The development of an ITS Strategy or Framework Plan needs to bring together the main stakeholders and agencies involved in deploying future ITS systems and services. To win their support, it is helpful to have clear vision of how ITS should develop. ITS needs technical and political champions who will generate support for the vision. Whoever champions the realisation of that vision will need advice to fulfil their informed customer role in the face of rapidly changing technological capabilities.

Mature, integrated ITS services and service markets are something that evolves over a period of time. Countries, regions, and cities can lay the foundations by developing a strategic framework and a common plan to provide direction to ITS deployments locally - or by organisation. A national, regional or local ITS policy framework provides an opportunity to analyse the requirements for deploying ITS, and to assign roles and responsibilities, budgets and priorities. It should reflect the market, policy and political perspectives as the context for the deployment.

A policy and coordination framework is aimed at coordinating the actions of the lead actors on the basis of a mutually-agreed vision of the future. To guarantee buy-in by all the stakeholder groups, the planning process must involve the representatives of those groups. Examples of ITS deployment strategies developed in a multi-stakeholder cooperation include the US ITS Strategic Plan (See the U.S. ITS Strategic Plan) from 2009 and its planning workshops (See ITS planning workshops), the EU ITS Action Plan from 2009 (See EU ITS Action Plan) and the Finnish ITS Strategy from 2013. (See Finnish ITS Strategy)

A well-developed ITS Framework will provide the basis for specifying ITS system architecture and for considering the ways in which individual ITS systems can be integrated. The deployment path is likely to be a set of upgrades or improvements to existing systems and services - as well as deployment of completely new systems and services. Prudent ITS implementation will be based on an evolutionary strategy that begins with small steps whilst keeping the future big picture in mind and maintaining at all times the provision of services under improvement. By choosing "early winners" - initial deployments that are relatively small and have a high probability of early success - it will be possible to show the efficiency and effectiveness of ITS investments early on to ensure the continuing interest and support of key stakeholders.

The ITS strategy should also consider the role of private, commercial ITS services as well as public ITS services. The benefits of inter-agency and inter-jurisdictional discussions, negotiations, and agreements should also be analysed.

In developing the ITS strategy and policy framework, it is advisable to establish today's situation - as a quantified baseline for future evaluation. To be meaningful, the progress of the plan needs to be assessed periodicly - around every 3-5 years. Priorities should be based on the results of evaluations of ITS deployments as well as the results of research, development, pilot projects and field operational tests (See Project Appraisal and Monitoring and Evaluation). A good example of a local ITS strategy is provided by Seattle in the USA. (See Seattle ITS Strategic Plan 2010-2020 and Strategic ITS Plan)

The process of developing an ITS Strategy or Framework Plan with multi-stakeholder cooperation contains a number of steps, which are described below.

The starting point is to determine the major transport issues which ITS should address. Ideally, this will be based on a survey of the needs of users: shippers, carriers, distribution companies, bus and coach operators, commercial bodies, private individuals, and national and regional governmental organisations. The Framework needs to respond to current policy issues such as environmental sustainability, economic development, safety and security. A good example of such an analyses is the European Commission's Urban Mobility package from 2013.

The aim of a needs-driven Framework plan should be to define the basic supporting infrastructure for ITS - using existing services, projects and infrastructure as a springboard where possible. Existing services and projects that use ITS technology should be identified and brought within the scope of the plan. The Framework needs to be developed through discussion, consultation and meetings with the major stakeholders - and augmented, if appropriate, by dialogue with key decision makers and politicians. The work can include mapping of transport problems to ITS user services. (See Benefits of ITS) ITS functions - or user services - relevant to industrial and regional needs should also be identified and prioritised.

An important input to the ITS Framework Plan is developing an inventory of existing ITS systems and services - that are either already operating or under development. This step follows on naturally from the analysis of stakeholders. For example, some of the road authorities and operators may already be operating freeway management, incident detection and management, or traffic signal control. They might add to these public transport management, emergency management, and advanced information systems in the pipeline. The future of these (what will become “legacy systems”) must be addressed specifically in the ITS Framework Plan. Decisions will be needed on whether to retain and upgrade them or to invest in new systems that have improved capabilities and performance. Decisions to terminate some services or to scrap some systems may also be taken in favour of purchasing better services from the ITS service market or using more cost-efficient technology solutions.

It is likely that a number of different organisations will need to ‘buy in’ to the overall vision for ITS and the implementation process to make the vision a reality. Harmonising the positions of the principal stakeholders is probably the most important aspect for the deployment and operation of ITS. The successful development of new services will be much easier if stakeholder's individual motivations and interests can be aligned. Close contact with the key actors is needed throughout the planning and deployment process.

The list of organisations which might be involved can be extensive but only a few will play a leading role. The ITS service providers will naturally need to be involved. Almost certainly the list will need to include the agencies involved in operating the major highways, the local authorities responsible for the main arterial roads and local roads, the traffic police and other traffic management agencies. Depending on the specific ITS application, the operators of commercial vehicles, public transport operators, and the motoring organisations representing private motorists, may also need to be involved.

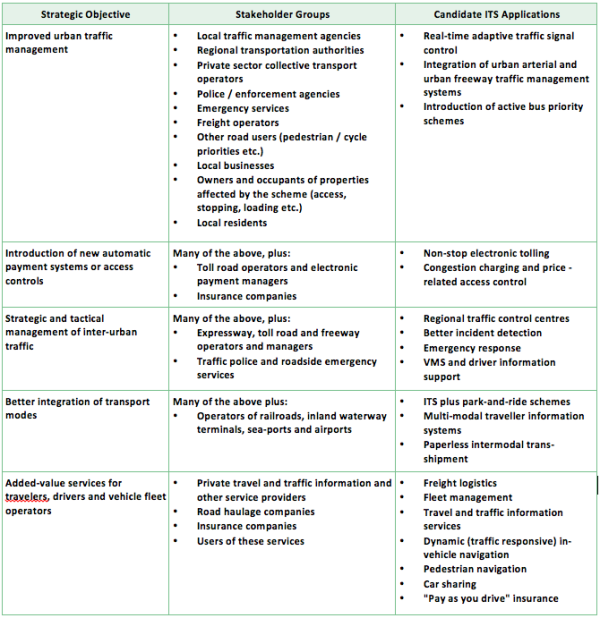

Experience shows that ITS services involve an increasing number of organisations as the full potential of the new technologies is realised. The table below illustrates this point with examples of the more common objectives for investing in ITS - showing the varying degrees of complexity and stakeholder groups. Senior officials of public agencies and chief executives of private sector companies will often be involved in the definition of the ITS Framework Plan - because of the level of commitment that is required to make the plans become a reality.

The body of stakeholders which will need to be consulted during the decision-making process depends on the local situation and the issues at hand. It is important to be aware and sensitive to potential issues at all times - in what may be an evolving situation - as ITS services develop. Even apparent minor stakeholders can introduce issues which must be recognised and dealt with. Generally it is better to uncover and address any issues early on in the planning stages, so proper adjustments can be made. An effective communication strategy with the stakeholders provides the opportunity to develop contingency options.

Figure 2. Examples of Stakeholders for ITS Projects

If the consultations and preparation work has been done effectively the ITS Framework Plan will be supported by all the leading actors. For deployment to proceed, their awareness of ITS, and expectations of it, must be compatible. Focusing on ITS services as a whole, will enable identification of those services and enabling systems with a broad context - which will require support from a strategic ITS framework. The architecture may need to support localised services such as common infrastructure used by ITS - for example communications networks, data exchange protocols, electronic payment services, where economies of scale and standards are required for economic viability.

The issue of multiple organisations, data and information exchange needs to be addressed both psychologically and institutionally. In day-to-day operations, protection of jurisdictional authorities and responsibilities is one of the most common problems encountered when integrating regional traffic control. Organisational culture conflicts need to be resolved in ITS public-private partnerships. Each of the multiple organisations involved has its own history and standard operating procedures that can make it difficult to build the necessary partnerships. While group decision theory (based on the concept of win-win solutions) may apply reasonably well to these situations, game theory (based on minimum-maximum principles which evaluate strategies under worst-case scenarios) may be more relevant to handle newer ITS applications - such as combatting or alleviating the impact of terrorist or cyber attacks.

The promoters of ITS services or projects need to consider the following:

Experience shows that it is helpful for the key actors to agree:

The ITS Strategy or Framework Plan should be published alongside a set of documents which will describe the proposals and provide a basis for agreement between all the stakeholders. These documents will together provide the basis for further refinement and consensus building during the subsequent stages of ITS deployment. Together they will provide a comprehensive statement of the ITS policies and priorities and what is to be achieved.

Examples of the type of documents which should be published are:

ITS services are the result of specific value chains varying according to the specific service - but with the same basic functionalities. The figure below presents a generic value chain for travel and traffic information services - but it applies to most ITS services. Each of the functions in the value chain specifies a responsibility for carrying out a specific task - and that responsibility is assigned to one or more of the organisations involved.

Traffic information service value chain by TISA Lohoff, Jan 2013.TISA WG Quality: Quality criteria and methods. Presentation at the European ITS Platform WP 3.2 and 3.3 Kick-Off Meeting. Brussels, 27 November 2013.

The roles of road authorities and other public sector stakeholders differs depending on the ITS service in question. Typically, road authorities have a more prominent role in services related to their core business of network operations, such as freeway management, traffic management, and incident management. They do not, though, have any major role in most vehicle based systems - such as driver support systems. In addition to the roles in the value chain, the public sector is always responsible as the regulator for any regulations or legislation setting out the legal framework for ITS service provision.

The roles of different stakeholders - and the borderline between public and private stakeholders - varies depending on national organitaional cultures and traditions. In some countries, the public sector stakeholders have responsibility for most parts of the value chain - such as real-time traffic event information services - whereas in other countries, the public sector is only involved in providing data for these services.

There is no single correct model of division of responsibilities for ITS services. Each ITS service has its own value chain or network, and the roles and responsibilities are determined by the local organisational cultures, tradition, conditions, markets and economic situation. Sometimes, the public sector needs to take a more active role than expected - such as when the private sector will not, by itslef, provide a socio-economically beneficial ITS service in areas of the public sector's jurisdiction.

ITS covers a wide range of systems and services. Different stakeholders are involved - and their roles and attitudes, as well as legal and institutional issues - vary in each ITS deployment. Whilst there will be wide variations between different applications and individual institutions - three broad groups of stakeholders investing in ITS can be distinguished:

1) Users and consumers of ITS (corporate or individual): require systems and services that meet their real needs. They have high expectations of service quality, reliability and availability (dissemination channels). The willingness to pay for ITS systems and services strongly depends on the actual and perceived utility of the service as well as on its image. The acceptable price may not correspond to the actual costs of service generation and delivery

2) The public sector: will adopt ITS to deliver various public services, objectives and strategies. Where these are made explicit - public interests in ITS service development are usually justified by positive impacts on traffic management and modal shift, road safety, sustainability, economic development, business location, image and social inclusion. Public authorities then seek to involve the private sector so as to mobilise the enterprise culture, limit public expenditures and increase efficiency

3) The private sector: share the objectives of marketing their products/services through ITS, entering a future growth market - and/or developing a new profitable business area. In this, the private sector depends heavily on the framework conditions established by the public sector - which they soemtimes perceive as an obstacle to the free market. On the other hand, differences between various private sector stakeholders leads to different orientations and priorities when defining new ITS service delivery models. These differences need to be recognised in the strategic agreements with the public sector.

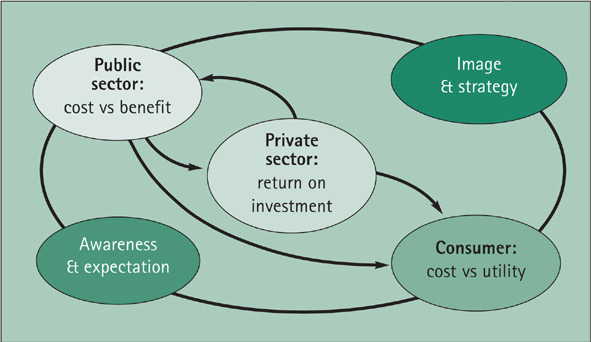

Three very different business model evaluation systems come into play - as these groups consider whether to allocate their budgets to ITS.

1) The consumer (any individual or organisation that is the end user of an ITS system or service) evaluates the utility of ITS in relation to the buy-in cost and any recurring fees and charges that have to be aid.

2) The public sector usually has to justify investment in ITS on the basis of public service criteria or the benefits to the community - including affordability of the initial capital spend and any maintenance and long-term operating costs. There are several alternative evaluation methods (See Project Appraisal and Monitoring and Evaluation).

3) The private sector is concerned with the forecast return on the investment needed to bring ITS equipment, products and services to market - and the extent and reliability of any revenue streams

The interactions between these very different requirements are shown schematically below. ITS projects will frequently require justification against at least two, if not all three of the underlying business models. Failure to meet one or other of the investment tests will produce a classic “chicken and egg situation” – who goes first, the supplier or the purchaser in making a commitment to the system or product? Experience shows that this dilemma has been resolved in countries like USA and Japan by the public and private sectors jointly developing a strategic plan - including an ITS architecture that clearly defines the institutional responsibilities. When starting up cooperative system deployment in Europe - the Amsterdam group (See Amsterdam Group) consisting of vehicle manufacturers, road authorities, cities and private road operators - agreed on a road map with specific milestones reinforced by a common Letter of Intent signed by all, and a dedicated Memoranda of Understanding between the relevant local, regional and national stakeholders involved in different local deployments.

Interdependencies between the public sector and consumers.