The context for deployment of ITS is the basic organisational, regulatory and institutional framework within which system development and service set-up take place. It will shape the environment within which the different ITS services are developed, deployed, operated and maintained. A well planned set-up which is accepted by all key stakeholders will improve the commercial and public sector business cases - with appropriate risk distribution, cost-sharing, service pricing and optimal quality delivery. (See Legal and Regulatory Issues)

In practice the context for deployment is constantly changing due to technological breakthroughs, and political, economic, environmental and demographic trends - which affect both the supply and the demand for ITS and other services. ITS deployment needs to be considered from a number of perspectives.

The market for ITS services, infrastructure and info-structure have been growing fast in areas such as navigation, tolling, driver support, telecommunications and digital mapping. The private sector, operating in the market, is constantly looking for a sound business case - in other words: sufficient revenue, return on investment and recovery of development and operating costs. Companies aim to build up demand for their services and products, increase the size of the market and their own share of the market - so their interests include:

The private sector will benefit from early knowledge of the public sector stakeholders' strategies and plans so they can respond appropriately to safeguard and advance their own interests. Companies follow closely, the development of markets, undertaking market research and analysis. They are usually able to make decisions and implement actions very quickly - often within a few months. This enables them to react to public sector strategic initiatives quickly - although planning processes do vary greatly amongst companies.

Road authorities and other public sector stakeholders plan their activities based on policy objectives and priorities. Some are directly transport-related such as road safety, congestion, traffic noise and emissions. Others arise from policy areas and objectives such as industrial competitiveness, climate change, energy sustainability and the information society.

Public sector planning usually involves three different time scales:

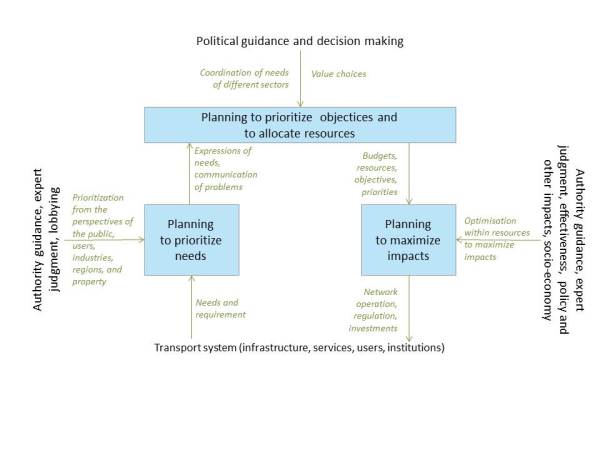

The planning processes, outlined in the figure below, includes the following stages:

To facilitate planning, public authorities need to create a framework for the socio-economic evaluation and impact assessment of ITS services - and apply it to before and after (ex-post and ex-ante) evaluation of the services deployed. (See Project Appraisal and Evaluation)

Strategic planning for different purposes

The role of the public sector in ITS service delivery needs to be reviewed regularly as part of the strategic planning process. In many countries the role of the public sector has changed during the past decade from being a service developer and provider to becoming an enabler and purchaser of ITS services. The public sector can create the business framework by clarifying the institutional set-up and market conditions, including the regulatory requirements for ITS service deployments. This is especially important in countries with emerging economies.

Investment in ITS by the public sector needs to aligned with public policy and the current objectives for transport and mobility. These may change as the political landscape changes. This will affect the ITS planning phase when policy objectives are prioritised and resources allocated.

Those involved in strategic planning for ITS must keep the political perspective in mind - for example, where privacy concerns could lead to public opposition to an ITS deployment such as the introduction of new tolls and charges, requiring additional measures to protect data security and the privacy of financial transactions. In general, ITS is often “invisible” to the politicians and media until something goes wrong in its deployment, operation or use of ITS.

When planning an ITS deployment for the first time, the classical approach – as with any new investment – is to determine the user's needs. For example, there may be a need to improve safety, or to manage congestion, or a combination of both – or some other traffic issues which needs managing for policy reasons.

The next step is to determine the extent of the ITS requirements that provide the control capability that meets the needs and manages the traffic appropriately:

From this assessment a business case can be developed through an analysis of costs and benefits. (See Understanding the Costs and Benefits of ITS) This is essential to ensure a healthy rate of return on the investment to justify the project – and ensure that the investment compares favourably with other transport investments. (See Project Appraisal )

Where a programme of ITS projects is envisaged, covering a number of highways and urban locations (such as a network of road intersections), developing a business case repeatedly, for each project, is time-consuming and expensive. In general, highways of the same type, that carry similar volumes of traffic – and have similar safety and congestion issues – will usually merit similar investments in ITS equipment and infrastructure to achieve a common level of service. In these circumstances it is possible to develop a “generic” business case, based on a common level of ITS provision – one that has been shown to satisfy the identified “need”, meet operational requirements and importantly, demonstrate a positive benefit/cost ratio (BCR).

Once that business case is proven, it is possible to establish a common requirement for ITS deployment on roads and highways of the same (or very similar) type. The traffic and other site-specific parameters that justify this level of provision can be quantified and applied as a check-list or formula (for example, by measuring traffic flow data and accident and congestion records).

Through sensitivity testing, the range for each parameter – where the business case remains positive – can be determined to establish minimum qualifying criteria. Any road meeting or exceeding the prescribed criteria would justify having the same level of ITS provision as the project for which the business case was first developed showing a positive BCR. That level of ITS provision can then become the accepted requirement for highways and locations of the same type.

Having a common level of provision on roads of similar types and with similar levels of traffic has other benefits besides the time and expenditure savings arising from not having had to undertake a cost-benefit analysis or develop a business case for each project:

Adopting a policy to specify uniform levels of ITS provision has the advantage of reducing project design and preparation costs and other savings. It is essential to avoid technology lock-in (becoming tied into the current generation of technology). This can be avoided by specifying functionality and performance and making use of non-propriety (open) interface standards.

Where ITS is being deployed for the first time there is unlikely to be a Traffic Management Centre (TMC). In these circumstances the first ITS project will be the commissioning of a TMC of such a size as neded to cover the expense of its operation:

In the UK, when incident detection and automatic signalling were being added to an existing inter-urban traffic management system, a cost benefit analysis was undertaken based on accident and delay saving benefits - to produce a generic business case. Sensitivity testing of the cost/benefit model gave a traffic flow figure for motorways above which, the probability of accidents meant that the accident and delay saving benefits exceeded the cost of installing incident detection. In this case, the criteria derived to justify adding incident detection to a section of motorway, came in the form of a traffic flow-rate per lane of motorway. This standard of provision prescribed that all motorways with more than 20,000 vehicles per lane per day justified the addition of incident detection. A study ten years after the first installation confirmed that the criteria being applied – and the generic business case – were correct.

The full benefits of ITS can be realised only if the many stand-alone traffic and travel information systems are integrated within a region. However, integration is not as straightforward as some might expect.

The first practical issue in regional deployment has to do with its scope. In order to define a “region” in which ITS applications are to be integrated, one has to consider integration at different levels – domestic integration within a country, international integration with trade partners or with geographical neighbours. For example, Mexico has problems of domestic integration among its seven regions because standards for ITS-related subsystems and levels of available information are very diverse among these regions. Internationally, Mexico has faced problems integrating with its trade partners within NAFTA on the one hand because Canada and US have more developed ITS technologies, and integrating with other Latin American states on the other hand because their ITS are less developed.

The size of the region will determine the level of interoperability that is required. The appropriate scale of deployment depends on specific applications. International cargo identification and freight transport can benefit greatly from interoperability among nations for the sake of efficiency and security. Standard toll collection devices for a region are more important for trucks moving freight across a sub-continent than for passenger vehicles that stay in the same metropolitan area most of the time. This has led to the suggestion of ETC - based on GPS for trucks, and DSRC for cars. Cross-border traffic information has become important in Europe as many vehicles frequently travel between countries. Other ITS applications work best on a smaller scale - such as local traffic management and control.

People and organisations have different objectives, motivations and attitudes - and their diversity is greater the wider the region to be integrated. Although most institutional problems could be alleviated by legal and contractual arrangements, building consensus requires seed funding. Conditional funding for regional deployment - as often provided in Canada - has been found to be beneficial where no money is available from government unless and until consensus is reached.

If used appropriately, system architecture can help high-level decision makers to understand the functioning of ITS and to cooperate in its deployment. (See ITS Architecture) Ideally, where an architecture is used - a regional architecture should be developed to support regional deployment in a way which is consistent with the national architecture. In the absence of a national architecture, the development of a regional architecture at a lower level may be sufficient. Using this bottom-up approach, a regional architecture can evolve from either a “concept of operations” or from technical specifications based on regional objectives.

Voluntary harmonisation and interoperability can also be achieved by specific regional ITS projects oriented towards this goal - and involving "all" regional partners. Good examples include the European EasyWay action, which has, with European Commission support, produced ITS Deployment Guidelines for many ITS services - and the Asia-Pacific ITS Guidelines aiming to harmonise the national ITS Master Plans for sustainability. (See Deployment Guidelines and Asia-Pacific ITS Guideline)

Research and Development goes hand in hand with deployment and is a major tool in strategic planning.

Firstly, research, development and innovation activities provide technology development and new solutions for ITS infrastructures and services. These new solutions need to be considered in strategic planning in terms of whether, when and by whom they should be utilised.

Secondly, research evaluating the impacts of ITS on behaviour, traffic, the economy, transport policy objectives and society as a whole, provides knowledge on the effectiveness of the new solutions, and paves the way for full-scale deployment and standardisation efforts. An ITS Strategy together with its action plan can be assessed during its development process - particularly when prioritising objectives and the actual actions.

Thirdly, research can provide the foundations of ITS Strategies or Framework Plans - by studying user needs, likely technology developments (technology foresights) and possible future scenarios.

Finally, an ITS research strategy should ideally accompany an ITS Deployment Strategy. This has been the case, for instance, in the USA where a specific ITS Strategic Research Plan was produced at the same time as the ITS strategy (See ITS Strategic Research Plan). The research plan should reflect the priorities of the medium-term and long-term ITS strategies.