Strategic planning is designed to help organisations (and communities) respond effectively to new situations. It is a disciplined approach to inform decision-making and plan the nature and direction of an organisation’s activities. These decisions typically concern the organisation’s mandate and mission, its end-product and service level - taking into account cost, financing, management and organisational set-up.

Across the world, the deployment of intelligent transport systems has been slower than anticipated, not because of technological limitations, but because of non-technical concerns such as institutional issues and commercial considerations. Although the vision for the role of ITS may be clear, in practice the path to deployment is often problematic. For example, ITS may require organisations to develop an operational capability that was not required previously. (See Basic ITS Concepts and Integrated Operations) ITS may also require heavy investment in “hard” and “soft” ITS infrastructure and “infostructure” involving the use of fast developing technologies. (See ITS Technologies).This can raise major public policy considerations, not least the appropriate level of public finance, or the contractual terms and conditions for private sector promoters of ITS. (See Procurement and Competition and Procurement)

At the local level, policy relates to activities within the political control of regional, metropolitan, rural and other non-national government bodies - such as network management of local roads and public transport, parking, environment, travel information. Public authorities need to create a framework within which to analyse and assess ITS services, both from the point of view of individual ITS applications and - at a more general level - from the perspective of the urban planning and the transport authorities in a city or region.

The context for deployment of ITS is the basic organisational, regulatory and institutional framework within which system development and service set-up take place. It will shape the environment within which the different ITS services are developed, deployed, operated and maintained. A well planned set-up which is accepted by all key stakeholders will improve the commercial and public sector business cases - with appropriate risk distribution, cost-sharing, service pricing and optimal quality delivery. (See Legal and Regulatory Issues)

In practice the context for deployment is constantly changing due to technological breakthroughs, and political, economic, environmental and demographic trends - which affect both the supply and the demand for ITS and other services. ITS deployment needs to be considered from a number of perspectives.

The market for ITS services, infrastructure and info-structure have been growing fast in areas such as navigation, tolling, driver support, telecommunications and digital mapping. The private sector, operating in the market, is constantly looking for a sound business case - in other words: sufficient revenue, return on investment and recovery of development and operating costs. Companies aim to build up demand for their services and products, increase the size of the market and their own share of the market - so their interests include:

The private sector will benefit from early knowledge of the public sector stakeholders' strategies and plans so they can respond appropriately to safeguard and advance their own interests. Companies follow closely, the development of markets, undertaking market research and analysis. They are usually able to make decisions and implement actions very quickly - often within a few months. This enables them to react to public sector strategic initiatives quickly - although planning processes do vary greatly amongst companies.

Road authorities and other public sector stakeholders plan their activities based on policy objectives and priorities. Some are directly transport-related such as road safety, congestion, traffic noise and emissions. Others arise from policy areas and objectives such as industrial competitiveness, climate change, energy sustainability and the information society.

Public sector planning usually involves three different time scales:

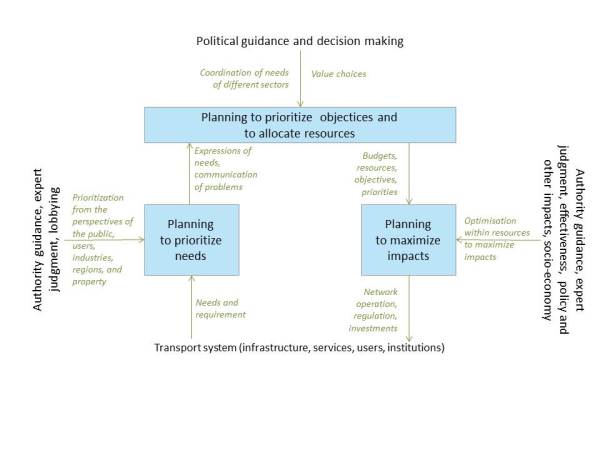

The planning processes, outlined in the figure below, includes the following stages:

To facilitate planning, public authorities need to create a framework for the socio-economic evaluation and impact assessment of ITS services - and apply it to before and after (ex-post and ex-ante) evaluation of the services deployed. (See Project Appraisal and Evaluation)

Strategic planning for different purposes

The role of the public sector in ITS service delivery needs to be reviewed regularly as part of the strategic planning process. In many countries the role of the public sector has changed during the past decade from being a service developer and provider to becoming an enabler and purchaser of ITS services. The public sector can create the business framework by clarifying the institutional set-up and market conditions, including the regulatory requirements for ITS service deployments. This is especially important in countries with emerging economies.

Investment in ITS by the public sector needs to aligned with public policy and the current objectives for transport and mobility. These may change as the political landscape changes. This will affect the ITS planning phase when policy objectives are prioritised and resources allocated.

Those involved in strategic planning for ITS must keep the political perspective in mind - for example, where privacy concerns could lead to public opposition to an ITS deployment such as the introduction of new tolls and charges, requiring additional measures to protect data security and the privacy of financial transactions. In general, ITS is often “invisible” to the politicians and media until something goes wrong in its deployment, operation or use of ITS.

When planning an ITS deployment for the first time, the classical approach – as with any new investment – is to determine the user's needs. For example, there may be a need to improve safety, or to manage congestion, or a combination of both – or some other traffic issues which needs managing for policy reasons.

The next step is to determine the extent of the ITS requirements that provide the control capability that meets the needs and manages the traffic appropriately:

From this assessment a business case can be developed through an analysis of costs and benefits. (See Understanding the Costs and Benefits of ITS) This is essential to ensure a healthy rate of return on the investment to justify the project – and ensure that the investment compares favourably with other transport investments. (See Project Appraisal )

Where a programme of ITS projects is envisaged, covering a number of highways and urban locations (such as a network of road intersections), developing a business case repeatedly, for each project, is time-consuming and expensive. In general, highways of the same type, that carry similar volumes of traffic – and have similar safety and congestion issues – will usually merit similar investments in ITS equipment and infrastructure to achieve a common level of service. In these circumstances it is possible to develop a “generic” business case, based on a common level of ITS provision – one that has been shown to satisfy the identified “need”, meet operational requirements and importantly, demonstrate a positive benefit/cost ratio (BCR).

Once that business case is proven, it is possible to establish a common requirement for ITS deployment on roads and highways of the same (or very similar) type. The traffic and other site-specific parameters that justify this level of provision can be quantified and applied as a check-list or formula (for example, by measuring traffic flow data and accident and congestion records).

Through sensitivity testing, the range for each parameter – where the business case remains positive – can be determined to establish minimum qualifying criteria. Any road meeting or exceeding the prescribed criteria would justify having the same level of ITS provision as the project for which the business case was first developed showing a positive BCR. That level of ITS provision can then become the accepted requirement for highways and locations of the same type.

Having a common level of provision on roads of similar types and with similar levels of traffic has other benefits besides the time and expenditure savings arising from not having had to undertake a cost-benefit analysis or develop a business case for each project:

Adopting a policy to specify uniform levels of ITS provision has the advantage of reducing project design and preparation costs and other savings. It is essential to avoid technology lock-in (becoming tied into the current generation of technology). This can be avoided by specifying functionality and performance and making use of non-propriety (open) interface standards.

Where ITS is being deployed for the first time there is unlikely to be a Traffic Management Centre (TMC). In these circumstances the first ITS project will be the commissioning of a TMC of such a size as neded to cover the expense of its operation:

In the UK, when incident detection and automatic signalling were being added to an existing inter-urban traffic management system, a cost benefit analysis was undertaken based on accident and delay saving benefits - to produce a generic business case. Sensitivity testing of the cost/benefit model gave a traffic flow figure for motorways above which, the probability of accidents meant that the accident and delay saving benefits exceeded the cost of installing incident detection. In this case, the criteria derived to justify adding incident detection to a section of motorway, came in the form of a traffic flow-rate per lane of motorway. This standard of provision prescribed that all motorways with more than 20,000 vehicles per lane per day justified the addition of incident detection. A study ten years after the first installation confirmed that the criteria being applied – and the generic business case – were correct.

The full benefits of ITS can be realised only if the many stand-alone traffic and travel information systems are integrated within a region. However, integration is not as straightforward as some might expect.

The first practical issue in regional deployment has to do with its scope. In order to define a “region” in which ITS applications are to be integrated, one has to consider integration at different levels – domestic integration within a country, international integration with trade partners or with geographical neighbours. For example, Mexico has problems of domestic integration among its seven regions because standards for ITS-related subsystems and levels of available information are very diverse among these regions. Internationally, Mexico has faced problems integrating with its trade partners within NAFTA on the one hand because Canada and US have more developed ITS technologies, and integrating with other Latin American states on the other hand because their ITS are less developed.

The size of the region will determine the level of interoperability that is required. The appropriate scale of deployment depends on specific applications. International cargo identification and freight transport can benefit greatly from interoperability among nations for the sake of efficiency and security. Standard toll collection devices for a region are more important for trucks moving freight across a sub-continent than for passenger vehicles that stay in the same metropolitan area most of the time. This has led to the suggestion of ETC - based on GPS for trucks, and DSRC for cars. Cross-border traffic information has become important in Europe as many vehicles frequently travel between countries. Other ITS applications work best on a smaller scale - such as local traffic management and control.

People and organisations have different objectives, motivations and attitudes - and their diversity is greater the wider the region to be integrated. Although most institutional problems could be alleviated by legal and contractual arrangements, building consensus requires seed funding. Conditional funding for regional deployment - as often provided in Canada - has been found to be beneficial where no money is available from government unless and until consensus is reached.

If used appropriately, system architecture can help high-level decision makers to understand the functioning of ITS and to cooperate in its deployment. (See ITS Architecture) Ideally, where an architecture is used - a regional architecture should be developed to support regional deployment in a way which is consistent with the national architecture. In the absence of a national architecture, the development of a regional architecture at a lower level may be sufficient. Using this bottom-up approach, a regional architecture can evolve from either a “concept of operations” or from technical specifications based on regional objectives.

Voluntary harmonisation and interoperability can also be achieved by specific regional ITS projects oriented towards this goal - and involving "all" regional partners. Good examples include the European EasyWay action, which has, with European Commission support, produced ITS Deployment Guidelines for many ITS services - and the Asia-Pacific ITS Guidelines aiming to harmonise the national ITS Master Plans for sustainability. (See Deployment Guidelines and Asia-Pacific ITS Guideline)

Research and Development goes hand in hand with deployment and is a major tool in strategic planning.

Firstly, research, development and innovation activities provide technology development and new solutions for ITS infrastructures and services. These new solutions need to be considered in strategic planning in terms of whether, when and by whom they should be utilised.

Secondly, research evaluating the impacts of ITS on behaviour, traffic, the economy, transport policy objectives and society as a whole, provides knowledge on the effectiveness of the new solutions, and paves the way for full-scale deployment and standardisation efforts. An ITS Strategy together with its action plan can be assessed during its development process - particularly when prioritising objectives and the actual actions.

Thirdly, research can provide the foundations of ITS Strategies or Framework Plans - by studying user needs, likely technology developments (technology foresights) and possible future scenarios.

Finally, an ITS research strategy should ideally accompany an ITS Deployment Strategy. This has been the case, for instance, in the USA where a specific ITS Strategic Research Plan was produced at the same time as the ITS strategy (See ITS Strategic Research Plan). The research plan should reflect the priorities of the medium-term and long-term ITS strategies.

The development of an ITS Strategy or Framework Plan needs to bring together the main stakeholders and agencies involved in deploying future ITS systems and services. To win their support, it is helpful to have clear vision of how ITS should develop. ITS needs technical and political champions who will generate support for the vision. Whoever champions the realisation of that vision will need advice to fulfil their informed customer role in the face of rapidly changing technological capabilities.

Mature, integrated ITS services and service markets are something that evolves over a period of time. Countries, regions, and cities can lay the foundations by developing a strategic framework and a common plan to provide direction to ITS deployments locally - or by organisation. A national, regional or local ITS policy framework provides an opportunity to analyse the requirements for deploying ITS, and to assign roles and responsibilities, budgets and priorities. It should reflect the market, policy and political perspectives as the context for the deployment.

A policy and coordination framework is aimed at coordinating the actions of the lead actors on the basis of a mutually-agreed vision of the future. To guarantee buy-in by all the stakeholder groups, the planning process must involve the representatives of those groups. Examples of ITS deployment strategies developed in a multi-stakeholder cooperation include the US ITS Strategic Plan (See the U.S. ITS Strategic Plan) from 2009 and its planning workshops (See ITS planning workshops), the EU ITS Action Plan from 2009 (See EU ITS Action Plan) and the Finnish ITS Strategy from 2013. (See Finnish ITS Strategy)

A well-developed ITS Framework will provide the basis for specifying ITS system architecture and for considering the ways in which individual ITS systems can be integrated. The deployment path is likely to be a set of upgrades or improvements to existing systems and services - as well as deployment of completely new systems and services. Prudent ITS implementation will be based on an evolutionary strategy that begins with small steps whilst keeping the future big picture in mind and maintaining at all times the provision of services under improvement. By choosing "early winners" - initial deployments that are relatively small and have a high probability of early success - it will be possible to show the efficiency and effectiveness of ITS investments early on to ensure the continuing interest and support of key stakeholders.

The ITS strategy should also consider the role of private, commercial ITS services as well as public ITS services. The benefits of inter-agency and inter-jurisdictional discussions, negotiations, and agreements should also be analysed.

In developing the ITS strategy and policy framework, it is advisable to establish today's situation - as a quantified baseline for future evaluation. To be meaningful, the progress of the plan needs to be assessed periodicly - around every 3-5 years. Priorities should be based on the results of evaluations of ITS deployments as well as the results of research, development, pilot projects and field operational tests (See Project Appraisal and Monitoring and Evaluation). A good example of a local ITS strategy is provided by Seattle in the USA. (See Seattle ITS Strategic Plan 2010-2020 and Strategic ITS Plan)

The process of developing an ITS Strategy or Framework Plan with multi-stakeholder cooperation contains a number of steps, which are described below.

The starting point is to determine the major transport issues which ITS should address. Ideally, this will be based on a survey of the needs of users: shippers, carriers, distribution companies, bus and coach operators, commercial bodies, private individuals, and national and regional governmental organisations. The Framework needs to respond to current policy issues such as environmental sustainability, economic development, safety and security. A good example of such an analyses is the European Commission's Urban Mobility package from 2013.

The aim of a needs-driven Framework plan should be to define the basic supporting infrastructure for ITS - using existing services, projects and infrastructure as a springboard where possible. Existing services and projects that use ITS technology should be identified and brought within the scope of the plan. The Framework needs to be developed through discussion, consultation and meetings with the major stakeholders - and augmented, if appropriate, by dialogue with key decision makers and politicians. The work can include mapping of transport problems to ITS user services. (See Benefits of ITS) ITS functions - or user services - relevant to industrial and regional needs should also be identified and prioritised.

An important input to the ITS Framework Plan is developing an inventory of existing ITS systems and services - that are either already operating or under development. This step follows on naturally from the analysis of stakeholders. For example, some of the road authorities and operators may already be operating freeway management, incident detection and management, or traffic signal control. They might add to these public transport management, emergency management, and advanced information systems in the pipeline. The future of these (what will become “legacy systems”) must be addressed specifically in the ITS Framework Plan. Decisions will be needed on whether to retain and upgrade them or to invest in new systems that have improved capabilities and performance. Decisions to terminate some services or to scrap some systems may also be taken in favour of purchasing better services from the ITS service market or using more cost-efficient technology solutions.

It is likely that a number of different organisations will need to ‘buy in’ to the overall vision for ITS and the implementation process to make the vision a reality. Harmonising the positions of the principal stakeholders is probably the most important aspect for the deployment and operation of ITS. The successful development of new services will be much easier if stakeholder's individual motivations and interests can be aligned. Close contact with the key actors is needed throughout the planning and deployment process.

The list of organisations which might be involved can be extensive but only a few will play a leading role. The ITS service providers will naturally need to be involved. Almost certainly the list will need to include the agencies involved in operating the major highways, the local authorities responsible for the main arterial roads and local roads, the traffic police and other traffic management agencies. Depending on the specific ITS application, the operators of commercial vehicles, public transport operators, and the motoring organisations representing private motorists, may also need to be involved.

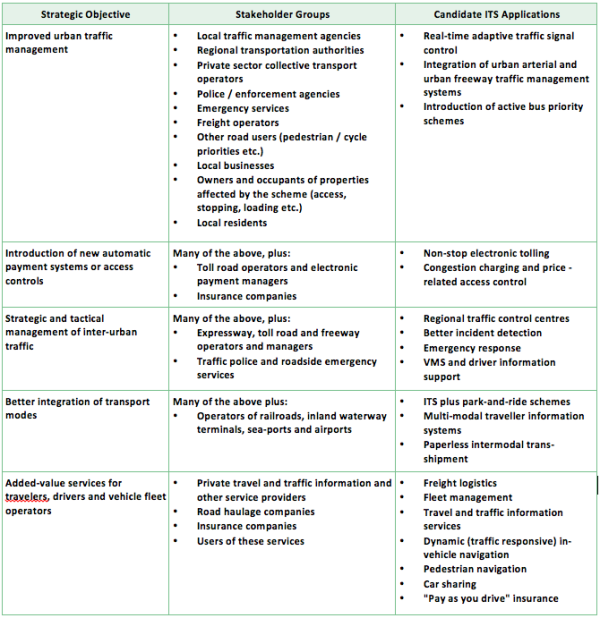

Experience shows that ITS services involve an increasing number of organisations as the full potential of the new technologies is realised. The table below illustrates this point with examples of the more common objectives for investing in ITS - showing the varying degrees of complexity and stakeholder groups. Senior officials of public agencies and chief executives of private sector companies will often be involved in the definition of the ITS Framework Plan - because of the level of commitment that is required to make the plans become a reality.

The body of stakeholders which will need to be consulted during the decision-making process depends on the local situation and the issues at hand. It is important to be aware and sensitive to potential issues at all times - in what may be an evolving situation - as ITS services develop. Even apparent minor stakeholders can introduce issues which must be recognised and dealt with. Generally it is better to uncover and address any issues early on in the planning stages, so proper adjustments can be made. An effective communication strategy with the stakeholders provides the opportunity to develop contingency options.

Figure 2. Examples of Stakeholders for ITS Projects

If the consultations and preparation work has been done effectively the ITS Framework Plan will be supported by all the leading actors. For deployment to proceed, their awareness of ITS, and expectations of it, must be compatible. Focusing on ITS services as a whole, will enable identification of those services and enabling systems with a broad context - which will require support from a strategic ITS framework. The architecture may need to support localised services such as common infrastructure used by ITS - for example communications networks, data exchange protocols, electronic payment services, where economies of scale and standards are required for economic viability.

The issue of multiple organisations, data and information exchange needs to be addressed both psychologically and institutionally. In day-to-day operations, protection of jurisdictional authorities and responsibilities is one of the most common problems encountered when integrating regional traffic control. Organisational culture conflicts need to be resolved in ITS public-private partnerships. Each of the multiple organisations involved has its own history and standard operating procedures that can make it difficult to build the necessary partnerships. While group decision theory (based on the concept of win-win solutions) may apply reasonably well to these situations, game theory (based on minimum-maximum principles which evaluate strategies under worst-case scenarios) may be more relevant to handle newer ITS applications - such as combatting or alleviating the impact of terrorist or cyber attacks.

The promoters of ITS services or projects need to consider the following:

Experience shows that it is helpful for the key actors to agree:

The ITS Strategy or Framework Plan should be published alongside a set of documents which will describe the proposals and provide a basis for agreement between all the stakeholders. These documents will together provide the basis for further refinement and consensus building during the subsequent stages of ITS deployment. Together they will provide a comprehensive statement of the ITS policies and priorities and what is to be achieved.

Examples of the type of documents which should be published are:

ITS services are the result of specific value chains varying according to the specific service - but with the same basic functionalities. The figure below presents a generic value chain for travel and traffic information services - but it applies to most ITS services. Each of the functions in the value chain specifies a responsibility for carrying out a specific task - and that responsibility is assigned to one or more of the organisations involved.

Traffic information service value chain by TISA Lohoff, Jan 2013.TISA WG Quality: Quality criteria and methods. Presentation at the European ITS Platform WP 3.2 and 3.3 Kick-Off Meeting. Brussels, 27 November 2013.

The roles of road authorities and other public sector stakeholders differs depending on the ITS service in question. Typically, road authorities have a more prominent role in services related to their core business of network operations, such as freeway management, traffic management, and incident management. They do not, though, have any major role in most vehicle based systems - such as driver support systems. In addition to the roles in the value chain, the public sector is always responsible as the regulator for any regulations or legislation setting out the legal framework for ITS service provision.

The roles of different stakeholders - and the borderline between public and private stakeholders - varies depending on national organitaional cultures and traditions. In some countries, the public sector stakeholders have responsibility for most parts of the value chain - such as real-time traffic event information services - whereas in other countries, the public sector is only involved in providing data for these services.

There is no single correct model of division of responsibilities for ITS services. Each ITS service has its own value chain or network, and the roles and responsibilities are determined by the local organisational cultures, tradition, conditions, markets and economic situation. Sometimes, the public sector needs to take a more active role than expected - such as when the private sector will not, by itslef, provide a socio-economically beneficial ITS service in areas of the public sector's jurisdiction.

ITS covers a wide range of systems and services. Different stakeholders are involved - and their roles and attitudes, as well as legal and institutional issues - vary in each ITS deployment. Whilst there will be wide variations between different applications and individual institutions - three broad groups of stakeholders investing in ITS can be distinguished:

1) Users and consumers of ITS (corporate or individual): require systems and services that meet their real needs. They have high expectations of service quality, reliability and availability (dissemination channels). The willingness to pay for ITS systems and services strongly depends on the actual and perceived utility of the service as well as on its image. The acceptable price may not correspond to the actual costs of service generation and delivery

2) The public sector: will adopt ITS to deliver various public services, objectives and strategies. Where these are made explicit - public interests in ITS service development are usually justified by positive impacts on traffic management and modal shift, road safety, sustainability, economic development, business location, image and social inclusion. Public authorities then seek to involve the private sector so as to mobilise the enterprise culture, limit public expenditures and increase efficiency

3) The private sector: share the objectives of marketing their products/services through ITS, entering a future growth market - and/or developing a new profitable business area. In this, the private sector depends heavily on the framework conditions established by the public sector - which they soemtimes perceive as an obstacle to the free market. On the other hand, differences between various private sector stakeholders leads to different orientations and priorities when defining new ITS service delivery models. These differences need to be recognised in the strategic agreements with the public sector.

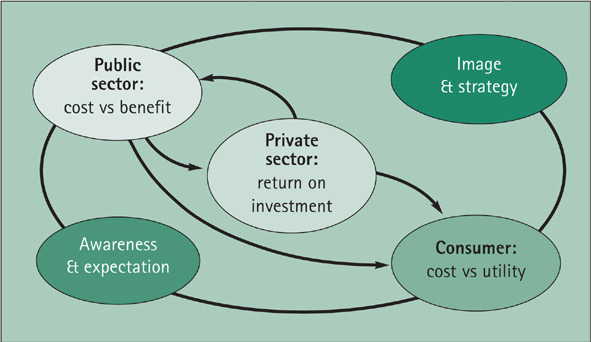

Three very different business model evaluation systems come into play - as these groups consider whether to allocate their budgets to ITS.

1) The consumer (any individual or organisation that is the end user of an ITS system or service) evaluates the utility of ITS in relation to the buy-in cost and any recurring fees and charges that have to be aid.

2) The public sector usually has to justify investment in ITS on the basis of public service criteria or the benefits to the community - including affordability of the initial capital spend and any maintenance and long-term operating costs. There are several alternative evaluation methods (See Project Appraisal and Monitoring and Evaluation).

3) The private sector is concerned with the forecast return on the investment needed to bring ITS equipment, products and services to market - and the extent and reliability of any revenue streams

The interactions between these very different requirements are shown schematically below. ITS projects will frequently require justification against at least two, if not all three of the underlying business models. Failure to meet one or other of the investment tests will produce a classic “chicken and egg situation” – who goes first, the supplier or the purchaser in making a commitment to the system or product? Experience shows that this dilemma has been resolved in countries like USA and Japan by the public and private sectors jointly developing a strategic plan - including an ITS architecture that clearly defines the institutional responsibilities. When starting up cooperative system deployment in Europe - the Amsterdam group (See Amsterdam Group) consisting of vehicle manufacturers, road authorities, cities and private road operators - agreed on a road map with specific milestones reinforced by a common Letter of Intent signed by all, and a dedicated Memoranda of Understanding between the relevant local, regional and national stakeholders involved in different local deployments.

Interdependencies between the public sector and consumers.

The road authorities and other stakeholders involved in ITS services need to interface with stakeholders across the value chain. The success of the ITS service value chain hinges on successful cooperation between the different stakeholders and their functions in the chain. This is not restricted to public sector agencies only, but will also include private stakeholders. Today, it is also part of the role of Network Operators to enable and facilitate value-added service development.

The ITS Framework Plan and any ITS Architecture - are high-level reference documents which set the context for deployment. As ITS projects develop and services come on stream it is necessary to be claer about legal and institutional issues, operational requirements and other stakeholder issues. For example, where the roles of different actors in the information supply chain is unclear - they need to be defined.

The timing of a project will often be dictated by budgetary considerations, even for high-priority projects with large benefits. Sometimes projects will be delayed due to a shortage of personnel with the necessary skills. Political factors will also impact on the timetabling - and can include the public visibility of the project and the potential impact of the investment on users.

Public objection or misunderstanding can lead to ITS projects being abandoned. For example, road pricing or congestion charging has, until recently, run into difficulties in securing public acceptance for various political reasons. The early introduction of road pricing in Hong Kong in the 1980s raised public suspicion about the use of AVI for “big brother surveillance.” This can have an impact on the implementation timetable - it may, for instance, be advisable to give priority to those investments which will deliver the highest benefits at the lowest risks or those investments which will deliver benefits to a greater number of stakeholders.

It is a real challenge to acheive an appropriate level of co-ordination and to create synergy benefits between the different stakeholders without bureaucratic costs. Administrative procedures can be a real obstacle - for example, different administrative procedures in adjacent administrative areas may need to be harmonised. New safety arrangements, operational procedures or detailed local operating agreements may also need to be developed and implemented to deal effectively with new measures - such as the installation and maintenance of roadside detection equipment. This can also take valuable time

ITS operational requirements are frequently geared to an operations or control centre at the hub of the ITS service, for example:

For many specific ITS projects, there will be a lead agency - which will be the organisation most closely associated with promoting the proposed ITS investment or the delivery of the new ITS service. New business units will oftent need to be created to cut across the traditional lines of responsibility between agencies - this is because ITS technology both requires and offers, new and greater opportunities for integrated deployment and interagency working.

For data exchange there is a need to create supply chain contracts, codes of practice - and to respond to other requirements. The availability of public data and distribution channels needs to be regulated in a legal framework - which should define objectives and public and private sector responsibilities. Data publishing, and distribution policy and practice will also need to be resolved (free at point of use, added value services; intermodal/ inter-agency exchange). There may be other legal issues to be addressed as well - such as data confidentiality.

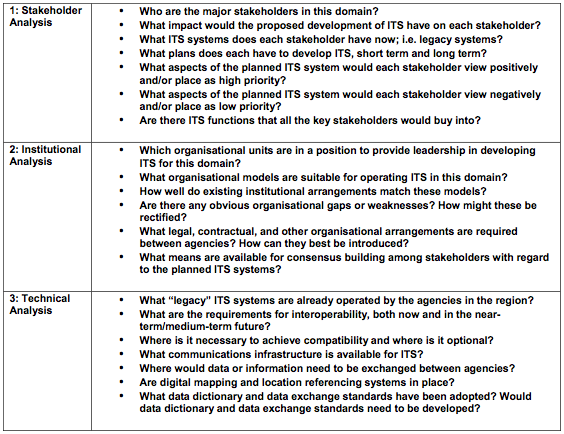

Resolving the institutional issues needs to proceed in parallel with the technical aspects of ITS project planning. The specific ITS development must be assessed for its feasibility and desirability in the local context - from both a technical and non-technical perspective. There is usually more than one way to implement an ITS project - for example:

The type of implementation chosen will be governed by many factors. Some key inputs are listed in the figure below.

Figure 5. Checklist for use in developing a road map for ITS deployment

The ITS Road Map is a means of translating concepts and plans into reality. It assigns roles and responsibilities and specifies how stakeholders can organise themselves to implement the recommendations of the Framework Plan. The following is a checklist of topics which will need to be addressed:

Human Resources

Contractual and Legal Requirements

Effective dialogue between the main stakeholders is the key to transforming organisational arrangements from concept into reality. A task force of the major players can help to develop voluntary agreements and Memoranda Of Understanding (MOUs) on matters of common concern. For example, in Europe, MOUs on cross-border data exchange and on the provision of the language-independent Radio Data System / Traffic Message Channel (RDS/TMC) on FM radio were agreed in fora which provided the opportunity for all interested parties to work together to discuss problems and agree on practical solutions.

The body which is made responsible for the high-level coordination of ITS developmen must have sufficient standing to be able to influence the decisions of key stakeholders on issues such as conformance to ITS architecture, data exchange formats and the use of standards. A good example is the European ITS Directive (See ITS Directive) which determines the specifications which specific ITS services must follow for deployment in Europe. The roll-out of ITS services may also require voluntary cooperation agreements.

A national or regional steering committee with high-level political backing can be very effective in bringing together all the main stakeholders to focus on achieving a common goal. It requires the support of a dedicated interagency coordination unit or some kind of technical panel drawn from the participating authorities. International, national, and regional public/private partnership organisations - such as ITS America, ITS Canada, ITS Europe (ERTICO), ITS United Kingdom, ITS Australia, and ITS Japan (VERTIS) - can play a useful part in setting up this consultation machinery.

In parallel, at the national or regional level, it may also be useful to create an advisory panel of other major stakeholders in ITS - including any significant private-sector actors - for advisory purposes. The Minnesota Guidestar Program14 in the USA follows this practice. In Paris, there is the Consultative Committee on Road Information Broadcasting for service providers. In Japan, the VICS Coordinating Council, has responsibility for planning the VICS advanced traveller information system. In Europe, the ITS Advisory Group (See ITS Advisory Group), performs this role in relation to the ITS Action Plan and Directive.

Inter-agency and inter-company cooperation requirements may need to be formalised. Public/public, public/private, and private/private collaboration agreements and contracts are often needed. These agreements can range from informal agreements to cooperate on day-to-day operational tasks - to more ambitious and formal contracts and Memoranda of Understanding (MOU) which involve sharing of common systems. Midway between these two are the agreements on data exchange - specifying the agreed data formats and minimum data quality requirements (such as accuracy, timeliness, and extent of data consolidation or editing).

The contractual relationships and information flows involved in delivering ITS-based information services can be quite complex. For example, a private sector service provider may need to secure contracts at five levels:

Much of the groundwork will have been completed at the ITS Framework Plan stage. If the ITS architecture analysis has been planned effectively, the requirements for exchange and transmission of data, information, and other electronic transactions between agencies can be specified in fairly precise terms. This practice is recommended to ensure that the operational requirements of all the parties will be satisfied. The main steps are as follows:

It is likely that no two stakeholders will have precisely the same set of requirements - since each has individual needs and resources. If it is appropriate - the detailed requirements and responsibilities can be formalised in contracts or formal agreements - so that the receiving party can rely on a minimum performance specification from the provider, and there is a means of redress if this minimum is not achieved.

A good communication and public information strategy is very important - and needs to be kept up to date during project management. Neglecting the communication strategy and not implementing it in a timely way, can lead to the failure of projects - whilst paying proper attention to the communication strategy and its implementation can foster their success. In the 1990s a pioneer project in electronic payment, the Trondheim Toll ring, gained public support, partly because of the positive publicity it received. Similarly the original California Smart Corridor is another example of a successful project supported by an effective communication strategy. The outcomes might have been different - because of the number and the level of bodies involved - but all parties cooperated around a common mission.

Where possible, a Programme Manager should be appointed to bring communication, attention to detail, and energy - to overcome institutional problems. The Programme Manager can provide drive and co-ordination from project start through to deployment.

The involvement of private stakeholders has been increasing in both network operations and ITS service provision. This highlights the need for the public sector to work in partnership with commercial and private stakeholders - and to interface with them in a way that is even-handed in all parts of the life-cycle of a service, from idea, through development, to large-scale deployment. There are several mechanisms and solutions that provide appropriate contractual and operational partnerships. (See Finance and Contracts)

Traditionally, road network operators have provided all infrastructure systems as part of their network responsibilities. These have included systems such as traffic signals, dynamic message signs, and toll collection. Telecommunications and broadcast radio providers have similarly been responsible for the systems and networks that their services use. The automobile industry has produced systems for in-vehicle use - including a range of radio and mobile communication equipment.

Private sector involvement, often in some form of public/private partnership, poses new issues in relation to financing and procurement that are often unprecedented, complex - and not yet completely resolved. Private financing has been proposed for ITS projects because of the potential to combine public benefits with commercial opportunities.

Europe, Japan, and North America provide an increasing number of examples of private sector involvement in ITS. Private sector participation presents both new opportunities and challenges for transport professionals in both the public and private sectors. Public agencies are looking to the private sector - both for the investment in ITS infrastructure and for ITS operations and delivery of ITS Services. The reasons for this are many, but in general there are four principal motivations:

As we have seen, the ITS world is distinguished by the high investment that is often needed to achieve acceptable results. Investment cycles differ for public investment and commercial business - and the opportunity cost of private sector capital is much higher than for the public sector. Financial incentives that are underwritten by the public authorities may be appropriate where the socio-economic benefits are likely to be very high. As with other major infrastructure investments, the return on investment may be long-term, whereas private sector finance normally requires a short or medium payback period. This phenomenon may be an inhibiting factor in projects where the private and public sectors must cooperate.

Opportunities for private sector participation may be hampered by other factors, such as:

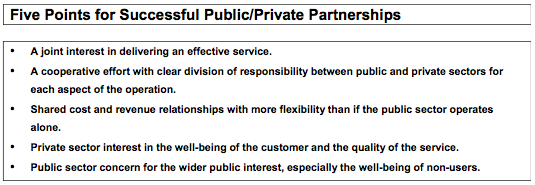

Notwithstanding these difficulties, public/private partnerships have the potential for creative synergy between the public sector organisational culture and the entrepreneurial approach. Both parties in the partnership can bring their own skills and expertise to the combined operations (see figure below). Specific private sector strengths are:

The private sector can also bring a strong profit motive and access to market funding - without the need to take into account the restrictions posed by public sector interagency demarcations. This is particularly important when trying to start up a new ITS operation that spans the responsibilities of different public agencies.

Conditions for a successful public/private partnership

The public sector strengths are very different:

There are major cultural differences to be bridged - notably the requirement for commercial secrecy regarding costs, revenue and profit, which runs counter to the public agency’s need for transparency and open accounting as a deterrent to the misuse or misappropriation of public funds. These differences need to be acknowledged and taken into account in partnership plans.

Building partnerships requires trust, understanding, commitment, and communication. When any of these ingredients is missing problems will arise, and when all of them are compromised, severe difficulties are inevitable. Without trust, achieving consensus on project direction and resolving technical issues becomes very difficult. Trust is built by working together toward common objectives and ensuring that the team members live up to their commitments. Understanding of the roles and responsibilities, and commitment to mutual goals, keeps the project moving towards deployment.

Setting a framework of rules and guidance, and removing institutional barriers to new and high priority ITS are some of the critical roles for which public authorities must assume responsibility. These institutional arrangements flow from the Framework Plan. Typically, in the area of commercial traffic and traveller information services, the private sector asks the public agencies to authorise some or all of the following:

The handling of many of these requirements will be specified in regional or national legislation and regulations - as well as different guidelines and recommendations, such as the European Directives on the open public data and the European Statement of Principles for HMI. (See Human Factors)

The UK requires operators of certain kinds of dynamic route guidance systems to be licensed by the government (real-time driver information, route guidance and navigation services) with powers to impose conditions on their operation. The conditions permit the installation of roadside equipment on the highway and can control which routes can be used (in the interests of orderly traffic management and road safety) and to assess the extent to which any in-vehicle displays have the potential to distract the driver. As the objective is to encourage competition in the provision of services, the presumption is against the granting of exclusive licences.