The deployment of ITS projects requires visionary strategic planning and sound project appraisal. Strategic planning sets the vision and roadmap. (See Strategic Planning) Project appraisal sifts and ranks beneficial projects competing for scarce resources to inform the investment decision. (See Project Appraisal) In a continuous planning and deployment process, an effective approach to implementing project(s) is required to secure best value for money.

It is important to address the factors that underpin the appropriate procurement decision. In other words, having judged that an ITS project represents a sound investment because its benefits are assessed to far outweigh expected costs - how should the project be procured and implemented? This involves:

Funding is defined by the Concise Oxford Dictionary as "a sum of money made available for a particular purpose". It is often confusingly and unhelpfully used interchangeably with financing - which is better defined as "providing funding".

PIARC Technical Committee A2 Financing, Managing and Contracting Road System Investment 2008-2011 clarified by defining "financing" as "provision of the capital to cover the cost of an investment project" whereas "funding" as "provision of financial resources by the public sector, aid donors, users (taxpayers, and toll payers) and/or other beneficiaries for an investment project".

PIARC Terminologies gives the full definitions of funding and financing.

This differentiation is particularly helpful in clarifying stakeholder responsibilities, mapping out cash-flow timings, pinpointing underlying causes of delay or failure in deployment, and developing and progressing a portfolio of beneficial projects that are affordable.

ITS is often deployed as part of a wider road project. An example is MIDAS: the Motorway Incident Detection and Automated Signalling system in English motorways (See www.highways.gov.uk). Increasingly ITS projects are being deployed as freestanding projects, such as Berlin's traffic management centre and the M42 active traffic management scheme (See Active Traffic Management)

Whether as part of a wider road improvement or a freestanding project, there is a multitude of sources for financing the capital works and, to a lesser extent, the subsequent operation and maintenance.

Depending on the economic and financial advancement of a country, the sources of project financing for ITS projects include the following.

Traditionally, very low income countries have attracted grants from multi-lateral institutions, such as the World Bank International Development Agency (IDA), to finance the capital cost of road improvements, with or without ITS.

The European Union provides various grants for ITS deployment to its Member States, some of which are among the richest countries in the world. The European Union also offer grants to Member States to help finance the capital works of ITS projects. These EU grants, which need not be repaid, typically require matching national financing. Some of the EU grants, such as the Cohesion and Regional Development Funds, are targeted at less developed EU regions and Member States. Other EU grants for financing ITS projects include:

Less well known is the opportunity for selected African, Caribbean & Pacific, Central Asian, Asia and Latin American, and EU Eastern Neighbours countries to borrow from the EIB - even though these countries are not member countries. The EIB can lend to these selected countries according to the mandates set by the European Union. (See EIB Regions) Projects with environmental benefits are particularly favoured.

Multi-lateral loans typically involve some form of sovereign guarantee by the borrower's country to repay the principal and interests.

Multi-lateral institutions have long been encouraging member countries to involve the private sector in the provision of infrastructure assets and services. Multi-lateral institutions have also developed private sector lending to projects on a non-recourse basis. The International Finance Corporation, which is part of the World Bank Group, is the most prominent in lending to private sector infrastructure. Other regional institutions are increasingly involved in lending on a non- or limited- recourse basis, for example the African Development Bank and the Asian Development Bank.

In recent years some governments have set up special purpose funds and/or national development banks to co-finance infrastructure projects, including road, involving private sector partners. Examples are:

With the growth in public-private partnership projects in the mid 1990s, some major private sector banks set up in-house PE units to co-invest in the equity of PPP projects. Following the 2007/8 Global Financial Crisis, many of these in-house PE units have been spun off as independent organisations, as they are now considered as non-core assets for the banks.

In the past few years traditional PE managers have started to invest in infrastructure, including ICT and roads. Some PE managers, such as 3i Group plc, Blackstone and KKR & Company LLP , have set up special-purpose infrastructure funds. PE managers typically invest in the equity portion of project finance.

An Infrastructure Fund is the common name for closed-end investment funds, which may be publicly listed and traded or or unlisted. Examples are:

These funds typically invest in the equity portion of the infrastructure projects. Some more recent infrastructure funds are focussed on investing in the debt portion of infrastructure projects. Examples are the GCP Infrastructure Fund Limited and Sequoia Infrastructure Debt S.A. . The rationale for debt focussed infrastructure funds is three fold:

The Global Financial Crisis of 2007/8 triggered a severe squeeze in the availability and price of debt for private sector financing of infrastructure projects. Consequently, the advent of debt infrastructure funds is particularly welcomed.

In recent years some very large pension funds, particularly from Australia and Canada, have been active investors in road infrastructure assets. More recently, an investment platform for UK pension funds to invest in infrastructure has been set up. (See Pensions Infrastructure Platform Limited)

Prior to the Global Financial Crisis it was common practice for a handful of private sector banks to form a syndicate to jointly lend to a major PPP project. Now banks club together as equals to jointly lend to a major project. This means longer bank terms negotiation and slower credit decision-making. All banks have to agree to whatever that is negotiated and agreed. The Global Financial Crisis has weakened the financial strength of many private sector banks involved in PPP infrastructure lending, and has exposed many of the banks' working assumptions as optimistic. Consequently, the availability of this particular source of project financing has reduced and the cost has increased. Recent international regulatory moves (known as Basel III - designed to make private sector banks more robust from failure) require banks to hold more capital against infrastructure lending. This is likely to further increase cost and reduce availability of bank loans for infrastructure projects.

Capital markets have also played important role in infrastructure debt financing in the form of bond financing. One advantage of bond financing over bank loans is the longer tenor. Some bonds come with repayment guarantees underwritten by multi-lateral institutions and/or specialist insurers, known as 'monolines'. A disadvantage of bond financing for projects with a long construction period is 'negative carry' where the cost of financing exceeds the return on the investment. This results from the difference between the interest paid to bond holders and the interest received for the money deposited during the construction period awaiting disbursement.

Multi-lateral institutions offer a range of financial guarantees against various risks, ranging from political and regulatory risks to risk of shortfall in expected revenues. For example, the Inter-American Development Bank guaranteed 10% of the bond issue for the project financing of the Santiago-Valparaiso PPP toll motorway in Chile in 2002.

The Multi-Lateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA) offers political risk guarantee, whereas the World Bank and Asian Development Bank and Inter-American Development Bank offer partial risk guarantees (PRGs) that cover regulatory and revenue risks.

In the mid-1990s the private sector began to offer guarantees for bonds, providing investors with the highest possible rating. These 'triple-A' rated specialist insurance companies provided comprehensive guarantees, known as 'monolines', that were in excess of the PRGs offered by the multi-lateral institutions. The objective was to ensure project implementation and cover timely payments to investors whatever the actual project performance. These monolines have been severely weakened by the Global Financial Crisis. All have lost their triple-A ratings and do not have the same capacity to underwrite financial guarantees as they did prior to the Global Financial Crisis.

ITS projects need to be paid for if services are to be sustainable. Broadly, there are three types of cost that have to be funded:

Unlike project financing, the sources of funding are much more limited. The two principal sources of funding are:

A PIARC Technical Committee reported in 2012 on the taxes and fees paid by motorists in 22 countries. Many, particularly developed countries, have long abolished the hypothecation of revenues raised from motorists. The substantial revenues collected go straight to the general tax pool. Nevertheless, a number of countries, such as Cote d'Ivoire, Madagascar, Russia, Switzerland and United States of America, maintain dedicated funding mechanisms to fund road projects, including ITS.

These are the two primary sources of funds for ITS projects. Some projects have a third source because ITS has the ability to capture a large amount of useful secondary information in addition to the primary function. This allows ITS service providers to add value by re-packaging the information gained to third party stakeholders. For example, the Motorway Incident Detection and Automated Signalling system in England provides journey time reliability data that can be re-packaged into lorry route schedules.

As a source of funding, third party funding should be seen as the 'icing on the cake' and not a primary source. Some ITS suppliers have been caught out by over-optimistic assumptions on a third party funding stream. (See Mixed Results for Public-Private Traffic Management Partnerships)

There is great diversity in the instruments used to fund ITS projects, how they are financed and the models used in the funding schemes. A study for the European Commission identified a number of different arrangements:

The budgetary environment and constraints faced by road authorities and public road network operators today are well known. They are continuously expected to do more with less. Capital and maintenance expenditure is increasingly being rationed or trimmed, and many RNO project deployments are slowed or dropped. As ITS matures and becomes main-stream it may no longer attract any special budget treatment that might be available to a one-off novel ITS project.

The challenging overall budgetary environment, in itself, calls for effective budget planning. ITS systems are typically medium term assets (5-15 years), involving significant operating costs and rapid technology evolution and - consequently - obsolescence. Effective budget planning to confirm project affordability is critical for ITS deployment. This not only promotes good financial stewardship and governance, but also helps to avoid a situation where financing and funding problems are the source of indefinite delays and/or undermine the sustainability of ITS services deployed. In a constrained budgetary environment the importance of getting firm spending commitments into budgets, where competing projects are involved, cannot be overstated.

Budget planning needs to be done at both the individual project and the cumulative programme levels.

The starting point for an ITS project relates to the expected capital costs for start-up and the on-going operation and maintenance expenditures. To this should be added the cost of financing the creation of the ITS asset and the working capital for on-going operations. The timing of these various expenditures should be part of the budget planning process.

Equally important, if not more so, is to plan the funding stream. What, when and from whom will the money to pay back the project investment and operating costs be obtained? This needs to be realistically mapped out. Unless financing for the project can be paid back there can be no project. A project's deployment is all subject to affordability.

Budget planning for a Road Network Operations ITS deployment programme is vital to ensure there is the capacity to deploy a stream of projects with value for money, maximising benefits from synergies among projects. In a fast developing technology business, ITS developers and suppliers are invariably from the private sector. They will focus on markets with continuous and/or growing demand rather than one exhibiting "stop-start" demand syndrome.

The OECD has made recommendations on Budgetary Governance including ten principles that provide an overview of good practices and gives practical guidance for designing, implementing and improving budget systems. (See OECD Principles of Budgetary Governance)

Procurement laws typically dictate how a public authority should go about buying in a project or service, including ITS. For example, in the European Union countries, except in very special circumstances, any procurement exceeding €134,000 for services or €5,186,000 for works is subject to competition. Many public authorities self impose a lower project and service values. For example, the UK Department for Transport normally requires projects and services exceeding £25,000 to be procured competitively (about €29,600).

Competition in procurement is not only good politics - bringing transparency, anti-graft and accountability - but it also yields other project benefits. Competition facilitates market prices and spurs innovation, higher service levels and better value.

As ITS services move from trials and demonstrations to fully operational, competition in procurement should be the default option. There are situations where a "full blown" competition is not warranted. Where an ITS project or service is of a low value the procurement cost, which can be considerable, could far outweigh the benefits from competition. In such cases, when permitted by local procurement laws, procurement through a single source could be more value for money. (See Competition and Procurement)

Sometimes an unsolicited project or service is put forward by a private sector developer to the public authority. This sort of initiative by the private sector is permitted by the public-private partnership laws of some countries, for example Malaysia and South Africa. Such initiatives are dealt with according to procedures which aim to protect both the intellectual property s of the private developer and the public interest.

A difficult issue for road authorities is whether to opt for single or multiple sourcing of the systems, hardware, software and communications for ITS. The issue is particular (but not unique) to large contracts for traffic control and freeway management systems (ATMS), electronic payment systems (EPS), vehicle fleet management systems. It is easier to maintain supplier independence if open architecture and standards, and non-proprietary systems are specified. (See Applying Standards) Strategies that encourage multiple sourcing and price competition will offer protection for the authorities against becoming bound by a single monopoly supplier.

Whether an ITS project is procured through a single source or competitive tender, road authorities and others should be aware that the provision of ITS often lends itself to natural monopolies. This is because of the need to achieve good geographical coverage of the road network and the high initial investment required to provide the basic infrastructure. For example, an exclusive franchise agreement with a single city-wide or regional agent to receive and issue public data has definite attractions but in a market context it may be regarded as anti-competitive. There are advantages for the authorities involved in making exclusive the operation of traffic and traveller information centres since the authority needs only to make an agreement and liaise with a single provider. But exclusivity can also lead to higher costs later as the incumbent exploits single provider position. Other potential suppliers may be weakened and in the worst case go out of business.

There are special considerations that relate to development projects. Central to this is the intellectual property s for the project and how the supplier recovers the cost of ITS system and product development. This is especially an issue when the public sector is the major – and sometimes the only – customer. Furthermore, early customers – the pioneers – may be paying for development work and problem-solving that will benefit later customers, without necessarily being able to share the development costs with these others. Should the pioneers retain at least a share of the intellectual property s to potentially re-coup parts of the development costs?

In these cases, where competitive procurement is to be followed, the road authority should consider whether the ITS project's technical specifications and performance requirements - as well as the contract terms and conditions - are sufficiently well defined to attract bids that are "fit for purpose", affordable and value for money. Where the project is novel or has alternative or variant solutions with different economic outcomes it would be sensible to incorporate an element of negotiation or dialogue with potential suppliers as part of the procurement process, unless restricted by law.

Lastly is the desirability to get small and medium-sized enterprises more involved in development of ITS services to develop local capability and generate local employment. It is notable that French Public-Private Partnership contracts require the private sector concessionaire to set aside 30% of the value of the capital works for local enterprises. (See: Contracts)

The following is a summary of the different approaches that are available to practitioners who are procuring ITS-based systems and services.

Many road authorities keep a list of past and potential suppliers. Some road authorities pre-qualify these potential suppliers. From this supplier list the road authority invites a suitable supplier to discuss and bid for the work required. Once agreement is reached on the work process, deliverables and price the road authority lets the contract to the chosen supplier.

The road authority prepares a request for proposal (RFP) document which is offered to all interested suppliers who wish to submit a tender proposal. The RFP documents will specify:

Upon receiving the tender proposals the road authority will assess them to determine each bidder's technical ability to deliver the services and financial ability to make any requested payments. This is a traditional method of procuring services adopted by road authorities for the delivery of non-complex road construction or maintenance services.

In an open procurement process any supplier can reply to a request for proposal. The information that each supplier is required to provide in the tender submission must be sufficient to enable the road authority to select the preferred service provider. This method is well established in most countries. Usually there are standardised general conditions of contract available and a good body of contract law to assist in managing this type of procurement. Typically bids are submitted using a 'double envelope' system - so that the bidder's technical proposals and financial offer are kept separate. The technical proposals will be assessed prior to opening the financial offers. Only those bidders whose technical proposals are judged to be of sufficient quality will be accepted.

Some countries adopt this procurement method to promote equal opportunity and to reduce graft in public procurement.

More information is available in the PIARC Technical Committee report Financing, Contracting and Managing of Road System Investment.

A variation on the Open Tender method is to require interested suppliers to 'pre-qualify' before they can go on a tender list for the delivery of services. This is a two stage approach:

Pre-qualification typically takes longer to procure the project. It has the benefit of reducing the overall effort required by the service providers to produce the necessary technical and financial information - and by the road authority in assessing it. Pre-qualification also enhances the road authority's confidence that the service providers invited to respond to a RfP will all have previously demonstrated the required skills and financial capacity to undertake the works. It is normal to employ a double envelop system and assess the technical proposals prior to opening the financial offers. Only those bidders whose technical proposals have been judged to be of sufficient quality are accepted.

More information, including a case study on this procurement method, is available in the PIARC Technical Committee report: Financing, Contracting and Managing of Road System Investment .

Some service requirements have become complex and the contractual arrangements, such as franchise and public-private partnership, have involved significant risk transfer to the private sector. The 'Negotiated procedure' was introduced in the European Union to address the procurement of such complex projects.

Clear, absolute pre-definition of technical specifications and contract terms and conditions can become very difficult. In these situations the client (usually this is the road authority) has a view of what it is seeking, but it does not have a detailed specification of the optimum solution. The authority accepts proposals from industry to finalise those details and deliver the services.

In essence the negotiated procedure follows a 4 stage process:

Pre-qualification - this starts with the publication of the contract notice, followed by the issue of the “Request to Participate” documents to interested parties. The private sector's submission will then be used to select the candidates to participate in the next stage, using the selection criteria which have been determined in advance.

Invitation to negotiate (ITN) - this commences with the contracting authority issuing the ITN documents to those who have pre-qualified, including the terms which it intends to negotiate. Bidders are invited to submit proposals for negotiation. Upon receiving the candidates submissions the contracting authority, after examining the proposals, invites the bidders to enter the negotiations.

Negotiation - the negotiation starts with the submission by the bidders of clarification questions about the contents of the tender documents, and their comments on the draft contract. The contracting authority then negotiates equally with all bidders the details of their proposals. Depending on the extent of modifications during the negotiation period, the contracting authority may publish a “Modifications Document” to include in the tender documents in order to ensure full coverage of its requirements. Some bidders may withdraw at this stage.

'Best and Final Offer' - the remaining bidders (all of them pre-qualified) then submit their best and final offers.Following further evaluation the contracting authority names the preferred bidder and finalises the contract award.

More information, including an Austrian case study, on this procurement method can be gained from the PIARC Technical Committee report: Financing, Contracting and Managing of Road System Investment .

Like the Negotiated procedure (see above), Competitive Dialogue procedure follows a staged process. It differs from the negotiated procedure by commencing the dialogue (discussion/negotiation) with bidders at an earlier stage. This allows the contracting authority to start the procurement process with fewer requirement specifications of its own and greater opportunity for bidders to shape the ultimate contract.

The 3-stage process can be summarised as follows:

Contract Notice - the contracting authority publishes a notice containing its needs and requirements and calls for Applications to Participate (Expressions of Interest) from bidders. From the responses received, the contracting authority will select a short-list of bidders to progress to the dialogue stage.

Dialogue - the dialogue is held with each invited bidder and - without "cherry picking" - will cover areas, such as technical aspects, economic aspects (such as prices, costs and revenue) and legal aspects such as treatment of risk, guarantees, or the creation of a legal entity for a limited purpose (special purpose vehicles). The dialogue will progressively reduce the number of solutions being examined and the number of bidders involved, towards the time when the contracting authority will conclude the dialogue and request the remaining bidders submit to their final tenders.

Final Assessment and Award - the contracting authority will undertake its final assessment of the tenders using the initially declared criteria and award the contract to the successful bidder. The contracting authority may seek fine tuning or clarification the final tender submissions, but the additional requested information may not alter the basic features of the tenders.

More information, including a Slovakian case study on this procurement method is available in the PIARC Technical Committee report: Financing, Contracting and Managing of Road System Investment.

The tasks and functions performed by the private sector have evolved over time from the provision of non complex, well defined, well specified and generally low risk services through to complex, minimally defined, minimally specified, high risk services. In many countries private sector providers are responsible for a range of tasks that previously were undertaken by road authorities. In many of these contractual arrangements the private sector operates and accepts risks that were traditionally borne by the road authorities. For example, the project financing of road infrastructure and services are often transferred to the private sector; also bearing the revenue and asset condition risks of projects.

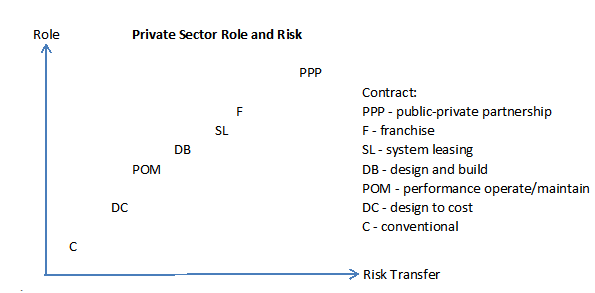

The role of the private sector in the financing, construction, maintenance and operation of road infrastructure and services has evolved. In parallel, the methods used to procure the required works or services have evolved to take account of these developments. (See Procurement and Competition and Procurement) Contract formats have also evolved to facilitate an increasing the role for the private sector, moving the responsibility for and the management of risk from the road authority to the private sector provider. New forms of contract have been developed to clarify roles and responsibilities of each party in order to minimise the risk of project failures, control development costs and secure effective risk management.

The chart below demonstrates the varying role of and risk transfer to the private sector and contract types.

Private Sectore Role and Risk

ITS technology and services are evolving all the time. So too are the road authority and road user needs. (See Business Framework and Road User Needs) Road authorities should be very mindful of possible contract variations during the life of an ITS project, for example in the form of additional service requirements or changes to previously agreed service levels. Invariably, any contract variation - post award - is likely to be costly to the authority. Therefore it is advisable to seek to enter into an ITS contract that has a fair degree of flexibility for contract variation. Very roughly, the degree of flexibility needed for contract variations is inversely proportional to the level of risk that is transferred to the private sector. Road authorities can help themselves by avoiding hasty procurement and spending quality time to define comprehensively the ITS services needed now and during the lifetime of the project, and incorporate the contingent requirements as future options. The contract period should be tailored to no greater than the asset life of the project - this will allow the authority to refresh its needs periodically and take advantage of market competition.

Contract monitoring involves the active recording, assessment and control of all aspects of service delivery during the lifetime of the project. This needs to be specified in the agreement between the road authority and the ITS project contractor. (See Performance Measures) It involves three principal activities:

The methods and procedures for post-award contract monitoring are typically spelt out in the agreement between the authority and the supplier.

The effort required and level of detail involved in contract monitoring will vary at different stages during the lifetime of the contract. There are 3 distinct phases:

The activity of recording the amount, quality and timing of service delivery is increasingly - though not necessarily - carried out by the supplier based on a self-completion quality management system, which will also be specified in the agreement. This is particularly common with contractual arrangements involving a high degree of risk transfer, such as franchising and Public-Private Partnerships (PPP). (See below and link to Public Private Partnerships)

Needless to say, the road authority's contract monitoring team should maintain a good working relationship with the ITS service provider. This hopefully allows the parties to iron out any challenges without involving a third party.

Alternative contract arrangements for road ITS projects are described below.

Conventionally, the contracts used to procure these services have been straight forward, whereby the private contractor is paid an agreed amount to undertake a specified task. The payments will be calculated on the measured amount of works delivered, the period of time the services are being delivered or on the actual costs incurred by the private sector to deliver those services, plus an agreed margin.

Another feature of conventional contractual arrangements is the discreet nature of the works or services, to be provided under separate contracts. For example, ITS system design may be undertaken by personnel employed by the road authority or by consultants engaged by the road authority - under a separate arrangement to that of the construction works. Later operation and maintenance activities when the system is up and running may be the subject of yet another contract.

Under these contractual arrangements, the road authority essentially retains the risks relating to when and how the services are delivered and the levels of service to be provided. It also retains the asset obsolescence risks.

Option 1 is a two-stage approach: the agency issues a request for proposals to a short-list of contractors who have all pre-qualified (in other words, each one has already demonstrated to the agency’s satisfaction that they have the necessary skills and capability to carry out the work.) The total budget available for the project is identified. At Stage 1 each potential contractor is required to submit a detailed proposal covering the methods they will use to meet the contract requirements, the suppliers to be used, and their outline plans for the work. Revisions to this package can be made to reflect common changes that would be required of all suppliers to meet system requirements. Contractors with acceptable proposals then compete at Stage 2 on the basis of costs and other criteria. There is no detailed design work done until after the contract is let.

Option 2 is a one-step selection that is based on the Stage 1 submittals - as above. The contract will require the development of a detailed design document to be agreed by both parties before proceeding with system implementation. Upon approval by both parties, that document becomes the basis for the final contract. If no agreement is reached, the contract is terminated and the payment is based on the agreed expenditure involved in developing the detailed design.

As the complexity of the infrastructure and services being delivered by the private sector increased, many authorities recognised that the supplier of those infrastructure and services may offer better value by undertaking both the design and construction tasks involved. This was seen as a way for the private sector to not "over design" and encourage "fit-for-purpose" designs which may not be onerous to build.

With these contracts, the road authority specifies the general details of the required project. For example, for a road toll system the authority specifies the traffic volumes, number of toll lanes at the toll plaza, the average and maximum transaction times to be incurred by road users. The private sector supplier has the responsibility of designing and constructing the ITS infrastructure to meet those specified details. It is normal for these contract arrangements to require the private sector supplier to warrant the quality and performance of the assets for a significant period, even up to the first maintenance cycle of the asset. In some contracts the same private sector entity that constructed the ITS asset may be retained to also operate and maintain the asset for specified periods of time An example is the accident response system and traffic management centre in Madhya Pradesh, India (See http://mprdc.nic.in/RFQ_for_ARS.pdf ).

A possible downside of employing design and build contracts over a sustained period is that the road authority may lose some of its knowledge on current practice and be less well informed about approaches that may be evolving in the road industry. In contrast, the private sector partner may be more current in its knowledge and be able to increase the benefit of having the designer being in “touch” with the constructor.

Public Centred Operations - in this model, the public agency retains a high degree of control, assumes the major burden of risk and takes on the main financial responsibility for the ITS operation. But even where the responsibility for operations remains firmly in the public sector, there is often a role for private companies in providing specialist support. Out-sourcing of routine ITS support activities, like maintenance of traffic signals and signal controllers, is now well-established in many countries. Other services such as software maintenance and technical support for a traffic control centre may be out-sourced as well. These support contracts can usefully incorporate performance targets, such as minimum response times and performance criteria needed for safe operation (for example traffic signal maintenance at critical intersections). The public sector client will maintain control of the performance targets and carry out performance monitoring in the usual way.

Contracted Operations - a much higher level of delegation is to appoint a private sector company to manage and service the operation, for example, through a facilities management contract. The public agency retains control of operational policy and gives direction but the private company runs the everyday operation and maintains the ITS services. The authority draws up an output specification for the product or service they wish to see developed and invites companies to submit competitive bids to complete this work. Selection is based on the best value for money and quality. The subsequent partnership is pursued on an exclusive basis for the period of the contract. Normally, a “request for partnerships proposal” is used to ensure that the usual public procurement rules of open competition are respected when selecting the preferred partner.

Under the franchise model, management of the entire operation of the ITS service or facility is handed over to the private sector with a very high level of delegation over its development. The public sector agency will specify the terms on which a private company can take on the franchise, but it stands back from day-to-day involvement in the operation. Its role is mainly to see that service standards are maintained and service users are not subjected to unfair pricing. It is normal for the franchise-holder to be appointed after competitive selection. The franchise is usually held on an exclusive basis for a number of years, after which the franchise is usually re-tendered on the basis of an open competition. Franchising opens up the possibility of private capital for the business if there are adequate revenue streams to finance the borrowing. This entrepreneurial approach is seen, for example, in France, Italy, and the USA, where privately operated toll road operators have adopted electronic tolling methods to save on labour costs and reduce the delay for their customers at toll plazas.

Under a franchise arrangement the city or regional transportation authority solicits proposals from potential contractors based on a statement of objectives. Supporting information is requested on the contractor’s capabilities, the resources that are currently available, and the budget that will be required from the public agencies. A franchisee will be selected based on an evaluation of the level of service to be provided, their business plan for future self-support of the operation, the guaranteed levels of information available for free, and the use and timing of public funds. Qualifications and experience will be included in all elements of the evaluation. The maximum time to self-support (typically five years) and maximum franchise period (say, ten years) will be specified. The franchise may confer an entitlement to innovate new revenue-generating services on the back of the basic ITS concession. However, if the business assumptions for the franchise are not sufficiently robust the business will collapse before the franchise has run its full term.

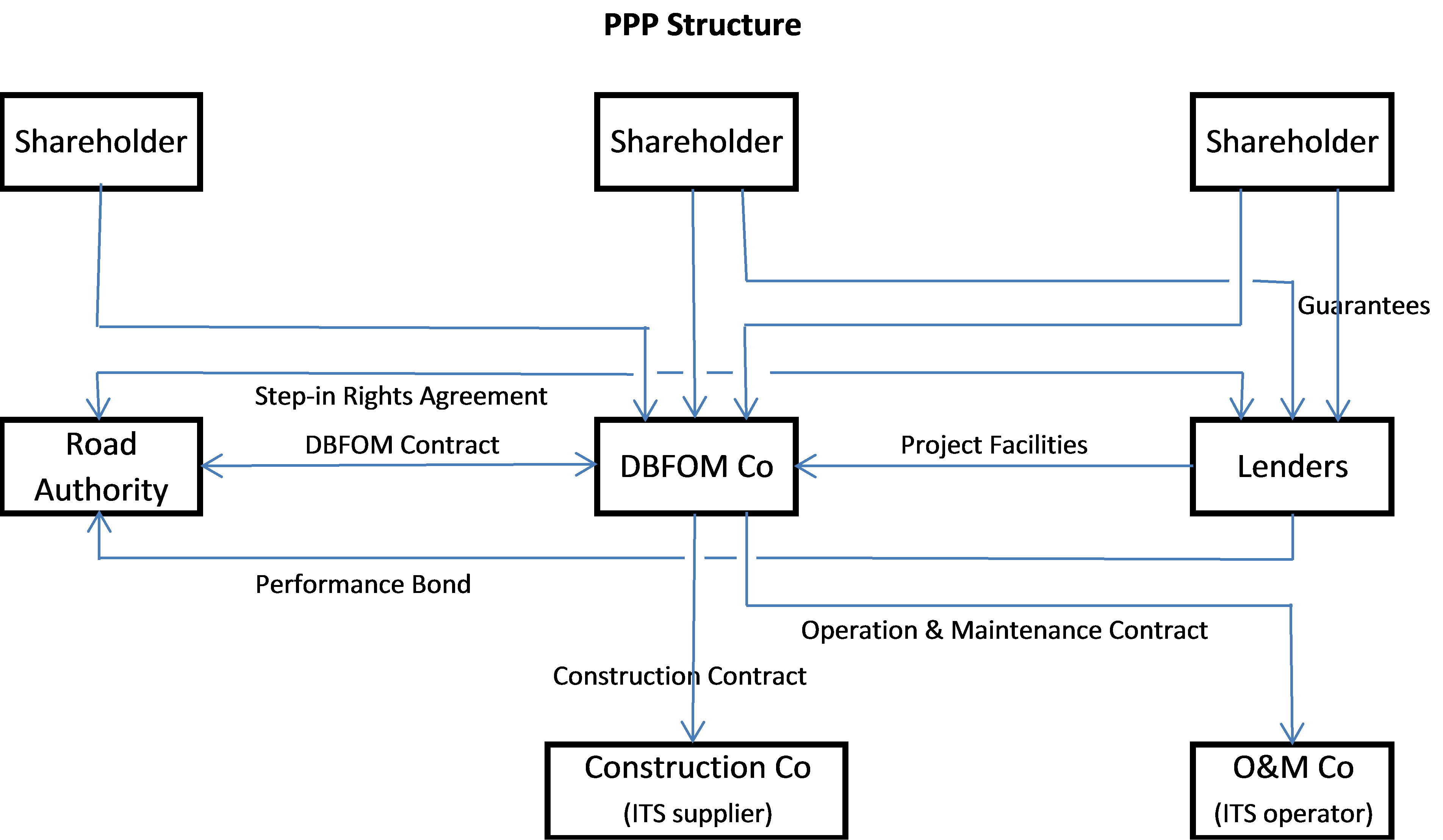

PPP contracts are usually used for large greenfield or significant rebuilding and improvement projects. They typically involve the highest level of private sector participation and risk transfer, including providing the project financing and bearing a level of revenue risk. A typical PPP arrangement will involve tens of contracts and stakeholders because of the numerous responsibilities conferred to the concessionaire. The concessionaire is typically a consortium made up of designers, construction companies and ITS operators and maintenance providers, as well as the equity investors. It can be summarised schematically in the chart below.

PPP Structure

Under a typical PPP arrangement, the road authority determines what ITS infrastructure needs to be built or significantly improved to deliver the required ITS services. It defines its needs (for example the roads and highways to be included, the monitoring sites, the VMS locations) and carries out sufficient preliminary design work to be able to obtain environmental permits and estimate the project’s construction costs. Should land be required the road authority usually acquires it for the project. After a competitive procurement process, a single contract is entered into between the road authority and the private sector partner (often called the concessionaire). The concessionaire has the responsibility to design, build and finance the project according to the road authority’s criteria and then to operate and maintain the road and associated structures, including major maintenance, for an agreed period. In addition, the concessionaire must maintain the ITS asset to meet the hand-back requirements at the end of the concession period. This may require the concessionaire to carry out a remedial improvement programme to meet the hand-back requirements during the last few years of the contract period.

In return for its services, the concessionaire receives payments from the road authority and/or the road users. If permitted by the contract, there may be additional revenue from third-party users of information mined from the ITS system. Although some payments may be made during the construction period, most of the ITS capital costs and all of its operating costs are typically re-paid during the operating period. These payments may be conditional on the availability of the ITS services and the outcomes of a set of performance indicators.

In a PPP contract, significant risks are transferred from the road authority to the concessionaire. Risk transfer in any PPP is very case-specific and can include:

More information on the use PPP contracts, including an Austrian and a Mexican case studies is available the PIARC Technical Committee report Financing, Managing and Contracting of Road System Investment available for download at: http://www.piarc.org/en/publications/search/.