Economic growth generates pressure for society to organise its mobility requirements in more intelligent ways. In the global economy of the 21st century, failure to address inefficiencies in the transport system will have an adverse effect on a country’s competitive position as well as its quality of life. Security concerns are also likely to become more prominent and may impact on transport services and international trade in ways that are unexpected and challenging. The potential for applying greater intelligence in transport is considerable

The concept of intelligence has its origins in psychology. There is no single definition of human intelligence but a variety of viewpoints. One interpretation is that it represents a single general ability to act. Another is a multidimensional cognitive ability that includes reasoning, planning, solving problems, thinking abstractly and comprehending complex ideas. In terms of transport services and products intelligence means ensuring they anticipate and respond to user needs and can be delivered efficiently and effectively - always recognising the diversity of needs and the pressure for compromise and trade-offs.

Several qualities of transport intelligence have been described:

Transport intelligence has relevance to two main categories of stakeholders – the transport operators or “producers” and the transport users. The first group apply their intelligence to construct, maintain and operate transport networks and provide transport services. The second group uses its intelligence to make use of these networks and services for personal and collective travel needs and for the transport of goods.

The needs of these two sets of stakeholders – the producers (which includes road owners and operators) and the users – are often very different and their interrelationships need to be considered when implementing new transport systems. These different requirements are addressed throughout this website( See Measuring Performance).

Any future vision for ITS needs to take account of a number of external factors, the characteristics of systems themselves and the risk of catastrophic failure.

The development of intelligence characterised by these qualities, responsive to stakeholder needs and external factors can be illustrated with the following concepts:

C-ITS Technologies and Applications for Intelligent Transport

ITS Europe (ERTICO), a partnership of around 100 companies and institutions involved in the development, production and deployment of Intelligent Transport Systems (ITS), published in March 2015:

The Report makes recommendations on the roll-out of C-ITS services – in particular, how appropriate use of communication technologies can increase the quality of mobility services, safety and reliability whilst minimising costs. It covers three C-ITS deployment areas – for cities, corridors and traffic management/navigation. It presents relevant existing and maturing communication technologies – and describes their characteristics, cost structures and deployment models. It also maps services to the performance of communication technologies.

The Guide complements the report and is intended as a tutorial or guidance for those who would like a more detailed insight into C-ITS technologies, standards and initiatives.

The Report and the Guide are aimed at policy makers, procurers, operators, service providers and anyone with an interest in ITS. The goal is to support decision making about the most appropriate communication technologies for providing services.

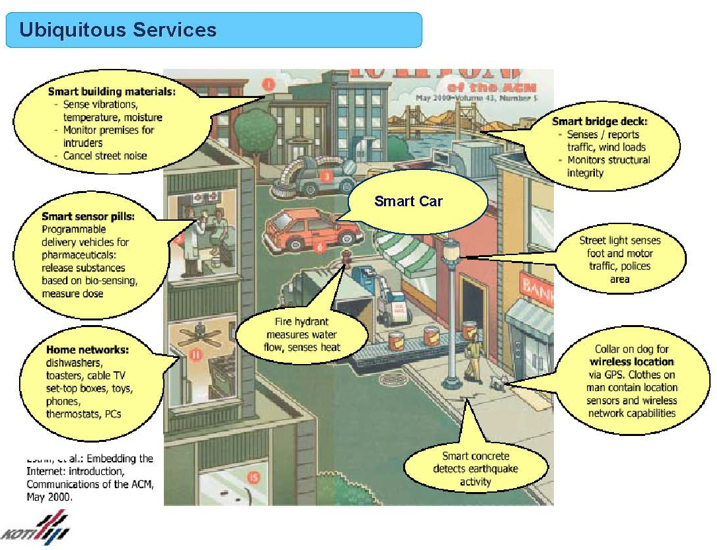

The concept of Ambient Intelligence is relevant to ITS. It builds on the idea that we are surrounded by communications and computer technology embedded in everyday objects such as mobile phones, homes, vehicles and roads. Ambient intelligent systems, services and products are designed to include features that are sensitive and responsive to people’s needs and presence in an intelligent way. Ambient intelligence is fundamental to the concept of ubiquitous services as illustrated in the diagram below by the Korean Transport Institute.

Ubiquitous Services (Source: Korean Transport Institute)

With ambient intelligence comes an expectation of greater user-friendliness, more efficient services support, user-empowerment, and support for human interactions. This means working towards systems and technologies that are not only sensitive, responsive and intelligent but also interconnected, contextualised and transparent. Key enablers are:

Getting the human factors is essential to the successful adoption of new ITS systems (See Human Factors). This requires an understanding of human psychology and what factors influence people’s behaviour. A number of human behaviour issues impact on the roll-out of Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) – and are highly pertinent to the application of ITS:

Political factors in society are also important. New technologies for instance, may become a source of social exclusion. Security, trust and confidence are also potential bottlenecks limiting the deployment of Ambient Intelligence.

Privacy and human s issues are significant. People are distrustful of having their movements monitored or being charged for services without immediate feedback. There may be a trade-off between privacy and service convenience. Some users will expect a degree of control over whether the systems report or conceal their identity and location.

Designers must also anticipate the possibility of hacking, sabotage, vandalism and criminal misuse, and a number of other “worst case scenarios”, not least regular accidental or wilful non-compliance with operating procedures. Self-recognition security systems will incorporate measures for detection, correction, prevention and elimination of these negative aspects. Flexibility to respond “on the fly” in crisis situations should also be written into the design. The consequences of a catastrophic failure must be assessed.

As support systems become more complex, they present the user with the problem of knowing and understanding what the system is currently doing. The driver who misinterprets the action of a complex or automated system may end up “fighting” the system. This is potentially very dangerous. There have been examples of incidents in civil aviation where pilots have tried to take manual control of the aircraft without first disengaging the autopilot.

Another potential problem with complex systems is that it becomes more difficult for a user to determine accurately whether the system functionality is deteriorating and has become substandard. Gradual deterioration combined with rarely used functions may lead to unpleasant surprises and dangerous situations.

When ITS reduces the operator’s role to supervision instead of active control, the supervisory activities can easily be neglected or omitted entirely, to make way for other activities. What can happen is illustrated by research with driving simulators. Drivers readily adapt to the use of anti-collision devices and may rely completely on the device after only a short learning period. If the simulated device is then made to fail, more than half of the drivers tested do not take effective action and crash. These simulations have been made under motorway conditions. A similar level of non-response in urban conditions - with a multitude of moving and stationary obstacles – would be far more dangerous.

What happens in the event of system failure is a critical safety issue. Reliability analysis of systems is essential to be able to deliver good products or services and avoid catastrophic events due to failure of component(s). In communication networks, for instance, it is important to have duplicate circuits, mirror servers and reliable components that are fault-reporting to avoid frequent interruption in communications or unavailability for long periods.

In some cases government agencies have a responsibility to ensure the safety, security and reliability of the system. In the interests of mitigating any risk to traffic safety, the authorities will require computerised traffic control systems to be designed to allow “graceful degradation” from centralised network-wide control to autonomous local control at each intersection. This means that even if a small number of computational and communication units fail, traffic control does not collapse but remains satisfactory. Service can be maintained, although possibly at a slower pace and at reduced capacity.

The consequences of system failure for some of the more futuristic developments - such as automated vehicle platoons – are harder to imagine and will require research.

As towns and cities expand, pressure to rationalise competing priorities for road-space will grow. It will be vital to harness ITS for a variety of transport management measures. In metropolitan areas integrated public transport operations that interface with traffic management systems will become increasingly important. They will provide reliable public transport services as well as reducing the traffic load and environmental burden. The needs of cyclists, pedestrians and other vulnerable road users have also to be considered and integrated. See Safety of Vulnerable Road Users and Vulnerable Road Users

In Road Network Operations ITS helps to improve decision making in real time by transport network controllers and other users – thereby improving the operation of the entire transport system. In future, self-recognition systems will have a part to play in traffic management, travel substitution and “smart” access controls, taking account of the individual characteristics of the vehicle, the load and the journey purpose.

On our highways, better logic, connectivity and knowledge of the spatial requirements is needed for the dynamic allocation of traffic priorities in time and space. This is the case also for journey planning, goods distribution and freight logistics and for demand-responsive collective transport modes. The automated highway or a “smart” intersection will also require a kinaesthetic capability.

Traffic management tools aim to optimise the operation of transport networks in time and space. Although there are clear benefits from “smart” traffic management, it also introduces the risk of gridlock and a “superjam” in the event of system failure, making things much worse. Future systems need to be robust and intelligent enough to deal with worst case scenarios. This is particularly so if the vehicles themselves are automated.

There are other reasons for incorporating more intelligence into integrated road transport and mobility management systems.

First, today’s traffic management and control systems show limitations when facing critical traffic conditions and widespread congestion. This is an almost permanent problem in many metropolitan and urban areas and is often caused by a locally conceived analysis of traffic behavior – when more strategic, high-level control methods, such as demand management, are required. See Demand Management

Secondly, the role of human operators in traffic management centres is still crucial in day-by-day operations. No matter how sophisticated and advanced the traffic control technology is, the “person in the loop” paradigm still prevails today in most centralised traffic control systems. See Human Performance and Traffic Control Centres

Thirdly, the introduction and progressive integration of extended monitoring and management facilities in the new generation of ITS architectures (for example improved road condition monitoring, traffic monitoring, incident detection, collective and individual route guidance systems) has prompted demand for increased, on-line operator support tools. These are to help cope with the complexity of the data to be managed and the resulting, integrated traffic management schemes. See Network Monitoring

Intelligent traffic management systems need to be capable of analysing traffic behaviour and its evolution in a similar way to an expert traffic controller. These systems – for example, self-learning autonomic management systems may replace human operators in the future – and will certainly act as intelligent assistants that cooperate in defining and applying traffic control decisions. Several techniques are being applied in this context including evolutionary algorithms, knowledge-based systems, neural networks and multi-agent systems. See Traffic Management Strategies and System Monitoring

SMART ROADS

“Smart Roads” – an International Road Research Board (IR2B) report from 2013 provides a good example of how to visualise a smart road and what needs to be put in place from a research perspective to produce Smart Roads. The diagram at the end of the report demonstrates that Smart Roads are not just an infrastructure and technical problem – but involve a wide range of issues and interdependencies including societal, economic and environmental challenges, as well as user expectations.

Future dynamic traffic management systems will be required to support network-wide, pro-active traffic management and to replace locally-oriented, reactive traffic management that is common today. Improved intelligence is also needed to deal with the huge amount of real time traffic data generated from detectors and other sources (for example probe vehicles that are equipped to report their position and traffic conditions in real time). The data needs to be interpreted and analysed by the operators to support the decision making process.

Quite how users will embrace and respond to the plethora of emerging new technologies in the transport arena is difficult to forecast. There is a risk of over-dependency with a corresponding loss of skill, and this can be unsettling if systems fail. While choice is often promoted as a desirable objective, many people are overwhelmed by the reality of too many options. See User Centred Design

We need to consider the impact of technology on people, in a world of increasing complexity and change, of seamless near-ubiquitous connectivity, pervasive monitoring and information processing.

What if things slow down because people refuse to take up new technology? Worse, what if a “luddite” mentality takes hold or new under-classes emerge who protest against the systems because they are unable to benefit? Will more bureaucratic control be required in setting rules and protocols to ensure that everything functions smoothly? Transparency in the regulation and certification of these systems may be central to securing public confidence.

ITS is destined to play a key role in vehicles and for travellers using a variety of platforms: smart phones, tablet computers, information kiosks, in-vehicle displays, hand-held or wearable devices. These different platforms offer the potential for real-time information on inter-modal connections and guidance for the traveller to navigate through an unfamiliar interchange. Other developments include navigation for blind and partially sighted pedestrians.

Timely traveller information is now regarded as a key feature for a successful transport system. Today’s transportation consumers must manage their time effectively. Significant uncertainty associated with waiting for a bus or train is unacceptable to most people.

“Smart travellers” expect to have comprehensive information about multiple modes, including traffic information, available to them quickly, in one place or from one source, and on a variety of media. See Traveller Services. Artificial Intelligence techniques have much to offer:

Many consumers are unaware of all of their transport options. The use of personalised information-based technologies can expand traveller choices and facilitate delivery of more convenient services, potentially increasing public transport patronage. Personalisation, if it is to be of value, requires the development of a spatial logic and connectivity that is adapted to the particular user.

Short-term traffic prediction is of great importance to real-time traveller information and route guidance systems. Such systems can only be successful if they are able to convince the driver to change their behaviour. Although traveller information systems have already reached a high technical standard, the reaction of road users to this information and the means of modifying their behaviour is not well explored.

Only relevant information of high quality, provided by a service that is easily accessible, has the potential to change flawed perceptions, for example car-drivers in relation to public transport. The impact on modal shift is likely to be fairly limited unless the whole trip, door-to-door, by public transport is made into a stress-free, seamless experience.

Intelligent navigation systems support individual travellers (usually drivers) by providing information about the shortest possible routes, the actual traffic situation and alternative routes. In combination with context information, near-term prediction and knowledge of personal journey preferences, navigation can become more intelligent.

The effectiveness of navigation systems as a means of relieving congestion is less clear. With widespread use, it is easy to see that congestion is simply transferred to the routes suggested by the guidance system. Route guidance systems as they exist today merely result in spreading the load, temporarily relieving existing capacity problems. Increasingly these systems will have to address the need for dynamic routing depending on information from traffic management centres, connected vehicles and from other travellers (crowdsourcing).

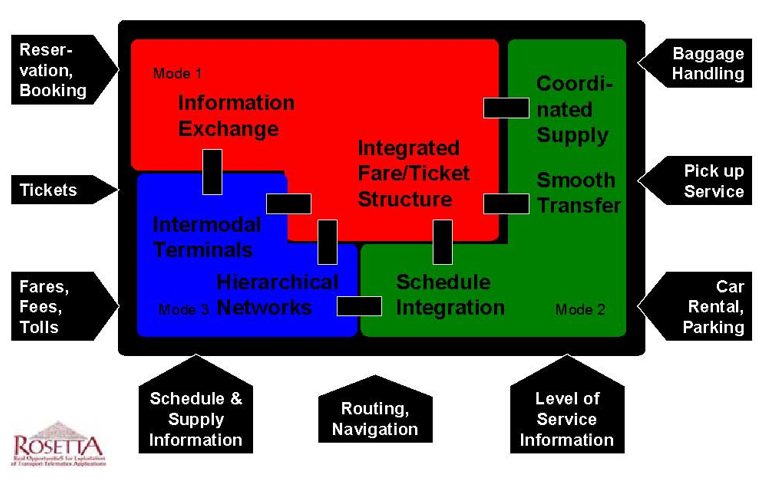

The vision of a smart traveller goes beyond the provision of accurate route guidance and reliable travel information to a vision of a “seamless journey”. As well as the need to move from point A to point B, a number of other services and facilities are used. The mobile Internet has brought about a revolution in how these services are sold and marketed. On-line booking has changed the way we plan our journeys. Travel and other location-based services are being integrated into single packages, but more can be done. The figure below shows a vision for seamless journeys.

Vision for Seamless Journeys (Source: European Commission Rosetta Project, 2003)

On-line, location-based information, concierge (yellow pages), tourist and entertainment services are now widely available - whether the user is on foot, a passenger on public transport, or driving. With an abundance of information available, the need for context- specific and user-specific selection will grow. There will be commercial value in applying successful Artificial Intelligence methods to filter out the unwanted data and capture value and relevance.

The automobile will remain the most important traffic means in everyday life for the foreseeable future. The increase of vehicle safety is therefore one of the most important needs to be addressed by ITS technologies. The distinctive feature will be the awareness of the vehicle, of its environment and its driver’s behaviour. For instance, emulating the diverse functions that drivers perform every day: observing the road, observing the preceding vehicles, steering, accelerating, braking, and deciding when and where to change course.

The push to develop “smart cars” using Artificial Intelligence is part of a wider effort on the part of automotive manufacturers to respond to environmental requirements. Safety technologies already available include traction control, adaptive cruise control, intelligent speed adaptation, collision warning and avoidance systems, driver drowsiness detectors, night and bad weather visions systems, truck roll-over warning systems (See Driver Support).

Critical applications include driver and vehicle surveillance. Accidents are caused by driver inattention or from following the vehicle in front too closely. Ambient Intelligence will offer the opportunity to monitor the driver’s physical condition, diagnose signs of incapability to drive, warn the driver and intelligently influence his behaviour. An important limiting factor may be the reluctance of the driver to accept external control.

In the USA, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) has established an official classification system:

We are on the threshold of the first age of fully automated motoring. The future belongs to innovative driver-assistance technology. See Warning and Control Systems. Sooner or later, these systems will revolutionise active vehicle safety - much in the same spectacular way that electronic stabilisation programs (ESP) have done. Their objective is to prevent accidents using control technology such as an automatic emergency brake assist or the attention control feature that prevents drivers falling asleep at the wheel.

There is some opinion that increasing automation may not necessarily lead to improved safety in the longer term due to effects sometimes described as “risk homeostasis”. This is counterproductive behavioural adaptation when drivers start behaving in riskier ways as a result of a perceived increase in safety provided by ITS (or any other) devices. These effects have not been extensively researched and are often speculative.

Eventually people may prefer automated control to human control in a growing number of situations. However increasing automation raises many issues of risk and investment management. There will be major issues about the rate of deployment of these vehicle control systems once it becomes clear that major reductions in accidents can be achieved using these systems compared with leaving the drivers in control. Testing, responsibility and accountability of intelligent systems are also major issues. Who will guarantee the collective behaviour of multiple vehicles?

The first-generation of vehicle-highway automation envisages automated vehicles operating on existing roads with no extensive infrastructure modifications required. Most of the required intelligence will be built into vehicles rather than the infrastructure. These vehicles will operate at spacings closer than commuter flows of today, with traffic flow benefits achieved through vehicle-cooperative systems as well as vehicle-infrastructure cooperation. See Coordinated Vehicle Highway Systems

Automated vehicles may cluster in 'designated lanes' which are also open to normal vehicles, or may be allowed on high-occupancy vehicle (HOV) lanes to increase their proximity to one another – to realise the benefits of cooperative operations. Stabilisation of traffic flow and modest increases in capacity are seen as the key outcomes.

Once this level of functionality is proven and in broad use, a second generation scenario comes into play which expands to dedicated lanes, presumably desired by a user population with a high percentage of automation-capable vehicles.

With growing use, networks of automated vehicle lanes would develop, offering the high levels of per-lane capacity achievable through close-headway operations where vehicles are closely spaced. However, this type of evolution may take a while. First generation automation for passenger vehicles and trucks is already here, with estimates for second-generation implementation in prospect.

The key technical challenges that remain to be mastered involve software safety, system security, and malfunction management. The non-technical challenges are issues of liability, costs, and perceptions. See Legal and Regulatory Issues, Contracts and Engagement with ITS. It is also important to recognise that automated vehicles are already carrying millions of passengers every day. Many major airports have automated people movers that transfer passengers among terminal buildings. Modern commercial aircraft operate on autopilot for much of the time, and they also land under automatic control at suitably equipped airports on a regular basis.

In the long term it seems unlikely that technological difficulties will hinder the widespread introduction of intelligent vehicles and highway systems. It is more likely to be a sceptical and wary public that is the barrier to acceptance. How will humans cope with increased automation of the driving task? Who wants to share the road with a convoy of 40-tonne driverless lorries? Or are we heading towards the time when human driving will become a form of extreme sport to be allowed only within controlled areas?