As with any other branch of information technology, ITS has seen an explosion in the capacity to generate, process and store data over the last decade or two, which will continue using what is nowadays “normal” computing capacity. Large volumes of data can be easily captured, collected, and stored in real-time and processed in a variety of ways. ITS applications draw on a wide range of data sources including details of vehicles, personal details of drivers and public transport users, bank details for electronic payment (tolls, tickets or a congestion charge), origin and destination of journeys, vehicle and personal location.

Data processing and data privacy legislation is constantly evolving to keep a balance between what the national authority and the general public consider desirable and reasonable in handling an individual’s or organisation’s data (the subject’s data). The principles of contract law and privacy legislation apply equally to ITS as they do to any other area of life. Ignoring these principles creates a risk that the ITS application will become a point of friction between authorities and the public. The challenge is to bear this in mind, even where the information appears at first sight to be non-sensitive.

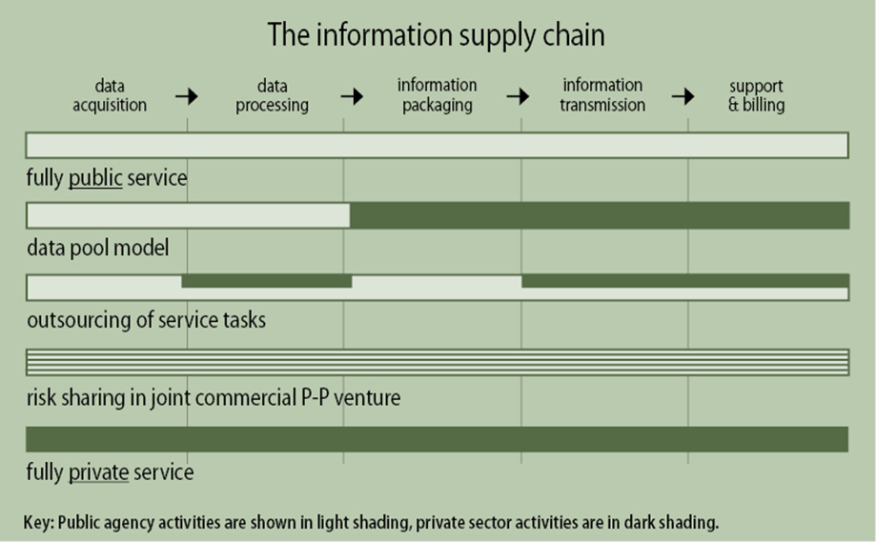

ITS applications cannot function without systematic capture and processing of data. The legal and organisational arrangements involved may be quite complex for even simple applications – such as real-time arrivals at a bus stop. In the case of ITS-based information services the flow of data and content can be organised between the public and private sectors in different ways – as shown in the figure below. The development and delivery of the information service to the end user depends on partnerships and contracts – from data acquisition through to service support and billing. Each of the parties involved will be subject to contract law and enforcement. (See Case Study: Data Sharing, New Zealand)

The information supply chain (Copy PIARC)

Data explosion is not an ITS phenomenon. It mirrors what is going on in social media, on the Internet, in marketing and other sectors. As a result, many countries have legislation and regulation governing how to data should be collected and handled. The ITS sector operates within these frameworks. As with all national legislation, they vary from country to country – but some broad and simple principles apply universally and should be taken into account by ITS practitioners even if there is no relevant legislation in place as yet.

The tension in this area is created by the basic question of who controls the data:

There is often anxiety amongst the general public (who are often data subjects) about what exactly is being recorded, how personalised it is, to what use it is being put, and for how long it will be stored. This concern is not always logical. For instance mobile telephone records and electronic banking systems create a comprehensive, maybe intrusive, data picture of individuals – but mobile phones and bank cards do not often receive the same level of criticism as the identification of vehicles through Automatic Number Plate Recognition (ANPR) (See ITS Technologies) for the purposes of:

The creation, use and storage of transport data – as with any other data – is a sensitive area and ITS practitioners should make sure they remain within the laws and regulations governing data processing in the country in which they operate.

It is sound practice to only collect what you need, restrict this to data actually required for the work to be done – and to discard the data once its purpose has been fulfilled. For example, for the purposes of calculating journey times – it is not necessary to record the names and dates of birth of drivers.

The Stockholm Congestion Tax back office permanently deletes all vehicles and journey data once the journey has been paid for or any dispute relating to the journey has been resolved. Since this office generates tax bills monthly, hardly any data is kept for longer than a month. This is an example of good practice. (See Case Study: Stockholm Congestion Tax)

Restricting types of data, encrypting data irreversibly, and having strict rules for data handling and storage, including time limitations, will keep an ITS application within the bounds of good data practice.

Data should only be personalised when it needs to be. Data collected for tolling (See Electronic Payment or Law Enforcement) purposes has to be personalised to be useable – but even with tolling this can be minimised. For example, the collection of personal data (such as exact trip location) for tolling can be minimised by using a “thick client” – where most of the transaction processing is done within the vehicle – reducing the amount of information sent to the back office to generate the toll charge. When collecting data to establish traffic flows (See Network Monitoring) or public transport usage loading (See Passenger Transport), the names and addresses of travellers are of no importance and should not be collected, even though the possibility exists.

It is a generally recognised principle that information should not be recorded just because it exists and can be recorded. It should only be recorded if it is needed for the process being carried out. For example, vehicle speed data collected on motorways to determine traffic flows – the licence or number-plate data would usually be encrypted in an irreversible way – so that all the data processor knows is that the same vehicle passed point A at x time and point B at y time. Even if the operator wished to reverse the encryption process and identify an individual vehicle, this is not possible.

Data should only be stored for as long as needed. “The to be forgotten” is a phrase sometimes used to express this. Once the process for which data was collected has been carried out – whether this is to generate a toll charge or to authorise a public transport passenger to undertake a journey – it should be discarded. If there is good reason to keep it – for instance, to carry out some kind of statistical analysis or forecasting – it should be irreversibly made anonymous before storage.

Data subjects should be able to check on the personal data held relating to them, and there should be a process for challenging – either the content of the data or the fact it is being stored at all.

Season tickets usually generate detailed personal data about the purchaser, such as their address, date of birth, bank details through their payment, and gender. Ticket use will generate detailed trip data linked to a person if the public transport (See Passenger Transport) system uses gates, readers or scanners such as the one illustrated in the figure below. Individual “paper” tickets, as a rule, would only generate data about the location of the purchase and the trip. It is good practice to offer anonymous ticketing and cash payment options whenever possible.

Figure 2: Smartcards for Public Transport Ticketing (Transport for London)

The movements of trains, buses and other forms of public transport are often controlled and/or monitored by ITS – and so, record data. This can lead to privacy (See Privacy) issues for drivers and other staff – and their representative bodies – such as driver associations or trade unions – voicing concerns. On the other hand, location applications can improve the safety of public transport staff.

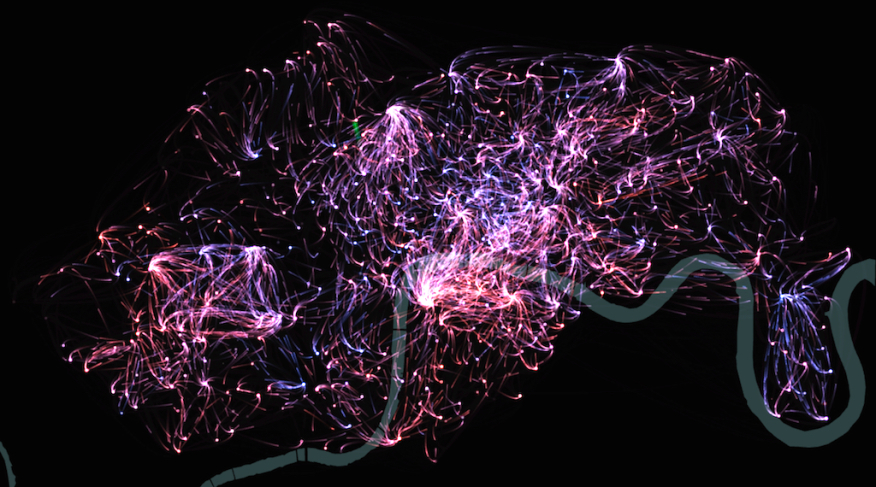

Data are generated through many different ITS traffic management systems in use (See Network Monitoring). Vehicles are identified and their location, direction of travel, and speed is recorded – both to enable optimal traffic management at the time, and for future modelling and forecasting. The figure below shows how data from London’s cycle hire scheme can be used to visualise cycle traffic movements. This type of data collection may be completely impersonal – such as loop detectors which only establish that a vehicle is there and the speed at which it is travelling. It is also capable, though, of detailed personalisation – if the vehicle is identified by ANPR and an image captured enables the identification of driver and passengers. Good practice is to only record the data needed for the job in hand, and to irreversibly encrypt or discard the rest.

London Cycle Hire Scheme – Visualising Cycle Movements (Illustration courtesy of City University London).

If an accurate tolling (See Electronic Payment) charge is to be levied, a lot of personalised data regarding the vehicle, its keeper, its location and possibly its exact trip details, and the customer’s bank details – have to be recorded. Good practice is to discard this after an agreed period – after which the driver no longer has a of challenge against the charge.

New ITS applications of driver support systems (See Driver Support), autonomous vehicles and cooperative systems need to be considered carefully before establishing good data handling practice. These systems rely on an enormous amount of location and trip data in order to be safe and effective. There is no reason, though, why this data should be kept and stored after completed trips without being made anonymous.

A fairly new area of ITS data is crowd-sourced data. Social media and technology – such as Bluetooth (See ITS Technologies) - offer the opportunity to generate or collect comprehensive and detailed travel data relating to individuals. This can either be with their active or implied consent – or without their knowledge. For instance, a keen user of social media who uses platforms such as Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn and TripIt to broadcast their whereabouts can be considered to be consenting to their travel profile being constructed. By contrast, logging the movements of somebody who has not realised that their phone has Bluetooth and that it is enabled – is at the other end of the scale and can be reasonably considered as an invasion of their privacy. They have not consented to their data being used and are not aware that they are generating data. In many countries, the fact that they are anonymous would still not make it acceptable to use their data.

Most ITS implementations generate, use and store quantities of data which are enormous by the standards of even only ten years ago. Much of this data is highly personalised and very sensitive. Many countries recognise, in law, the of individual citizens not to be excessively surveyed, monitored, recognised, and recorded.

Legislation to regulate data is cast to cover a variety of scenarios. It applies to drivers and passengers just as it does in other areas of life – such as voters and bank customers. Those handling ITS data (traffic control centre operators, electronic payment back-office operations, information service providers, for instance) will be subject to the regulations in place in their countries. Data collected and processed in a control room for instance, must be kept secure from unauthorised access and misuse. The principles behind data regulation should apply easily across sectors. ITS practitioners should bear in mind that digital camera images (such as images captured for traffic or payment enforcement) are classified as data.

Data Control Room (Copy ITS United Kingdom)

ITS practitioners processing data should have access to simple and clear codes of practice, drawn up by their employing organisations on the basis of advice from those with suitable legal expertise. These codes should ensure that national legislation is followed but also add a layer of good practice relating specifically related to ITS. Training and monitoring of staff is essential to ensure that any code of practice is understood and adhered to. It should form part of the management culture of all ITS workplaces where data is processed or stored.

One reason why people distrust the collection of data by – by and for – ITS systems is the suspicion that the principles of personal data protection are overlooked or deliberately ignored. For example, if a request is made by the police or security agencies for access to personal data on journeys and locations, will the ITS data owner provide it? Are there requirements in place that govern how police and security requests are handled?

There have been examples where location data from an ITS source has been used as evidence in civil and criminal proceedings to prove that a defendant was present at a specific location and at a specific time. There are also cases where the defence has challenged the legality of the data capture, its accuracy and even its use. If the data is inaccurate, should have been destroyed or made anonymous under data regulation legislation, it may be ruled as inadmissible.

The best way of keeping personal data secure is not to expose it to the risk of theft or misuse – by minimising and making it anonymous it wherever possible. Where sensitive data has to be kept, it is essential to ensure it is stored and handled in compliance with legal requirements and good practice.

There will almost certainly be national legislation affecting how personal data should be stored and kept safe. Complying with legislation alone though, is not likely to optimise data security. Expert advice should be sought from specialists or by retaining expert capability in-house. While external, malicious attacks from hackers aimed at financial gain or disruption are often seen as the most likely security risk, organisations should also be aware of the possibility of attacks from staff who may, for some reason, misuse or misappropriate data to which they legitimately have access at work. There are also potential risks from staff who are incompetent, unlucky, or badly supervised, and who can do as much damage as an external hacker without intending to.

Data security threats evolve and renew daily. The security regime in place must be designed to recognise this so that the defensive measures keep pace with threats.

Good practice in ITS data security can be summed up as:

The growth in the amount of data used and created by ITS and the increasing depth and coverage of this data – often personalised and with reference to time and location – make privacy considerations increasingly important in ITS. The capabilities for collecting and storing personal data are very well developed. For example, when using public transport the use of an electronic ticket and the deployment of CCTV cameras at stations, stops and on vehicles gives access to data such as a person’s name, address, date of birth, gender, bank details, place of work and other places regularly visited. The data may be combined with the use of software that recognises faces, a way of walking or other types of movement such as running.

A driver of a private vehicle may have a similar level of detail recorded about themselves and their vehicle – such as driver licensing and insurance arrangements, the payment of vehicle taxes, fees and tolls , and monitoring of the vehicle for traffic management purposes, parking enforcement or tolling.

There are a number of definitions of privacy from that offered by Google to Article 12 of the UN Declaration on Human Rights (1948):

“No one shall be subjected to arbitrary interference with his privacy, family, home or correspondence, nor to attacks upon his honour and reputation. Everyone has the to the protection of the law against such interference or attacks.”

Sensitivity to privacy varies greatly between countries and cultures and this is one area of ITS where local knowledge of, and understanding what is acceptable and what is necessary is necessary for each deployment. For example, in the UK the prevalence of closed-circuit television (CCTV) surveillance in towns and cities, buses and trains, means that the average Londoner appears in camera shot 300 times a day – the figure below provides an example. Some people find this unacceptable; others accept that being observed and even actively monitored is a consequence of travel in this day and age. One person’s privacy can be another person’s danger. CCTV monitoring of motorways (See Network Monitoring) may be regarded as a loss of privacy for drivers, but if the operator spots a “ghost driver” travelling along a motorway in the wrong direction, it can save lives.

Street scene in London showing CCTV camera above VMS for Olympic Games (copy ITS United Kingdom)

Camera technology provides the basis for many ITS application such as enforcement of traffic laws and electronic payment in tolling and ticketing. Vehicle licence plate recognition and facial recognition software depend on the capture of digital video images. Enforcement notices rely on camera images to identify the offending vehicle and – in some cases – the driver. A photograph of the whole front of the vehicle may remove any doubt about who was driving the vehicle at the time of the offence but in some countries this is considered an unacceptable intrusion.

One general principle is that privacy can be traded for benefits – such as correct fares or safety. The technology allows the traveller to be charged the amount to use public transport, and may increase personal safety or ensure that traffic information provided is relevant. If the intrusion into the individual’s privacy is seen as benign and fair, public concerns are also lessened. For example, in the event of a serious road accident, eCall (the European Union’s collision notification system) automatically initiates a 112 emergency call from an in-vehicle device to the nearest emergency centre with details of the vehicle’s precise location. (See Driver Support)

Another principle concerns the storage of information. Digital images and other personalised data (for example details of a journey or a transaction) may be stored and held in a computer’s cache memory for the benefit of the police, road authority or transport operator – but the individual may not benefit from this directly. Good practice requires that data is made anonymous or reduced (by discarding the data elements not needed for a specific purpose) and eventually deleted (by setting a sensible deadline in terms of the purpose of use, after which the data will be destroyed).

The practice of making data anonymous may to help to allay suspicions about potential misuse and concerns about data security, criminality and identity theft. Payment transactions that involve details of credit card accounts are especially vulnerable. For instance, when a person passes through a ticket-operated barrier to use public transport it is not necessary for the operator to know the name of the user or their credit card details – only that the ticket is valid. Once this has been recorded, all personal data relating to the ticket holder can be discarded – retaining only data that is essential information for transport management purposes, such as trip origin, destination, fare paid and timing.

As camera and other sensing technology become more sophisticated, privacy will increasingly be at risk. Undertaking a proper impact assessment of privacy issues for each camera deployment can mitigate the risk. Any formal or informal assessment of risks to privacy must take account of national laws, regulations or codes of practice and factor in variables such as what may be acceptable to data subjects, what is socially desirable (for example for law enforcement or road safety) or commercially attractive such as a product loyalty card. Proper consideration of privacy issues must be based on reaching a consensus on the acceptable balance between loss of privacy and the achievement of objectives – such as seamless journeys.

During recent years, the concept of Open Data has been widely promoted in Europe and North America. The basic principle is that if the data has been collected at public expense, it should be made available to anyone to use. This policy has been adopted by governments in the interests of transparency and accountability and to stimulate innovation and the development of added-value services and products. In Europe, the EU is a strong supporter of Open Data as a principle, and similar trends can be seen elsewhere in the world. Open Data is a concept, which particularly applies (but not exclusively) to public sector information. The transport sector includes major datasets owned by the transport industry in the public and private sectors (datasets such as timetables and real-time running information). To deliver a comprehensive open data policy for transport, these bodies need to come together to support the agenda.

An open data policy raises many challenges – such as privacy and personal data, commercial confidentiality, data quality and accuracy, and – not least – the cost of making data available. Many public sector data owners across the world have developed workable solutions for dealing with these. This includes making anonymous or removing personal data and implementing policies on charging for re-use of data in line with local/national policy or practice.

In 2012 it became UK government policy for each government department to publish an Open Data Strategy setting out what data sets it would make available over the next two years, and how it would stimulate a market for its use. A UK Open Government Licence has been developed to provide a common set of terms and conditions on the provision and use of public sector information. Government-owned datasets can increasingly be accessed from a “data warehouse” that is being developed into a National Information Infrastructure so that the most critical government data can easily be sourced from one place. (See: http://data.gov.uk )

The Department of Transport’s Open Data Strategy outlines the principles behind its data collection, management and release policies, and lists available data sets. These include core reference datasets (also known as “big data”) – that cover definitions of transport networks, timetables/traffic figures, planned/unplanned disruptions and performance figures. The strategy also signposts potential users to the type of licence needed to re-use the data. (See http://data.gov.uk/library/department-transport-open-data-strategy-refresh).

Intelligent Transport Systems are a “data-rich” and reliant on data and information. ITS needs data to operate, it creates data as it operates, and retains data after operations are complete. It includes data about transport networks (such as roads) and data about transport movements on the network (traffic counts, bus timetables, passengers and freight).

There is strong public interest in transport information – which can be used to inform travel choices, to improve performance and to hold operators and Government to account. Many organisations or individuals, other than the original data owner, can see value in the data – to create services or undertake research – for both commercial and non-commercial purposes. For them, a “data warehouse” provide a wealth of information. An example is Transport for London’s , London Datastore website, which provides access to large data holdings about London – as the figure below, showing its homepage, illustrates. (See Case Study: Open Data UK)

London Datastore (Source – homepage of http://data.london.gov.uk/)

It is widely accepted that the data owner should not be expected to carry out a lot of work or incur a lot of expense to process the data to make it is more useful to those who wish to use it under Open Data arrangements. The data owner’s duty is usually limited to making the data available in its original state, when it was collected or used. The data owner may make its data holdings accessible through a dedicated website or by providing contact details for requests and may charge the data re-user for access to recover the cost of making data available.

Data owners often require those accessing the data to provide basic details of who they are and their intended purpose of use (to prevent inappropriate use). It has also become common for the original data owner to require data re-users to accept liability (See Liability) for any damage or loss sustained as a result of the service or product they create using the data. This may be achieved through a simple disclaimer tied to the accessing of the data. It is essential that no personal data is made available without being made anonymous.

The principles behind access to Open Data in ITS are gaining ground, and major users of data for ITS applications and services – such as Google and TomTom – see value in more and more countries adopting the policy.

Once a decision has been taken to embrace the Open Data concept, simple principles of good practice should be followed: