Monitoring and evaluation are two important aspects of Road Network Operations (RNO) that are often overlooked. Both have a central role to play in ensuring that the policies adopted for RNO and the measures applied actually achieve the desired results. This is especially true for measures that fully exploit the potential of ITS technologies, which have opened up many new possibilities in recent years. Monitoring and evaluation are significant for ITS deployment in general and for ITS in road network operations in particular – acting as tools to assess the contribution of a scheme to meeting policy objectives, to improve operations and influence future deployment strategies. (See Strategic Planning)

As can be seen from the coverage of this website, ITS is applied in many different ways and different contexts, including:

Careful monitoring and evaluation will contribute to successful operations in all of these areas, but especially so for the central activities of RNO. ITS has great potential to enhance the efficiency of the road network itself – for the benefit of the road users – for example with operating systems that automatically respond to recurring congestion, traffic incidents or weather events. None of these improvements is guaranteed and public perceptions can be very different to the reality. There is often a need for objective assessment. Success often depends on the manner in which the technology is deployed and the operating methods adopted. For these reasons monitoring and evaluation are essential parts of the RNO programme that help determine priorities and secure value for money. They are not an optional extra.

Monitoring and evaluation help to:

Some examples of key RNO objectives – to which ITS can contribute – and which can be informed by monitoring and evaluation that are suitably planned, include:

Monitoring involves continuous and systematic data collection to assess the performance of a system in meeting key indicators. Monitoring can be used to measure the impacts of a scheme as input information for its evaluation.

Evaluation is an assessment of the extent to which a scheme meets its objectives. It provides feedback which is useful for improving performance in the future. This, in turn, provides information for appraisal decisions before investments are made in ITS.

Monitoring and evaluation are activities that are carried out after ITS has been deployed. They are distinct from appraisal, which is part of the planning process undertaken in support of investment decisions when an ITS scheme is in preparation, prior to deployment (See Project Appraisal)

The term ‘evaluation of ITS’ is an assessment of the extent to which an ITS scheme has met its objectives. It provides lessons on improving performance in the future. The main issues to consider are:

The road network operator can play an important role in the evaluation of ITS deployments aimed at supporting Road Network Operations. Positive and negative impacts on network operations should be assessed for any ITS applications that are in the research and development phase or are part of a large-scale field trial. Evaluations of routine deployments of established ITS technologies are also important to establish good practice. For example an evaluation of the use of speed cameras in a completely new context should establish the degree of compliance by road users and whether this has a beneficial effect on traffic efficiency and accidents.

The evaluation is a planned and structured assessment of the impacts of an ITS scheme and the extent to which it has met its objectives. The impacts assessed include the financial costs and negative consequences as well as the benefits. (See ITS Benefits) Evaluation takes place after deployment has been completed, but it is important to plan the evaluation before the deployment takes place and schedule the resources to carry it out. Evaluation is often undertaken by an independent organisation so that the results are seen as a true and unbiased assessment of the scheme. This is particularly so for an ITS scheme that is highly innovative or which has a high public profile, such as the congestion charge scheme in Stockholm.

Monitoring and evaluation are not carried out for their own sake – they are not ends in themselves. ITS projects cover a wide diversity and involve considerable investment of financial and other resources by stakeholder organisations. A formal evaluation is important in order to check that the expected value of an investment has been realised, and to determine who benefits and how those benefits compare with expectations. Evaluation is never simply a matter of “justifying” investment. It provides information which:

Evaluation makes it possible to assess the impacts which the scheme has had on stakeholders (such as travellers and operators) – and on a range of policy objectives such as the environment, safety, sustainability and efficiency. The stakeholder perspective for minority groups who may be disproportionately affected – positively or negatively – will be important, for example people with a disability or vulnerable road users, such as pedestrians and cyclists.

Organisations that fail to undertake full and proper evaluations of their ITS deployments are at a disadvantage when trying to justify proposals for further investments in the future. This applies whether the organisation is a public authority trying to determine the direction of future transport policies, a road operator considering its investment priorities or a commercial organisation that sees new business opportunities. A well-planned and documented evaluation of an existing scheme, helps justify and gain support for the next one.

The type of evaluation to be undertaken is determined by the evaluation objectives. They may include:

Stakeholders involved in commissioning an evaluation of ITS can include policy makers at national or local level, road or transport authorities, transport operators and users, and the organisations directly involved in Road Network Operations. Depending on the scale and complexity of the evaluation - it may be carried out in-house or by specialist consultants or university researchers.

The involvement of Road Network Operators in the evaluation of ITS for Road Network Operations includes:

Road network operators and public road authorities often find it difficult to make a business case for ITS. Evaluation results can support this process. The US DOT’s ePrimer’s Module 12 discusses how to make the business case.

Evaluation of an ITS deployment can help make the business case for investment by:

Public Sources of Evaluation Results

Evaluation results for ITS schemes have been compiled and consolidated in several resources. Some are databases which can be searched for results relating to specific types of scheme or meeting particular objectives. These are invaluable in helping identify expected impacts and potential performance measures. They also demonstrate the advantages of reporting evaluation results using a common framework – to compare studies which may have been carried out in different countries and with different requirements for evaluation and reporting. Sources of ITS evaluation results include:

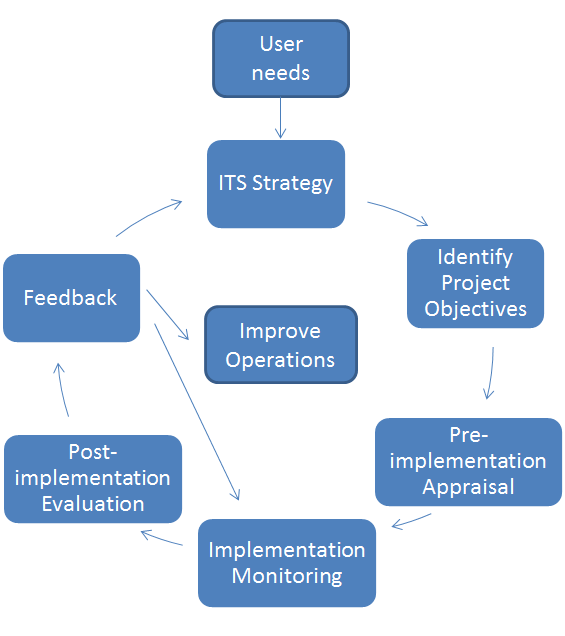

The evaluation cycle uses the principles and values that underpin the development of any community – those of Learning, Evaluation and Planning (LEAP), which are often summarised as: analyse – plan – do – review. The evaluation process is cyclical – positive results can be built on, and less positive results can be analysed to determine what went wrong, what can be done to remedy the situation – and what can be done to improve the results of similar applications in the future. This cycle is illustrated below and shows that evaluation is a key part of the process of implementing ITS. It is not an optional ‘extra’. The diagram shows how monitoring and evaluation can provide both short-term feedback to improve current operations and also results that will feed into the ITS development and investment strategy.

The ITS evaluation cycle

After deployment, post-implementation monitoring and evaluation of an ITS scheme is used to assess whether the system – as installed and operated – is meeting project objectives, delivering the expected performance and matching user requirements (which themselves may change over time). ‘User needs’ are not necessarily those of the driver of a vehicle. They might be the needs of the road authority or network operator to improve system performance and deliver better safety or traffic flow, the needs of the environment, the needs of the wider integrated transport network – or the needs of the communities affected by other people’s travel.

The results of post-implementation analysis should be fed into the evaluation cycle, improving operations and monitoring – and influencing ITS strategies for the future. The feedback provided by the evaluation informs future investments and their design. If the ITS is not performing as expected, feedback can help in understanding how to adjust or adapt the scheme.

Automatic Fare Collection, Turkey

In Izmir, Turkey, the information generated by the automatic fare collection and real time bus information system is being used to re-design the route network, with planned interchanges and improved service quality. It has led to significant increases in passenger numbers. See World Bank Case Study: Izmir, Turkey

A carefully constructed evaluation plan is key to this cyclical process and is an essential part of any programme for developing ITS. (See Evaluation Plan)

Evaluation is significant for any ITS deployment, but especially for a scheme which is innovative or deployed into a new situation. It shows the contribution that the scheme can make to meeting transport policy and everyday operational objectives, and can be used to improve and fine tune ITS operations –providing feedback for subsequent rounds of deployment. Without an adequate evaluation, organisations cannot be certain that they have obtained the properly functioning scheme for which they have paid. Evaluation results can also be used to inform future ITS policy and strategy. (See Improving Performance)

Another use of feedback from ITS evaluation is to improve the process of appraisal prior to deployment of a future scheme. (See Project Appraisal) The results of real life evaluation impacts – which include the costs of building, maintaining and operating ITS schemes and the benefits achieved – can be used in future investment decisions, to make sure that systems selected meet specific user requirements.

Road network operators have an important role throughout the evaluation cycle. They are involved in developing the operating strategies for their networks, identifying ITS project objectives, pre-implementation analysis to inform investment decisions, scheme selection and analysis of user requirements. As scheme ‘owners’ they gather monitoring data during implementations of ITS. Increasingly, ITS includes features that provide the basis for monitoring patterns of traffic demand and the behaviour of road users. (See Network Monitoring) Road network monitoring data is used by operators for pre-implementation analysis and for monitoring traffic, safety, incidents and other performance criteria on the network – after an ITS implementation has been deployed. It provides vital input to the evaluation. Road network operators will often commission independent evaluation and use the results to feed back into future strategies and investment decisions. (See Operational Activities)

Monitoring in conjunction with evaluation is used to learn lessons and improve future performance. It addresses issues such as: does the ITS meet the objectives and are the outcomes as intended? It can identify the range of benefits achieved which can then be quantified with data from internal monitoring. Careful monitoring of costs helps identify the operational and maintenance costs for a specific service – which can be separated from wider organisational costs.

The performance of the relevant elements of the transport system should be monitored to provide the benchmark against which the added value of the ITS scheme is measured. Performance monitoring can be used to improve operation of the ITS, provide data on the impacts and benefits and demonstrate whether the anticipated benefits and impacts have been realised.

The focus of the monitoring activity is likely to vary with the scale and maturity of ITS deployment. For example, for an area where ITS is relatively new and the number of applications is limited – such as cooperative driving based on Vehicle-to-Vehicle (V2V) communications – monitoring is likely to focus in depth on the performance of individual applications. Where deployment is extensive – such as electronic payment or non-stop tolling – the main focus is likely to be on monitoring the overall presence and performance of ITS in the transport system at a strategic level – in addition to the individual applications. These different approaches have different evaluation requirements.

For example, the US Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) has taken a strategic view of progress with ITS deployment through the use of “a few good measures” that are monitored each year. This is illustrated by its “Intelligent Transportation Systems Benefits": 1999 Update”.

The performance criteria defined in the evaluation plan (See Evaluation Plan) should be monitored both before and after implementation. Depending on the ITS implementation, it may be necessary to monitor ‘control’ sites as well as the implementation site.

Performance monitoring covers the services delivered as well as the technologies used. It involves:

Indicators should be selected which are easy to understand and measure, and are clearly linked to the performance requirements and objectives of the scheme. Where possible they should be common indicators, which can be used across a variety of schemes. (See Indicators)

Where possible, the ITS scheme should be designed so that it automatically provides data for performance monitoring. For example:

Monitoring and evaluation are key elements for a learning organisation. An important part of the evaluation cycle is to feedback results from evaluation to inform ITS strategy, ITS operations and the requirement for monitoring. (See Performance Measures)

At a strategic level, the results of monitoring and evaluation can be used to:

Evaluation results are also used as feedback to improve operations and monitoring – for example to optimise performance of the ITS during day-to-day operations. The ITS will often need to be adjusted on the basis of evaluation results in the early stages of operation. These adjustments should increase acceptance of the ITS by travellers operators and other users. Even if evaluation results show the system to be working well, there may be scope to optimise it further. Any adjustments made in the early stages, after implementation, will need to be recorded carefully so that they can be taken into account in the evaluation. The full scale evaluation should be carried out after adjustments have been made and the system has ‘settled down’ – and its effects have stabilised.

Monitoring Automatic Vehicle Location of Buses in South Africa

In South Africa, monitoring of an automatic vehicle location ITS application for buses, identified issues of communication over the mobile network operator’s network – which reduced the performance of the automatic vehicle monitoring system. This was found to be a result of the mobile network operator changing the communications protocols without considering the needs of the public transport operator. An agreement has been reached between the two parties – whereby the mobile network operator:

The monitoring also highlighted potential impacts on the service level agreement – affecting the suppliers of other components of the system – which had not been anticipated when the service was planned. Further information: See World Bank Case Study Johannesburg, South Africa

Monitoring data can be used to assess the extent to which the ITS meets operational requirements, for example, by:

Performance measures can be used to define payments in contracts – to provide incentives for meeting performance targets and to provide the basis for penalty charges if targets are not met. Where payments for completed work depend on meeting performance targets, specialist advice on risk management and performance measurement is suggested.

Performance Measures and Payments in Dublin

In Dublin, the bus company has a Public Service Obligation Contract with the National Transport Authority. Performance measures are linked to payments. The automatic vehicle location and real time information for bus services provides data on performance which is used to resolve operational issues. For example, running times have been reported as a problem by drivers on some routes. The monitoring data can then be used to analyse whether there is real problem which occurs at specific times of day or days of the week, occasional or frequent – so adjustments can be made. Further information: See World Bank Case Study Dublin Ireland

Performance measures can be also used to look towards the future. They can, for instance, define targets for improved performance as part of a process of continuous improvement. More widely, they can be used to provide recommendations for future operations.

Funding programmes may have put in place established processes for monitoring and reporting performance to obtain approval for payment. For example the Asian Development Bank has ‘Guidelines for Preparing Performance Evaluation Reports for Public Sector Operations’.

Monitoring and evaluation data can be used to assess operational effectiveness – identifying whether the ITS is readily incorporated into day-to-day operations and whether there are additional training needs in an organisation. This is one of the aspects addressed in a World Bank Case Study on monitoring and evaluating ITS for automatic bus location, bus scheduling and real time information.See World Bank Case Study Mysore, India

The US DOT’s ePrimer discusses organisational capabilities and refers to work by AASHTO in the US that provides guidance on how to evaluate capabilities and prepare an action plan. This includes capabilities for performance measurement.(See ePrimer Module 12)

Evaluation results also improve the quality of appraisals carried out before investment decisions are taken (See Project Appraisal) – by providing feedback on the performance of ITS options – such as, what did they achieve, what impacts did they have on user demand and the use of other modes. Useful tools are databases and websites which bring together evaluation results from a range of applications in different areas and contexts. This emphasises the value of reporting results and making them widely available.

Before beginning to plan an evaluation, the reasons for doing it and the uses which will be made of the results should be clearly defined. Understanding how those using the results will judge the success of failure of a scheme is an important first step in planning an evaluation. It is not sufficient to carry out an evaluation just because it is required in an organisation. An evaluation that is not properly planned may not measure what is considered to be important, and may even fail to measure the changes brought about by the ITS.

There are political aspects to evaluation, given the diversity of users and their needs. ITS can be adapted to serve widely different policy objectives. The key criteria for decision makers are generally that an ITS scheme must be, and must be seen to be:

A project evaluation can inform all of these aspects. If ITS can bring about a change which serves the needs of travellers, residents and road network operators within an affordable budget, then ITS will serve the public and decision makers alike. For instance in assessing whether an ITS project is:

The interests of the various stakeholder groups involved in the ITS should be considered before starting an evaluation:

Each of these factors should inform the evaluation design. An evaluation which takes them into account and involves stakeholders in the process, will have a much greater chance of producing results which are acceptable to stakeholders. This may mean devoting effort to informing stakeholder groups (including policy-makers) about the scheme – and the reasons for undertaking a thorough independent evaluation, to which their contribution will be key.

At the same time, it is important to remember that one of the key principles in producing a credible evaluation, is that it should be independent. In other words the results are balanced, not biased in favour of the interests of any stakeholder group(s).

To ensure a successful evaluation it is important to agree, at an early stage, clear roles and responsibilities between the various stakeholders involved in evaluation (whether as users of the results or contributors to the study).

Ethical issues need to be considered when planning how to carry out an evaluation and the methods to use. The evaluation should be designed so that there is no risk to, or other adverse impact on, users and stakeholders. Those carrying out evaluation studies have a responsibility to ensure that participants (such as users or employees) are informed of the purpose of any surveys (or other means of data collection) – and how the data will be used. Processes need to be put in place to ensure anonymity and security of data – including for data that is collected automatically (such as from automatic licence plate recognition techniques or CCTV cameras). Some organisations undertaking evaluations will be required, as part of their quality management, to present their plans and methods to an ethics committee for approval prior to starting the evaluation.

A variety of techniques exist for measuring impacts. The effort put into an evaluation will depend on the scale, location and objectives of the ITS scheme. A full-scale evaluation, on a scientific basis, is appropriate for innovative ITS where there is little or no published evidence on its costs, benefits and impacts. An ITS application which has been well proven may justify a simpler or smaller scale evaluation. The scale should be agreed by the stakeholders involved at the outset. Considerations include the:

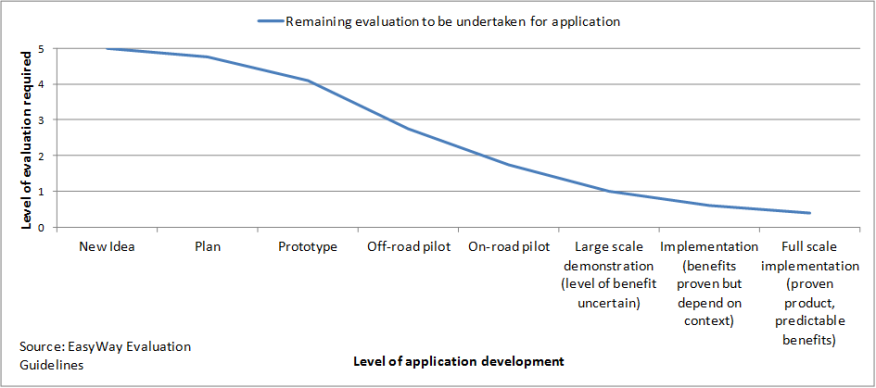

Over the lifecycle of an ITS application – from concept through initial pilots to larger scale demonstrations and full scale deployment – the extent and coverage of the evaluation needed, reduces. This is because full scale deployment only occurs after a considerable amount of evaluation has been undertaken already on prototypes, pilots and demonstrations – providing a good level of understanding of the ITS application. The European EasyWay programme illustrated this with a graph indicating how the level of evaluation work changes between stages of ITS development.

Level of evaluation required at different stages of application development. Source: Tarry S, Turvey S and Pyne M 2012. EasyWay Project Evaluation Guidelines. Version 4.0, p 8. EasyWay

EasyWay Programme and Projects (2007-2020)

EasyWay (2007-2020) is a major European Union (EU) programme focusing on the deployment of Intelligent Transport Systems (ITS) on the major road networks across Europe. It involves 30 European countries, bringing together road authorities and road operators – and their major ITS technology partners such as the automotive industry, telecommunications and travel service operators and public transport stakeholders. It addresses EU transport objectives: to improve safety, reduce congestion and negative environmental impacts, and promote the continuity of services at through coordinated deployment of real-time information, traffic management and freight and logistics services.

When planning an evaluation, it is important to consider the following aspects:

In preparing an evaluation plan(See Evaluation Plan), it is helpful to draw up a detailed checklist which is specific to the scheme being evaluated. This ensures that the relevant costs, benefits and impacts are identified and assessed. (See Improving Performance)

Several toolkits are available that provide guidance and examples for road network operators and others, supporting activities in different stages of the evaluation cycle – including:

The Netherlands assessed and summarised the key principles of the main techniques used in evaluating ITS in 2003 – with reference to ITS implementations on inter-urban routes.

The UK’s Department for Transport’s ITS Toolkit is designed to make it easier to specify and procure ITS. It includes guidance on how local authorities can benefit from evaluation results.

An overview of the toolkit is contained in the: Traffic Advisory Unit, Understanding the Costs and Benefits of ITS: A Toolkit Approach, Leaflet ITS 1-06, UK Department for Transport, 2006.

Finland’s guidelines are based on a national framework for project appraisal – which is published in English. They cover both project appraisal (pre- implementation) and project evaluation (post-implementation) – and include checklists of possible impacts, lists of indicators and measurement methods, and checklists for evaluating different aspects of schemes. Four examples are given of how the guidelines have been applied to specific projects.

The EasyWay Handbook is aimed at European Road Network Operators and others concerned with evaluating ITS on inter-urban roads in Europe. It discusses the evaluation cycle and includes examples of feedback mechanisms showing how ITS project evaluation is used by decision-makers. See EU ITS Portal

These guidelines are designed for pilots and demonstrations of new transport schemes in Europe. They provide guidance through all stages of the evaluation cycle.

The 2DECIDE ITS Toolkit is an on-line decision support tool to assist transport organisations, network operators and authorities in selecting and deploying ITS. Users can query the database for ITS solutions relevant to a specific context, problem, goal or ITS service. They receive information back on relevant services with an indication of the impacts which may be expected in a specific context. It includes a database of costs, case studies and evaluation reports. To access the toolkit you must first set up an account (free of charge).

This handbook on planning and organising Field Operational Tests (FOTs) of ITS technologies includes guidance on experimental design, data analysis and modelling socio-economic impacts and how to carry out an assessment. Although it is aimed primarily at trials of driver assistance systems, the principles apply equally to other ITS.

FESTA Socio-economic impact assessment for driver assistance systems (Field Operational Tests Networking and Methodology Promotion) - Europe

This supplements the FESTA Handbook and provides advice on the methodology for socio-economic evaluation of Field Operational Tests (FOTs) of ITS. It covers the assessment framework, stakeholders, scope of assessment, analysis methods, financial analysis and data needs. Although it is aimed primarily at trials of driver assistance systems, the principles apply equally to other ITS.

The US Department of Transportation’s ITS Knowledge Resource is a website which provides information on the benefits, costs, deployment levels and lessons learned – from ITS deployments and operations. The information has been assembled from summaries of real life examples starting from the late 1990s. The database supports informed decision making on ITS investments by tracking the effectiveness of systems which have been deployed, over time. Users can search the database, filtering by type of application and country or US state in which it has been evaluated.

The World Bank provides brief guidance on pre-implementation performance criteria, post-implementation monitoring and evaluation. A series of case studies provide examples of urban ITS implementations. The extent to which they have been evaluated is described. The case studies cover both developing and developed economies. They show that few transport organisations carry out comprehensive evaluation of ITS – which makes it more difficult to obtain support for future schemes.

The World Bank has produced a technical note ‘Independent Evaluation: Principles, Guidelines and Good Practice’. It is aimed at global and regional partnership programmes carrying out independent evaluation. It provides guidance on the principles and purpose of independent evaluation, its conduct and the form of evaluation, developing performance indicators – and key evaluation issues. Although not specifically designed for ITS schemes, the principles apply to any evaluation project.

The International Benefit, Evaluation and Cost Working Group IBEC has produced international training materials on international experience in Intelligent Transport Systems in the form of ‘Evaluation 101’ presentations by experts in ITS evaluation.

The Victoria Transport Policy Institute has published many documents on different aspects of transport evaluation. Topics include: cost and benefit analysis, multi-modal transport evaluation, evaluating the safety impacts of mobility management strategies, evaluation of energy saving and emissions reduction strategies, developing indicators for specific objectives and evaluating research quality. It also provides a critique of a bad evaluation study.

There are practical aspects which should be considered before starting an evaluation. In addition to the overall budget for implementing the ITS scheme, a budget should be allocated to evaluation – which will involve work before and after implementation. In some cases this will be considered as part of the implementation. In other cases the evaluation budget will be treated separately. In either case, the evaluation budget represents an investment in planning for future projects. It is important to consider:

The evaluation should focus on measuring the key aspect that the scheme is planning to change – not to pick up some general statistics or ‘feel good’ measures that may bear no relation to the effect of the ITS. For example, an evaluation of a real-time journey time information service which just asks users whether the ITS has had an impact on the quality of their journeys will only provide an indication of user satisfaction. Unless traffic flows and journey times are measured on the main route and alternative routes when incidents occur – the evaluation will not be able to determine the extent to which the ITS reduces the impact of incidents by spreading out traffic onto alternative routes. Nor will it be able to identify any detrimental effects to other roads, caused by diverted traffic.

Where possible, the ITS should be programmed to provide data which can be used to monitor its impacts. For example, real-time information at bus stops provides information on bus headways. Storing this data gives a record of intervals between bus services, which, for passengers, is a key aspect of reliability. In the case study on demand responsive transport in Prince William County USA, the service data was used to monitor performance automatically, reducing the cost of data collection and analysis. (See ITS for Demand Responsive Transport Operation, Prince William County USA)

Specific stakeholder groups may have particular requirements from a scheme – which influences the methods of evaluation, the budget, timing and scale of evaluation. It is important to understand these requirements and constraints at an early stage in planning the evaluation to determine to what extent they are met. The evaluation should be designed so that it is possible to identify how the benefits and costs of the ITS are distributed between the different stakeholders – who gains and who loses.

For example, as well as evaluating the impacts of ITS on the travelling public (the ‘end’ users), evaluation should consider the requirements of the operators and other staff of the organisations involved in delivering the ITS. These impacts can be evaluated by interviewing staff – and in some cases by using data on work patterns and completed tasks.

An evaluation of the impacts of teleworking on travel patterns in Hampshire not only evaluated the impacts on the employees concerned, but also included a survey of managers and colleagues to assess the impact on working patterns and productivity of the organisations for which the employees worked. Transport Research Laboratory, Transportation Research Group (Southampton University) and University of Portsmouth. 1999. Monitoring and evaluation of a teleworking trial in Hampshire. TRL Report 414. Transport Research Laboratory, Crowthorne.

An evaluation of cross-border traffic management strategies in The Netherlands included interviews with employees which identified ways in which the processes for implementing the strategies could be streamlined. Taale, H. 2003. Evaluation of Intelligent Transport Systems in The Netherlands. Transportation Research Board Annual Meeting, 2003. Washington DC.

Evaluation is specialist work. Some road network operators, road authorities and other organisations tasked with implementing ITS have limited capabilities within their organisation for monitoring and evaluation of ITS. However evaluation is not always complicated, and does not always have to be carried out by specialists. If there is a need to collect data, this can be done in-house, provided that it is done credibly using an objective approach and sound methods.

For most evaluations it is a good idea to use specialists the first time one is undertaken – so in-house staff can learn how it should be done. Formal training should also be given to enhance the learning experience. It is also worth employing specialists from time to time afterwards so that up-to-date methods can be introduced to in-house staff. In some circumstances it will be important that the evaluation is carried out by an independent organisation – to ensure that the results are credible (for example, in reporting back to funding agencies).

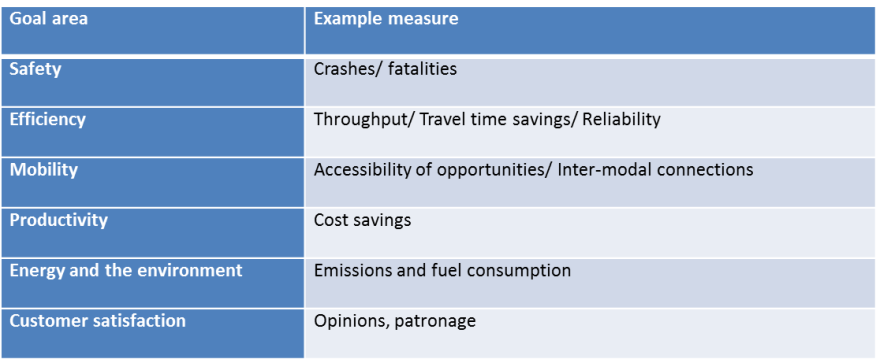

Affordability is often an issue. Whichever evaluation method is used, there may be insufficient budget to answer all questions related to the ITS. It then becomes necessary to decide which aspects of the evaluation have the highest priority. A Critical Factors Analysis can be useful at this stage. It looks at the different goals that a scheme is expected to address – and the key indicators needed to measure the extent to which they have been achieved. This is illustrated in the figure below.

Template for Critical Factors Analysis

Evaluation management includes planning and monitoring the work of evaluation to ensure its technical quality, cost-effectiveness and timeliness. Key elements in managing a successful evaluation are:

Information is a key element of ITS. ITS applications collect, combine, store and communicate data about the transport network, its users – and the stakeholders involved in providing services. In addition to operational data, monitoring and evaluation also requires data collection on individuals and organisations, their views and responses to the ITS. This can raise concerns about privacy. (See Legal and Regulatory Issues)

Those involved in planning, conducting and reporting on evaluation and monitoring activities need to ensure that data protection and privacy issues are considered and addressed – and that any requirements of data protection legislation are met. The US DOT’s ePrimer discusses data protection for ITS at some length and sets out strategies for mitigating privacy issues – which apply to monitoring and evaluation as well as operational data:

External Funding agencies are likely to have specific requirements which must be met by evaluation work, in addition to following best practice in designing and carrying out evaluations. These might relate, for instance to:

Evaluation results from other schemes are helpful when planning an evaluation. They may:

Care needs to be taken when considering the methods used and results obtained from elsewhere. The number of case studies of ITS evaluations in developing economies is limited and the temptation will be to look at results from developed economies which are more numerous and readily available – but they may not be appropriate to the context. User reactions and benefit valuation contexts can differ widely between different countries and regions with different social and economic profiles. The key issue to be addressed is whether the planned scheme is similar to the case studies in terms of its context, objectives and user base?

ITS evaluation must be well thought through and properly targeted if it is going to be useful. The methodology should take into account: the ITS scheme objectives, user needs and stakeholder expectations. It should make use of quantified and qualitative measures that match the needs of decision-makers.

At an ‘overview’ level, the evaluation should identify both the impacts that were planned and the unintended impacts – establishing qualitatively the nature of the changes which have occurred and their possible causes. At a more detailed level, the evaluation should quantify the changes after the scheme is implemented, assess the scale of those changes and the level of confidence in them – and identify the mechanisms leading to significant changes. (See Guidelines and Techniques)

A systematic approach is needed for the monitoring stage of the evaluation cycle to ensure that different types of impacts (benefits, disbenefits and costs) are identified and measured. Developing an “Evaluation Plan” is key to this. It is a technical document – separate to an “Evaluation Management Plan” which covers resources, timing, coordination with other activities, and data management. (See Evaluation Methods)

The evaluation plan should be drafted and agreed before the scheme is implemented, so that the data needed to measure the situation prior to the deployment can be defined and collected in advance. The time frame available for collecting ‘before’ data may also influence the timing of some of the ‘after’ data collection needed for comparative purposes.

Consider the ‘Checklist’ of issues that need to be addressed when preparing an evaluation plan. (See Evaluation Methods) Useful input may come from the evaluation plans used for other studies – or other guidelines – in determining all the elements that need to be addressed.

An evaluation plan needs to be well specified:

Focus on identifying the policy objectives that the ITS scheme is intended to address and assess the extent to which it contributes to reaching those objectives.

Define the ‘base case’ or ‘before’ ITS deployment situation – to enable comparisons with the ‘after’ deployment situation.

Define the area to be covered by the evaluation. A map is helpful.

Define the timing and duration of the evaluation – both before and after deployment. Ensure that the timing minimises external effects (such as seasonal effects). Ensure that the duration is long enough for the full impacts to be identified – not just the initial effects whilst users are adjusting to the ITS deployment.

List the impacts expected, using information from other schemes, preliminary investigations and the scheme appraisal. In some cases it may be possible to list the expected impacts in quantitative terms – but if there is no evidence of impacts from previous schemes, a qualitative description of expected impacts will be needed. Evaluation toolkits and databases of evaluation results are useful sources. (See Improving Performance)

Prepare a table listing the objectives, the indicators for assessing them and the data sources for the indicators. (See Evaluation Methods)

Define the evaluation methods to be used. Consider using more than one approach to provide a more ‘rounded’ view of the impacts and to confirm conclusions. (See Evaluation Methods) In the case of a complex evaluation, draw a ‘flow chart’ showing how all of the different sources of information fit together to inform the evaluation objectives.

Consider the experimental design principles to be used. For example compare the performance of a package of ITS measures with a ‘control’ that is as similar as possible but has no ITS element. It is desirable to make comparisons using more than one location to take account of other variables.

Ensure that the design will capture any unintended side effects of the ITS measures as well as the expected impacts. Review the results of other studies to improve the design.

Define the details of the data to be gathered – before and after implementation – to inform each of the indicators. Include, for each indicator, information on sample sizes, statistical confidence, timing, and location sites.

Review how external factors could influence the evaluation and plan the evaluation to exclude them. For example, changes in the transport network of a neighbouring area could have knock-on effects in the area in which the ITS is to be deployed. Wider scale changes such as growth in vehicle ownership or a downturn in the economy will influence the demand for transport and could ‘confound’ the evaluation.

List the performance criteria which can be used to assess the monitoring and evaluation. These can be included in the supply contract for commissioning the monitoring and evaluation.

The following key principles are useful to follow in reporting the results of monitoring and evaluation.

Consider the audience for the results. Separate reports may be useful for different stakeholders. Policy makers may require an overview of results and a summary of the implications. Practitioners may benefit from a more detailed technical report. It may be appropriate to develop an information leaflet, web page or news article to summarise some of the main impacts of the ITS for the general public.

Make sure that the results are reported in a transparent way, easy to understand and easy to compare with other studies. Include details of the statistical confidence in quantitative results – where this is appropriate. Provide background supporting information about the context of the scheme (perhaps include references to other sources for further background information) to help users transfer the results to other contexts.

Include both positive and negative impacts to provide a balanced report. Ensure that both qualitative and quantitative impacts are reported – and avoid giving the impression that more value is placed on indicators than can be readily be quantified. For example, some impacts can be converted into monetary values and combined with others to provide an overall ratio of costs to benefits. This will not be possible for all indicators – but those that cannot be measured in this way should also be reported. Frameworks such as ‘planning balance sheet’ and ‘multi-criteria analysis’ can be used to summarise results.

Make the results widely available so that decision makers and practitioners elsewhere can learn from them. This will help to build a knowledge base for evaluating ITS and help to reduce the time and effort involved in planning, implementing and evaluating other schemes.

Results can be published through journals, presentations at conferences, webinars, or by submitting reports to web sites that publish case study. Potential platforms include the:

The following topics are useful to cover in any technical report of evaluation results (which may also include further information as appendices:

Sources of guidance on evaluation planning and reporting.

There are several sources of guidance on writing evaluation plans and reporting results:

Indicators for measuring the success of an ITS scheme are directly linked to the objectives that it is aiming to achieve. ITS, like any other investment, should contribute towards solving a problem or delivering a vision. The measure of success is how far the problem is solved or the vision delivered within the available budget. It is important to define indicators which can be used to measure whether the ITS scheme has met its objectives.

Template for Critical Factors Analysis

The template above for Critical Factors Analysis shows how measures (or indicators) are linked to goals. The same approach can be used for establishing indicators to evaluate the extent to which objectives are met. It provides a systematic way of expressing the outcomes being sought and the visible results or measures expected – if the ITS has the desired effect. These outcomes will not necessarily be entirely within the public sector, as the example above – of efficiency measures, shows. An evaluation may include indicators measuring the extent to which private sector objectives are met, as well as the extent to which public sector objectives are met.

This approach can be applied to the full range of objectives for ITS. In addition to those illustrated above, safety improvements might include benefits – such as, perceptions of personal safety. Environmental benefits will often include noise reduction and might include community benefits – such as a more pleasant neighbourhood. Efficiency benefits can go beyond the supply-side measure of traffic flow or throughput – to efficiency gains for industry from access to information, knowledge and control over fleet movements. In each of these cases, it is possible to define a ‘goal area’ or ‘outcome’ and to agree the ‘measures’ by which progress can be monitored.

At the more detailed evaluation planning stage, this sort of table can also be used to summarise the sources of data which will be used to provide evidence on the indictors. (See Monitoring)

Where possible, indicators should be based on commonly used measures, so that evaluation results can be compared between schemes. For example network performance may be measured using indicators such as change in journey times at peak hours and change in variability of travel time. If there are agreed definitions of these at a national level – or within a road authority – it will be easy to compare the outcomes of different schemes aimed at improving network performance.

Indicators must be defined in quantifiable terms. In evaluating ITS, many of the indicators used are quantified measures. For example, an indicator for the impact on safety is the number of road accident fatalities – which can be measured from accident records. Another important indicator may be the impact on users’ perceptions of safety. This is a qualitative measure but it can be quantified in various ways. Examples include: asking users to compare safety before and after using a 5-point/7-point rating system – and measuring the proportion of users who say they think a system is safe, or measuring the proportion who say they think safety has improved.

It is helpful to review other evaluation projects when deciding on the indicators to be used. They may help identify common indicators that have been used nationally or even internationally in comparing scheme results. They will also help inform which indicators are most suitable for measuring performance against different types of objective – and potential sources of data for each indicator.

A critique of an evaluation of transport performance in Canada provides an example of some of the pitfalls involved in defining and using indicators. Of the 23 indicators used, a few were found to be appropriate and widely used, some were found to be ambiguous and biased – and others were found to be illogical. The ways in which comparisons were made between areas was considered inappropriate due to geographic, demographic and economic differences.

Evaluation guidelines are also a useful source of indicators:

Appendix 1 of these guidelines proposes performance indicators. Those considered particularly useful are highlighted – and suggestions for indicators aimed primarily at private sector and public sector objectives are identified. See EU ITS Portal

Indicators for evaluation include:

This project developed performance indicators for evaluating traffic efficiency, traffic safety, emissions reduction, social inclusion and land use. The indicators are targeted at urban schemes and were developed in consultation with 16 cities across Europe. The project report discusses the principles behind performance measures and the process of developing them. It presents an evaluation framework and provides guidelines for applying it.

The UK Department for Transport’ guidance on transport analysis includes detailed information on indicators for scheme costs and user and provider impacts.

The benefits and costs databases provide information on the indicators which have been used to evaluate a wide range of ITS deployments .

The case studies in the UK’s Department for Transport’s ITS Toolkit include examples of indicators used to evaluate schemes.

During the lifecycle of any ITS deployment or a field trial – the most appropriate evaluation method will vary:

The Code of Practice for the Design and Evaluation of Advanced Driver Assistance Systems – developed for evaluating prototype is an example of a checklist for concept development and prototypes. See Advanced Driver Assistance Systems

Simulation and modelling are relevant to project appraisal. (See Project Appraisal)

The FESTA handbook provides information on planning and organising Field Operational Tests (or trials) of driver assistance systems. Many of the principles apply equally to other ITS.

Guidelines on evaluation methods for ITS have been produced in several countries and are available in English:

The World Bank provides guidance on monitoring and evaluation methods with information identifying the usefulness of each technique, advantages and disadvantages, costs, skills and time required – and sources of further information. See World Bank Report on Monitoring and Evaluation

The World Bank also provides a guidance resource on how to design influential evaluations. See Influential Evaluations

Many techniques are used in road network evaluation. Several are also suitable at the appraisal stage when planning ITS investments. See Project Appraisal There are a wide variety of approaches:

ITS is often deployed simply because it is obvious.

Where there is a large body of consistent evidence showing that a particular type of investment is value for money, it makes sense to go ahead and implement it, rather than commission further studies. Multi-criteria analysis can be used to double check the gut instinct or help explain the ‘common sense’ to decision makers.

If a road junction is very congested, it is possible to deduce that traffic signals will improve the flow without carrying out a large traffic modelling exercise. Other implementations will provide predictability on costs. The World Bank Case Study on ITS implemented at Dublin Bus is an example of where it was reasonable to rely on common sense. The perceived benefits were reported but not quantified because it was not considered necessary to do so. See World Bank Case Study Dublin, Ireland

The best source will be systems which have consistently proved to deliver value for money. The US DOT and the European 2Decide projects and toolkit provide online databases of ITS costs, benefits and lessons learned from ITS schemes.

Very expensive systems will often need an evaluation, even if it is only a ‘Critical Factors Analysis’. New ITS schemes should always be evaluated because there is no body of evidence to demonstrate value for money. ITS which have different impacts in different circumstances should also be evaluated in the different contexts.

Qualitative methods raise standards and provide benchmarking when planning and evaluating ITS investments.

The methods include focus groups (also known as group discussions), user panels, citizen panels and quality circles. They involve structured discussions between stakeholders which are mediated by an independent facilitator.

These methods provide a source of information for planning investments and reviewing impacts and implications – in a way that takes account of the views of all relevant stakeholders.

Transport consultants, social research companies and market research companies.

Care needs to be taken to ensure proper representation of all relevant stakeholders – and that members of focus groups and panels are able to contribute on an equal basis. These techniques complement quantitative investigations – and are not a substitute for them.

These provide statistical information on road users’ and travellers’ journeys and patterns of movement.

Methods include:

Travel surveys provide an input to traffic models and are a source of travel data for planning ITS services and analysing changes in response to those services.

Transport consultants, social research companies and market research companies.

Poor survey design, weak fieldwork techniques and low response rates can all affect the statistical accuracy and reliability of any survey – and make the results misleading. Quality controls and consistency of survey methods are particularly important for ‘before’ and ‘after’ surveys.

This is the basis for most cost-benefit analysis. It assesses what people will do in response to ITS.

It is a very basic method which looks at the ‘costs’ of journeys before and after the ITS implementation and predicts changes in behaviour on the basis of past responses to changes in costs.

To make rough estimates of response to ITS where the application is fairly common sense, but needs some additional quantitative support. It will be at the heart of any traffic model.

In-house economists or transport consultants.

Generalised cost is a simple concept which is relatively limited in what it describes. Generalised cost models only measure costs which can be calculated in monetary terms (for example standard monetary values of time). Monetary values are not available for some of the policies which ITS can deliver; and several of the policy objectives that ITS does address will show an increase in the generalised cost of travel, rather than a decrease. For instance, the aim of ITS will often be to change the variability in journey times - rather than reduce total travel time, or deliver other policy objectives such as reduced emissions.

Utility models try to simplify the presentation of what people gain from a change. They are closely related to generalised cost models, but are better designed to reflect user behaviour.

Statistical analysis is used to measure the ‘utility’ or ‘good’ that different people receive from a change.

When user behaviour is important to the outcome that the ITS is aiming to achieve – such as when the aim of an ITS scheme is to encourage people to change mode of travel from car to public transport.

Specialist transport consultants and university departments of statistics or economics. This is not a job for amateurs.

A good utility model is a very powerful tool. The form of the model is fundamentally simple but can become complex. Doubts about the ‘truth’ of these models arise because many use stated preference data to derive values – but historic data can be used instead.

Measure whether users have any perception of an impact that benefits them.

‘Before’ and ‘after’ surveys measure perceptions of the factors which the ITS is intended to address.

When the ITS scheme is intended to improve user comfort or community amenity.

Market research companies, social research companies, transport consultancies.

Many surveys use ‘Lickert scales’ to ask whether things are, for example:

Much worse / A little worse/ About the same/ A little better/ Much better’

The value of these is limited. Likert warned that the scale reflects attitudes – not absolute measurements. The surveys can result in unrealistically optimistic scores. It is not easy to design customer satisfaction surveys which yield valuable results. They are probably best used in conjunction with other methods such as measures of changes in behaviour associated with the impact of the scheme.

It measures how behaviour will change in response to ITS. The benefit of ‘stated preference’ is that it does not use past behaviour as a guide. Other transport models are ‘revealed preference’, using past responses to a change – to derive values for responses to future change.

It provides a rigorous assessment of the utility values of different elements of a product or service – based on trade-offs made by a respondent in a highly structured interview.

Where ITS is new, or where the transport policy which the ITS supports, is new.

Transport consultants, some market research companies.

The risks are that respondents will not make the same choices on paper that they will make in practice. The respondent may not see the barriers to using new ITS. The research may not describe the new product’s drawbacks, only its advantages. Some respondents may not be able to predict what they will do – for example in response to some developments in Information and Communications Technologies, people have relocate their homes further away from work, but would they have predicted that in a survey? The concern is that conjoint analysis will derive wrong answers whilst the nature of the answers (a value or number) will be precise – leading to wrong investment decisions.

It can be used to measure changes in factors such as traffic and travel time.

ITS create, collect and transmit data. These data can show the change in the targeted outcomes over time. Baseline ‘before’ data are needed for comparison with internal data obtained after deployment.

Use this in every case where it is technically feasible.

Design the measurement of the results into the ITS.

ITS will only measure quantitative results. Changes in factors such as user confidence cannot be measured, although they may be implied. Public transport patronage cannot usually be measured by ITS unless the application is a ticketing or revenue collection system.