An increasing number of vehicle-based solutions that can warn the driver about impending safety risks are installed by automotive manufacturers in new vehicles – and some aftermarket devices are also available.

Infrastructure-based systems, which require communication exchange between the vehicle and roadside to provide warnings, are also being explored. Examples include intersection collision warning and Signal Phase and Timing (SPaT) Warnings. (See New and Emerging Applications and Warning Systems)

Vehicle-based warning systems can help drivers to avoid accidents. Their use in freight and public transport vehicles offers significant safety benefits and has the potential to accelerate more widespread deployment. Legislative options to require their deployment in these vehicles are under consideration.

The USA’s National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) has developed a classification for autonomous vehicles – that scores them on a scale of 0 to 4, depending on their level of automation:

At the simplest level, connected vehicle technologies fall into three major categories:

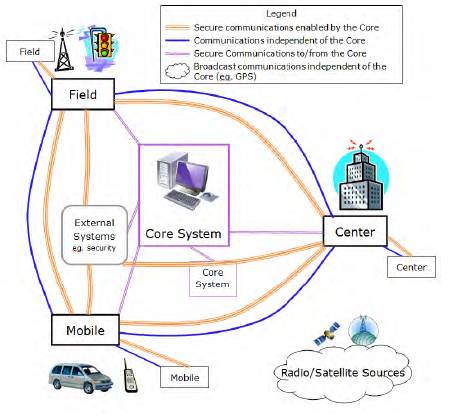

Interactions may take place between any of the components – vehicle to vehicle (“V2V”), and vehicle to infrastructure (“V2I”) – and are standardised to allow any vehicle to link to any other vehicle or to any roadside unit. The figure below is an example of the key syetms, components and their interactions.

US Connected Vehicle Core Systems

The primary focus of connected vehicle technologies has been on short range communications capabilities – which are optimised for very low latency (transmission delay) in support of safety applications.

There is a very broad range of applications which can be built on top of this framework, including – safety solutions such as collision avoidance, mobility solutions such as enhanced traveller information, and eco-solutions such as signal optimisation.

A fully networked transport system may allow much more fine-detailed management of traffic flows. Experimental systems which communicate from the roadside to the vehicle, the recommended speed and acceleration – based on environmental factors such as congestion and roadway geometry –are being tested in Japan under the ITS Green Safety initiative. (See http://www.its-jp.org/english/its-green-safety-showcase/)

The evolution from non-assisted driving to partially automated driving holds challenges that will need to be addressed during the transition to more and more highly automated vehicles:

There are many unknowns about the impact of large numbers of fully automated vehicles on the overall road transport network. While significant benefits are expected, there will also be many operational challenges. It is too early to determine exactly what they will be – and it is anyway likely be some time before such large scale deployment occurs. There is a lot of research being undertaken to understand the issues – with most major automotive manufacturers performing trials, as well as a number of publicly and privately funded initiatives. The availability of highly – and eventually fully – automated vehicles needs to be taken into account by transport planners.

A number of major research projects and programmes such as COMPASS4D are actively investigating Vehicle to Infrastructure (V2I) solutions for warning applications. The COMPASS4D project (http://www.compass4d.eu/) brings together six European cities to deploy three services based on cooperative systems to warn drivers about an incident on the route ahead.

These systems are significantly more complex to implement compared to vehicle-based approaches, as they require deployment of standardised technology on both vehicles and the roadside infrastructure. They show great potential for reducing certain types of road incidents.

There are a variety of functions that this kind of information can enable – such as intersection safety, traffic management and public transport management. Specific applications include signal violation warnings, in-vehicle signal status display, vulnerable road user warnings (for example – pedestrians and cyclists), eco-driving support, and commercial and emergency vehicle support.

Coordinated vehicle highway systems link vehicles to each other and the transport infrastructure via wireless communications – enabling them to share information for improved safety, mobility, and efficiency of operations. Pedestrians, motorcycles, cyclists and other users may also be equipped with handheld or wearable devices which allow them to interact with the system. For example, walking canes enabled with wireless technology to link to customised applications that provide walking directions or warn about obstacles.

These sorts of systems are being developed and tested. A number of technical, financial and organisational, legal and other institutional challenges need to be addressed before they can be deployed on a large scale. Key issues include:

Technologies for safety-critical data capture and communications must be developed to operate at appropriate levels of reliability and interoperability. Systems need to be future proof – able to handle new technology developments and be compatible and interoperable so long as consumer devices and infrastructure remain in service. (See About Standards)

There are security and privacy implications to enabling an unprecedented amount of communication between vehicles (peer to peer) and information sharing across the entire transport network. This requires the development of:

Both the initial deployment and the on-going operation of connected vehicle highway systems must be financed in a sustainable way supported by effective organisational and communication structures between stakeholders – for both field and central office operations. (See Financing ITS and Inter-agency Working)

As with any networked system, connected vehicle programmes are only effective if a sufficiently large number of vehicles participate. To achieve this objective, strategies to accelerate their deployment in consumer and commercial vehicle fleets will need to be developed. They may include some sort of incentive scheme or mandating their deployment.

Partially automated solutions are no longer experimental. In fact, they have proven so effective that they are being mandated in many locations. Vehicle automation is now able to handle increasingly complex tasks – such as parking. It is expected that this situation will continue to evolve, with more and more functionality becoming available to drivers over time.

For public transport – such as guided buses – precision docking solutions using optical or magnetic sensors can improve passenger safety and the efficiency of boarding and disembarking. This can help to reduce overall travel times. Systems have been deployed in France, the Netherlands, and the USA.

Vehicle automation has made major advances over recent years. Many public and private sector research programmes worldwide have now successfully demonstrated that test vehicles can operate without driver intervention for thousands of miles on public highways and within cities. A Tri-lateral Working Group on Automation in Road Transportation (Japan, Europe, US) has been established to progress work in these programmes.

The legality of operating automated vehicles on public roadways has become an issue as more and more manufacturers want to test and commercialise them. Some countries and regions have put in place regulations that legalise these operations. Others are actively reviewing this issue.

There are major social, cultural and legal issues to resolve before a fully automated vehicle fleet can become a reality. For instance – how much control will the majority of drivers be prepared to concede? Who is liable if a system fails? At what stage should automated systems be made compulsory? (See Automated Highways and Liability)

Today’s automated vehicles rely on an array of complex advanced technologies. Examples of basic elements include:

Fully automated driving is rapidly moving from research to real-life deployment. A number of car manufacturers have announced that they will have substantially automated vehicles available for purchase by 2020 – although it is generally anticipated that drivers will still need to be prepared to take an active role in some situations. In the meantime, increasingly sophisticated partially automated systems continue to make their way into the marketplace.

Similar advances have been made in automating vehicle functionality in commercial freight fleets. Work is underway to develop “platooning” solutions, which allow trucks to travel together in tightly spaced groupings to increase the density of freight traffic without prejudicing safety. It also has the advantage of providing fuel economy benefits – in the range of 10% or more for the follower vehicle depending on the gap. Platooning research has a long history, and it continues to advance with recent demonstrations in Japan, Germany, Sweden, and the U.S. (See Case Study on Safe Road trains for the Environment (SARTRE))