Traditional planning processes in roads and highways authorities have focused on capital improvements to roadways. In many countries there were few mechanisms to effectively support ways of improving road network operations or to support thinking beyond the physical construction of facilities and infrastructure. This is changing to allow consideration of how road and highway facilities can operate most effectively.

Planning for operations is inevitably part of the long-term planning effort, but the planning process needs to be more than simply planning for, and funding of, the installation of additional infrastructure. Specifically, planning for operations should ensure a long-term, adequate and reliable source of funds for day-to-day traffic operations and maintenance of the ITS infrastructure.

Planning for Road Network Operations (RNO) now normally includes three important aspects:

Linking together planning and operations will encourage an improvement in transport decision-making and the overall effectiveness of transport systems. Coordination between the planners and operating units helps ensure that regional transport investment decisions take account of the available operational strategies that can support regional goals and objectives.

In summary, the success of RNO is closely related to the strategic role and objectives of the transport agencies responsible for RNO – such as:

These “high-level” concepts should guide agencies in their formulation of policy and operational practices. (See Traffic Management and Demand Management)

Planning for Road Network Operations involves consideration of the organisational requirements for the operational activities including preventive actions. Practical constraints (such as inter-agency demarcations) and on-going local factors must be defined together with the supporting information systems and decision-making or control systems that are needed. The success of a plan depends on the distribution of activities between partners and on their full knowledge and understanding of their assigned tasks.

Generally, design procedures require the following:

The lead organisation for traffic management on the network will need a reliable database for preparing, organising, implementing, managing and assessing operations more effectively. This will enable the organisation to become a valuable resource for addressing ad hoc issues concerning the network, the need for studies and for providing statistical material for publications. (See Data Management and Archiving)

Data includes:

This data will be supplemented with:

The tools needed to establish the database are:

The network management database is not static: there will be a continual, on-going requirement for up-dates.

Maintenance of the data files is a meticulous, time-consuming process that demands specific training to achieve the results required. Theoretical knowledge of the network and its environment must be supplemented with hands-on experience and local knowledge. For example, to determine whether a planned detour is realistic, it is necessary to know as accurately as possible the level of traffic on each road segment. Lessons learnt from the analysis and response of actual situations must be factored into establishing response procedures for future events.

The purpose of an events database is to forecast periods when the probability of traffic disruption is high. The task consists of studying the calendar (dates of public holidays, school holidays and major planned sporting, cultural and entertainment events) and comparing it with previous years, comparable past situations and/or weather forecasts.

Implementation involves specific stages:

The task requires painstaking attention to detail in collecting and analysing data, particularly keeping logs. It is vital work and helps improve the management of the road network – thereby decreasing the number of unplanned incident and emergency response situations.

The purpose of a procedures manual is to define the operating actions of all roadway partners and guide their implementation. A procedure manual consists of listing all tasks to be performed and all resources required to carry out the task specified for each event or incident scenario. Procedure manuals can be produced for roadworks, mobile traffic patrols, traffic monitoring and traffic management plans. The production of procedure manuals is a good subject for initiating and fostering cooperation with partners.

The events to be handled and their consequences will sometimes differ slightly from the scenarios studied. Although procedure manuals need to be detailed, they can and should leave room for some initiative by those at whom they are aimed.

Since procedures manuals are tools common to many partners, it is important to ensure that the reference framework and vocabulary are understood by all. The design of manuals that link to various plans – must be consistent and support cross-referencing. They must be periodically updated and the updates to all documents must be distributed. The provision of procedure manuals on-line may be the best way of keeping them current and available.

There is a twofold objective in tracking the performance of the operating measures:

Monitoring methods must be developed to quantify the impact of the measures implemented and detect dysfunctions or serious variance from anticipated results.

This approach relies on information gathering that must be a systematic and a planned part of routine documenting procedure (logs, fact sheets and other reports).

A small number of basic performance indicators must be defined case-by-case and changes tracked over time. To define these indicators without overlooking key points, the following factors can serve as a guide:

The purpose of updating the operating procedures is to plan for, and justify, the resources appropriate to the context. Resources can include hardware, software and documents as well as personnel organisation and training. The context will cover the traffic situation, incident response infrastructure, organisation of other services, user needs and available technologies.

Updating procedures and operating methods extend to physical assets as well as documentation and service organisation. It specifically requires:

This work requires effort that is rarely spontaneous – and ultimately may highlight needs for specific resources (studies and production of documents). The outcome may be elimination of unnecessary or out-dated working methods. It is also fairly common for objectives and strategies that are initially defined – to be revised in light of experience gained.

A Traffic Management Plan (TMP) provides for the allocation of traffic control and information measures in response to a specific, pre-defined traffic scenario – such as the management of peak holiday traffic or the closure of strategic route because of bad weather, maintenance or a serious road accident. The objective is to anticipate the arrangements for controlling and guiding traffic flows in real-time and for informing road-users about the traffic situation in a consistent and timely way.

The plans, which will differ in detail according to local circumstances, apply in the following cases:

TMPs do not solve all traffic problems but lessen the consequences. They improve coordination and cooperation between partners and facilitate the establishment of mutual agreements on the operational requirements.

A TMP will optimise the use of existing traffic infrastructure capacity in response to a given situation and provide a platform for a cross-regional and cross-border seamless service that provides consistent information for the road user. The situations covered can be unforeseeable (incidents, accidents) or predictable (recurrent or non-recurrent events). The measures are always applied on a temporary basis – although “temporary” may be lengthy, such as a construction or long-term maintenance activity.

TMPs define and formalise:

The purpose of this approach is to limit the effects of events that can lead to serious deterioration of traffic conditions and to enhance road safety. The objective is coordinated action by the various authorities and services that participate in the operation of the roadway.

TMPs can be developed for corridors and networks with the aim of delivering effective traffic control, route guidance and information measures to the road user. An improvement in overall performance is possible by securing effective collaboration and coordination between the organisations directly involved. By strengthening cooperation and mutual understanding a more integrated approach will be achieved to the development, deployment and quality control of traffic management measures. (See TCC Functions, Urban Operations and Highway Operations )

Four geographic levels can be considered for the elaboration of Traffic Management Plans:

Multiple level TMPs, if properly developed, will provide for various traffic situations in a timely and effective manner.

The implementation of TMPs eases roadway disruptions even if the initial event and its consequences are slightly different from the scenarios adopted for the TMP. When a TMP is put into practice the introduction of measures not included in the plan can be initiated by the operator – provided that the new measures are consistent with the spirit of the plan, after agreement with the coordinating authority. Common terminology and an agreed referencing system for key locations are essential for all stakeholders to understand each other clearly. It is essential that everyone has access to the most up-to-date version of the TMP, making version control very important. The wide distribution of TMP documents can lead to different parties working to different versions but this can be avoided if the current versions are held on-line in a virtual library.

TMPs are produced from historic analysis and a consideration of potential operating measures and agreements between all future partners and stakeholders. After a TMP has been activated and the situation returns to normal, feedback from the experience will help improve the effectiveness or performance of future activations.

The objective of systematic feedback – often called “after-action” analysis – is to enhance the effectiveness of an operating plan or action and optimise use of resources. Past situations are used to review organisational factors, event planning procedures and detailed incident response plans.

To secure feedback to the required level the following measures are recommended:

Organising and using feedback is especially important where the operational plan or measure implemented has not previously been applied in a wide-scale exercise or test.

A survey of all planned roadworks will provide important data for the Traffic Control Centre to assess the duration and the time-line of forecast obstructions and develop the least disruptive master plan. This task requires control centre operator awareness and proficient scheduling.

There are some drawbacks and constraints - such as:

The objective will be to schedule roadworks to minimise their impact and reduce disruption to road users, for example by avoiding:

The goal is to minimise the actual or probable disruption to users caused by major construction works by initiating consideration of:

The optimum plan for roadworks operations can be developed by progressively focusing on the best approach for executing the roadworks, incorporating safety concerns and traffic flows, and integrating these considerations and the results into the plan.

This requires knowledge of:

Sometimes several solutions will be available (local detour, alternative routes, alternating open lanes). The choice will be based on total cost, including the cost of work and cost of delays. While work is in progress it is important to check compliance of signalling and operating methods with the content of the operations plan.

A Traffic Incident Management (TIM) team drawn from the leading organisations involved in responding to traffic incidents is useful in many situations. The team can operate as a unit to create the required contingency plans and the related Concepts of Operations (ConOps) – that identify stakeholders and their respective roles and responsibilities in incident management. (See Traffic Management Plans)

An Incident Management Team can be a continuing mechanism for practicing the essential “4-Cs’ of incident management – Communication, Cooperation, Coordination and Consensus – sharing new techniques, training and conducting post-incident assessments. This is done through regular, on-going meetings, perhaps monthly or bi-monthly.

There should be a core group that participates regularly in the continuing activities of the team. Usually this would include:

If there is a TCC in the region, it will be a core TIM member as well. The TCC may take the lead in forming the TIM Team. Other members would participate as needed. (See Table below)

To start a TIM Team, there needs to be a lead organisation or champion to bring together the various parties to create consensus on goals and objectives. In addition there will be logistics to consider (including meeting facilities), which include:

It is generally best if the TIM team champion comes from a public-safety agency, perhaps law enforcement, to encourage colleagues in other public-safety agencies to participate actively.

Effective strategies include promoting the adoption of an “Open Roads Policy” that sets a goal to clear the roadway and open the lanes to traffic as quickly as possible, for example within 90 minutes of the arrival of the first responder (the first official to respond to the scene and render assistance, such as a the police or a safety service patrol).

Some agencies’ delivery of the Open Roads Policy includes the local police and fire rescue departments and the Coroner/Medical Examiner’s Office. The Coroner’s involvement is helpful since it can grant authority to responders to remove fatalities from the roadway providing certain conditions are met (such as taking digital photographs). This avoids any delays in clearing the roadway, arising from having to wait for the Coroner to arrive and direct the removal.

In the USA members of the TIM Team are drawn from a wide range of stakeholders. Some, such as national agencies, serve more in an advisory role than an active role. Some localities also have a regional TIM Team to provide broad-based, and standardised training, and information sharing. An example is the Traffic Incident Management Enhancement (TIME) Task Force in the greater Atlanta, Georgia, USA.

|

Category |

Stakeholder |

|

National Agencies |

|

|

Regional Agencies |

Regional Department of Transportation (DOT) including as a minimum the following departments:

Sometimes the DOTs for adjacent regions are included:

|

|

Local Agencies

|

|

|

Authorities |

|

|

Private Partners

|

|

|

Associations |

|

|

Other |

|

Traffic incidents occur all the time. Events that are more serious in nature are commonly referred to as “emergency events”. Emergency Management brings together different stakeholders to respond to, and manage, emergency events.

Emergency events include events of which there is little or no advance notice – and known events for which the impacts are largely unpredictable – such as a hurricane/typhoon/cyclone. (See Security Threats)

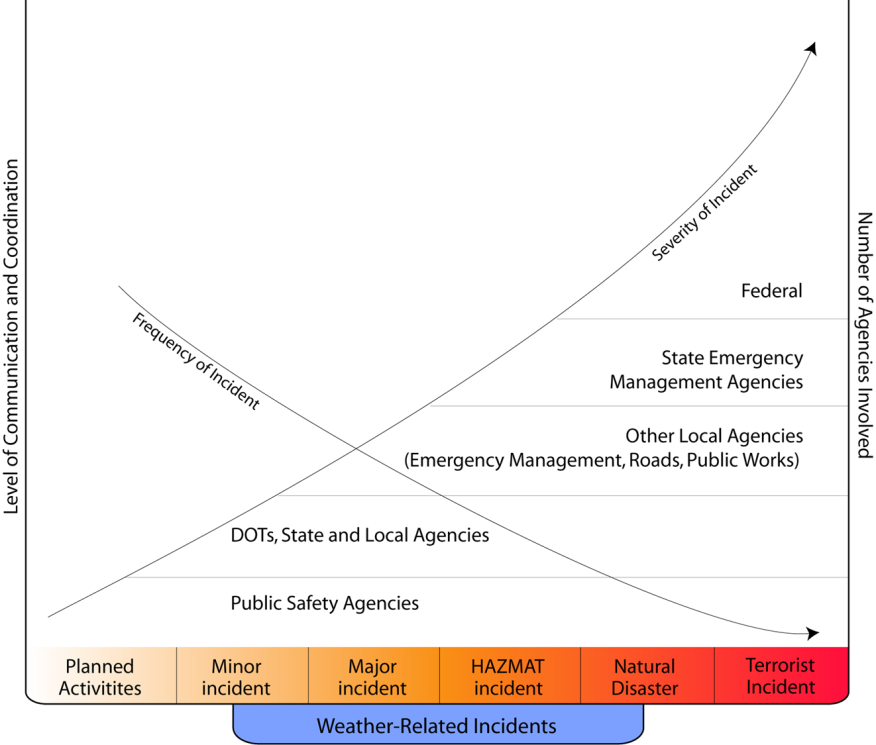

The scope or severity, of incidents is a continuum along which the responders and managers change and the team expands according to the severity of the event. The diagram below illustrates this continuum. Whatever the severity, first-line responders generally include law enforcement, fire rescue, emergency medical services, vehicle breakdown and recovery teams – and in the transport community, the road authority’s maintenance teams and mobile Safety Service Patrols. The TCC will be involved throughout as well. The involvement of agencies providing oversight and support will change as the severity increases – to include other stakeholders such as emergency managers, state and even national agencies. (See Incident Response Planning)

Normal practice is to designate an Emergency Coordination Centre from amongst the first-line responders. Often the Traffic Control Centre is well-placed to take this role. Where possible, the demarcation and allocation of responsibility for public statements, policies on the use of social media and press briefing – for different kinds of emergency, needs to be worked out in advance between those with a close interest.

Complexity of different types of Emergency Operations

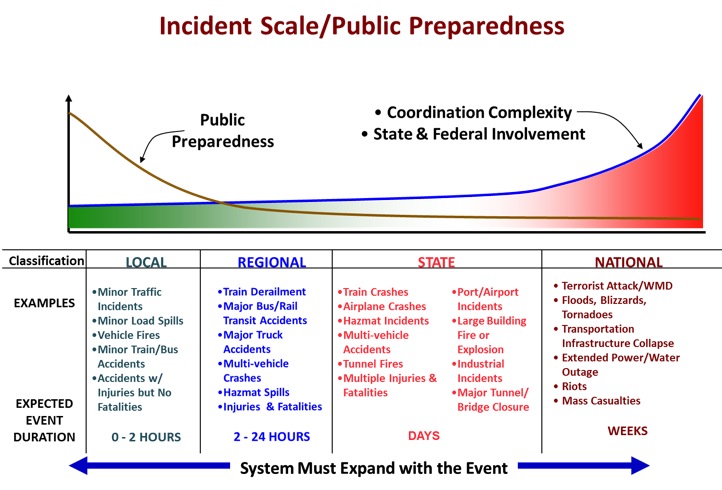

A meaningful way to view this is to consider the degree of public preparedness for the levels of incidents compared with state and national preparedness. Typical types of incident for different levels of severity are shown in the Figure below. The term “incident” applies to all levels of severity but the agencies involved and extent of their response varies and increases from the side to the .

Classification of Incidents based on Coodination Complexity and Level of Public Preparedness

The task of planning for major emergencies - the Regional/ State/National events shown in the diagram above – can be broken down into different stages:

During an emergency situation the Coordination Centre or other lead organisation has various important tasks to perform:

After the emergency has passed it is important to obtain feedback on the experience and information on any operational difficulties in order to update incident response plans:

At the national level in the USA, Federal Highways Agency has brought Emergency Management to the forefront through its Emergency Transport Operations (ETO) Programme. (See http://www.ops.fhwa.dot.gov/eto_tim_pse/index.htm)

All incidents in the USA even minor traffic collisions are subject to National Incident Management System (NIMS) procedures – albeit usually on an informal basis. (See http://www.fema.gov/national-incident-management-system)

The need for Performance Measures in Road Network Operations (RNO) is widely recognised. They have been a topic of discussion for many years but it is only recently that ITS devices provided the data necessary to support performance measures and their importance in RNO. (See Performance Indicators)

ITS can play a major role in performance measurement and will be useful to countries that do not already have strong road network performance management programmes. Performance management is important to ensure that:

Possible categories of performance measures relevant to RNO include:

A USDOT scanning tour of four European nations (England, Germany, Sweden and the Netherlands) in 2005 found a strong interest in performance-based Traffic Incident Management. Performance measures are applied in various ways, to monitor:

The following are being considered for the USA: