Road Network Operations

& Intelligent Transport Systems

A guide for practitioners!

Road Network Operations

& Intelligent Transport Systems

A guide for practitioners!

The “user friendliness” of the road network depends on a complex interaction between the technical systems – such as traveller information, route guidance and traffic control – and the road network users. Ultimately, people are individuals and will make their own decisions, but there are many theories and models that can help us to understand individual motivation and the effect this has on behaviour.

By taking account of human motivation and decision making, Road Network Operators should be better placed to understand how people behave both individually and in groups – and how best to influence that behaviour in order to manage the road network.

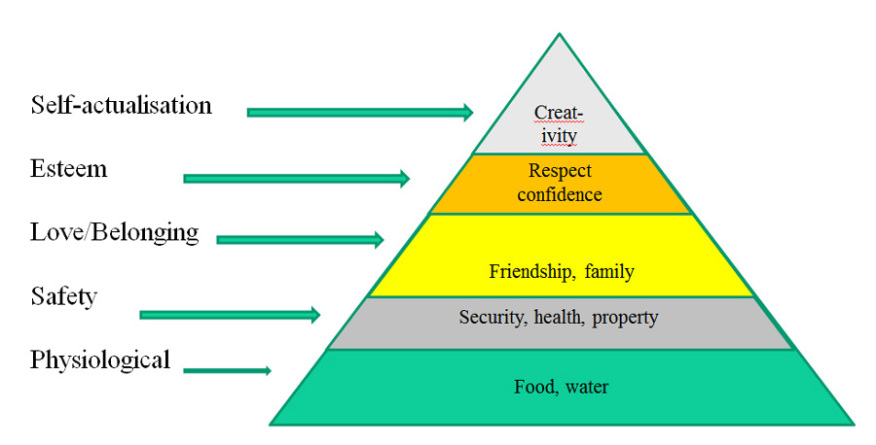

The psychologist, Maslow proposed that humans have needs that influence their behaviour, which can be arranged in a hierarchy. Once a need is satisfied, then behaviour is influence by the next (unsatisfied) need in the hierarchy. The most basic are physiological needs (such as food and sleep). Once these are satisfied, safety needs take over and so on.

Expectancy theory says that choice or behaviour is motivated by the desirability of outcomes. In general people prefer to avoid negative consequences more than increase positive consequences – for example, to arrive at 08.45am for a 9.00am appointment is of minimal benefit but arriving late may be of considerable dis-benefit.

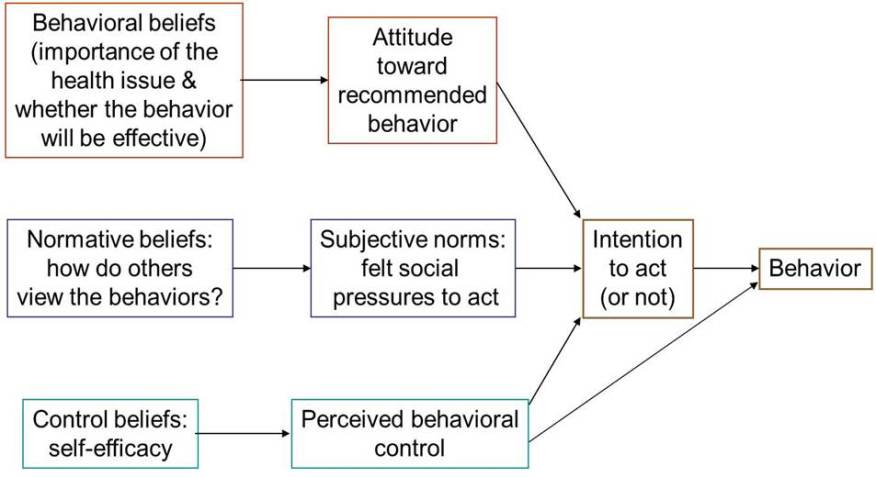

According to the theory of planned behaviour, an intention to behave in a certain way is influenced by three things: the expected outcome (positive or negative), how others will perceive the behaviour and a judgement about one’s capability to carry out the behaviour. It seems that there are “boundaries” within which people feel they can and should act and areas where they feel they cannot. In part, this depends on having “permission” to act in a certain way – whether this is permission one gives oneself or whether it is permission granted by others. For example peer pressure can have a profound effect on young male drivers’ behaviour and their willingness to comply with traffic laws.

Incentives and positive reinforcement make a behaviour more likely in the future. Benefits that appear certain and immediate are generally preferred to those that are less certain and more distant. This is called the saliency of benefit.

People have an innate drive to be self-determined – they mostly prefer to be in control and will seek information in order to make decisions. This can be used to advantage in Road Network Operations by providing advice to road users and other travellers. Their trust in information (its credibility to them) depends on many factors including:

In general, people have a poor appreciation of risk (consequences and probabilities), and especially of very small risks. Events that can be more easily brought to mind or imagined are judged to be more likely than events that cannot easily be imagined. This is called the availability bias. Press reports, for example, tend to favour Bad News stories, which promote negative expectations. The managers of Traffic Control Centre operations will be acutely aware of this.

People do not always make choices that are in their best long-term interest. Sometimes “wants” are satisfied before “needs”. So, people are not always economically rational even when all necessary and consistent information is presented. The road users’ response to information messages may differ from what is intended by the Road Operator.

Few individuals constantly seek new experiences. For most there is a tendency to keep doing things in the same way. This is called inertia (an analogy to mechanics). So, people either do not undertake some new activity or continue to do the activity in the same way. To a large extent, these habits are a coping mechanism for the plethora of choices in everyday life.

Decision making also depends on the user’s willingness to seek out all required information (if it is even available). So, a typical approach in many situations is “satisficing” - seeking solutions that are not necessarily optimal but are “good enough”.

One theory proposes that people aim to reduce dissonance (degree of discomfort) between their view of the world and their actions. This can lead to “post-hoc” (after the event) justification of a decision made.

Related to this is a tendency for people to display confirmation bias – a tendency to seek out information (and to preferentially trust that information) that confirms an existing belief, rather than new evidence that may contradict that belief.

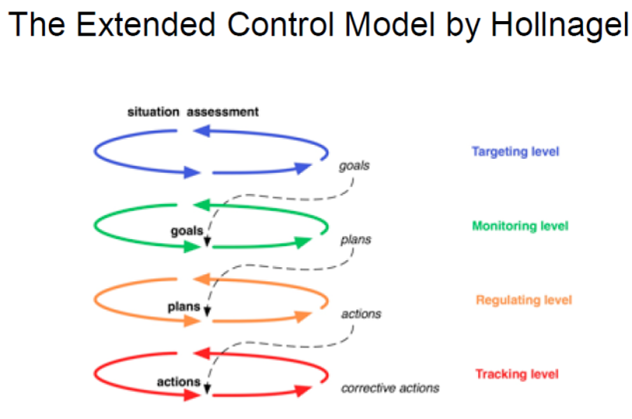

In the driving context, Intelligent Transport Systems (ITS) can provide information and assistance to drivers and can play a part in their decision making. Research has led to various models – one model describes driving decisions at three levels:

An extension to this model considers driving decisions at four levels with feedback and interaction between them.

Individual drivers exhibit a range of driving behaviour and styles of driving. Driving can also be considered as a social activity. Interactions between vehicles and between vehicles and other road users are largely interactions between people. An aggressive driving style, particularly in a cooperative driving culture, may be highly offensive. The term “road rage” has been coined to describe extreme feelings or behaviours aggravated by, for example, other road users’ behaviour or driving situations such as congestion.

ITS can provide much helpful information and assistance to drivers. It can also introduce potential problems. Attention to in-vehicle information and communication systems can detract from driving performance and decision making. Although ITS can provide assistance to reduce the drivers’ workload, it is known from research that a sustained low workload (underload) can lead to boredom, loss of situation awareness and reduced alertness. It has been observed that the greater the number of support-system functions which have become available through ITS, the higher the risk of drivers losing competence, which can sometimes be combined with their reliance on ITS functionalities. (See Driver Support)

Road users typically believe they have an implicit contract with the road network operator. This (in their mind) might include keeping the traffic flowing, maintaining the cycleway, and providing safe and adequate public transport. As a minimum, road users’ basic needs should be considered – such as food and toilet facilities and rest stops for longer journeys.

Anger and frustration can arise if the service quality falls below road users’ expectations. ITS can help to manage expectation – for example by providing information about service quality and frequency. This information needs to be available to road users before their journey (for example on the internet, or printed information), and during their journey (for example on signs, notices, mobile devices). ITS, and communication channels more generally, might also be employed to counteract “Bad Press” stories about the road network.

Road users develop habitual behaviours, partly to reduce overload and anxiety about unknown situations. This “learned behaviour” leads to an expectation of permanence and consistency – so if something changes there can be surprise, anger and frustration. ITS, if well designed, can be very helpful in reducing these negative emotions and provide information likely to influence behaviour. (See Traveller Services)

Road closures and changes to schedules should be made available through both ITS and conventional means well in advance, if possible, using multiple information delivery mechanisms.

ITS is particularly useful for providing real-time information about maintenance activities and disruptions to service levels such as traffic congestion. Road users can become anxious and frustrated if they do not have any scope to affect their situation – or if no information is provided (such as the reason for the delay, how long it will be, and what the alternatives are).

ITS information can provide additional confirmation of the situation, sufficient to nudge behavioural change. It should be presented in a clear and authoritative manner. The information should be consistent with other information (unless it is newer and better than existing information).

Apart from a sole road user on an open road, most road use occurs in the context of other road users and so can be considered as a group activity. Social psychology and game theory, involving cooperation and competition, provide useful insights which may be of value to the road operator:

It is noticeable that there are different driving styles in different countries (for example, more or less-aggressive driving, queuing practice and turn-taking, use of mobile phones). Again, ITS can be used to rapidly contain situations or reinforce positive behaviour so that it becomes normalised.