allocation within the system, as a result of cognitive under-load or through the user placing too much trust in the system to perform as expected.

If a situation requiring action by the driver arises, automation may mean that the system warns that an intervention is necessary – even if the user is sufficiently alert and knows what to do. If the alert is not given early enough, the operator may be unable to act, despite knowing what to do in principle.

Automation can have negative consequences and designers will need to consider the possible implications of automation before introducing it into any design. Correct use of automation can prove extremely useful to the operator and to overall system performance. Transport systems and networks are often highly complex and ITS offers the potential to use technology to simplify aspects of these systems from the perspective of the user. Automation can be a useful means of reducing the overall complexity of the system so that individuals are able to focus more clearly on the most important processes. The key requirements in order to be able to do this effectively and safely are effective task allocation and the avoidance of overload or under-load.

Ideally, designers should seek to obey the following principles:

To avoid overload/underload, designers should also take account of the following principles: