Intelligent Transport Systems (ITS) can support road users in various ways, with information and warnings, and various levels of assistance and automation, depending on the service. Road users interact both with ITS and the wider transport system in complex and sometimes unpredictable ways. There is a need to understand fully the broader context, its dynamic characteristics and the role and responsibilities of its different stakeholders. It is only then that best results from any intervention will be obtained – with a high probability of user acceptance and adoption.

Human factors is the branch of science and technology that includes what is known and what is conjectured about human behaviour and biological characteristics. It can be applied to the specification and design of products and services – and their evaluation, operation and maintenance.

ITS technologies provide users with an interface – known as the Human Machine Interface or HMI. “Behind” the interface is the logic and software of the interaction which contributes greatly to its “look and feel”. Human Machine Interaction (also abbreviated to HMI) is a key component of human factors. Designing or choosing an HMI that is appropriate for the context of use (such as “while driving” or “at a bus stop”) can have a decisive effect on the outcome.

Proper attention to human factors can enhance the safety, effectiveness and ease of use of Intelligent Transport Systems and Services for individuals and for widely different groups of users. A key point is the variability within users – and within specific groups of users, such as “car drivers”, “pedestrians”, “Traffic Control Centre Operators” or a “Mobile Safety Patrol”. Users have different needs and motivations. For example, the task to be performed by a cyclist is very different from that of a control room operative or a road maintenance worker.

The importance of the broader road transport environment within which ITS informs and assists users requires an emphasis on “user-centred design”. It is important that road users are involved in ITS design. A complete understanding of the tasks they need to perform and their scope for error is vital. The importance of piloting, feedback and monitoring in any ITS or other transport system design, its introduction and its operation cannot be under-stated.

Relevant ITS standards for HMI cover areas such as vehicle design, the design of infrastructure (signage for example), standards for ITS in control rooms, for tunnel design and management, and for public transport. The needs of vulnerable road users are especially important here.

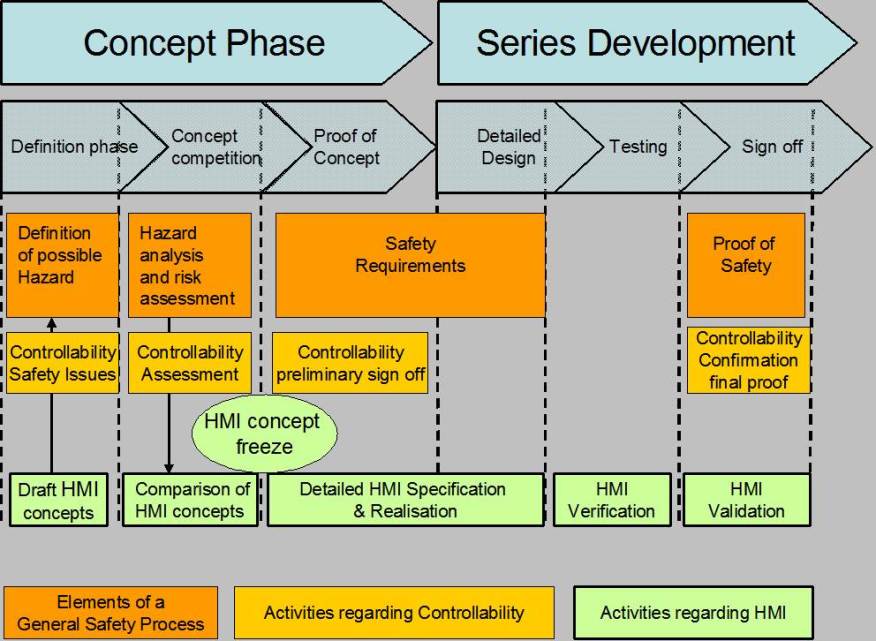

The design of the Human Machine Interface (HMI) has to support the user and promote safety in the transport environment. The following provides some key advice based on human factors principles:

Understanding who uses ITS and how it influences their behaviour provides a wealth of information which can be harnessed to improve the design, implementation and operation of ITS applications. Users are human and humans make mistakes! Some are quickly realised and may be corrected. There are also errors that may have wider consequences and safety implications.

Everyone is different. Some differences between people are innate and last a lifetime, some may come and go, and some may develop slowly over time. It is well known that physical characteristics such as strength and reaction time vary between individuals – but human behaviour in engaging with increasingly technological transport systems also depends on an individual’s information processing capacity. How users perform in their interaction with ITS will vary considerably. An individual’s performance will also vary over time depending on a complex interplay of factors.

Interaction between users is also an important issue. “User Groups” may help to distinguish users of ITS who have certain characteristics or factors in common – but still include a diverse range of individuals. An analysis of how individuals behave when interacting with other individuals, and how they behave as a group, provides useful insights which can help shape the policies adopted for Road Network Operations.

Stakeholders in the successful implementation of ITS-based systems and services include the Road Operators (ROs), their providers of technology and related services, and national and local government. The users themselves can be categorised in a number of ways – a basic one being:

These stakeholders, although not completely distinct, can be further disaggregated. Drivers, for example, can be categorised in many ways, according to:

Vulnerable Road Users (VRU) (See Road Safety) may include:

Road operator employees will include:

National and regional road authorities and those responsible for operations – the Road Operators – have a duty of care to the users of their road networks. Whilst people are individuals and will make their own decisions, they can be encouraged and enabled to adopt safe practices in the use of the roads. By taking account of human motivation and decision making, Road Operators are better placed to understand how people behave both individually and in groups – and how best to influence that behaviour in order to manage the road network.

In terms of ITS, the Road Operator should ensure that the information provided is as clear and correct as possible, and that the ITS provided is safe, well maintained and fit for purpose – so that it can be easily used.

The Road Operator is responsible for the work and conduct of their staff and this includes responsibility for any ITS they may use as part of their jobs.

The Road Operator needs to understand the tasks to be performed by its workers – and to appreciate the scope and consequences of user errors and how these can be avoided or their consequences mitigated

The Road Operator should consider the role of education and training for its workers. Education allows individuals to form mental models of why and how things work and may improve performance by reducing errors and increasing motivation. Performance generally benefits from training although “overtraining” and complacency/boredom may become a negative factor in some cases

Many countries have legislation concerning how disadvantaged users or those with special needs should be taken into account. Consideration has to be given to design of ITS for all types of users given the importance of creating an open and useable road transport system for all. Road Operators should ensure that ITS is designed to accommodate the full range of users wherever possible. If not, an assessment needs to be made about how those not provided for will be affected and whether the consequences are acceptable. If not, an entirely different solution may be needed.

These “design for all” considerations may conflict with economic or operational efficiencies. Depending on ownership and governance structures, the Road Operator may be subject to purchasing constraints (for example having to use a particular supplier) and this may limit the design choices for ITS.

As an employer of, for example, control room staff and road workers, a Road Operator will probably have statutory duties towards their workers in areas such as health and safety practices and the safe use of ITS.

ITS can provide much helpful information and assistance to drivers and other road users. It can also pose potential problems. Diverting attention to in-vehicle information and communication systems can detract from driving performance and decision making. This has led to some countries enacting protective legislation such as banning the use of hand-held mobile phones and texting whilst driving. The Road Operator may need to take account of this in the ITS systems provided to their workers and in their operating practices. They may also be made responsible for enforcing national laws on its roads.

The HMI principles described here are designed for Road Operators to apply in all countries. However, the application in developing economies may need to be tailored to the specific context. Some specific points to take in to consideration are provided below.

Developing economies may have a greater diversity of users, particularly in terms of educational provision. For example, the literacy level or level of familiarity with technology cannot be assumed to be the same as in developed economies and multiple languages may need to be taken into account.

The road environment and the balance of user groups varies considerably from country to country – for example, there may be a greater amount of animal transport, pedestrians and cyclists (vulnerable road users) and fewer drivers of motor vehicles. The mix of vehicles driven or ridden transport may be very different from that typically used in a developed economy, often with a greater proportion of powered two-wheelers (PTWs). Similarly, the infrastructure – for example, traffic control, may be less developed, particularly in rural areas.

Countries have different laws, but developing economies may be less advanced in terms of safety requirements and enforcement (for example concerning traffic offences and the use of mobile phones while driving). With different social and cultural background, the norms of behaviour by road users and their attitudes towards the rules of the road may deviate widely from safe practice. The extent to which economic forces and peer pressure drives behaviour may need special attention in modelling user behaviour.

The degree of investment in ITS technology and services, its reliability and that of its powered energy and communications may be more variable than in developed economies. Lack of reliability is likely to affect deployment of ITS and the behaviour of users. Developing economies may not have access to trained human factors professionals to advise Road Operators in aspects of user behaviour. (See Building ITS Capacity)

Designing an ITS product, system or service for the people who will use it is not simply a case of designing to a required specification for a ‘standard’ person, as there is no such thing as a standard person – everyone is different. Whilst people possess certain qualities and limitations that apply, at least in part, to everyone, they are by no means universal. For example, it is possible to quantify reasonable upper limits for human visual performance – but some people cannot see anything at all, others may have blurred vision, and for those who see in sharp detail there may still be issues such as colour blindness affecting their vision. Some differences between people are innate and last a lifetime, some may come and go, whereas some may develop slowly over time. Whatever the reason, differences between individuals must be accounted for in any design, and this includes ITS.

Whilst human variability is vast in scale, there are certain key areas that are likely to influence ITS practitioners in their work.

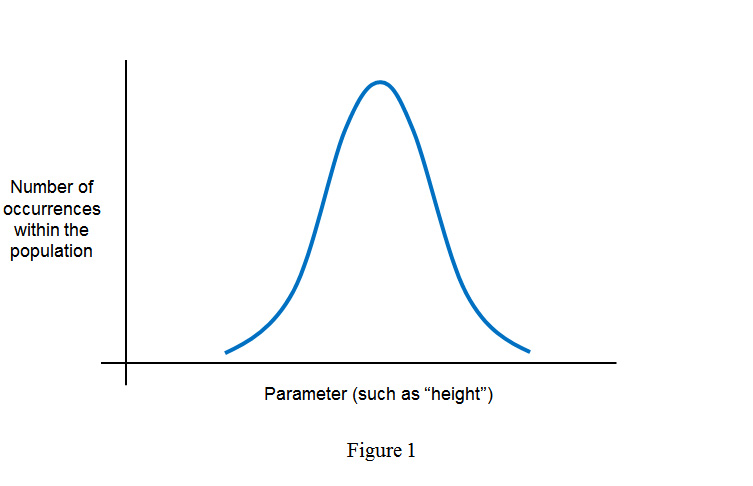

The vast majority of quantifiable human attributes (especially physical characteristics) follow what is known as the ‘normal’ distribution. This is a distribution seen throughout nature and is represented in the figure below. It shows that the average value within a population (for a criteria such as height) will be the most common, with more extreme (large or small) values being progressively less common. There is no such thing as an average person as there is almost certainly nobody alive that is exactly average in every conceivable parameter. Instead the population is comprised of individuals who may be higher up the distribution on some parameters and lower down the distribution on others.

Natural variability in the population

It is unavoidable that as people age their senses and faculties start to deteriorate. Eyesight and hearing are amongst the most prominent in terms of the senses, but mobility will also usually be affected – and at some point most people will begin to experience a slowdown in their speed of mental processing. The ability to learn new skills quickly will also reduce over time. The converse of this is that the faculties of younger road users may still be developing. Basic senses in younger people may be well functioning, but cognitive abilities may not yet be at adult levels, which can impair decision-making. Younger users will also typically be smaller and less physically developed than adults.

Differences based on social and cultural background can sometimes be pronounced – and although generally harder to quantify than age-related decline, their impacts can be predicted at some level. Key considerations in ITS will relate to factors such as attitudes towards different road users, acceptance of technology and driving conventions. For example, cyclists and car drivers often experience confrontation based on different perceptions of each other. General attitudes of different user groups can often be determined by engaging with relevant users, to understand and help predict and take account of potential conflicts – whether they be within user groups, between user groups, or between users and technology.

Four high-level principles help guide those working with ITS:

If someone was to design a door it would clearly be foolish to use an average person’s height to determine the door height – since it would not be usable by at least half of potential users. Instead the door should be designed to accommodate the tallest users as there are no detrimental effects for shorter users. In the same way, when designing an overhead gantry-mounted variable message (VMS) information screen, the text should not be at a font readable only by those with 20:20 (average) vision. By making the text larger, a greater proportion of road users are taken into account and the text is easier to read by all.

There may be times when it is not possible to accommodate everyone at the same time. In such cases, the principle of designing for the 5th-95th percentiles of the population is generally adopted. If, for example, someone was designing a forward/back seat adjustment mechanism for a car – a key parameter will be the leg-length of users. If all users were ranked according to leg length:

Adopting the 5th– 95th percentile principle means that the seat is made adjustable so as to be used comfortably by the middle 90% of users in terms of leg-length. If it is possible to design a seat that is practical and can accommodate the 1st– 99th percentiles, this would be even better.

Given the importance of creating an open and useable road transport system for all, traffic planners, engineers and designers should seek to accommodate the full range of users wherever possible. If not, consideration must be given to how those whose needs have not been taken into account will be affected – and whether these consequential effects are acceptable. An entirely different solution may be needed.

If the principles outlined above are applied and an effective design is established for one application, it may not be the case that this can simply be transferred to other applications. An example could be a system that has been implemented successfully in one country and is being considered for use in another country. Cultural differences between users or technical differences in the transport infrastructure may mean that users interact with the system in a different way – and that there are unintended effects that had not previously been identified in the original application. Variability may also be an issue where a system is already established. Changes in user populations can happen over time and changing external factors may alter the overall operation of the system. Whenever updating or introducing a new system, it is useful to conduct user testing.

The following universal aspects of human variability should always be taken into account in the design and operation of any facility or service that will affect road transport systems:

Human performance describes how easily and efficiently an individual achieves a certain outcome – such as navigating to an address, crossing the road or buying a bus ticket.

Human performance is based on a physical and cognitive (mental) control “system” that is the result of millions of years of evolution. Human action is largely effective and adaptive even when carrying out complex tasks – but humans are not machines – whatever role they are undertaking. It is important to understand the limits and the variability of human performance so that transport systems and ITS can be designed and operated accordingly. Performance varies between people and an individual’s performance also varies depending on a complex interplay of factors. These variations can make or break the success of new applications of ITS, such as cooperative driving. (See Coordinated Vehicle-Highway Systems)

People make errors! Sometimes it is useful to draw a distinction between “slips”, “lapses” and “mistakes”. Slips and lapses are skill-based errors. Slips occur when there is a mismatch between someone’s intention and action – intending to do the thing but doing it incorrectly. These are often quickly realised and may be corrected. Lapses are when a user forgets to do something or their mind goes blank during a task. Mistakes, on the other hand, result from some misperception or misjudgement and are decision-making errors – doing the wrong thing but believing it to be . These are often much harder for a user to identify and correct. We cannot predict exactly when errors will occur but there has been considerable research concerning their context and likelihood.

Performance is affected by specific impairments that people may have – these can be (semi-) permanent, such as a broken arm or colour-blindness or temporary. Examples of temporary impairment include tiredness – which is a particular issue for shift workers. Individuals can also be intoxicated or unwell which can affect their performance.

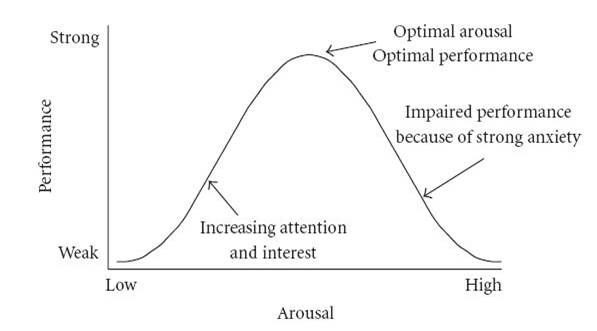

Human performance varies depending on arousal (excitation level). Individuals can be under-aroused (sleepy, dis-engaged) or over-aroused (excitable, anxious). Individuals perform at their best when at neither extreme.

Arousal/Performance curve

Performance often depends on motivation (See Motivation and Decision Making), which can also interact with arousal. Individuals tend to perform better when they are well-motivated.

A control room operator using a terminal, or a public transport user reading dynamic signage, may concentrate on the terminal or the sign as a single focus of attention. This contrasts, for example, with a driver observing the road whilst simultaneously adjusting the car entertainment system. Sharing of attention between two tasks is known as the “dual task paradigm”. Performance when undertaking a single (or primary) task is usually better than when trying to undertake another (secondary) task at the same time – because mental resources have to be shared between the tasks.

It is well known that performance varies between individuals. Issues such as strength, reach, endurance and reaction time are examples of physical ergonomics which can be measured for different groups.

Human performance in the context of today’s increasingly technological transport systems also depends on an individual’s information processing capacity. To a large extent this is affected by how an individual’s various physical senses or “channels” – such as visual and auditory – handle the streams of information encountered. All channels require mental resources to process information and these channels can become overloaded. There is more interference within channels than across them. For example, talking whilst engaged in a control task is easier than operating two controls or holding two conversations simultaneously.

Research suggests that not all mental resources are equal and “multiple resource theory” accounts for how it is sometimes possible to do two things at once – as long as specific limited mental resources are not required for both tasks.

Training can greatly affect performance through repetition, practice and familiarity. For example, a public transport user familiar with a ticket machine can make a purchase more quickly than an unfamiliar traveller. Some activities, such as the use of the clutch when driving, can become almost unconscious requiring very little effort. Performance generally increases with training although “overtraining” and complacency/boredom can become a negative factor in some cases.

Education allows individuals to form mental models of why and how things work and may therefore increase performance by reducing errors and increasing motivation.

Expect and allow for variability between people and for a variation in one person’s performance/ability at different times and in different circumstances. The variability may be obvious (such as age, size, physical disability) or may not be. Where possible, design for the least able and most endangered. (See Diversity of and user groups)

People make mistakes, so it is essential that ITS is designed so that systems and processes minimise the possibility of errors and provide opportunities to recover from them. (See Automation and Human Factors). Task and error analysis may be helpful. (See Human Tasks and Errors). Particular care needs to be taken when an individual’s mistake could have safety consequences for themselves or other road users.

Driving – and Powered Two-Wheeler (PTW) riding – is a complex and safety-critical task which requires physical and mental resources. Driving skill and performance can be improved through education and training. A minimum level of performance should be required at all times whilst driving. Drivers’ skills need to be tested, at least initially, and a minimum standard should be enforced. New technology can introduce tasks additional to driving, such as making a phone call – which can impair driving performance and should be discouraged on grounds of road safety.

Vulnerable road users – such as cyclists and pedestrians of all ages – will vary, for example, in the degree of their physical movement, direction-finding and road awareness. All information and directions aimed at them should be designed to be simple, unambiguous and easily perceived.

ITS infrastructure (including signs, payment facilities, speed limits) should be designed to take account of the intended user population and the variations in performance that they have. Many human factors standards and guidelines are available which are suited to different ITS applications. (See HMI Standards and Guidelines). Using internationally agreed standards and guidelines for HMI is recommended – they help to promote familiarity and often provide multiple signals to the brain for recognition (for example, use of colour and shape).

When possible, new designs should be simulated and trialled with the intended user population to ensure that human performance shows that they can be easily understood and used. (See UK Smart Motorways )

ITS infrastructure should also be designed to take account of the performance limitations of those personnel involved in their maintenance. (See Work Zones)

Public transport operators need to be mindful of the broad range of human performance and specific disabilities that may impair performance – when designing or purchasing systems such as display screens and ticketing facilities to: (See Diversity of Users)

The Road Operator will need to set standards, provide training and undertake regular performance reviews of control room operators. (See Traffic Control Centres) They need to:

Human factors professionals can assist in designing work and shift patterns to minimise performance degradation. (See Infrastructure)

The road should be considered a potentially hazardous working environment for personnel such as maintenance and emergency response workers. Road Operators should:

Human factors professionals can assist in designing work and shift patterns to minimise performance degradation.

The “user friendliness” of the road network depends on a complex interaction between the technical systems – such as traveller information, route guidance and traffic control – and the road network users. Ultimately, people are individuals and will make their own decisions, but there are many theories and models that can help us to understand individual motivation and the effect this has on behaviour.

By taking account of human motivation and decision making, Road Network Operators should be better placed to understand how people behave both individually and in groups – and how best to influence that behaviour in order to manage the road network.

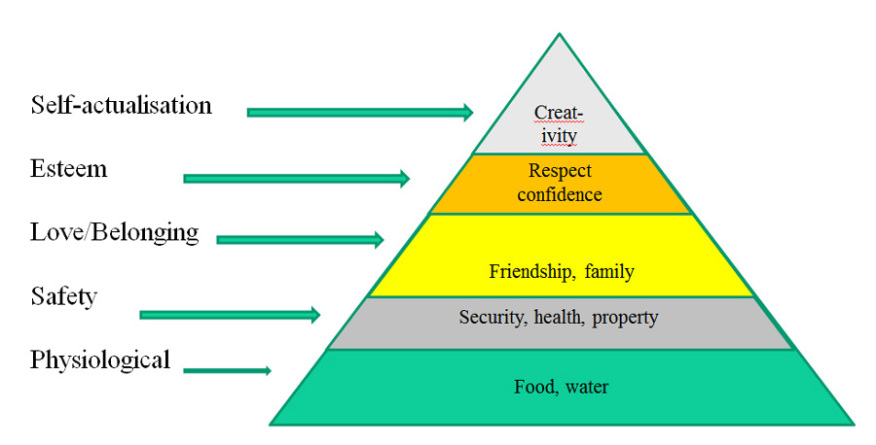

The psychologist, Maslow proposed that humans have needs that influence their behaviour, which can be arranged in a hierarchy. Once a need is satisfied, then behaviour is influence by the next (unsatisfied) need in the hierarchy. The most basic are physiological needs (such as food and sleep). Once these are satisfied, safety needs take over and so on.

Hierarchy of Needs

Expectancy theory says that choice or behaviour is motivated by the desirability of outcomes. In general people prefer to avoid negative consequences more than increase positive consequences – for example, to arrive at 08.45am for a 9.00am appointment is of minimal benefit but arriving late may be of considerable dis-benefit.

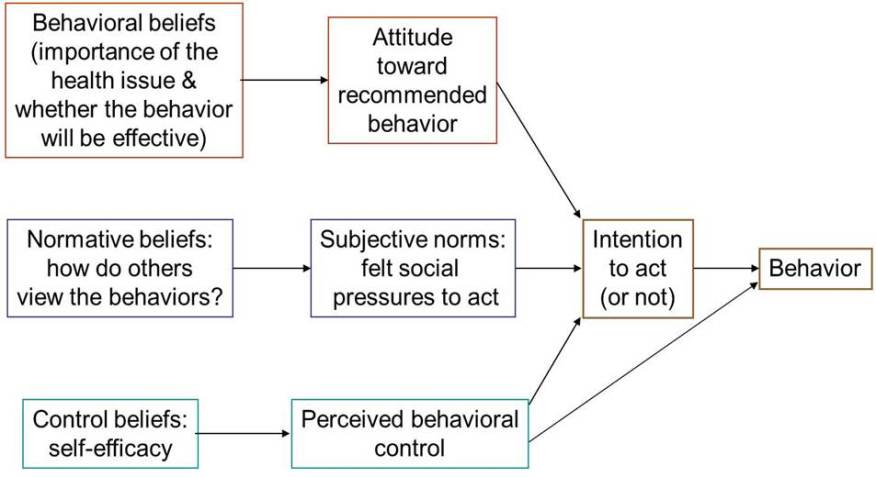

According to the theory of planned behaviour, an intention to behave in a certain way is influenced by three things: the expected outcome (positive or negative), how others will perceive the behaviour and a judgement about one’s capability to carry out the behaviour. It seems that there are “boundaries” within which people feel they can and should act and areas where they feel they cannot. In part, this depends on having “permission” to act in a certain way – whether this is permission one gives oneself or whether it is permission granted by others. For example peer pressure can have a profound effect on young male drivers’ behaviour and their willingness to comply with traffic laws.

Planned behaviour

Incentives and positive reinforcement make a behaviour more likely in the future. Benefits that appear certain and immediate are generally preferred to those that are less certain and more distant. This is called the saliency of benefit.

People have an innate drive to be self-determined – they mostly prefer to be in control and will seek information in order to make decisions. This can be used to advantage in Road Network Operations by providing advice to road users and other travellers. Their trust in information (its credibility to them) depends on many factors including:

In general, people have a poor appreciation of risk (consequences and probabilities), and especially of very small risks. Events that can be more easily brought to mind or imagined are judged to be more likely than events that cannot easily be imagined. This is called the availability bias. Press reports, for example, tend to favour Bad News stories, which promote negative expectations. The managers of Traffic Control Centre operations will be acutely aware of this.

People do not always make choices that are in their best long-term interest. Sometimes “wants” are satisfied before “needs”. So, people are not always economically rational even when all necessary and consistent information is presented. The road users’ response to information messages may differ from what is intended by the Road Operator.

Few individuals constantly seek new experiences. For most there is a tendency to keep doing things in the same way. This is called inertia (an analogy to mechanics). So, people either do not undertake some new activity or continue to do the activity in the same way. To a large extent, these habits are a coping mechanism for the plethora of choices in everyday life.

Decision making also depends on the user’s willingness to seek out all required information (if it is even available). So, a typical approach in many situations is “satisficing” - seeking solutions that are not necessarily optimal but are “good enough”.

One theory proposes that people aim to reduce dissonance (degree of discomfort) between their view of the world and their actions. This can lead to “post-hoc” (after the event) justification of a decision made.

Related to this is a tendency for people to display confirmation bias – a tendency to seek out information (and to preferentially trust that information) that confirms an existing belief, rather than new evidence that may contradict that belief.

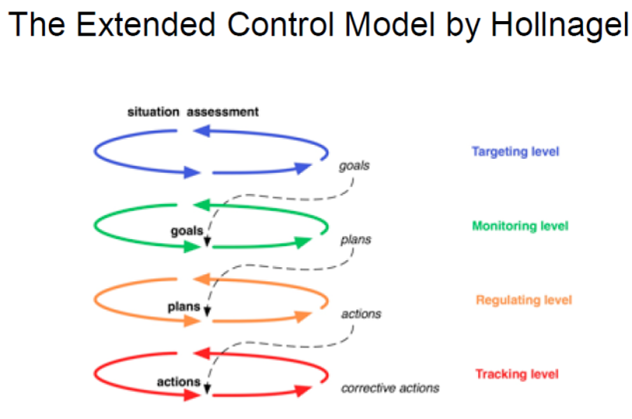

In the driving context, Intelligent Transport Systems (ITS) can provide information and assistance to drivers and can play a part in their decision making. Research has led to various models – one model describes driving decisions at three levels:

An extension to this model considers driving decisions at four levels with feedback and interaction between them.

The Extended Control Model (reproduced with permission from http://erikhollnagel.com/ideas/ecom.html)

Individual drivers exhibit a range of driving behaviour and styles of driving. Driving can also be considered as a social activity. Interactions between vehicles and between vehicles and other road users are largely interactions between people. An aggressive driving style, particularly in a cooperative driving culture, may be highly offensive. The term “road rage” has been coined to describe extreme feelings or behaviours aggravated by, for example, other road users’ behaviour or driving situations such as congestion.

ITS can provide much helpful information and assistance to drivers. It can also introduce potential problems. Attention to in-vehicle information and communication systems can detract from driving performance and decision making. Although ITS can provide assistance to reduce the drivers’ workload, it is known from research that a sustained low workload (underload) can lead to boredom, loss of situation awareness and reduced alertness. It has been observed that the greater the number of support-system functions which have become available through ITS, the higher the risk of drivers losing competence, which can sometimes be combined with their reliance on ITS functionalities. (See Driver Support)

Road users typically believe they have an implicit contract with the road network operator. This (in their mind) might include keeping the traffic flowing, maintaining the cycleway, and providing safe and adequate public transport. As a minimum, road users’ basic needs should be considered – such as food and toilet facilities and rest stops for longer journeys.

Anger and frustration can arise if the service quality falls below road users’ expectations. ITS can help to manage expectation – for example by providing information about service quality and frequency. This information needs to be available to road users before their journey (for example on the internet, or printed information), and during their journey (for example on signs, notices, mobile devices). ITS, and communication channels more generally, might also be employed to counteract “Bad Press” stories about the road network.

Road users develop habitual behaviours, partly to reduce overload and anxiety about unknown situations. This “learned behaviour” leads to an expectation of permanence and consistency – so if something changes there can be surprise, anger and frustration. ITS, if well designed, can be very helpful in reducing these negative emotions and provide information likely to influence behaviour. (See Traveller Services)

Road closures and changes to schedules should be made available through both ITS and conventional means well in advance, if possible, using multiple information delivery mechanisms.

ITS is particularly useful for providing real-time information about maintenance activities and disruptions to service levels such as traffic congestion. Road users can become anxious and frustrated if they do not have any scope to affect their situation – or if no information is provided (such as the reason for the delay, how long it will be, and what the alternatives are).

ITS information can provide additional confirmation of the situation, sufficient to nudge behavioural change. It should be presented in a clear and authoritative manner. The information should be consistent with other information (unless it is newer and better than existing information).

Apart from a sole road user on an open road, most road use occurs in the context of other road users and so can be considered as a group activity. Social psychology and game theory, involving cooperation and competition, provide useful insights which may be of value to the road operator:

It is noticeable that there are different driving styles in different countries (for example, more or less-aggressive driving, queuing practice and turn-taking, use of mobile phones). Again, ITS can be used to rapidly contain situations or reinforce positive behaviour so that it becomes normalised.

When users of ITS have a choice they choose to engage and adopt new technology based on a number of factors:

Users interact with Intelligent Transport Systems (ITS) using senses such as sight, hearing and touch. For example – for an ITS-based Variable Message Sign, to be effective, it has to be visible and the message readable/recognisable.

User engagement with ITS and the various types of services that ITS provides, is of special importance to the suppliers of ITS to Road Network Operators – and to the road users themselves, either indirectly or directly. These include:

The design of the HMI for ITS technology, in terms of how it affects the dialogue with the user (the software for example) is very important to promote ease of use. For an interactive device, important dialogue issues include: length of “timeouts”, language used and menu structure.

The context of use is an important consideration when designing how users interact with ITS. An ITS device should not be described as “useable” or “ergonomic” without also describing the context in which that use takes place.

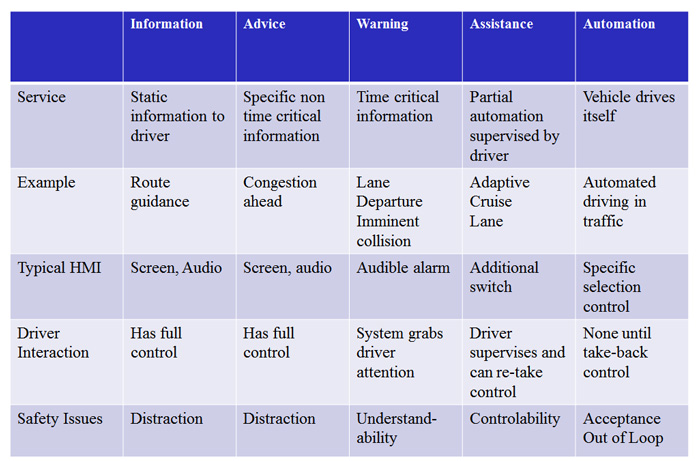

Users engage with ITS to obtain different services – such as information, warnings or assistance/automation. The human factors issues associated with these different “levels” of interaction are very different and they may have safety implications. Appreciating the key differences and understanding these issues can help the road network operator to purchase, design and implement appropriate ITS.

Road Operators have a duty of care to the users of their road networks. Whilst people are individuals and will make their own decisions, they can be encouraged and enabled through ITS to adopt safe practices in the use of the roads. In terms of ITS information provision, the Road Operator should ensure that the information provided is as clear and correct as possible – and that the ITS provided is safe, well maintained and fit for purpose so that it can be easily used.

Particular attention should be given to safety-critical tasks. The Road Operator may wish to introduce driving restrictions in some contexts where there is a particular risk. Examples might relate to health and safety considerations such as:

The Road Operator has responsibility for the work and conduct of its staff and this will include responsibility for any ITS they may use as part of their jobs. Choice of HMI is a specialist area, and advice from human factors professionals is recommended

The Road Operator should be mindful of human factors when designing or procuring ITS. How ITS services are implemented determines how easily they can be used. This influences user acceptance and adoption – as well as adaptation of behaviour and overall safety.

The introduction of new technology, such as ITS, tends to allow not only more efficient ways of undertaking tasks – but completely new ways of working. For example, the availability of real-time travel information on a personal hand-held device changes information needs – and relationships between the user and the providers of transport services. Information services may also pose challenges of security and privacy when individual data is stored and processed as part of the ITS. (See Legal and Regulatory Issues)

New HMI may lead to the development of national and international laws and vehicle regulations. New technology that has emerged in recent years includes Bluetooth headsets for mobile phones and head-up displays within vehicles.

Automation, especially of road vehicles, is likely to involve institutional issues. There may be some public distrust of automation, particularly around road safety and potential job losses (for example, automated truck platoons may require fewer drivers). Automated driving may require the development of national and international laws and vehicle regulations. (See Automated Highways)

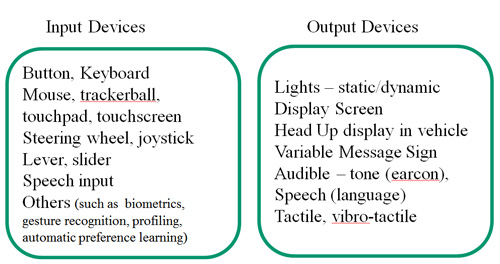

Humans can interact with the outside world, including ITS, in myriad ways and there is a wide variety of technology available to assist this interaction. The most common HMI components used are described here. HMI elements – good, poor and indifferent – are invariably present in computer systems and ITS. For example:

Public displays may also incorporate important HMI features – such as:

It is a commonly-held ‘truth’ that people have five basic senses:

In fact people have others senses as well, including: vestibular (balance and movement), kinaesthetic (relative position of parts of the body), pain, a sense of temperature and a sense of time passing. All these allow people to interpret the world around them, at different levels.

There is a wide range of human machine interface components to support the interaction between road users and ITS.

Engagement with ITS – HMI components

Use of hardware (such as buttons and a display screen) allow road users to interact and to develop a dialogue with the ITS technology. The extent to which the dialogue is efficient and effective (and liked by the user) depends both on the detailed design and performance of the interface hardware and also the design structure of the dialogue.

The designer of the HMI has a very wide range of choices. For example, in hardware design, buttons can be “latching” (they maintain their state after being activated) or “non-latching” (momentary) with different sizes, shapes and clearances to other buttons, different levels of resistance and sensitivity. The hardware design may also take account of implicit associations and knowledge of users (such as a familiar shape or icon and colour – such as red for danger).

The design of the dialogue (its structure and management) is also very important to promote ease of use. Important issues include: length of “timeouts”, language used and menu structure.

Although the design of the HMI of vehicles is the domain of the automotive manufacturer, in-vehicle HMI is often supplemented by drivers with the addition of mobile communications and information systems. These may or may not be designed for use while driving and their use can have a significant effect on drivers.

Choice of HMI is a specialist area, and advice from human factors professionals is recommended. The HMI should be based on:

There may be a trade-off between ease of learning and ease of use.

Try it with new users – what is their experience? (See Piloting, Feedback and Monitoring)

To be effective, all transport signs need to be noticed, understood and followed. Much has been studied and written about the human factors of road signage. Signage should be considered as part of an overall information provision strategy for road users. There will also be human factors considerations in its construction, installation and maintenance.

Variable Message Signs (VMS) are a typical form of ITS, particularly used on interurban roads to convey messages to drivers. Key considerations for VMS include:

Design of vehicles including their HMI is the domain of vehicle manufacturers who consider the “look and feel” of their vehicle’s HMI as part of their brand image.

Information and communication systems may be factory-fitted, fitted as an aftermarket option or (more commonly) brought into the vehicle by the driver. Examples include SatNav guidance systems and fee collection transponders. Some countries have legislation restricting the use of specific devices such as hand-held mobile phones. The HMI of in-vehicle devices may or may not be suitable for use while driving and road operators should be aware that use of such “secondary” interfaces by drivers may contribute to inattention and distraction.

Some Road Operators and other information brokers have sought to use data provided by large numbers of transport users to help road performance. This is called “crowdsourcing” which uses location and communication information from smart devices. The engagement of users may be implicit as a result of their use of other services, or may require more explicit participation. Increased engagement and richer data may be sought by offering interaction and competition (“gamification” – turning it into a game) or by using user-derived content from social media. There are privacy issues to consider, but road users may be willing to engage in services that offer benefits to them, such as ride sharing.

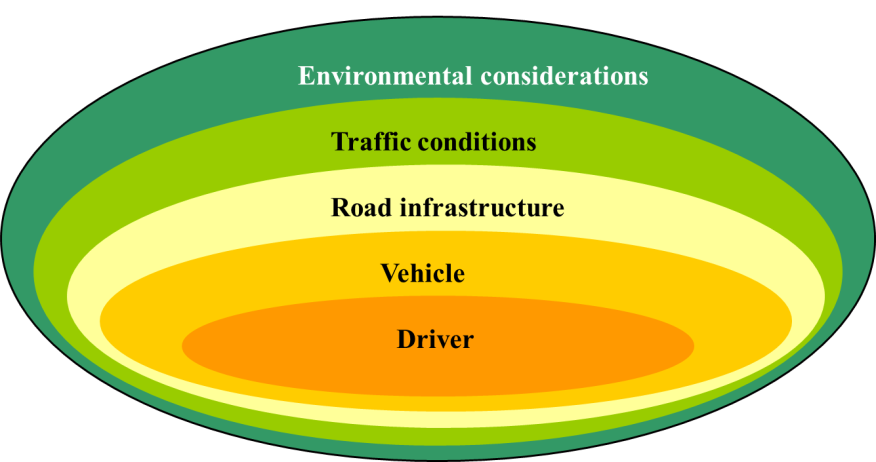

The context of use describes the conditions and environment in which users interact with ITS. Examples include:

The context describes the main issues likely to have a bearing on the interaction such as “who” “when” “where” and the environmental conditions.

The context of use is an important consideration when designing how users interact with ITS. It can affect motivation, performance, attitudes and behaviour of the users and the overall efficiency and effectiveness of the interaction. An ITS device should not be described as “usable” or “ergonomic” without also describing the context in which that use takes place.

Any measurements of usability (user-friendliness) should be carried out in an appropriate context and include a detailed description of that context.

Part of the context of use includes the user(s) themselves – who can be characterised in many ways including their knowledge, skills, experience, education, training, physical attributes, motor and sensory capabilities. The user’s experience is the context of events that have immediately preceded this interaction with ITS. (See Diversity of ITS Users)

The user can also be identified in terms of their current mood, time pressure and their goals in interacting with the ITS.

Tasks are the activities undertaken to achieve a goal and are part of the context. Issues here include the frequency and duration of the tasks to be undertaken. (See Human Tasks and Errors)

The technological environment includes the software and hardware of ITS. For example, interacting on a small mobile screen or a full screen are different contexts. The speed of processing and the characteristics of a keyboard can all affect the usability of ITS. The availability of reference material/user guides and other equipment may also be relevant.

For some interactions with ITS, the organisational context may be relevant such as the attitudes of an organisation’s management and employees towards the ITS, the way task performance is monitored and any internal procedures or practices. The structure of the organisation, reporting and reward arrangements, the availability of assistance, and frequency of interruption – are all relevant factors.

Interaction with ITS can be different depending on whether it is an individual or group activity, and whether it is undertaken in public or private. For example, use of an individual ticket machine may involve some social pressure to complete the interaction quickly if there are others waiting to use the facility. Driving is a kind of social activity where there may be both cooperation and competition.

This includes a number of environmental issues:

Another way of representing the various contextual factors is the 5W+H checklist:

Always investigate and document the context of use when designing how users interact with Intelligent Transport Systems as ITS need to be designed for specific contexts.

The following five steps are recommended in specifying the context of use for an ITS (product or service):

Checklists can be helpful in describing the context of use. Diagrams can also be helpful. The example in the figure below concerns a driver’s use of an in-vehicle ITS.

Context of ITS use within a vehicle by a driver

Develop an evaluation plan for the ITS (system or service) and then undertake trials in realistic contexts. Based on feedback and results, re-design the system or service or modify the context of use to achieve the required level of usability.

In the longer term, the Road Operator should set up mechanisms for monitoring ITS use and receiving feedback from users. (See Measuring Performance and Evaluation)

Particular attention should be given to safety-critical tasks. The Road Operator may wish to consider imposing restrictions on interactions in some contexts of use where there is particular risk. Examples might relate to health and safety considerations such as:

ITS can support users with information and warnings, and can provide various levels of assistance and automation depending on the service.

The human factors issues associated with these different “levels” of interaction are very different and these may have safety implications. Appreciating the key differences and understanding these issues can help the Road Operator to purchase, design and implement appropriate ITS.

The manner in which ITS services are implemented impacts on their ease of use. This greatly affects user acceptance and the degree of behaviour adaptation, as well as overall safety.

One characteristic of ITS is the level of support provided to the user. Using a five-fold classification, example ITS services are shown here:

There are different levels of automation for road vehicles:

The human factors and safety issues are different for each different level of interaction or level of automation. The design of the HMI must be different for the different levels – in order to best support the user and promote safety in the transport environment.

The figure below provides a summary of the levels of support and HMI implications in the context of vehicles and driving. For further information see Driver Support

Levels of ITS support to the driver

It is important to identify the level of support that ITS is providing to users. Task and error analysis may be useful. (See Human Tasks and Errors)

Secondly, it should be appreciated that the human factors and safety issues are different for each different level of support – so the design of the human machine interaction (HMI) must be different for the different levels, to best support the user and promote safety in the transport environment. (See Road Safety)

Road users can access information in a variety of forms and via different sources. Particular safety issues arise when users, such as drivers and road workers are also involved in safety-critical tasks such as driving or operating machinery. Here, distraction can be a problem so information has to be designed and delivered so that it can be easily used – in the specific context of use. Human factors guidelines are available to assist. Road Operators may wish to restrict access to distracting sources of information to improve safety or design procedures so that information can be accessed safely.

Advice is more specific information that implies or suggests a particular course of action, such as suggesting an alternate route in times of congestion. Understanding and comprehension of the advice is a key issue. The information supplier should provide advice in a clear way which is likely to be easily understood by the intended users. The user response should not be assumed – but should be observed.

Warnings are specific pieces of advice that may require action to be taken in a time-critical way (within a few seconds). Road users have a short period of time in which to understand the warning and take appropriate action. Suppliers of warnings – such as the operations staff at a Traffic Control Centre – should carefully design and test them (to ensure they are well understood and create the intended response) and should consider practice and training so that users become familiar with how to respond. The user response should not be assumed – but should be observed.

Assistance systems automate part of a road user’s task under their own supervision. Driving assistance systems which partly automate the driving task are becoming more common. Specialist machinery used in road construction and maintenance is also becoming more automated. The line between assistance and automation is not completely clear.

Whilst assistance and automation can provide operational and safety benefits, there are several potential safety issues that need to be considered. A key issue is that users over-trust the assistance/automated system and may not appreciate its operational limits. Training and experience should assist here. A related potential problem is poor supervision of the ITS service delivery. (See Automation and Human Factors) It may also be that users become de-skilled as a result of reliance on the assistance – and so are not well prepared to take back control if necessary. Training and practice are good ways to mitigate problems.

In the modern world, many processes are automated by machines. Whereas people would previously have been responsible for completing each individual process, the role of the person is typically now limited more to monitoring the machines that undertake those processes. The idea is that machines are employed to do the simple, repetitive tasks at great speed – and a person is on hand to sort out any problems that might occur. In theory this plays to the strengths of both machines and people. The (so called) “irony of automation” is that the human takes on the role of system monitor – and that this role is far from suitable for human attributes.

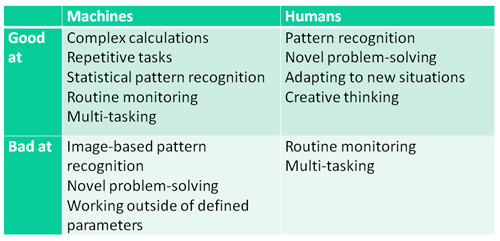

People and machines are good and bad at different tasks and roles. The figure below highlights some of the key distinctions:

Roles Suited to Humans and Machines

In ITS the role of automation is often to remove from the user responsibility for tasks that people generally find difficult or mundane – so they can concentrate better on tasks which either cannot be automated or cannot be automated efficiently and effectively.

It may not always be easy to make a clear distinction in the appropriate division of labour. It may be that a system can only automate parts of a task, or that there is an output from an automated task that must be fed back to the user at some point. Issues can arise if the division of labour is such that a user is required to perform a function for which they are not suited, as a direct result of that division.

Even if people are given roles suited to their skillsets, and tasks are suitably reallocated for automation so that the user is able to only consider the critical tasks – performance may be compromised if the user is so far removed from the task (“out of the loop”) that they are unable to intervene effectively when required.

People perform poorly when overloaded, but performance also drops off when under-loaded as it can cause the user to switch off mentally. It may be that any corresponding loss of attention means an operator fails to spot an important development within the system. Even if operators are alerted to an important development by an alarm – their understanding of what needs doing to rectify the issue may be impaired if they have not been kept sufficiently in-the-loop to maintain their situational awareness. This awareness is essentially the user’s understanding of: what is happening within the system, what will happen next and what the implications are. Loss of situational awareness could arise through poor task allocation within the system, as a result of cognitive under-load or through the user placing too much trust in the system to perform as expected.

If a situation requiring action by the driver arises, automation may mean that the system warns that an intervention is necessary – even if the user is sufficiently alert and knows what to do. If the alert is not given early enough, the operator may be unable to act, despite knowing what to do in principle.

Automation can have negative consequences and designers will need to consider the possible implications of automation before introducing it into any design. Correct use of automation can prove extremely useful to the operator and to overall system performance. Transport systems and networks are often highly complex and ITS offers the potential to use technology to simplify aspects of these systems from the perspective of the user. Automation can be a useful means of reducing the overall complexity of the system so that individuals are able to focus more clearly on the most important processes. The key requirements in order to be able to do this effectively and safely are effective task allocation and the avoidance of overload or under-load.

Ideally, designers should seek to obey the following principles:

To avoid overload/underload, designers should also take account of the following principles:

The complexities of transport and logistics can be approached by using systems engineering methodologies and user participation in the design work. The Road Network Operator needs to understand fully the total system structure, its dynamic characteristics and the role and responsibilities of its different road users. It is only then that a proper Human-Machine Interaction (HMI) design can be accomplished with positive user acceptance and operational success.

Analysis breaks problems into their parts and attempts to find the optimum solution. This process of breaking apart the whole, however, neglects the interrelationship between the parts – which can often be the root cause of the problem. The “systems” approach argues that in complex systems, the parts do not always provide an understanding of the whole. Rather, in a purposeful system, the whole gives meaning to the parts.

In order to tackle the sometimes contradictory interests of society and individuals, systems engineering methodologies can be applied. An ideal systems approach would start with the analyses of both the users and the problems which these user groups experience in traffic and transport. Procedures should guarantee that the results of these analyses are then used in the design process itself. The introduction of a user-oriented perspective to Intelligent Transport Systems (ITS) has similarities with the introduction of quality assurance procedures found in most industrial activities.

There are other industrial elements of the design process, which have to be included in the required human factors work. They focus on the practical realisation of basic ideas of problem solving which firstly have to be turned into functional concepts. A phase of implementation of these concepts into user-accepted solutions follows. This is often a trade-off between system features and system costs. The features (or benefits) are composed of usability, utility and likeability – whereas the efforts to learn and use, the loss of skills, new elements of risks introduced, and the financial costs constitute the cost elements. The use of human factors knowledge is crucial when high usability is sought.

The difficulty of identifying variables to reliably measure all these elements – is evident. The principle of user acceptance is an approach that clearly highlights all the diverging elements that could, would and should influence the design process. It can simply be stated that if the features are valued higher than the costs (using a weighted criteria/cost function) the solution is acceptable and will be purchased – and hopefully used. Market place stakeholders – such as end-users, customers and consumers must be involved.

New products or solutions in ITS are very seldom developed to solve or meet completely new problems and needs. Instead, better performance of already existing solutions is often the goal. It is also clear that old solutions and products will co-exist side-by-side with new ones. The penetration of new technology in society is often very slow and starts with people that can afford to be “modern” and the most up-to-date. Therefore the design must allow parallel operation of the old and the new, and some form of step-by-step development must be used. Other elements to consider are that the long term goals of systems for traffic and transport are usually societal, while the short term (market-oriented) are individual in that they try to create and meet an instant demand. This inherent conflict must be addressed and needs to be resolved at an early stage of the implementation process.

The Road Operator is well-placed to take a strategic and user-centric approach to the design and introduction of ITS. The interactive design process that is required may appear to take a great deal of time and resources but the benefits will become apparent and should quickly, outweigh the upfront costs.

The Road Operator has the opportunity to work with others on ITS innovations that promote and develop integration of transport and other services – to provide additional benefits.

Before introducing ITS or any new technology, or undertaking extensive field trials, it is invariably beneficial to pilot the system or service with a small group of users before more widespread deployment. This approach is part of user-centred design and allows any problems to be addressed, avoiding embarrassing and expensive mistakes.

Encouraging feedback from users and providing suitable mechanisms for monitoring use of ITS allows those responsible for ITS operations to better understand the experience of both occasional and experienced users. This may show how the use of ITS is changing over time (because of changes in other parts of the transport system or the environment) and provides advanced information about necessary modifications, including possibly re-design of the ITS.

ITS can, if introduced through a sufficiently wide systems approach, assist users – by providing a measure of integration within and across modes of transport (for example by combining tolling, parking and public transport ticketing). It can also assist with wider common service provision between transport and other urban facilities such as energy services. These different modes of transport and wider urban services typically have different ownership, governance and objectives which present barriers to integration and enhancement of user services.

The rationale behind the development of ITS is the need for high efficiency and quality in new and innovative transport services. The goal of these services is either to meet a certain need for the movement of people and goods – or to supply a specific endeavour (or activity) with the correct amounts of its necessary components at the time and at the location. These activities are called transport and logistics respectively. By implication, the design of these services will include modern information and communication technologies (ICT) for the exchange of information in real time and the result is an “intelligent” transport system.

From their everyday activities, people identify needs for movement between specific locations and become travellers. They engage in trip planning and, if successful, a trip plan will be created by linking a sequence of transport options to serve the journey – if necessary based on different transport means. These transport options can either be chosen from available information (in timetables, for example) or can be made known to someone (who can organise such options) as dynamic demands on transport. These travel demands and travel patterns are today normally captured by surveys and observations on a yearly basis to inform the production of static timetables.

The planning of a journey includes a matching exercise between the total travel demand and the future availability of vehicles to serve that demand and provide the transport service. The matching will be successful only if no disturbances in the traffic process occur and no characteristics of an open-loop control system are evident.

When technical systems such as ITS are put into a societal context, complexity emerges. The systems have to be designed in a cost-effective, efficient, safe and environmentally acceptable way. These objectives require design methods which make it possible to cope with system complexity.

ITS usually involves several human decision makers – and all the decision-making processes which require information about the ITS environment must be considered. Integration of network operations, transport processes and stakeholder perspectives is necessary. Analysis, design and evaluation of this complexity, and its impact on modern solutions for transport services, must be performed adequately.

Activities (or processes) in society which make use of a technical infrastructure and communications networks will be influenced by a large number of decision-makers and stakeholders. They are often geographically dispersed, have contradictory goals and act with different time horizons. In consequence, description and analysis of the interaction between technology and people in a specific class of systems can become so complex that specialist tools and techniques may be required. Expert help should be sought where necessary.

Three highly interrelated perspectives - networks, processes and stakeholders - can be usefully identified and, if combined in an operational way, can be helpful to the analysis, design and evaluation of ITS solutions.

The network perspective is focused on the links, nodes and elements for transport and communications which, when brought together, form the physical network and its structure. The use of technologies (and especially ICT) is important and adds complexity. This can be dealt with by breaking down the network into subnets or subsystems.

The process perspective is focused on the interaction between network components and the different flows of traffic or communications that can be identified in the processes. The dynamic characteristics are related to the transmission and transformation of information and related information channels. A matching between the time horizons of the control processes and the speed of information exchange is crucial for acceptable performance.

The stakeholder perspective is highly related to how ITS supports decision-making. The stakeholders have to interface with the processes and the networks by means of work stations, control panels, mobile or other in-vehicle units. The interface designs must be adapted to the mental models of the processes used by the stakeholders in their tasks. An appropriate filtering of information has to be introduced if the stakeholders are not to be overloaded, or disturbed by other processes or events outside of their control. A hierarchy of abstraction levels can be established. (See Users of ITS and Stakeholders )

Designers often build technical systems without completely understanding the tasks to be performed. Intelligent Transport Systems (ITS) need to be designed to be both useful and usable. Being usable is not enough if the system is not first useful. Users of ITS are diverse individuals – they do not all think the same way and they can be inconsistent and unpredictable. (See Diversity of Users)

It is not surprising that it is often difficult for the designers of technology to understand exactly the real needs of their potential users, how the technology will be used and how use will change as familiarity with the system or service develops. This is particularly the case for complex systems such as ITS in the broader transport context. The goal of good design is for complexity to be made to appear simple or intuitive to its users.

The complexity of ITS processes and their dynamics makes it essential to use sound design principles for robustness. For this reason, ITS require feedback of information from different process states using appropriate sensors. The feedback will also provide the input to adaptive control algorithms for decision-making by users – and make the processes less sensitive to disturbances. The complex nature of transport systems involving the interaction of many different systems and services is clear from the information feedback loops and the varied timescales used in the different decision-making processes.

Human error becomes virtually inevitable with the large number of different links and connections in the networks and processes of modern transport systems. In the transport domain one of the most critical situations is that of driver-vehicle interaction – as mistakes, slips and lapses in the primary driving tasks will have safety implications. (See Human Performance)

As well as reducing critical errors, there are many other practical reasons for involving users:

The overall message is that ITS should not be designed, developed or introduced without involving those who must use it. A holistic approach is required which acknowledges and accounts for the interactions between ITS and its users.

User centred design (UCD) is a well-tried methodology that puts users at the heart of the design process, and is highly recommended for developing ITS products and services that must be simple and straightforward to use. It is a multi-stage problem-solving process whereby designers of ITS analyse how users are likely to use a product or service – but also tests their assumptions through analysing actual user behaviour in the real world.

A key part of UCD is the identification and analysis of users’ needs. These have to be completely and clearly identified (even if they are conflicting) in order to help identify the trade-offs that often need to happen in the design process.

User-centred design (UCD) aims to optimise a product or service around how users can, want, or need to use the product or service – rather than forcing users to change their behaviour in order to meet their needs.

The ISO 9241-210 (2010) standard describes six key principles of UCD:

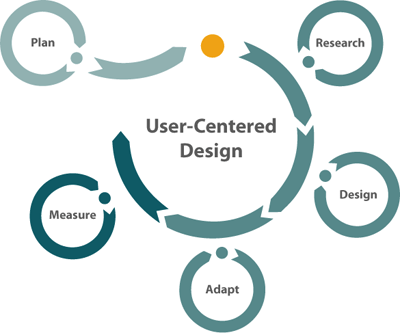

As shown in the figure below the main, but iterative, steps in UCD are Plan, Research, Design, Adapt, and Measure.

Steps in User Centred Design

A key part of the research stage for UCD is collecting and analysing user needs. Quality models such as ISO/IEC 25010 provide a framework for this activity.

Users include the following:

Some important questions related to user needs are:

User needs can also be defined according to the following list of attributes for an ITS:

The main advice is to adopt a user-centred design (UCD) process that begins with collecting and analysing user needs. The design of the ITS product or service can then be undertaken making use of all the advice and guidance provided below. The product or service should then be trialled and developed with actual users, taking account of their feedback. (See Piloting, feedback and monitoring)

Assistance from human factors professionals should be sought where necessary as there are many techniques available to collect user needs. Some of the main techniques include:

Assistance from human factors professionals should be sought where necessary. The following general guidelines are useful in compiling user needs and undertaking analysis for use in ITS design:

Analysis of tasks and errors is a hugely important activity for anyone seeking to understand how users interact with ITS or wishing to create the environment in which the interaction will take place – between users or between a user and an object/activity. Task analysis requires understanding and documenting all aspects of an activity in order to create or understand processes that are effective, practical and useful. Typically a task analysis is used to identify gaps in the knowledge or understanding of a process. Alternatively it may be used to highlight inefficiencies or safety-critical elements. In both cases the task analysis provides a tool with which to perform a secondary function – usually design-related. Error analysis is a specific extension of a task analysis and is about probing the activities identified by the task analysis – to determine how and why a user might make an error, so that the potential error can be designed out or the consequences can be mitigated.

The person conducting a task analysis first has to identify the overall task or activity to be analysed, and then to define the scope of the analysis. For example, it may be that they wish to examine the tasks performed by an operator at a monitoring station, but are only interested in what the operator does when they are seated at an active station. This would be the defined scope of the analysis.

Within this overall activity all the key subtasks that make up the overall activity must be identified. It is up to the person undertaking the analysis to decide what represents a useful and meaningful division of subtasks. This is something that comes partly from experience of performing such analyses and partly from understanding of the activity being analysed. Crucially, each subtask should have a definable start and end point.

With the subtasks created, the investigator then defines a series of rules and conditions which govern how each subtask is performed. For example, it may be that the monitoring station operator has at their workstation a series of monitoring systems (subtasks) where each subtask is distinct and separate – and it may be that the operator must perform the subtasks in a pre-defined sequence. The investigator must specify the rules governing how each subtask relates to the others. For example: “perform subtasks A and B alternately. At any time, perform subtask C – as and when required”.

The investigator would then look at each subtask in turn and perform a similar process to the process described above. The subtasks that make up subtask A would be identified and the rules governing their commission defined. This process of hierarchical subdivision continues until either there is no more meaningful division of tasks that can be performed – or the investigator has reached a level of understanding useful enough to inform the design.

Performing a task analysis allows a researcher to identify the following:

An error analysis builds on the task analysis and requires a similar approach. It looks at all the different ways in which an operator or outside agent could perform an error in each subtask identified. For example, one subtask for the operator of a monitoring station, may be to activate an alert system. Errors could include (among others), selecting the wrong incident response plan, pressing the wrong button, failing to push a lever all the way, looking at the wrong screen or dial, or activating the system at the wrong time. Typically such an analysis would be performed by considering each of a list of possible error mechanisms in turn, to avoid missing potential errors. Again, a combination of experience in conducting error analysis and an understanding of the workings of the overall activity are useful.

Before conducting a task or error analysis it is important to define what the output of the analysis is to be used for, as this will influence how the analysis is performed. For example, it may be that the investigator is only be interested in particular subtasks and activities – or that a particular level of detail is required, below which the analysis is useless and beyond which it is simply a waste of time and effort. Knowing the level of detail required is a key parameter as without this cut-off point, the analysis could go on almost indefinitely. A basic task analysis is a useful way for anyone to gain a clearer picture of any working environment. For more detailed analyses or situations where the task analysis is to provide the foundation for a larger set of activities, it is advisable to acquire the services of experienced practitioners.

The following is a basic overview of the key principles/stages:

break the overall task down into stages:

A task analysis is often useful in its own . It may also be useful to conduct a complimentary error analysis. Again it is best to use an experienced professional for large-scale analyses – but for a basic assessment, the following method can be applied:

Before introducing ITS or any new technology, or undertaking extensive field trials, it is invariably beneficial to pilot the system or service with a small group of users before more widespread deployment. This approach is part of User Centred Design (See User Centred Design) and allows any problems to be addressed, avoiding embarrassing and expensive mistakes.

Encouraging feedback from users and providing suitable mechanisms for monitoring use of ITS allows those responsible for its operation to better understand the experience of both occasional and frequent users. This may show how use of the ITS is changing over time (because of changes in other parts of the transport system or the environment) and provides advanced information about necessary modifications, including possibly re-design of the ITS (See Evaluation)

Even apparently simple tasks such as administering a questionnaire should be piloted. This is because the design of the questionnaire (and the management processes around the questionnaire) may be found deficient or ambiguous when exposed to actual users. Piloting is really important and should not be missed out.

Pilot studies should be well designed with clear objectives, clear plans for collecting and analysing results, and explicit criteria for determining success or failure. Pilot studies should be analysed in the same way as full scale deployments.

In general, the benefits of a pilot study can be identified under four broad headings:

Monitoring the use of ITS can take many forms. Some examples are:

Feedback is information that comes directly from users of ITS about the satisfaction or dissatisfaction they feel with the product or service. Feedback can lead to early identification of problems and to improvements.

When the ITS users are “internal”, such as traffic control room staff or on-site maintenance workers – encouraging feedback has to be addressed as part of the organisational culture. Ideally a “no blame” culture will exist that allows free expression about what works well and does not when ITS is incorporated within wider social and organisational settings. Some industries have an anonymous feedback channel to allow comment on systems and operations. Explicit and overt mechanisms to respond to feedback help encourage further contributions from ITS users.

Feedback from road users about ITS has to be carefully interpreted as it may relate to the wider transport system of which ITS is just the visible part. For example, a complaint about the setting on variable speed limit signs may arise because information about incident clearance is not speedily transmitted to a traffic control centre.

Many organisations publish a service level promise or “customer charter” and this may include feedback mechanisms. Road Operators may choose to implement feedback channels that are passive (such as publishing address/phone/email/web address) or adopt more active mechanisms (such as questionnaires and surveys).

Overall evaluation of ITS products and services is an important activity because the performance of the road user will depend crucially on the usability of the ITS. A benefit of improving the ease and efficiency of ITS technology, is increased user satisfaction. This can provide business advantages, particularly when users have a choice of ITS products or services. Poor usability of ITS, such as a poor user interface, or inadequate and misleading dynamic signage, may have safety implications in the road environment. Good usability will help to manage and predict road user behaviour and so help increase road network performance. For all these reasons, the performance of ITS in terms of its usability needs to be measured. (See Evaluation)

Usability measurement requires assessment of the effectiveness, efficiency and satisfaction with which representative users carry out representative tasks in representative environments. This requires decisions to be made on the following key points:

Steps in performance measurement:

The process of measuring human performance when the driver is interacting with ITS (particularly when using information and communication devices) can yield safety benefits – although there are challenges with this form of human performance measurement in this context.

Driver distraction (not focussing on the road ahead and the driving task) is an important issue for road safety. ITS products, such as information and communication devices, can greatly assist the driver (for example by indicating suitable routes) but ITS can also be an additional source of distraction. Distraction can make drivers less aware of other road users such as pedestrians and road workers and less observant of speed limits and traffic lights. (See Road Safety)

Measuring driving performance when interacting with ITS requires specialist equipment and expertise. Measurements made in laboratory settings and driving simulators may not be representative of real driving behaviour. This is because in real driving contexts drivers can choose when to interact (or not) with devices – and can modify their driving style to compensate to some extent for other demands on their attention. On-road measurements have to be designed to be unobtrusive and representative. Field Operational Tests (FOTs) can be designed accordingly and used to investigate both mature and innovative systems. FOTs can involve both professional and ordinary drivers according to the focus of investigation. A “naturalistic” driving study aims to unobtrusively record driver behaviour. Analysis of the drive record is used to identify safety-related events such as distraction, although the interpretation of results can be problematic and controversial.

The weight of scientific evidence points to distraction being an important safety issue. Many governments and Road Operators have sought to restrict drivers’ use of ITS while driving. There are different national and local approaches ranging from guidelines and advice – to bans on specific activities or functions (such as texting or hand-held phone use).