Understanding who uses ITS and how it influences their behaviour provides a wealth of information which can be harnessed to improve the design, implementation and operation of ITS applications. Users are human and humans make mistakes! Some are quickly realised and may be corrected. There are also errors that may have wider consequences and safety implications.

Everyone is different. Some differences between people are innate and last a lifetime, some may come and go, and some may develop slowly over time. It is well known that physical characteristics such as strength and reaction time vary between individuals – but human behaviour in engaging with increasingly technological transport systems also depends on an individual’s information processing capacity. How users perform in their interaction with ITS will vary considerably. An individual’s performance will also vary over time depending on a complex interplay of factors.

Interaction between users is also an important issue. “User Groups” may help to distinguish users of ITS who have certain characteristics or factors in common – but still include a diverse range of individuals. An analysis of how individuals behave when interacting with other individuals, and how they behave as a group, provides useful insights which can help shape the policies adopted for Road Network Operations.

Stakeholders in the successful implementation of ITS-based systems and services include the Road Operators (ROs), their providers of technology and related services, and national and local government. The users themselves can be categorised in a number of ways – a basic one being:

These stakeholders, although not completely distinct, can be further disaggregated. Drivers, for example, can be categorised in many ways, according to:

Vulnerable Road Users (VRU) (See Road Safety) may include:

Road operator employees will include:

National and regional road authorities and those responsible for operations – the Road Operators – have a duty of care to the users of their road networks. Whilst people are individuals and will make their own decisions, they can be encouraged and enabled to adopt safe practices in the use of the roads. By taking account of human motivation and decision making, Road Operators are better placed to understand how people behave both individually and in groups – and how best to influence that behaviour in order to manage the road network.

In terms of ITS, the Road Operator should ensure that the information provided is as clear and correct as possible, and that the ITS provided is safe, well maintained and fit for purpose – so that it can be easily used.

The Road Operator is responsible for the work and conduct of their staff and this includes responsibility for any ITS they may use as part of their jobs.

The Road Operator needs to understand the tasks to be performed by its workers – and to appreciate the scope and consequences of user errors and how these can be avoided or their consequences mitigated

The Road Operator should consider the role of education and training for its workers. Education allows individuals to form mental models of why and how things work and may improve performance by reducing errors and increasing motivation. Performance generally benefits from training although “overtraining” and complacency/boredom may become a negative factor in some cases

Many countries have legislation concerning how disadvantaged users or those with special needs should be taken into account. Consideration has to be given to design of ITS for all types of users given the importance of creating an open and useable road transport system for all. Road Operators should ensure that ITS is designed to accommodate the full range of users wherever possible. If not, an assessment needs to be made about how those not provided for will be affected and whether the consequences are acceptable. If not, an entirely different solution may be needed.

These “design for all” considerations may conflict with economic or operational efficiencies. Depending on ownership and governance structures, the Road Operator may be subject to purchasing constraints (for example having to use a particular supplier) and this may limit the design choices for ITS.

As an employer of, for example, control room staff and road workers, a Road Operator will probably have statutory duties towards their workers in areas such as health and safety practices and the safe use of ITS.

ITS can provide much helpful information and assistance to drivers and other road users. It can also pose potential problems. Diverting attention to in-vehicle information and communication systems can detract from driving performance and decision making. This has led to some countries enacting protective legislation such as banning the use of hand-held mobile phones and texting whilst driving. The Road Operator may need to take account of this in the ITS systems provided to their workers and in their operating practices. They may also be made responsible for enforcing national laws on its roads.

The HMI principles described here are designed for Road Operators to apply in all countries. However, the application in developing economies may need to be tailored to the specific context. Some specific points to take in to consideration are provided below.

Developing economies may have a greater diversity of users, particularly in terms of educational provision. For example, the literacy level or level of familiarity with technology cannot be assumed to be the same as in developed economies and multiple languages may need to be taken into account.

The road environment and the balance of user groups varies considerably from country to country – for example, there may be a greater amount of animal transport, pedestrians and cyclists (vulnerable road users) and fewer drivers of motor vehicles. The mix of vehicles driven or ridden transport may be very different from that typically used in a developed economy, often with a greater proportion of powered two-wheelers (PTWs). Similarly, the infrastructure – for example, traffic control, may be less developed, particularly in rural areas.

Countries have different laws, but developing economies may be less advanced in terms of safety requirements and enforcement (for example concerning traffic offences and the use of mobile phones while driving). With different social and cultural background, the norms of behaviour by road users and their attitudes towards the rules of the road may deviate widely from safe practice. The extent to which economic forces and peer pressure drives behaviour may need special attention in modelling user behaviour.

The degree of investment in ITS technology and services, its reliability and that of its powered energy and communications may be more variable than in developed economies. Lack of reliability is likely to affect deployment of ITS and the behaviour of users. Developing economies may not have access to trained human factors professionals to advise Road Operators in aspects of user behaviour. (See Building ITS Capacity)

Designing an ITS product, system or service for the people who will use it is not simply a case of designing to a required specification for a ‘standard’ person, as there is no such thing as a standard person – everyone is different. Whilst people possess certain qualities and limitations that apply, at least in part, to everyone, they are by no means universal. For example, it is possible to quantify reasonable upper limits for human visual performance – but some people cannot see anything at all, others may have blurred vision, and for those who see in sharp detail there may still be issues such as colour blindness affecting their vision. Some differences between people are innate and last a lifetime, some may come and go, whereas some may develop slowly over time. Whatever the reason, differences between individuals must be accounted for in any design, and this includes ITS.

Whilst human variability is vast in scale, there are certain key areas that are likely to influence ITS practitioners in their work.

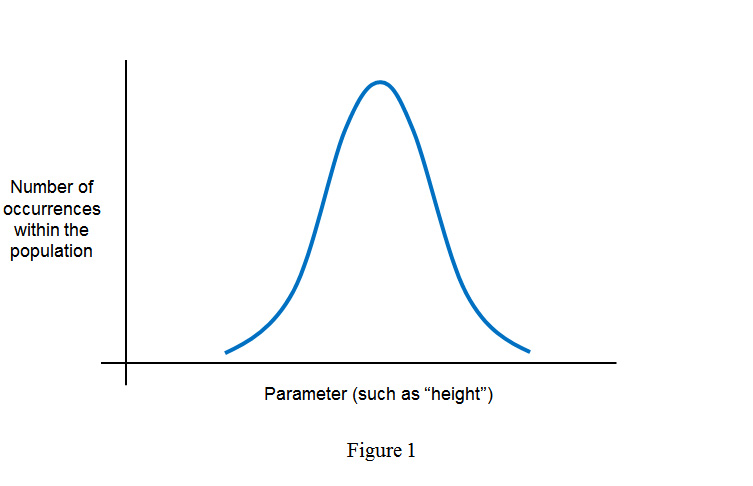

The vast majority of quantifiable human attributes (especially physical characteristics) follow what is known as the ‘normal’ distribution. This is a distribution seen throughout nature and is represented in the figure below. It shows that the average value within a population (for a criteria such as height) will be the most common, with more extreme (large or small) values being progressively less common. There is no such thing as an average person as there is almost certainly nobody alive that is exactly average in every conceivable parameter. Instead the population is comprised of individuals who may be higher up the distribution on some parameters and lower down the distribution on others.

Natural variability in the population

It is unavoidable that as people age their senses and faculties start to deteriorate. Eyesight and hearing are amongst the most prominent in terms of the senses, but mobility will also usually be affected – and at some point most people will begin to experience a slowdown in their speed of mental processing. The ability to learn new skills quickly will also reduce over time. The converse of this is that the faculties of younger road users may still be developing. Basic senses in younger people may be well functioning, but cognitive abilities may not yet be at adult levels, which can impair decision-making. Younger users will also typically be smaller and less physically developed than adults.

Differences based on social and cultural background can sometimes be pronounced – and although generally harder to quantify than age-related decline, their impacts can be predicted at some level. Key considerations in ITS will relate to factors such as attitudes towards different road users, acceptance of technology and driving conventions. For example, cyclists and car drivers often experience confrontation based on different perceptions of each other. General attitudes of different user groups can often be determined by engaging with relevant users, to understand and help predict and take account of potential conflicts – whether they be within user groups, between user groups, or between users and technology.

Four high-level principles help guide those working with ITS:

If someone was to design a door it would clearly be foolish to use an average person’s height to determine the door height – since it would not be usable by at least half of potential users. Instead the door should be designed to accommodate the tallest users as there are no detrimental effects for shorter users. In the same way, when designing an overhead gantry-mounted variable message (VMS) information screen, the text should not be at a font readable only by those with 20:20 (average) vision. By making the text larger, a greater proportion of road users are taken into account and the text is easier to read by all.

There may be times when it is not possible to accommodate everyone at the same time. In such cases, the principle of designing for the 5th-95th percentiles of the population is generally adopted. If, for example, someone was designing a forward/back seat adjustment mechanism for a car – a key parameter will be the leg-length of users. If all users were ranked according to leg length:

Adopting the 5th– 95th percentile principle means that the seat is made adjustable so as to be used comfortably by the middle 90% of users in terms of leg-length. If it is possible to design a seat that is practical and can accommodate the 1st– 99th percentiles, this would be even better.

Given the importance of creating an open and useable road transport system for all, traffic planners, engineers and designers should seek to accommodate the full range of users wherever possible. If not, consideration must be given to how those whose needs have not been taken into account will be affected – and whether these consequential effects are acceptable. An entirely different solution may be needed.

If the principles outlined above are applied and an effective design is established for one application, it may not be the case that this can simply be transferred to other applications. An example could be a system that has been implemented successfully in one country and is being considered for use in another country. Cultural differences between users or technical differences in the transport infrastructure may mean that users interact with the system in a different way – and that there are unintended effects that had not previously been identified in the original application. Variability may also be an issue where a system is already established. Changes in user populations can happen over time and changing external factors may alter the overall operation of the system. Whenever updating or introducing a new system, it is useful to conduct user testing.

The following universal aspects of human variability should always be taken into account in the design and operation of any facility or service that will affect road transport systems:

Human performance describes how easily and efficiently an individual achieves a certain outcome – such as navigating to an address, crossing the road or buying a bus ticket.

Human performance is based on a physical and cognitive (mental) control “system” that is the result of millions of years of evolution. Human action is largely effective and adaptive even when carrying out complex tasks – but humans are not machines – whatever role they are undertaking. It is important to understand the limits and the variability of human performance so that transport systems and ITS can be designed and operated accordingly. Performance varies between people and an individual’s performance also varies depending on a complex interplay of factors. These variations can make or break the success of new applications of ITS, such as cooperative driving. (See Coordinated Vehicle-Highway Systems)

People make errors! Sometimes it is useful to draw a distinction between “slips”, “lapses” and “mistakes”. Slips and lapses are skill-based errors. Slips occur when there is a mismatch between someone’s intention and action – intending to do the thing but doing it incorrectly. These are often quickly realised and may be corrected. Lapses are when a user forgets to do something or their mind goes blank during a task. Mistakes, on the other hand, result from some misperception or misjudgement and are decision-making errors – doing the wrong thing but believing it to be . These are often much harder for a user to identify and correct. We cannot predict exactly when errors will occur but there has been considerable research concerning their context and likelihood.

Performance is affected by specific impairments that people may have – these can be (semi-) permanent, such as a broken arm or colour-blindness or temporary. Examples of temporary impairment include tiredness – which is a particular issue for shift workers. Individuals can also be intoxicated or unwell which can affect their performance.

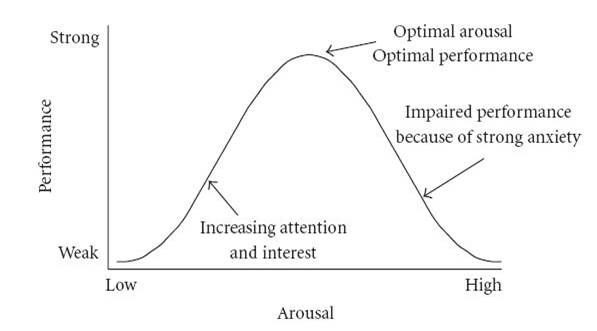

Human performance varies depending on arousal (excitation level). Individuals can be under-aroused (sleepy, dis-engaged) or over-aroused (excitable, anxious). Individuals perform at their best when at neither extreme.

Arousal/Performance curve

Performance often depends on motivation (See Motivation and Decision Making), which can also interact with arousal. Individuals tend to perform better when they are well-motivated.

A control room operator using a terminal, or a public transport user reading dynamic signage, may concentrate on the terminal or the sign as a single focus of attention. This contrasts, for example, with a driver observing the road whilst simultaneously adjusting the car entertainment system. Sharing of attention between two tasks is known as the “dual task paradigm”. Performance when undertaking a single (or primary) task is usually better than when trying to undertake another (secondary) task at the same time – because mental resources have to be shared between the tasks.

It is well known that performance varies between individuals. Issues such as strength, reach, endurance and reaction time are examples of physical ergonomics which can be measured for different groups.

Human performance in the context of today’s increasingly technological transport systems also depends on an individual’s information processing capacity. To a large extent this is affected by how an individual’s various physical senses or “channels” – such as visual and auditory – handle the streams of information encountered. All channels require mental resources to process information and these channels can become overloaded. There is more interference within channels than across them. For example, talking whilst engaged in a control task is easier than operating two controls or holding two conversations simultaneously.

Research suggests that not all mental resources are equal and “multiple resource theory” accounts for how it is sometimes possible to do two things at once – as long as specific limited mental resources are not required for both tasks.

Training can greatly affect performance through repetition, practice and familiarity. For example, a public transport user familiar with a ticket machine can make a purchase more quickly than an unfamiliar traveller. Some activities, such as the use of the clutch when driving, can become almost unconscious requiring very little effort. Performance generally increases with training although “overtraining” and complacency/boredom can become a negative factor in some cases.

Education allows individuals to form mental models of why and how things work and may therefore increase performance by reducing errors and increasing motivation.

Expect and allow for variability between people and for a variation in one person’s performance/ability at different times and in different circumstances. The variability may be obvious (such as age, size, physical disability) or may not be. Where possible, design for the least able and most endangered. (See Diversity of and user groups)

People make mistakes, so it is essential that ITS is designed so that systems and processes minimise the possibility of errors and provide opportunities to recover from them. (See Automation and Human Factors). Task and error analysis may be helpful. (See Human Tasks and Errors). Particular care needs to be taken when an individual’s mistake could have safety consequences for themselves or other road users.

Driving – and Powered Two-Wheeler (PTW) riding – is a complex and safety-critical task which requires physical and mental resources. Driving skill and performance can be improved through education and training. A minimum level of performance should be required at all times whilst driving. Drivers’ skills need to be tested, at least initially, and a minimum standard should be enforced. New technology can introduce tasks additional to driving, such as making a phone call – which can impair driving performance and should be discouraged on grounds of road safety.

Vulnerable road users – such as cyclists and pedestrians of all ages – will vary, for example, in the degree of their physical movement, direction-finding and road awareness. All information and directions aimed at them should be designed to be simple, unambiguous and easily perceived.

ITS infrastructure (including signs, payment facilities, speed limits) should be designed to take account of the intended user population and the variations in performance that they have. Many human factors standards and guidelines are available which are suited to different ITS applications. (See HMI Standards and Guidelines). Using internationally agreed standards and guidelines for HMI is recommended – they help to promote familiarity and often provide multiple signals to the brain for recognition (for example, use of colour and shape).

When possible, new designs should be simulated and trialled with the intended user population to ensure that human performance shows that they can be easily understood and used. (See UK Smart Motorways )

ITS infrastructure should also be designed to take account of the performance limitations of those personnel involved in their maintenance. (See Work Zones)

Public transport operators need to be mindful of the broad range of human performance and specific disabilities that may impair performance – when designing or purchasing systems such as display screens and ticketing facilities to: (See Diversity of Users)

The Road Operator will need to set standards, provide training and undertake regular performance reviews of control room operators. (See Traffic Control Centres) They need to:

Human factors professionals can assist in designing work and shift patterns to minimise performance degradation. (See Infrastructure)

The road should be considered a potentially hazardous working environment for personnel such as maintenance and emergency response workers. Road Operators should:

Human factors professionals can assist in designing work and shift patterns to minimise performance degradation.

The “user friendliness” of the road network depends on a complex interaction between the technical systems – such as traveller information, route guidance and traffic control – and the road network users. Ultimately, people are individuals and will make their own decisions, but there are many theories and models that can help us to understand individual motivation and the effect this has on behaviour.

By taking account of human motivation and decision making, Road Network Operators should be better placed to understand how people behave both individually and in groups – and how best to influence that behaviour in order to manage the road network.

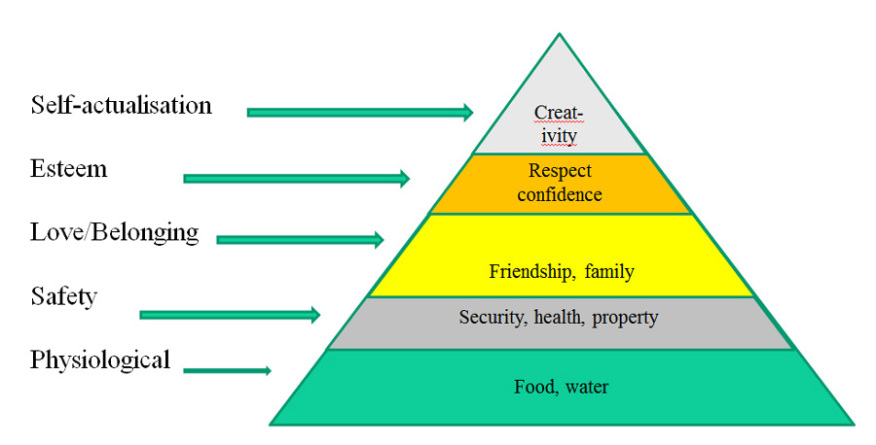

The psychologist, Maslow proposed that humans have needs that influence their behaviour, which can be arranged in a hierarchy. Once a need is satisfied, then behaviour is influence by the next (unsatisfied) need in the hierarchy. The most basic are physiological needs (such as food and sleep). Once these are satisfied, safety needs take over and so on.

Hierarchy of Needs

Expectancy theory says that choice or behaviour is motivated by the desirability of outcomes. In general people prefer to avoid negative consequences more than increase positive consequences – for example, to arrive at 08.45am for a 9.00am appointment is of minimal benefit but arriving late may be of considerable dis-benefit.

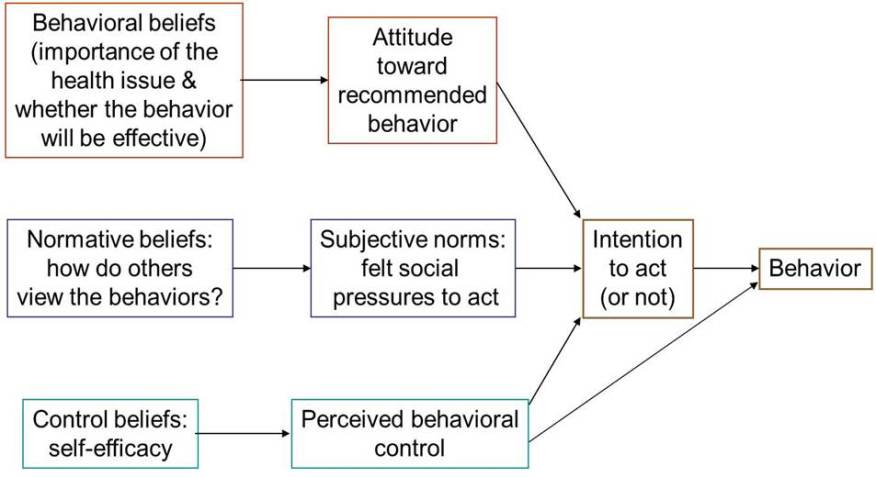

According to the theory of planned behaviour, an intention to behave in a certain way is influenced by three things: the expected outcome (positive or negative), how others will perceive the behaviour and a judgement about one’s capability to carry out the behaviour. It seems that there are “boundaries” within which people feel they can and should act and areas where they feel they cannot. In part, this depends on having “permission” to act in a certain way – whether this is permission one gives oneself or whether it is permission granted by others. For example peer pressure can have a profound effect on young male drivers’ behaviour and their willingness to comply with traffic laws.

Planned behaviour

Incentives and positive reinforcement make a behaviour more likely in the future. Benefits that appear certain and immediate are generally preferred to those that are less certain and more distant. This is called the saliency of benefit.

People have an innate drive to be self-determined – they mostly prefer to be in control and will seek information in order to make decisions. This can be used to advantage in Road Network Operations by providing advice to road users and other travellers. Their trust in information (its credibility to them) depends on many factors including:

In general, people have a poor appreciation of risk (consequences and probabilities), and especially of very small risks. Events that can be more easily brought to mind or imagined are judged to be more likely than events that cannot easily be imagined. This is called the availability bias. Press reports, for example, tend to favour Bad News stories, which promote negative expectations. The managers of Traffic Control Centre operations will be acutely aware of this.

People do not always make choices that are in their best long-term interest. Sometimes “wants” are satisfied before “needs”. So, people are not always economically rational even when all necessary and consistent information is presented. The road users’ response to information messages may differ from what is intended by the Road Operator.

Few individuals constantly seek new experiences. For most there is a tendency to keep doing things in the same way. This is called inertia (an analogy to mechanics). So, people either do not undertake some new activity or continue to do the activity in the same way. To a large extent, these habits are a coping mechanism for the plethora of choices in everyday life.

Decision making also depends on the user’s willingness to seek out all required information (if it is even available). So, a typical approach in many situations is “satisficing” - seeking solutions that are not necessarily optimal but are “good enough”.

One theory proposes that people aim to reduce dissonance (degree of discomfort) between their view of the world and their actions. This can lead to “post-hoc” (after the event) justification of a decision made.

Related to this is a tendency for people to display confirmation bias – a tendency to seek out information (and to preferentially trust that information) that confirms an existing belief, rather than new evidence that may contradict that belief.

In the driving context, Intelligent Transport Systems (ITS) can provide information and assistance to drivers and can play a part in their decision making. Research has led to various models – one model describes driving decisions at three levels:

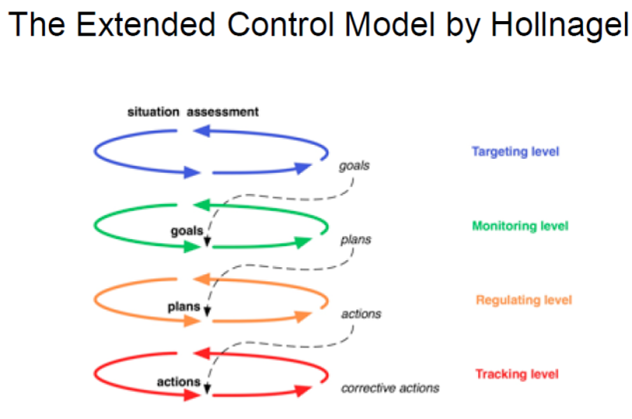

An extension to this model considers driving decisions at four levels with feedback and interaction between them.

The Extended Control Model (reproduced with permission from http://erikhollnagel.com/ideas/ecom.html)

Individual drivers exhibit a range of driving behaviour and styles of driving. Driving can also be considered as a social activity. Interactions between vehicles and between vehicles and other road users are largely interactions between people. An aggressive driving style, particularly in a cooperative driving culture, may be highly offensive. The term “road rage” has been coined to describe extreme feelings or behaviours aggravated by, for example, other road users’ behaviour or driving situations such as congestion.

ITS can provide much helpful information and assistance to drivers. It can also introduce potential problems. Attention to in-vehicle information and communication systems can detract from driving performance and decision making. Although ITS can provide assistance to reduce the drivers’ workload, it is known from research that a sustained low workload (underload) can lead to boredom, loss of situation awareness and reduced alertness. It has been observed that the greater the number of support-system functions which have become available through ITS, the higher the risk of drivers losing competence, which can sometimes be combined with their reliance on ITS functionalities. (See Driver Support)

Road users typically believe they have an implicit contract with the road network operator. This (in their mind) might include keeping the traffic flowing, maintaining the cycleway, and providing safe and adequate public transport. As a minimum, road users’ basic needs should be considered – such as food and toilet facilities and rest stops for longer journeys.

Anger and frustration can arise if the service quality falls below road users’ expectations. ITS can help to manage expectation – for example by providing information about service quality and frequency. This information needs to be available to road users before their journey (for example on the internet, or printed information), and during their journey (for example on signs, notices, mobile devices). ITS, and communication channels more generally, might also be employed to counteract “Bad Press” stories about the road network.

Road users develop habitual behaviours, partly to reduce overload and anxiety about unknown situations. This “learned behaviour” leads to an expectation of permanence and consistency – so if something changes there can be surprise, anger and frustration. ITS, if well designed, can be very helpful in reducing these negative emotions and provide information likely to influence behaviour. (See Traveller Services)

Road closures and changes to schedules should be made available through both ITS and conventional means well in advance, if possible, using multiple information delivery mechanisms.

ITS is particularly useful for providing real-time information about maintenance activities and disruptions to service levels such as traffic congestion. Road users can become anxious and frustrated if they do not have any scope to affect their situation – or if no information is provided (such as the reason for the delay, how long it will be, and what the alternatives are).

ITS information can provide additional confirmation of the situation, sufficient to nudge behavioural change. It should be presented in a clear and authoritative manner. The information should be consistent with other information (unless it is newer and better than existing information).

Apart from a sole road user on an open road, most road use occurs in the context of other road users and so can be considered as a group activity. Social psychology and game theory, involving cooperation and competition, provide useful insights which may be of value to the road operator:

It is noticeable that there are different driving styles in different countries (for example, more or less-aggressive driving, queuing practice and turn-taking, use of mobile phones). Again, ITS can be used to rapidly contain situations or reinforce positive behaviour so that it becomes normalised.