The road authorities and other stakeholders involved in ITS services need to interface with stakeholders across the value chain. The success of the ITS service value chain hinges on successful cooperation between the different stakeholders and their functions in the chain. This is not restricted to public sector agencies only, but will also include private stakeholders. Today, it is also part of the role of Network Operators to enable and facilitate value-added service development.

The ITS Framework Plan and any ITS Architecture - are high-level reference documents which set the context for deployment. As ITS projects develop and services come on stream it is necessary to be claer about legal and institutional issues, operational requirements and other stakeholder issues. For example, where the roles of different actors in the information supply chain is unclear - they need to be defined.

The timing of a project will often be dictated by budgetary considerations, even for high-priority projects with large benefits. Sometimes projects will be delayed due to a shortage of personnel with the necessary skills. Political factors will also impact on the timetabling - and can include the public visibility of the project and the potential impact of the investment on users.

Public objection or misunderstanding can lead to ITS projects being abandoned. For example, road pricing or congestion charging has, until recently, run into difficulties in securing public acceptance for various political reasons. The early introduction of road pricing in Hong Kong in the 1980s raised public suspicion about the use of AVI for “big brother surveillance.” This can have an impact on the implementation timetable - it may, for instance, be advisable to give priority to those investments which will deliver the highest benefits at the lowest risks or those investments which will deliver benefits to a greater number of stakeholders.

It is a real challenge to acheive an appropriate level of co-ordination and to create synergy benefits between the different stakeholders without bureaucratic costs. Administrative procedures can be a real obstacle - for example, different administrative procedures in adjacent administrative areas may need to be harmonised. New safety arrangements, operational procedures or detailed local operating agreements may also need to be developed and implemented to deal effectively with new measures - such as the installation and maintenance of roadside detection equipment. This can also take valuable time

ITS operational requirements are frequently geared to an operations or control centre at the hub of the ITS service, for example:

For many specific ITS projects, there will be a lead agency - which will be the organisation most closely associated with promoting the proposed ITS investment or the delivery of the new ITS service. New business units will oftent need to be created to cut across the traditional lines of responsibility between agencies - this is because ITS technology both requires and offers, new and greater opportunities for integrated deployment and interagency working.

For data exchange there is a need to create supply chain contracts, codes of practice - and to respond to other requirements. The availability of public data and distribution channels needs to be regulated in a legal framework - which should define objectives and public and private sector responsibilities. Data publishing, and distribution policy and practice will also need to be resolved (free at point of use, added value services; intermodal/ inter-agency exchange). There may be other legal issues to be addressed as well - such as data confidentiality.

Resolving the institutional issues needs to proceed in parallel with the technical aspects of ITS project planning. The specific ITS development must be assessed for its feasibility and desirability in the local context - from both a technical and non-technical perspective. There is usually more than one way to implement an ITS project - for example:

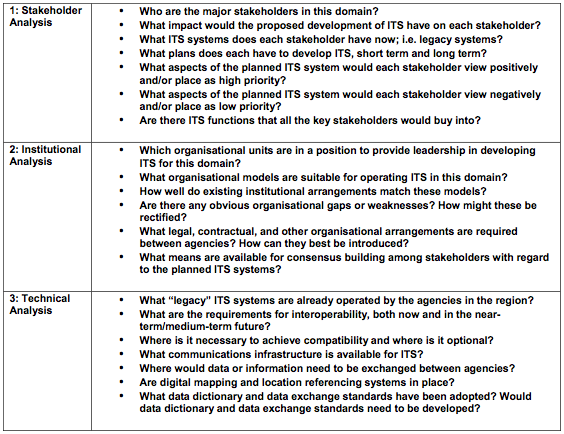

The type of implementation chosen will be governed by many factors. Some key inputs are listed in the figure below.

Figure 5. Checklist for use in developing a road map for ITS deployment

The ITS Road Map is a means of translating concepts and plans into reality. It assigns roles and responsibilities and specifies how stakeholders can organise themselves to implement the recommendations of the Framework Plan. The following is a checklist of topics which will need to be addressed:

Human Resources

Contractual and Legal Requirements

Effective dialogue between the main stakeholders is the key to transforming organisational arrangements from concept into reality. A task force of the major players can help to develop voluntary agreements and Memoranda Of Understanding (MOUs) on matters of common concern. For example, in Europe, MOUs on cross-border data exchange and on the provision of the language-independent Radio Data System / Traffic Message Channel (RDS/TMC) on FM radio were agreed in fora which provided the opportunity for all interested parties to work together to discuss problems and agree on practical solutions.

The body which is made responsible for the high-level coordination of ITS developmen must have sufficient standing to be able to influence the decisions of key stakeholders on issues such as conformance to ITS architecture, data exchange formats and the use of standards. A good example is the European ITS Directive (See ITS Directive) which determines the specifications which specific ITS services must follow for deployment in Europe. The roll-out of ITS services may also require voluntary cooperation agreements.

A national or regional steering committee with high-level political backing can be very effective in bringing together all the main stakeholders to focus on achieving a common goal. It requires the support of a dedicated interagency coordination unit or some kind of technical panel drawn from the participating authorities. International, national, and regional public/private partnership organisations - such as ITS America, ITS Canada, ITS Europe (ERTICO), ITS United Kingdom, ITS Australia, and ITS Japan (VERTIS) - can play a useful part in setting up this consultation machinery.

In parallel, at the national or regional level, it may also be useful to create an advisory panel of other major stakeholders in ITS - including any significant private-sector actors - for advisory purposes. The Minnesota Guidestar Program14 in the USA follows this practice. In Paris, there is the Consultative Committee on Road Information Broadcasting for service providers. In Japan, the VICS Coordinating Council, has responsibility for planning the VICS advanced traveller information system. In Europe, the ITS Advisory Group (See ITS Advisory Group), performs this role in relation to the ITS Action Plan and Directive.

Inter-agency and inter-company cooperation requirements may need to be formalised. Public/public, public/private, and private/private collaboration agreements and contracts are often needed. These agreements can range from informal agreements to cooperate on day-to-day operational tasks - to more ambitious and formal contracts and Memoranda of Understanding (MOU) which involve sharing of common systems. Midway between these two are the agreements on data exchange - specifying the agreed data formats and minimum data quality requirements (such as accuracy, timeliness, and extent of data consolidation or editing).

The contractual relationships and information flows involved in delivering ITS-based information services can be quite complex. For example, a private sector service provider may need to secure contracts at five levels:

Much of the groundwork will have been completed at the ITS Framework Plan stage. If the ITS architecture analysis has been planned effectively, the requirements for exchange and transmission of data, information, and other electronic transactions between agencies can be specified in fairly precise terms. This practice is recommended to ensure that the operational requirements of all the parties will be satisfied. The main steps are as follows:

It is likely that no two stakeholders will have precisely the same set of requirements - since each has individual needs and resources. If it is appropriate - the detailed requirements and responsibilities can be formalised in contracts or formal agreements - so that the receiving party can rely on a minimum performance specification from the provider, and there is a means of redress if this minimum is not achieved.

A good communication and public information strategy is very important - and needs to be kept up to date during project management. Neglecting the communication strategy and not implementing it in a timely way, can lead to the failure of projects - whilst paying proper attention to the communication strategy and its implementation can foster their success. In the 1990s a pioneer project in electronic payment, the Trondheim Toll ring, gained public support, partly because of the positive publicity it received. Similarly the original California Smart Corridor is another example of a successful project supported by an effective communication strategy. The outcomes might have been different - because of the number and the level of bodies involved - but all parties cooperated around a common mission.

Where possible, a Programme Manager should be appointed to bring communication, attention to detail, and energy - to overcome institutional problems. The Programme Manager can provide drive and co-ordination from project start through to deployment.