Intelligent Transport Systems (ITS) are not deployed in a vacuum but in an environment governed by legal and regulatory frameworks at the local, national, regional and international level. The reach and impact of individual ITS deployments needs to be considered within the context of these frameworks – so that the relevant authorities can put in place appropriate policies and measures to govern the way in which the deployment is managed.

These policies and regulatory measures are made to provide clarity on roles and responsibilities, the legitimacy of ITS deployments, their part in law enforcement and the redress procedures available against fraud, unreliability and misuse.

To ensure trust and public acceptability of ITS deployments in road network operations or transport services – public and private agencies must ensure that their policies address legal and regulatory issues and are seen to be relevant, transparent and robust.

It is comparatively rare for stand-alone legislation or regulations to be introduced in support of specific ITS deployments, although this situation may change in response to new technological challenges such as the automated driverless systems now being developed commercially. Most ITS applications introduced over the last two to three decades have been deployed within existing legal and contractual frameworks that are nevertheless constantly evolving to take account of new developments and practices. Examples include the use of contactless cards for public transport fare payment or electronic tags in drive-through tolling.

The context for ITS deployment will vary from place to place. It is likely that there will be, as a minimum, regulations covering areas such as road safety, consumer protection, contractual liability and commercial competition. In many countries there will also be a body of law and regulation that specifically addresses transport operations. Whatever the framework, it needs to be taken into account when introducing or extending ITS applications. (See Case Study: EU Secure Lorry Parking)

Legal and regulatory issues associated with ITS deployments are an integral part of any deployment strategy. (See Strategic Planning) This is the case whether the deployment is related to the planning and delivery of transport operations and services or to the market introduction of ITS products, systems and services. Common factors that need to be addressed include:

In some countries other factors may come into play – such as social, environmental and economic policy objectives and how they impact on transport and mobility.

It is important to consider the legal and regulatory context at the very start of the ITS implementation, preferably after the desired outcomes have been established – and before any decisions have been taken on how to achieve them. This will avoid unnecessary costly and time-consuming work. Some general guidance regarding privacy and liability issues as they affect Road Network Operations are available at: Privacy and Liability

The design and procurement of the ITS implementation is likely to involve internationally binding, formal and informal technical standards in addition to national or international laws, regulations, procedures and practices regarding public sector procurement. (See ITS Standards and Procurement)

The nature of ITS deployments often involves partnership working with a wide range of stakeholders drawn from the public and private sectors. This can raise a number of significant legal, regulatory, organisational and contractual issues that have to be resolved. It is important for the different partners to communicate clearly with one another and establish a common understanding. The effort that this will take should not be underestimated. It is likely to involve liaising with legal experts, government departments, technology specialists, national standards institutes (See ITS Standards), the telecommunications authority, and others.

By way of example, a local authority may decide to try to encourage bus travel by adding a rewards scheme to a smartcard ticket – but if it does this for one bus operator and not for its competitors, it may be challenged under public expenditure regulation or competition law. These types of issues need to be addressed during the planning stage, not when excluded bus operators take legal action against the local authority and the bus operator.

It is quite possible that there will be earlier examples of technology implementations from which lessons of national relevance can be drawn, even if these are not in the ITS area. For instance, established national legal principles of how banks must deal with their customers’ purchase and location records, is of interest when implementing a smartcard public transport ticketing system and considering how to handle resulting customer and trip data.

Once it has been determined where legal issues come into play during an ITS implementation – whether at the beginning, during, or throughout the implementation and its operational life – it is useful to think in terms of a set of questions to address within the national context.

As with any other branch of information technology, ITS has seen an explosion in the capacity to generate, process and store data over the last decade or two, which will continue using what is nowadays “normal” computing capacity. Large volumes of data can be easily captured, collected, and stored in real-time and processed in a variety of ways. ITS applications draw on a wide range of data sources including details of vehicles, personal details of drivers and public transport users, bank details for electronic payment (tolls, tickets or a congestion charge), origin and destination of journeys, vehicle and personal location.

Data processing and data privacy legislation is constantly evolving to keep a balance between what the national authority and the general public consider desirable and reasonable in handling an individual’s or organisation’s data (the subject’s data). The principles of contract law and privacy legislation apply equally to ITS as they do to any other area of life. Ignoring these principles creates a risk that the ITS application will become a point of friction between authorities and the public. The challenge is to bear this in mind, even where the information appears at first sight to be non-sensitive.

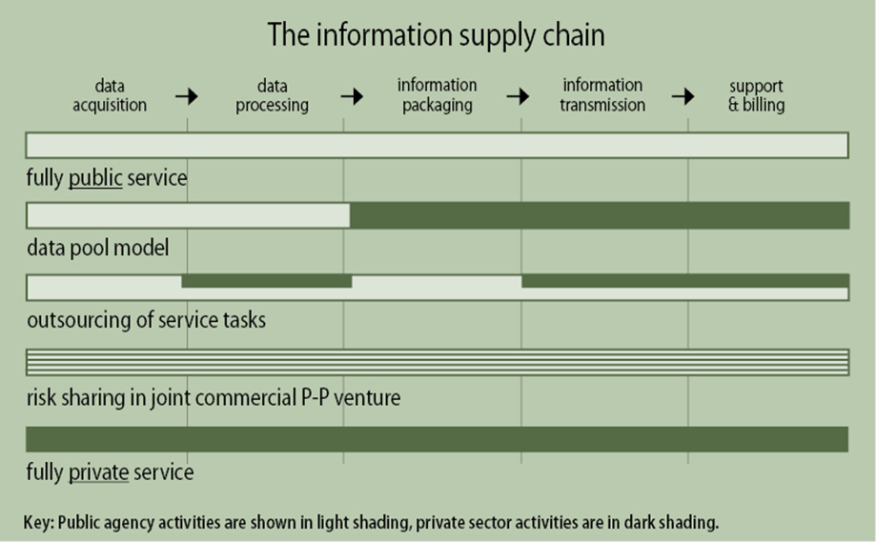

ITS applications cannot function without systematic capture and processing of data. The legal and organisational arrangements involved may be quite complex for even simple applications – such as real-time arrivals at a bus stop. In the case of ITS-based information services the flow of data and content can be organised between the public and private sectors in different ways – as shown in the figure below. The development and delivery of the information service to the end user depends on partnerships and contracts – from data acquisition through to service support and billing. Each of the parties involved will be subject to contract law and enforcement. (See Case Study: Data Sharing, New Zealand)

The information supply chain (Copy PIARC)

Data explosion is not an ITS phenomenon. It mirrors what is going on in social media, on the Internet, in marketing and other sectors. As a result, many countries have legislation and regulation governing how to data should be collected and handled. The ITS sector operates within these frameworks. As with all national legislation, they vary from country to country – but some broad and simple principles apply universally and should be taken into account by ITS practitioners even if there is no relevant legislation in place as yet.

The tension in this area is created by the basic question of who controls the data:

There is often anxiety amongst the general public (who are often data subjects) about what exactly is being recorded, how personalised it is, to what use it is being put, and for how long it will be stored. This concern is not always logical. For instance mobile telephone records and electronic banking systems create a comprehensive, maybe intrusive, data picture of individuals – but mobile phones and bank cards do not often receive the same level of criticism as the identification of vehicles through Automatic Number Plate Recognition (ANPR) (See ITS Technologies) for the purposes of:

The creation, use and storage of transport data – as with any other data – is a sensitive area and ITS practitioners should make sure they remain within the laws and regulations governing data processing in the country in which they operate.

It is sound practice to only collect what you need, restrict this to data actually required for the work to be done – and to discard the data once its purpose has been fulfilled. For example, for the purposes of calculating journey times – it is not necessary to record the names and dates of birth of drivers.

The Stockholm Congestion Tax back office permanently deletes all vehicles and journey data once the journey has been paid for or any dispute relating to the journey has been resolved. Since this office generates tax bills monthly, hardly any data is kept for longer than a month. This is an example of good practice. (See Case Study: Stockholm Congestion Tax)

Restricting types of data, encrypting data irreversibly, and having strict rules for data handling and storage, including time limitations, will keep an ITS application within the bounds of good data practice.

Data should only be personalised when it needs to be. Data collected for tolling (See Electronic Payment or Law Enforcement) purposes has to be personalised to be useable – but even with tolling this can be minimised. For example, the collection of personal data (such as exact trip location) for tolling can be minimised by using a “thick client” – where most of the transaction processing is done within the vehicle – reducing the amount of information sent to the back office to generate the toll charge. When collecting data to establish traffic flows (See Network Monitoring) or public transport usage loading (See Passenger Transport), the names and addresses of travellers are of no importance and should not be collected, even though the possibility exists.

It is a generally recognised principle that information should not be recorded just because it exists and can be recorded. It should only be recorded if it is needed for the process being carried out. For example, vehicle speed data collected on motorways to determine traffic flows – the licence or number-plate data would usually be encrypted in an irreversible way – so that all the data processor knows is that the same vehicle passed point A at x time and point B at y time. Even if the operator wished to reverse the encryption process and identify an individual vehicle, this is not possible.

Data should only be stored for as long as needed. “The to be forgotten” is a phrase sometimes used to express this. Once the process for which data was collected has been carried out – whether this is to generate a toll charge or to authorise a public transport passenger to undertake a journey – it should be discarded. If there is good reason to keep it – for instance, to carry out some kind of statistical analysis or forecasting – it should be irreversibly made anonymous before storage.

Data subjects should be able to check on the personal data held relating to them, and there should be a process for challenging – either the content of the data or the fact it is being stored at all.

Season tickets usually generate detailed personal data about the purchaser, such as their address, date of birth, bank details through their payment, and gender. Ticket use will generate detailed trip data linked to a person if the public transport (See Passenger Transport) system uses gates, readers or scanners such as the one illustrated in the figure below. Individual “paper” tickets, as a rule, would only generate data about the location of the purchase and the trip. It is good practice to offer anonymous ticketing and cash payment options whenever possible.

Figure 2: Smartcards for Public Transport Ticketing (Transport for London)

The movements of trains, buses and other forms of public transport are often controlled and/or monitored by ITS – and so, record data. This can lead to privacy (See Privacy) issues for drivers and other staff – and their representative bodies – such as driver associations or trade unions – voicing concerns. On the other hand, location applications can improve the safety of public transport staff.

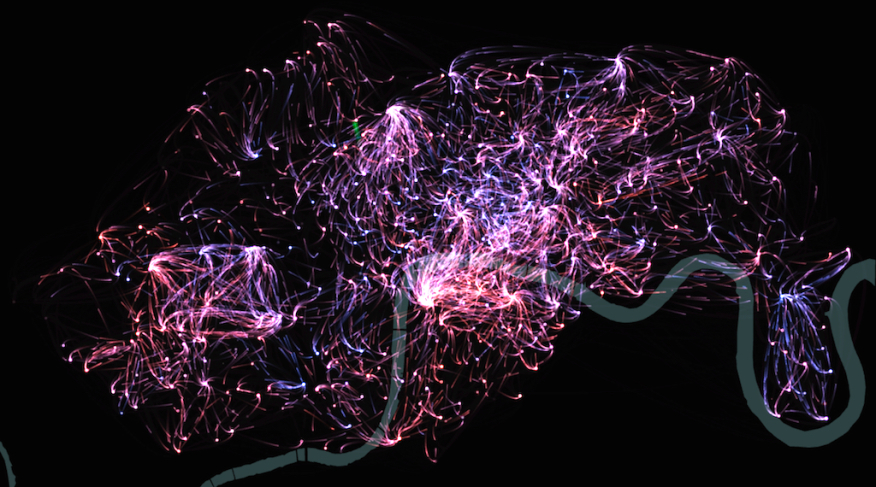

Data are generated through many different ITS traffic management systems in use (See Network Monitoring). Vehicles are identified and their location, direction of travel, and speed is recorded – both to enable optimal traffic management at the time, and for future modelling and forecasting. The figure below shows how data from London’s cycle hire scheme can be used to visualise cycle traffic movements. This type of data collection may be completely impersonal – such as loop detectors which only establish that a vehicle is there and the speed at which it is travelling. It is also capable, though, of detailed personalisation – if the vehicle is identified by ANPR and an image captured enables the identification of driver and passengers. Good practice is to only record the data needed for the job in hand, and to irreversibly encrypt or discard the rest.

London Cycle Hire Scheme – Visualising Cycle Movements (Illustration courtesy of City University London).

If an accurate tolling (See Electronic Payment) charge is to be levied, a lot of personalised data regarding the vehicle, its keeper, its location and possibly its exact trip details, and the customer’s bank details – have to be recorded. Good practice is to discard this after an agreed period – after which the driver no longer has a of challenge against the charge.

New ITS applications of driver support systems (See Driver Support), autonomous vehicles and cooperative systems need to be considered carefully before establishing good data handling practice. These systems rely on an enormous amount of location and trip data in order to be safe and effective. There is no reason, though, why this data should be kept and stored after completed trips without being made anonymous.

A fairly new area of ITS data is crowd-sourced data. Social media and technology – such as Bluetooth (See ITS Technologies) - offer the opportunity to generate or collect comprehensive and detailed travel data relating to individuals. This can either be with their active or implied consent – or without their knowledge. For instance, a keen user of social media who uses platforms such as Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn and TripIt to broadcast their whereabouts can be considered to be consenting to their travel profile being constructed. By contrast, logging the movements of somebody who has not realised that their phone has Bluetooth and that it is enabled – is at the other end of the scale and can be reasonably considered as an invasion of their privacy. They have not consented to their data being used and are not aware that they are generating data. In many countries, the fact that they are anonymous would still not make it acceptable to use their data.

Most ITS implementations generate, use and store quantities of data which are enormous by the standards of even only ten years ago. Much of this data is highly personalised and very sensitive. Many countries recognise, in law, the of individual citizens not to be excessively surveyed, monitored, recognised, and recorded.

Legislation to regulate data is cast to cover a variety of scenarios. It applies to drivers and passengers just as it does in other areas of life – such as voters and bank customers. Those handling ITS data (traffic control centre operators, electronic payment back-office operations, information service providers, for instance) will be subject to the regulations in place in their countries. Data collected and processed in a control room for instance, must be kept secure from unauthorised access and misuse. The principles behind data regulation should apply easily across sectors. ITS practitioners should bear in mind that digital camera images (such as images captured for traffic or payment enforcement) are classified as data.

Data Control Room (Copy ITS United Kingdom)

ITS practitioners processing data should have access to simple and clear codes of practice, drawn up by their employing organisations on the basis of advice from those with suitable legal expertise. These codes should ensure that national legislation is followed but also add a layer of good practice relating specifically related to ITS. Training and monitoring of staff is essential to ensure that any code of practice is understood and adhered to. It should form part of the management culture of all ITS workplaces where data is processed or stored.

One reason why people distrust the collection of data by – by and for – ITS systems is the suspicion that the principles of personal data protection are overlooked or deliberately ignored. For example, if a request is made by the police or security agencies for access to personal data on journeys and locations, will the ITS data owner provide it? Are there requirements in place that govern how police and security requests are handled?

There have been examples where location data from an ITS source has been used as evidence in civil and criminal proceedings to prove that a defendant was present at a specific location and at a specific time. There are also cases where the defence has challenged the legality of the data capture, its accuracy and even its use. If the data is inaccurate, should have been destroyed or made anonymous under data regulation legislation, it may be ruled as inadmissible.

The best way of keeping personal data secure is not to expose it to the risk of theft or misuse – by minimising and making it anonymous it wherever possible. Where sensitive data has to be kept, it is essential to ensure it is stored and handled in compliance with legal requirements and good practice.

There will almost certainly be national legislation affecting how personal data should be stored and kept safe. Complying with legislation alone though, is not likely to optimise data security. Expert advice should be sought from specialists or by retaining expert capability in-house. While external, malicious attacks from hackers aimed at financial gain or disruption are often seen as the most likely security risk, organisations should also be aware of the possibility of attacks from staff who may, for some reason, misuse or misappropriate data to which they legitimately have access at work. There are also potential risks from staff who are incompetent, unlucky, or badly supervised, and who can do as much damage as an external hacker without intending to.

Data security threats evolve and renew daily. The security regime in place must be designed to recognise this so that the defensive measures keep pace with threats.

Good practice in ITS data security can be summed up as:

The growth in the amount of data used and created by ITS and the increasing depth and coverage of this data – often personalised and with reference to time and location – make privacy considerations increasingly important in ITS. The capabilities for collecting and storing personal data are very well developed. For example, when using public transport the use of an electronic ticket and the deployment of CCTV cameras at stations, stops and on vehicles gives access to data such as a person’s name, address, date of birth, gender, bank details, place of work and other places regularly visited. The data may be combined with the use of software that recognises faces, a way of walking or other types of movement such as running.

A driver of a private vehicle may have a similar level of detail recorded about themselves and their vehicle – such as driver licensing and insurance arrangements, the payment of vehicle taxes, fees and tolls , and monitoring of the vehicle for traffic management purposes, parking enforcement or tolling.

There are a number of definitions of privacy from that offered by Google to Article 12 of the UN Declaration on Human Rights (1948):

“No one shall be subjected to arbitrary interference with his privacy, family, home or correspondence, nor to attacks upon his honour and reputation. Everyone has the to the protection of the law against such interference or attacks.”

Sensitivity to privacy varies greatly between countries and cultures and this is one area of ITS where local knowledge of, and understanding what is acceptable and what is necessary is necessary for each deployment. For example, in the UK the prevalence of closed-circuit television (CCTV) surveillance in towns and cities, buses and trains, means that the average Londoner appears in camera shot 300 times a day – the figure below provides an example. Some people find this unacceptable; others accept that being observed and even actively monitored is a consequence of travel in this day and age. One person’s privacy can be another person’s danger. CCTV monitoring of motorways (See Network Monitoring) may be regarded as a loss of privacy for drivers, but if the operator spots a “ghost driver” travelling along a motorway in the wrong direction, it can save lives.

Street scene in London showing CCTV camera above VMS for Olympic Games (copy ITS United Kingdom)

Camera technology provides the basis for many ITS application such as enforcement of traffic laws and electronic payment in tolling and ticketing. Vehicle licence plate recognition and facial recognition software depend on the capture of digital video images. Enforcement notices rely on camera images to identify the offending vehicle and – in some cases – the driver. A photograph of the whole front of the vehicle may remove any doubt about who was driving the vehicle at the time of the offence but in some countries this is considered an unacceptable intrusion.

One general principle is that privacy can be traded for benefits – such as correct fares or safety. The technology allows the traveller to be charged the amount to use public transport, and may increase personal safety or ensure that traffic information provided is relevant. If the intrusion into the individual’s privacy is seen as benign and fair, public concerns are also lessened. For example, in the event of a serious road accident, eCall (the European Union’s collision notification system) automatically initiates a 112 emergency call from an in-vehicle device to the nearest emergency centre with details of the vehicle’s precise location. (See Driver Support)

Another principle concerns the storage of information. Digital images and other personalised data (for example details of a journey or a transaction) may be stored and held in a computer’s cache memory for the benefit of the police, road authority or transport operator – but the individual may not benefit from this directly. Good practice requires that data is made anonymous or reduced (by discarding the data elements not needed for a specific purpose) and eventually deleted (by setting a sensible deadline in terms of the purpose of use, after which the data will be destroyed).

The practice of making data anonymous may to help to allay suspicions about potential misuse and concerns about data security, criminality and identity theft. Payment transactions that involve details of credit card accounts are especially vulnerable. For instance, when a person passes through a ticket-operated barrier to use public transport it is not necessary for the operator to know the name of the user or their credit card details – only that the ticket is valid. Once this has been recorded, all personal data relating to the ticket holder can be discarded – retaining only data that is essential information for transport management purposes, such as trip origin, destination, fare paid and timing.

As camera and other sensing technology become more sophisticated, privacy will increasingly be at risk. Undertaking a proper impact assessment of privacy issues for each camera deployment can mitigate the risk. Any formal or informal assessment of risks to privacy must take account of national laws, regulations or codes of practice and factor in variables such as what may be acceptable to data subjects, what is socially desirable (for example for law enforcement or road safety) or commercially attractive such as a product loyalty card. Proper consideration of privacy issues must be based on reaching a consensus on the acceptable balance between loss of privacy and the achievement of objectives – such as seamless journeys.

During recent years, the concept of Open Data has been widely promoted in Europe and North America. The basic principle is that if the data has been collected at public expense, it should be made available to anyone to use. This policy has been adopted by governments in the interests of transparency and accountability and to stimulate innovation and the development of added-value services and products. In Europe, the EU is a strong supporter of Open Data as a principle, and similar trends can be seen elsewhere in the world. Open Data is a concept, which particularly applies (but not exclusively) to public sector information. The transport sector includes major datasets owned by the transport industry in the public and private sectors (datasets such as timetables and real-time running information). To deliver a comprehensive open data policy for transport, these bodies need to come together to support the agenda.

An open data policy raises many challenges – such as privacy and personal data, commercial confidentiality, data quality and accuracy, and – not least – the cost of making data available. Many public sector data owners across the world have developed workable solutions for dealing with these. This includes making anonymous or removing personal data and implementing policies on charging for re-use of data in line with local/national policy or practice.

In 2012 it became UK government policy for each government department to publish an Open Data Strategy setting out what data sets it would make available over the next two years, and how it would stimulate a market for its use. A UK Open Government Licence has been developed to provide a common set of terms and conditions on the provision and use of public sector information. Government-owned datasets can increasingly be accessed from a “data warehouse” that is being developed into a National Information Infrastructure so that the most critical government data can easily be sourced from one place. (See: http://data.gov.uk )

The Department of Transport’s Open Data Strategy outlines the principles behind its data collection, management and release policies, and lists available data sets. These include core reference datasets (also known as “big data”) – that cover definitions of transport networks, timetables/traffic figures, planned/unplanned disruptions and performance figures. The strategy also signposts potential users to the type of licence needed to re-use the data. (See http://data.gov.uk/library/department-transport-open-data-strategy-refresh).

Intelligent Transport Systems are a “data-rich” and reliant on data and information. ITS needs data to operate, it creates data as it operates, and retains data after operations are complete. It includes data about transport networks (such as roads) and data about transport movements on the network (traffic counts, bus timetables, passengers and freight).

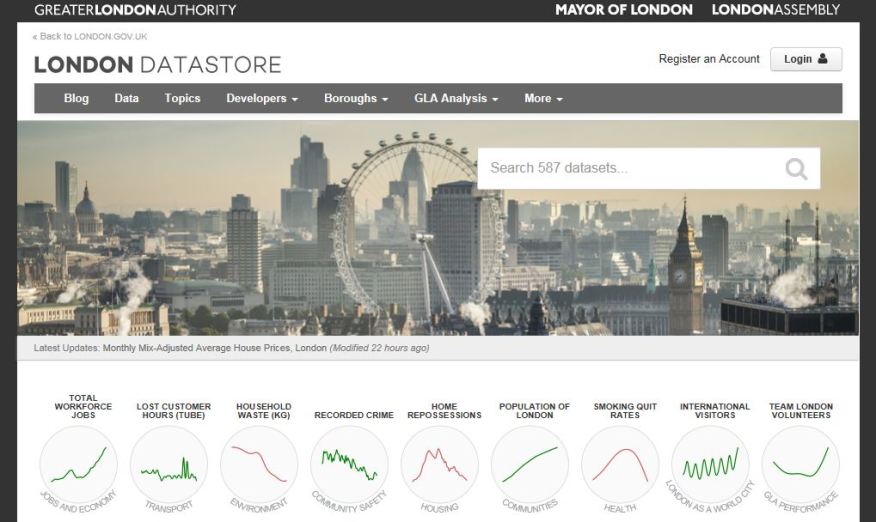

There is strong public interest in transport information – which can be used to inform travel choices, to improve performance and to hold operators and Government to account. Many organisations or individuals, other than the original data owner, can see value in the data – to create services or undertake research – for both commercial and non-commercial purposes. For them, a “data warehouse” provide a wealth of information. An example is Transport for London’s , London Datastore website, which provides access to large data holdings about London – as the figure below, showing its homepage, illustrates. (See Case Study: Open Data UK)

London Datastore (Source – homepage of http://data.london.gov.uk/)

It is widely accepted that the data owner should not be expected to carry out a lot of work or incur a lot of expense to process the data to make it is more useful to those who wish to use it under Open Data arrangements. The data owner’s duty is usually limited to making the data available in its original state, when it was collected or used. The data owner may make its data holdings accessible through a dedicated website or by providing contact details for requests and may charge the data re-user for access to recover the cost of making data available.

Data owners often require those accessing the data to provide basic details of who they are and their intended purpose of use (to prevent inappropriate use). It has also become common for the original data owner to require data re-users to accept liability (See Liability) for any damage or loss sustained as a result of the service or product they create using the data. This may be achieved through a simple disclaimer tied to the accessing of the data. It is essential that no personal data is made available without being made anonymous.

The principles behind access to Open Data in ITS are gaining ground, and major users of data for ITS applications and services – such as Google and TomTom – see value in more and more countries adopting the policy.

Once a decision has been taken to embrace the Open Data concept, simple principles of good practice should be followed:

Procurement of ITS on behalf of roads authorities is usually done by public bodies who are obliged to follow local competition law, contract regulations and procurement practices. When ITS is procured by a private company, there may be more freedom in the procurement processes used but national and international contract law will still apply. Where international treaties are in place, such as in the European Union, there may be procurement regulations that operate across national borders to ensure open markets. (See Procurement Methods)

Competition and procurement are areas of ITS where the processes from the pre-ITS era – such as traditional contract practices for roads and highways – may not be appropriate. Procurement processes which have worked well – sometimes for many decades with little change – for the construction, maintenance and upgrade of infrastructure such as roads, bridges, tunnels and street lighting – do not work so well for ITS which is affected by the rapid pace of technological change.

There are various solutions to these problems. They include requiring an ITS supplier to conform to international standards and/or local system architecture requirements, (See ITS Architecture and ITS Standards) or to meet functional performance specifications that leave the preferred design option open rather than being highly prescriptive. Complaints about the client over-specifying the components and methodology of the procured ITS solution are common. It is good practice for the client to be specific about the required outcomes and services, leaving the supplier free to choose the most appropriate means of delivering these outcomes. The supplier must be prepared to justify their choices and demonstrate that they will meet the client’s requirements.

Inflexible procurement procedures can lead to suppliers being unable to offer the best price for the best service, or the best technical solution. This may be reinforced by a risk-averse culture within the procuring organisation that means innovative solutions are disregarded. Inflexible procedures can also dampen innovation in the market. This may impact on ITS suppliers who have a unique and cost effective concept but find that public procurement rules frustrate their realisation of its commercial potential. The only way to market the concept may be to participate in an open competition procurement process held by the authority for bids based – directly or indirectly – on the supplier’s concept. The downside is that this requires the authority to share details of the supplier’s concept with other bidders – whereas the supplier with the concept would doubtless prefer a contract awarded on a single tender basis.

A further complication is that ITS is often procured using a process of pre-qualification in order to assess supplier competence and suitability and create a short-list. It is also common for a public authority to set up a framework contract or framework agreement with authorised suppliers, which can impact negatively on small and medium sized enterprises and may restrict the number of players in the supply chain.

Many countries follow strict practices in relation to purchasing and commissioning infrastructure, equipment and services by public authorities. This is to ensure fair, honest, transparent and value for money procurement. Where such frameworks exist, publicly funded spending on ITS systems and services will be within scope of the rules, often as part of a larger scheme, such as the building of a motorway where ITS is a component.

The details of procurement rules and practices and the methods for enforcing them vary from authority to authority and in some cases region to region. The intention behind the rules is generally always to ensure that the public receives best value from public expenditure, by ensuring that the best possible bid is successful. (See Case Study: ITS Procurement USA)

In ITS terms, the “best” bid would normally be the one that offers an optimum solution in terms of meeting all the deployment objectives for the project or scheme. A number of factors may have a bearing on the choice of project contractor or equipment supplier. Some countries have developed specific requirements that are imposed on ITS deployments. For instance, they may require compatibility with a national or regional ITS architecture or a good grasp of international ITS standards.

Contract award criteria may need to include whether the systems are robust, easy to operate, as cheap as possible to install, operate and maintain without risk to reliability, inter-operability with existing systems, and future “lock-in” to a particular supplier. The preferred bid may also need to demonstrate compliance with relevant international or local standards, national or regional ITS architecture, and available telecommunications (See Planning an ITS Programme, ITS Architecture and ITS Standards).

In many countries litigation by unsuccessful bidders for public sector contracts is on the increase, and ITS is seeing its share of this. Relationships between authorities and contractors inevitably form – and may be formalised through long-term call-off contracts making it difficult to test the market with new suppliers.

A recent European Commission project (P3ITS: See www.P3ITS.eu ) looked at pre-commercial procurement for ITS. The intention was to produce guidelines that would help a public authority to support the pre-commercial development of innovative ITS solutions by private companies in trials prior to large-scale market deployment. The challenge was how to do this without the market procurement being considered anti-competitive on the grounds that a supplier not involved in the original trials might be at a disadvantage – not having had the opportunity to take part in the trials. The European Commission believes that the P3ITS project came up with credible solutions to this problem. (See Case Study: Pre-Commercial Public Procurement)

Where public procurement rules apply, the evaluation of proposals for ITS systems and services must be done systematically and rigorously. The procedures must ensure a fair outcome that matches the project requirements and will stand up to scrutiny, especially by those suppliers who are unsuccessful against their competitors.

A key issue for a public authority procuring an ITS scheme, is the choice of criteria against which the suppliers’ bids are evaluated and scored. Failure to apply the award criteria strictly can be a source of challenge to the procurement. Good practice means that award criteria, scoring thresholds and their weighting should be specified and made known in advance. Demonstrating fairness in awarding contracts beyond all doubt can be difficult when such a wide variety of considerations come into play.

There is general agreement that the best results are obtained by specifying the outcomes and services required from the supplier, not the technical detail of how these are to be achieved.

The procedures that have been developed for use in purchasing IT systems may often be more appropriate for ITS procurement than traditional models used for civil engineering works by a roads authority. If the road authority’s procurement processes for ITS do not work well, because they have been designed for major infrastructure projects, a useful first action is to consider whether IT procurement processes would be more appropriate. Perhaps a hybrid of the two can be developed without breaking existing guidelines.

Liability in the legal sense concerns responsibility by an individual, enterprise other organisation for its actions and the conduct of its contractual obligations.

“Legal liability can arise from various areas of law, such as contracts, tort judgments or settlements, taxes, or fines given by government agencies”. (Wikipedia)

The legal liabilities of authorities and commercial companies that provide ITS services and equipment can arise in many different ways. Proper consideration of liability implications should form part of the planning of any ITS implementation as well as the design and manufacture of any ITS components. The more an ITS application is automated or “authoritative” in the advice it issues, the more it replaces the need for actions or decisions by users, diluting their responsibility and liability. Many everyday ITS installations are safety critical – such as the advisory signal system illustrated in the figure below.

Advisory signals for cyclists and pedestrians

The allocation of responsibility when something goes wrong can become more blurred. The balance of liability between the ITS user, developer or provider is open to debate and may change – either through case law establishing new legal precedents or through new legislation being enacted.

The United Nations Vienna Convention on Road Traffic (1968) requires that every moving vehicle or combination of vehicles shall have a driver, and that the driver shall at all times be able to control the vehicle. These requirements are fundamental principles of liability in road traffic scenarios. As ITS evolves into a “systems of systems” – with information inputs from many different sources being processed and turned into advice, commands or automatic actions in-vehicle – the question of liability becomes less clear cut. On-road testing of cooperative systems and autonomous vehicles is happening now and the time is fast approaching when the framework for road traffic liability may need to be revised.

Liability issues are often cited as a barrier to the deployment of future ITS applications such as autonomous vehicles and cooperative systems. (See Driver Support and ITS Futures) It is worth remembering that similar concerns were voiced in the past about Advanced Driver Assistance Systems (ADAS) such as assisted braking or assisted parking and whether they would lead to large numbers of liability lawsuits. These systems are now in full production because the automotive industry was satisfied that the liability risks were outweighed by the benefits and commercial returns. The same judgements have been made in relation to Intelligent Speed Adaptation (ISA) (See Intelligent Speed Adaptation), which is now deployed in public fleets in several countries.

A pattern emerges from the examples above, which suggests that any ITS development that reduces the need for actions or decisions by the user or transport provider should be subject to a risk assessment. It will only be successful in the market – achieving widespread acceptability – when public confidence is won.

Most countries will have a legal liability regime that will impact on ITS implementations. This can vary between countries and regions. Sometimes the law and accepted practice will be in harmony, and sometimes they may conflict. When considering the liability issues of an ITS implementation, the regulatory framework needs to be taken into account to make sure that legal liability is not overlooked.

The universal principles most broadly adopted are that a product:

While conditions of usage and disclaimers can be used in a contract, these cannot remove the of the user or purchaser to expect the product to perform to a reasonable standard.

A highways authority may purchase traffic signalling equipment and then argue that its breakdown rate is unacceptably high, seeking redress from the supplier. In mitigation, the supplier may point out that:

The legal definition of negligence, and how negligence is dealt with in law, varies from country to country. As a general principle, a charge of negligence in ITS implies that the provider of a service or product has breached a duty of care to the customer or user, who has suffered injury or loss. The burden of proof is applied in different ways and to different stakeholders in different countries – and the definition of what constitutes “loss” can also be different. A good guide for an ITS implementer is to look at previous legal cases involving allegations of negligence in their country – to draw informed conclusions about how to avoid similar problems arising when their ITS is deployed. It is difficult to think of an everyday case within ITS where negligence could be proved in the current legal and policy situation. This may change if ITS cooperative systems (See ITS Futures) become widespread – since here the driver is much more dependent on the actions of others, whose duty of care to the driver becomes correspondingly greater.

a driver may argue that they were injured in a crash which would have been avoided if the highway authority had adequately informed him via Variable Message Signs or radio messages of poor road conditions – perhaps icy road surface or poor visibility. This would normally fail, as the court is unlikely to agree that the road operator’s duty of care to the driver extends this far – determining instead that drivers are responsible for monitoring road and weather conditions themselves:

a train passenger may argue that the fare paid is too much because the train operator did not provide adequate information about cheaper tickets available. This too would most likely fail, for the same reason.

In ITS, contract law will usually apply to an authority purchasing a service from a provider, and to the purchase of ITS equipment. In the case of navigation systems (See Driver Support) and ADAS, the purchaser would be an individual person. A contract relating to ITS is enforced in the same way as any other contract. Disclaimers and other statements in the contract intending to limit the liability of either party will only be enforceable if they can be considered to be reasonable, fair, and compatible with related principles such as duty of care.

a driver may purchase a navigation system and use it for work as a lorry driver. If the system regularly redirects the driver to routes unsuitable for the vehicle, the driver may regard the product as defective and seek redress. The challenge will be unsuccessful if the product was intended for private car use rather than use in a lorry. A challenge would only be successful if it could be proven that the navigation system was designed specifically for use in a lorry of the size and class used

a public transport operator (See Passenger Transport) may contract with a service provider to process its ticketing transactions, with the contract stating that 98% of transactions will be correctly processed. If spot-checks and customer complaints show that in fact only 85% of transactions are correctly processed, a claim by the operator against the service provider is likely to succeed. However, the service provider will try to identify and prove failings by their customer as mitigation – such as wrong passenger information or failure of customer-owned equipment.

This is usually more of a background consideration when considering liability in ITS – but it does need to be taken into account. An example is those countries where fault automatically lies with the vehicle driver if a vehicle collides with a pedestrian or cyclist. This can lead to a complex situation if any of the parties in the collision were being influenced by an ITS implementation which failed to work properly.

From the 1980s onward, when use of ITS became mainstream, there have been surprisingly few examples of litigation regarding liability in the area of ITS, as compared with the level of nervousness and uncertainty that the issue generates. This is likely to be, in part, because all parties have taken due care in assessing the risks and benefits. It is also helped by the flexibility of legal systems to apply basic principles (such as reasonableness or proportionality) to situations involving new and complex technical applications.

We are now at the stage where on-road implementations of cooperative systems and autonomous vehicles (See ITS Futures) appear certain to become a reality in some countries over the next ten years. Once the systems control the activities of vehicles – with no realistic chance of a timely human intervention – it may be appropriate to move liability to the system providers and the information providers who serve them.

Some cite the Vienna Convention (1968) as a barrier to these developments. It is far more likely that the safety and environmental benefits of cooperative systems and autonomous vehicles are attractive enough to create a consensus that its principles will have to be modified.

The area of liability in ITS is complex, but with the possible exception of autonomous and cooperative systems that are making the transfer from research to full-scale deployments, it is no more complex than liability in other sectors. Many people become concerned with liability issues when:

Risk and impact assessment of new and updated ITS must always address liability issues. This should be formalised in the process, so that lessons learnt are carried forward from one implementation to the next.

It is also important to seek appropriate professional legal advice. When implementing any specific ITS for the first time in a country, time spent discussing potential liability issues and working on solutions will repay itself many times over during the lifetime of the ITS. A specialist in national liability law will be able to identify the potential issues, and the ITS practitioner will almost always know how to mitigate them once they have been pointed out.

In countries with well-established ITS, there is usually a small number of legal experts specialising in ITS issues. These are well placed to comment on complex issues. In developing economies, a general liability specialist will usually have the knowledge and expertise needed.

Where other countries have already demonstrated that an ITS implementation can be undertaken and no significant liability issues arise – practitioners should feel confident that if they proceed with due regard for relevant national legislation, they too should be able to avoid these problems.

Those considering pioneering use of ITS – not yet tried on-road elsewhere – should proceed with caution and give as much weight to liability issues as to ITS technology.

Enforcement agencies in many countries use ITS to assist with their work on road safety and traffic legislation enforcement. Examples are speed enforcement cameras, red light enforcement cameras (such as the one illustrated below), Weigh in Motion (WIM) and vehicle self-monitoring applications such as in-motion tyre condition monitoring.

Red light enforcement camera (copy CA Traffic)

There are specific systems to detect offences such as red light running or speeding. In many cases these systems automate the process from detection of the offence to issue of a fixed penalty notice to the vehicle keeper or driver. There are also surveillance systems that are used to spot drivers going the wrong way on the carriageway, stopping in no-stopping zones such as tunnels, or parking illegally.

Other systems are aimed at preventing offences and violations, such as “alcolock” breathalyser immobilisers and Intelligent Speed Adaptation (ISA) (See Driver Support) which are capable of preventing the commission of offences in the first place (drink driving or speeding). They double as driver support systems as well as enforcement systems.

Schemes where drivers have to pay to use the road or to park would be pointless without an enforcement regime, as very few drivers would pay unless there was a realistic risk of incurring penalties. Tolling (See Electronic Payment) and parking often use ITS to enforce correct payment (See Case Study: Free-flow Tolling, Chile).

The prevalence of ANPR for these processes is interesting. The London Congestion Charge in 2003 was criticised by the ITS profession for being ANPR-based when newer technology such as satellite or tag based charging could have been considered. At that time, many also expected Electronic Vehicle Identification (EVI) to be just around the corner – ready to replace number plates as the first means of identifying a vehicle. Ten years later, ANPR remains very widely used to identify vehicles, and EVI seems to have lost momentum through lack of acceptability, mainly based on privacy concerns. (See Privacy)

Automated enforcement is only possible if the device and the evidence it provides is reliable enough to withstand the test of authenticity in court. Having a regulatory framework and systems and procedures for end-to-end verification of enforcement operation is the key to success.

The transition for a situation where a person detects an offence and initiates a prosecution or issues a fine – to a situation where an automated system carries out these tasks – cannot usually be managed within a regulatory or legislative framework that predates automation. Since any change to the framework will usually need to allow for the automatic identification of vehicles and their location – due regard must be paid to issues of privacy of the driver. (See Privacy) An appeals process is good practice.

An example of a successful appeal is an incident where a vehicle was filmed making an illegal turn triggering the issue of a fine. Out of camera shot, behind the vehicle, was an ambulance on call. The car driver was making the illegal turn as the safest way of letting the ambulance pass by. The fine was cancelled on appeal.

These can be enforced using either semi or fully automated systems. (See Enforcement) Typically, a camera is used to record the offence and, via Automatic Number Plate Recognition (ANPR) to identify the vehicle. How the offender is then contacted and penalties are issued, will depend on the legal framework in a specific country. Usually, legislation will have been enacted to govern contact and enforcement processes in the way that authorities wish to handle traffic management infringements. If the law allows full automation without any human verification, the system can issue and post the notice of a fine or a summons to court. If not, there may be a requirement for a person to check the image, verify the offence and/or the identity of the vehicle, in order to authorise the next step of the process.

Offences such as driving the wrong way on the carriageway or a ramp, or stopping where this is not allowed (such as in tunnels or on bridges) can easily be detected using CCTV. Previously, detection would mainly have been carried out by control centre responsible for monitoring computer screens and taking manual action when spotting dangerous driving. It is now becoming more common to use video analysis of images to create alarms to alert staff. The system itself does not undertake the enforcement. If appropriate, enforcement officers will be despatched to detain the offending driver.

Where specific taxes, insurance policies, or certificates of road worthiness are associated with individual vehicles, Automatic Number Plate Recognition (ANPR) offers a simple way of linking the vehicle with its centrally held record and checking if all records are in order. If not, the vehicle can be stopped and appropriate action taken.

A new development is more sophisticated use of surveillance technology, both camera- and radar-based, which detects infringements – such as following too close to the vehicle in front, or illegal lane changes.

Remote, camera-based surveillance can also be used to detect offences such as not using seatbelts, using a mobile device in an illegal manner, and even smoking in situations where this is illegal in a vehicle. (See Policing/Enforcement) Again, the image captured by the camera will be used to provide evidence for a fine or a summons.

ITS for parking management, including parking enforcement, are now common. In the case of enforcement, cameras and ANPR can be used to detect parking where it is not permitted, or to detect overstaying time limits in legal parking places.

The enforcement of charges relating to parking and tolling is an important and widespread ITS application. (See Electronic Payment) All tolling systems, whether large scale motorway tolling or individual bridges or tunnels, rely on adequate enforcement to function. Reliability of equipment and procedures is key. If the system states that a vehicle parked in a certain location, or was present in a tolled area, at a certain time, the operation of the equipment (such as its reliability and time/place accuracy) should beyond dispute. (See Case Study: Stockholm Congestion Tax)

Tolling schemes that rely on RFID tags can be enforced by detecting and stopping vehicles without tags. Schemes where the vehicle number plate is associated with non-payment of the toll are enforced by camera. The vehicle keeper will be fined if the vehicle is shown to have incurred a charge that has not been paid. As with parking enforcement, a vehicle with numerous outstanding payments is likely to be eventually listed as “of interest” and a special effort made to find and stop it the next time it is picked up by cameras.

To enforce payment, it is essential that all the ITS equipment used complies with type approval and other legal requirements in the country of operation. (See Case Study: Type Approval (UK) )

ITS enforcement applications for freight are common. (See Enforcement) One that is so ubiquitous that it is often overlooked is digital tachographs used for certain classes of heavy goods vehicles. This collects and presents information needed by law enforcement officers who are investigating whether driving hours and rest break legislation is being followed, It is done in an easily downloadable and tamper-proof way – and offers the possibility of remote interrogation.

Weigh in Motion (WIM) is another important freight application that enables the detection of overloaded vehicles without having to stop the vehicle for a manual check. The overweight vehicle is brought to the attention of enforcement officers on the road ahead, who have powers to stop the vehicle. Automated processing of fines for overweight vehicles is rare. An overloaded heavy goods vehicle is often associated with other offences – such as drivers’ hours, illegal condition of vehicles, or regulatory offences by the owner. A physical vehicle stop is often useful in bringing these related offences to attention.

These are systems (See Driver Support) that prevent – rather than detect – offences. Examples are driver drowsiness detection, which can help to stop the driver from committing a variety of dangerous driving offences:

Systems that monitor the driver’s fitness to drive are increasingly being installed in new vehicles. Alcolocks and ISA are common in public fleets in the Netherlands and Sweden. These systems have much to offer in supporting road safety, but they do also raise issues of liability. (See Liability and Privacy)

Using ITS for road traffic law enforcement is a very important ITS application which, while not always popular with the public , have already saved many lives by preventing road accidents.

It is worthwhile keeping up with new developments (See ITS Futures) in using ITS for enforcement purposes. It is not so very long ago that Weigh in Motion (WIM) was a new application – whilst first uses of technology to check tyre condition on moving vehicles are now taking place in Germany.

Practitioners should be mindful of how unpopular some applications are with drivers – such as automated parking enforcement and speed enforcement cameras – in particular single fixed point speed cameras rather than point to point enforcement cameras where the vehicle speed is measured and calculated over a length of road (such as a kilometre).

The unpopularity of measures can lead to challenges to enforcement proceedings . Challenges are often made on the basis that the equipment used to detect the offence was faulty or not legally compliant in some way – and that there was no offence. To deter spurious legal challenges it is important to keep the equipment type approval, calibration and maintenance regimes up to date, transparent, and well publicised. (See Case Study: Type Approval of ITS Devices)

One way of overcoming resistance to enforcement measures is “marketing” activity to publicise the positive outcomes. This can help prevent public opposition and political lobbying. In Ontario in Canada, this eventually led to speed enforcement cameras being removed from the roads.

When using ITS equipment for enforcement purposes, the equipment must be certified according to the regulations of the country. It would not otherwise be workable to prove the integrity of the equipment each time the evidence it produces is used in court. The certification process allows the whole court to accept that the evidence is truthful and reliable. It removes what would otherwise be a standard defence: that the equipment does not function accurately or within the law being applied. (See Case Study: Type Approval (UK))

Different, un-harmonised, national certification regimes are not popular with equipment manufacturers who have customers in more than one country with different traffic laws within which the equipment has to operate effectively. There has been some work within the EU towards achieving agreement on issues of certification – and it may be that in the future the situation will become less fragmented within the EU and more globally.

When using evidence in court, produced by an ITS application – such as parking monitoring systems, speed cameras, or an ANPR camera at a bus stop (as shown in below) – the images or data produced as evidence must be tied to the date, time, location, and vehicle. The purpose of the certification process is to ensure that the design and construction of equipment is fit for purpose. In other words, if the certified equipment has recorded that a vehicle was in a certain location at a certain time, this is beyond question, provided that the equipment is installed and maintained correctly. Information has to be recorded accurately and stored securely, so that it cannot be corrupted or changed. The authority may need to demonstrate that they have adhered to the maintenance and calibration regime laid down during the certification process.

ANPR enforcement camera at a bus stop (Copy Zenco Systems)

In courts where uncorroborated automated evidence is not allowed, an officer will need to attend to testify that they observed the activity captured by the system, at the time recorded by the system.

The legal processes and equipment certification connected with using ITS equipment for road traffic law enforcement can only be successfully assessed by collaborative working of legal and technical experts. It is very rare to find all the expertise needed in any one individual – whether it be the technical expertise relevant to camera lens grinding, the data management expertise needed for secure data transfer, or expertise in road traffic law.

There are examples from different countries of how this may be achieved. In some countries, a national transport research facility undertakes this work and advises practitioners. In others, the national police force has the research facilities to do so. Another solution is for the Justice Department (or its equivalent) to be the provider of this expertise. Informal forums where equipment suppliers, users, and legal experts can come together are also very useful. These groups may be run by police forces, equipment manufacturers, or national ITS associations.

Anyone considering introducing automated enforcement into a country for the first time should seek informal advice from colleagues in countries where it is established practice to use ITS for enforcement. It will never be possible to simply transfer systems across borders, due to different national legal frameworks – but it will be invaluable to find out how others have ensured that their systems are legally and technically robust. Contacts at government, police force, or national ITS association level can help with this.